by Peter Hitchens (July 2018)

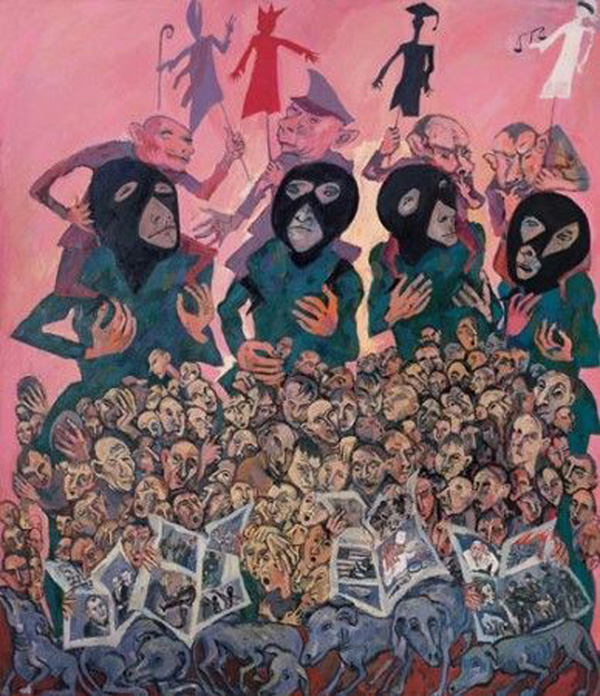

Structure of Democracy, Maxim Kantor

Why do we not like to think about Democracy, even though we know that there is much to be said against it? Probably because we are afraid to do so, scared of being called rude names and accused of wicked sympathies. I have heard dozens of conversations on the subject end so abruptly I would not have been surprised to hear an audible “click” from the heads of those involved, by someone quoting part of Winston Churchill’s November 1947 remark to the House of Commons. I have emphasised the passage most often remembered: “Many forms of government have been tried and will be tried in this world of sin and woe. No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others that have been tried from time to time.“

But is this actually true? Do we use the word “democracy” to describe a system which often but not always coincides with democracy, but is not democracy? Recent events in Turkey, where Recep Tayyip Erdogan has used democracy to wipe out liberty and law in his country, are one example of this problem, from which we turn our pained and puzzled minds. There was already another equally strong example, in Germany in 1933. But it was so powerful and obvious that, by a strange paradox, nobody remembers it and it fails in argument. I suspect this is because we have consigned all the events of the Hitler era to a special shelf in the Cupboard of the Yesterdays, marked “Wholly exceptional. No lessons to be learned here.”

And yet there are lessons. Perhaps we can get them somewhere else. Before visiting China was fashionable and before its big cities became rich, I made one of the most fascinating journeys of my life, flying up from what was then British Hong Kong to Communist Peking. In those days people had not yet started calling the Chinese capital “Beijing,” a wholly illogical and inconsistent cultural cringe which I still refuse to follow. I don’t call Rome “Roma,” Prague “Praha” or Moscow “Moskva,” and I certainly don’t call Dublin “Baile atha Cliath,” so why should I call Peking “Beijing?” Great world cities should be pleased to be so famous that they have acquired foreign names. Am I upset that the French call London “Londres,” or the Poles call it “Londyn?” Not even slightly. But a resurgent and very nationalist China seems furiously keen on enforcing “Beijing.” So I am equally keen on not doing as they wish. This is because I am very fond of freedom, and regard present-day China as the single most menacing threat to that precious possession.

And this brings me back to that journey, right at the end of the old world, which died during the 1990s, and which we did not value enough. In that world, freedom was still synonymous with prosperity and civilisation, and despotism equally synonymous with dusty poverty and squalor. Colonial Hong Kong was one of the best places to examine that division (the others were Korea and Berlin). But (unlike West Berlin and South Korea) Hong Kong was never a democracy, something which embarrassed many at the time, and would be a painful issue when, in 1997, Britain handed its former possession over to the Chinese Communist Party. Peking was easily able to argue, against those who sought a democratic system of government in the new Special Autonomous Region, that Britain had not granted any such thing, so why should they? But I doubt it would have made much difference to what happened afterwards. Peking’s unrelenting attempts to squeeze freedom out of Hong Kong were ultimately unstoppable, even if there has been some very brave resistance to them.

