Delusions of the Grandeur of Belonging: Jews in Pre-Holocaust Europe

by Norman Simms (November 2017)

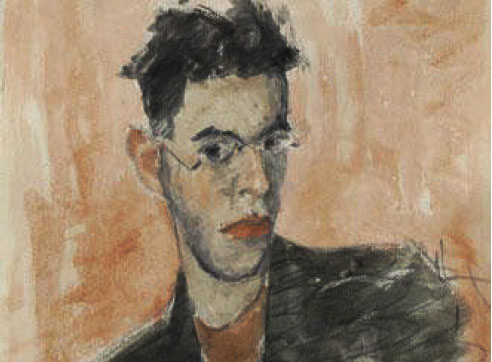

Self portrait, Peter Kien, Theresienstadt Museum

Yet Jewish tradition also invites us to consider complexities in the nature of

truth. Truth depends on context, and it is, at times, subservient to other values.[1]

Even when authors write books about important Jewish intellectuals and artists, what is often neglected, if mentioned at all, is the way in which Jews and Judaism exist in the world, that is, in the consciousness and unconsciousness of the cultures that form the context to Jewish existence. Most people who write, review, and read such historical books consider Jewishness to be a kind of incidental matter,[2] particularly when the subjects were themselves not very concerned or educated about their own Jewish identities,[3] sometimes to the point of outright denial. And if they do touch on the matter, contemporary authors tend to operate out of a mindset shaped by presuppositions: models that are at best irrelevant to, and at worst distortive of, the formative experiences and personalities created in opposition to an environment Jews in the past two centuries assumed to be secular, tolerant and just. Even more than that, these historians and sociologists seem to deal with of a sense of Judaism that they treat as equal to late twentieth-century (and all too often North American) Ashkenazi practice—in other words, religious according to post-World War Two’s Orthodoxy, Conservatism and Reform paradigms of Jewishness, and a folklore vision of ghettoes, shtetls and parents awkwardly assimilated into Western communities.

However, for nineteenth-century Jews in France and in German-speaking lands who believed they had transitioned into successful novelists or essay writers, artists and art historians, academics and museum directors, medical professional and scientists and other intellectuals, the situation was quite different. The limited civil rights granted by Napoleonic decrees and the political Emancipation partly gained in some Central European states could not be assumed to be permanent and open to further consolidation, welcome as these advances were.

To begin with, to achieve any degree of assimilation, Jewish individuals had to break away from their own family upbringing, slough off prior notions of religiosity, and reshape their personalities, all psychological processes about which they were not always very aware and that required much of what we would now call painful suppression of essential character traits inherited and formed by child rearing practices in effect long before they were fully socialized, before they were aware of their own feelings and logic, and before they acquired the language of the culture around them, and certainly before they could see and understand the hostility that impinged on their careers and private affairs. In moments of crisis, to be sure—such as during the Dreyfus Affair or the early manifestations of nationalist racism that would be full-blown in Communist, Fascist and National Socialist ideologies—some Jewish actors, journalists, art collectors and doctors sensed the danger; but usually felt they could avoid the consequences by ignoring the problem or asserting vigorously their own loyalty to the national states they lived in. Usually, too, they did not see any connection between what they were—Jews whom other non-Jews around them had no trouble in identifying, whether or they acted in a discriminatory manner—so that often, though not always, these same men and women did not take strategic steps to protect themselves or their reputations. Many of them optimistically (and tragically) considered their Jewishness incidental to whom they really were and what they actually produced as members of the cultural elite where they lived. Whether they actually converted (like Arthur Meyer, the editor of a conservative newspaper) or remained discreetly silent about their origins while wrestling with the problem internally (like the essayist and journalist Marcel Schwob) or awakened too late to the need to protest openly against anti-Semitism amongst their intellectual colleagues (like André Suarès), it was (as the saying goes) too little and too late. Or as Jonathan Sacks, former Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom, puts it:

“Become like us,” went the liberal argument, “and we will treat you like us.” But the invitation was fatefully deceptive, and the more Jews tried to be like everyone else, the more they were reminded that they were different. What others simply were, Jews laboured to become, and the harder they tried the more conspicuously they failed.[4]

Not all these nineteenth-century Jewish intellectuals and artists were contemporaries or knew—or knew about—each other, but when we begin the process I call midrashing, that is, to break up the textual coherence and continuity in their lives and writings, to focus on small details, inadvertent remarks, records of dreams and idle speculations—and to twist these new threads of word and image around one another: then something strange (or as Freud says: uncanny) happens. There emerges a different sort of pattern of coherence and continuity, as though something wells up out of their deepest shared cultural memories. Their lives begin to inadvertently recapitulate certain Talmudic typologies; and if they try to push back or escape from what seems to them constraints and stumbling blocks, the connections become clearer and more insistent.[5] The new configurations are recognizable, however, as arising from sources further back than most people can remember or imagine. This reminds us of what one of Rabbi Israel Chait’s students says as a note to his recent close-reading of Ecclesiastes (Koholet):