Before the 1997 handover, authority in Hong Kong lay, ultimately, in London, and was exercised through a civil service and a legal system based upon British law and practice. You might say that the British had democracy at home, but you might equally well have said that the American colonists in 1776, or the Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders who came to develop their own representative institutions, also benefited from British democracy at home.

Yet, especially after a visit to Peking, in those days still very much a grey, conformist and startlingly poor Communist city, undemocratic Hong Kong was astonishingly free, clean, prosperous and, well, happy. Its courts were generally fair and its press was vigilant. It suffered comparatively lightly from the corruption which flourishes like a rank fungus in the dank shadow of unaccountable authority. After the grubby secret police state of China, where they think “the rule of law” is a synonym for “police state,” Hong Kong was a joy. Perhaps above all, its free press and the general ability of everyone to say what they thought was a wonderful change after a few days in the dreary brain-dead city to the north. Yet both places were in the same country and both were formed by the same culture and thousands of years of recorded history.

Suddenly, a heretical thought began to form in my mind. Perhaps democracy was not the vital distinction everyone seemed to think it was. Perhaps it was not the same thing as liberty.

Like the mustard seed in the parable, “which indeed is the least of all seeds: but when it is grown, it is the greatest among herbs, and becometh a tree, so that the birds of the air come and lodge in the branches thereof,” this suspicion grew and grew in my mind.

I had noticed that not much good had come from the arrival of universal suffrage democracy in Russia, and the other former Communist countries, after the fall of the Soviet Empire. Our enthusiasm for it was not all that it seemed. When Boris Yeltsin sent tanks to shell his own Parliament, the “free West” looked on, smiling indulgently, and I have to confess I was not especially distressed myself at the time, though I have come to be ashamed of that. This is not because it was a betrayal of “democracy” but because it was just cynical, especially set beside our more recent loftiness about the Putin regime’s crimes. Later we affected not to notice the blatant buying of votes for Yeltsin’s re-election. Who can really blame them? If they had not, then it is quite possible the Communists, of all people, would have won. Imagine the effect of that. I had watched unconvinced the supposed introduction of democracy in post-invasion Iraq, and the nonsense on stilts of the “Arab Spring,” most especially in Egypt, where suffrage empowered the Muslim Brotherhood (just as everyone had said it would) and the pro-democracy West had to remain silent when a military putsch swept the Muslim Brothers away and those who defended the democratic verdict were massacred on the streets of Cairo or crammed into filthy jails after fake trials. If we don’t mean what we say about democracy abroad (and we do not), do we mean what we say about democracy at home?

I do not think so. Otto von Bismarck said that if you liked politics or sausages, you would be wise never to watch either of them actually being made. And this is true. I worked for some years in the bowels of the British Parliament and found not a kingdom of the mind, where wise rulers sought the best, but a squalid place of deals and gossip. Most important, the apparent division between the two tribal parties was an illusion. They had far more in common with each other than they liked to let on. And any thoughtful analysis of the election system revealed two crucial things. First, the candidates were selected in safe districts (where one party was almost bound to win, and the other almost bound to lose) by small, secret party committees. Secondly, there was seldom if ever a genuine ideological or political contest. The committee-approved candidates, already in debt to the party leadership, were approved by an electorate which voted purely on tribal lines. Genuine popular revolts against this system were extremely rare, and usually short-lived.

Everywhere in democratic countries one hears the complaint that “if you put up a chimpanzee/yellow dog up round here under the right party label, he’d win.” And everywhere this is true. So, in what way are the alleged representatives of the people truly chosen by them? On the contrary, they represent the political parties, and in the end the government, to the people—not the other way ’round. There used to be far more independence of mind, and resistance to the executive, in the old hereditary House of Lords, whose members owed their places to an undemocratic King or Queen long dead, than there ever was or now is in the supposedly democratic House of Commons. Its members owe their places and incomes to an undemocratic party machine which is still very much alive.