Rabbi Chait explained that King Solomon employed contradictions in order to keep the ideas hidden for the wise men to discern. Perhaps the use of apparent contradictions is the King’s method of enabling discernment. Mere facts do not engage the mind.[6]

Aby Warburg, the great art historian, saw this series of processes as following a trajectory from traumatic event to ephemeral and often somatic memories to collective attempts to create shared stories public images and transformative rituals (Pathosformeln or pathos-laden icons) and then on to a culturally-sanctioned series of renewals and repetitions (the Nachleben or afterlife of the codified triggers and soothing myths), leaving a fascinating but also uncomfortable and not transparent series of aesthetic artefacts, visual and verbal iterations, and gestural stimulants to further intellectual exploration.

For the Jews of France, until large numbers of immigrants from the Eastern Yiddish-speaking lands began to arrive in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the cultural base was Sephardic, especially in the south along the Mediterranean coast, mixed with Italianate families around Avignon. After the Great Expulsion from Castille in 1492 and the forced conversion and escape from Portugal a few years later, many of these Sephardim arrived as nominal Christians, conversos more or less sincere in their new religious affiliation.[7] For those who maintained a secret commitment to Judaism—both as Crypto-Jews and Marranos[8]—they formed new communities of their own, although the coastal towns like Perpignan and Montpellier remained under the aegis of the older Sephardi culture, strongly mystical followers of Nachmanides and the creators of Kabbalah (medieval Jewish spirituality and mysticism). Maimonidean rationalism (Aristotelian logic filtered through Arabic translations) was also evident in some groups. Early in the nineteenth century, Jews who belonged to Haskallah movement or the Enlightened values of Moses Mendelsohn arrived from German states, and from these middle-class and professional families arose quite a few of the social, cultural and intellectual leaders of the age. After the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, when Alsace and a large part of Lorraine were absorbed into the new German Empire (The Second Reich), many Jews chose to emigrate to France rather than accept Prussian hegemony. It was with French culture they identified and had come to esteem as the essence of Western Civilization—despite their own background in Yiddish language and religious practice. Fewer Jews came from Vienna and other cities in the Austro-Hungarian Hapsburg Empire.[9] Many Alsatians had family and commercial ties with northern Italy and the Mediterranean region now in France but then still part of Italian culture, such as the ancestors and siblings of Alfred Dreyfus.

Unlike the Yiddishkeyt familiar to American Jews,[10] Sephardic, Italianate and other Mediterranean (that is, the old notion of a Hellenistic and Levantine civilization) culture has always been more open to surrounding societies, particularly in regard, to science, philosophy and the arts. Cities such as Amsterdam, Livorno and Salonika, where their culture flourished, were highly cosmopolitan centres. Both the glorious metropolis of Vienna or the tiny river port of Roštok, in Bulgaria, as Elias Canetti, the Novel Prize winning author, reminds us was multi-lingual, and Sephardim, like his grandfather, could speak close to twenty languages as he plied his commercial trade up and down the Danube.[11] These urban centres were not the setting for variations on Fiddler on the Roof or I Remember Mamma. Yet in these places Jews flourished, at least before the Holocaust.[12] They had their own newspapers, art galleries, schools, professional associations and other markers of a distinct culture. Unfortunately, their willingness to live and work and sometimes think like the goyim (the non-Jewish nations) did not help them survive either; during the Holocaust, when push came to shove, most of their neighbours and colleagues betrayed them. To say this might be happening again right now requires an argument beyond the scope of this little essay, including its pesky and provocative footnotes.

[1] Amy Eiklberg, “When God Lies” Sh’ma Now: A Journal of Jewish Sensiblities (2 October 2017) hosted by The Forward online at http://forward.com/shma-now/truth/ 383935/when-god-lies/?utm_content=daily_Newsletter_MainList_Title_OPosition-1&utm_ source=Sailthru&utm

[2] In reaction against the notion of Orientalism, I have written many times about the phenomenon of Incidentalism, whereby the Jewish presence in the arts, music, science, medicine and so forth is treated as incidental to what is real and important. Without arguing in a essentialist manner (with all its racist concomitants) my studies try to place Judaism and Jewish identity as integral to European history.

[3] This might be, when practices by the non-Jew are included, taken as a type of asemitism, which Shimon Markish in Erasmus and the Jews defines as “a form of practiced indifference,” which at best can lead to an “open-ended, multivalent approach to Jews’ but more often is a wilful blindness or just another snobbish brand of incidentalism. See Kimberlee Cloutier-Blazzard, review of Debra Higgs Strickland, The Epiphany of Hieronymous Bosch: Imagining Antichrist and the Other from the Middle Ages to the Reformation (Turnbout: Brepols Publishers, 2016) H-Low-Countries. H-Net Reviews (August 2017) online at https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=50337.

[4] Jonathan Sacks, Radical Then, Radical Now: On Being Jewish (London and New York : Continuum, 2000) p. 186.

[5] Menachim Fisch, “Ambivalence as a Jewish Value: A ‘disease of the mind’ or a blessing, a ‘moment of paralyzing indecision that enables […] the impossible and expresses rationality at its utmost? How the Judaic tradition of criticism of norms creates ‘rational rabbis’ but also leaves us lost for words” Tablet Magazine (27 September 2017) online at http://www.tabletmag.co,/jewish-arts-and-culture/245849/ambivalence-as-a-jewish-value ?utm_soruce=tabletmagazinelist&utm_campaign=d19b

[6] Rabbi Israel Chait, Koholes: Man’s Quest for Happiness and its Inextricable Tie with the Inescapable Frustrations of Ambition (Yeshiva B’nei Torah, 2017) p. 41.

[7] Norman Simms, Masks in the Mirror: Marranism in Jewish Experience (New York: Peter Lang, 2005).

[8] Sometimes all these terms are treated as synonyms and cast as specific historical types; but my books have tried to distinguish between the general terms converso and New Christian (which contrary to Catholic doctrine persisted through generations, indicating that baptism did not change the essence of the body or soul—hence too the notion that converted Jews maintained their impure blood over hundreds of years) and the other categories which have nuanced significance: thus anousim (those who were violated or raped) were forced to the baptismal font, Crypto-Jews (who attempted to hide their private Jewishness under a mask of Christian practice) and Marranos (a pejorative term meaning pigs, whores and filthy creatures used by both their Catholic neighbours and communities of Jews who had escaped from the Lands of Perdition under the control of the Inquisition and repented, returned to Judaism and despised those of their brethren who did not have the courage or will to abandon the imposed faith). However, Marrano also came to mean people who were either confused, ignorant or indifferent to this pretence of being New Christians, and who individually or as families and sometimes whole communities moved back and forth; as Max Nordau and other Jewish observers late in the nineteenth century observed, they were what most Westernized Jews had become, neither one thing nor another; and these were the persons shocked and trapped when racial laws stripped them of their citizenship, ejected them from their professions, and sent them back “where they belonged” where, having no humanity left, they were slaughtered like beasts.

[9] One must recall that for a long time Vienna was the capital of an Empire that included Spain and her possessions in Europe (e.g., the Low Countries, many Mediterranean islands and parts of Italy) and the New World and that the Austro-Hungarian Empire was a place from which Sephardi Jews in the Levant and the Balkans would trade, settle and consider the essence of western civilization. Things are not as simple as they sometimes appear to be.

[10] By the way, we are reminded, “most Yiddish literature isn’t particularly funny except in a horrible, un-American way: comically-told plots in which people suffer terribly or die horrible deaths” and “This depressing aspect of Yiddish literature has a profound source beyond Jewish historical realities: Jewish tradition is fundamentally sceptical of art…” Dora Horn, “Why Yiddish is Funny” Tablet Magazine (16 October 2017) online at http://www.tabletmagaizne.com/jewish-arts-and-culture/246994/why-yiddishisfunny ?utmsource = tabletmagazinelist&utm_campaign=4f99ed7ee6-E

[11] Norman Simms, “Universal and Intimate: Acquired Languages in Elias Canetti” in New Zealand and the EU: Perspectives on European Literature, ed. Hannah Brodsky, The Europe Institute 3:2 (Auckland, NZ: 2009) pp. 43-70.

[12] See the novels of another Sephardic Nobel Prize-winning Jewish author, Albert Cohen, such as Belle du Seigneur, about his family background on the Greek island of Corfu.

____________________

Born in Brooklyn, NY in 1940, Norman Simms was educated in the United States, before moving to Canada in 1966. In 1970 he moved to New Zealand with his wife and two young children and taught for more than forty years at the University of Waikato (New Zealand), with stints at the Nouvelle Sorbonne in Paris and Ben-Gurion University in Israel. He founded the interdisciplinary journal Mentalities/Mentalités in the early 1970s and saw it through nearly thirty years. In the two decades since retirement, he has published three long books on Alfred and Lucie Dreyfus and a two-volume study of studies of Jewish intellectuals and artists in late nineteenth and early twentieth century Western Europe, Jews in an Illusion of Paradise; Dust and Ashes, Comedians and Catastrophes, Volume I, and his newest book, Jews in an Illusion of Paradise: Dust and Ashes, Falling Out of Place and Into History, Volume II. Several further manuscripts in the same vein are currently being completed. Along with Nancy Hartvelt Kobrin, he is preparing a psychohistorical examination of why children terrorists kill children.

More by Norman Simms here.

Please help support New English Review.