As for the raising and spending of money by parties, and the dependence of those parties on the endorsement of the major broadcasting organisations (themselves controlled by self-perpetuating elites), it does not bear thinking about. Broadcasters nowadays act much like the mediaeval church, bestowing blessings on the chosen party and excommunicating the unchosen one. This has had a very interesting outcome in Britain where the Labour Party, formerly endorsed by the BBC because of its reliable Gramscian Eurocommunism (the ideology of the British governing classes), adopted a cruder and more blatant form of leftism. As a result, the nominally “Conservative” Party, whose leaders pursue Gramscian Eurocommunism without being able to pronounce it let alone understand it, has the BBC’s support instead. The newspapers play a smaller and diminishing part in this but, in Britain, partisan journalism still polices Parliament very strongly and any MP shown to be out of step with the general politically correct view of almost everything will often be destroyed by it—almost certainly with the covert help of his or her own party machine. Genuinely individual voices are very rare indeed. Elections themselves are often conducted by the use of shameless dishonesty and misrepresentation and, in Britain, political advertising is specifically exempt from rules which stipulate that commercials for soap or automobiles must be “legal, decent, honest and truthful.”

This is why Churchill and Bismarck knew perfectly well that the haloed public image of democracy was and always would be false. So does anyone who comes into much contact with it. But when I have occasionally (and with deliberate mischief) said in public that perhaps democracy is not all that wonderful, I have felt a frisson of irrational rage run through the room. It is the sort of thing which could easily get you howled down, and then perhaps driven out of public life if you persisted in it. I could almost hear the unspoken hiss of “fascist!” from my fellow-speakers on the platform and from the audience. Pointing out that Hitler came to power democratically, though it is a very potent answer to the charge that suspicion of democracy makes me a “fascist,” would not have helped me against this irrational rage. At least, this was so until recently. Yet now, after the victories of Donald Trump in the US presidential election and the defeat of the European Union’s supporters in the British referendum of 2016, I find that the sort of people who would once have called me “a fascist” are developing their own doubts about democracy. Having used it for decades to pursue their own ends, they now find the weapon turned against them and are not so sure about it.

Well, they are opportunists, who have reached the right conclusion out of wounded self-interest rather than honest open-minded thought. Even so, their conversion may make it easier to discuss the matter. Liberty and the rule of law are the great treasures which arose out of England’s unique history and only truly exist in the Anglosphere (and perhaps, in another form, in Switzerland). In general, they are founded on the Magna Carta principle that law must stand above power, in unanimous jury trial and the practical presumption of innocence, in habeas corpus, protection against self-incrimination and double jeopardy, in freedom of speech and assembly and in adversarial parliaments where the opposition always stands ready to replace the government. They came into existence in Britain in 1689, in the USA a century later, where Thomas Jefferson based the Bill of Rights on the earlier English one, including, interestingly, the Right to Bear Arms. This was long before universal suffrage democracy came to either country.

In Britain, full universal suffrage did not arrive until 1948, when the graduates of the great universities of England and Scotland lost their extra votes. Many poorer men (and all women) were denied the vote before 1918. In many parts of the early USA, the principle of “no representation without taxation,” which is after all the corollary of “no taxation without representation,” meant only 70% of adult males at first qualified for the vote. This proportion grew during the mid-19th century, largely because political parties wanted to expand the market for their lies and promises and so diluted the property qualification. Votes, contrary to myth, are much more often given away than fought for. Secret ballots did not come to the USA till the late 19th century. As for the USA’s black-skinned slave and freed slave population, we all know how recently they were allowed the vote in reality.

The US Senate was specifically designed to be protected from what Edmund Randolph, first Attorney General of the United States, called “the fury of democracy,” hence the fact that Senators have much longer terms in office than members of the House of Representatives. Until the passage of the 17th Amendment in 1913, which faced strong and honourable opposition from several leading figures, U.S. Senators were not elected by popular vote, but chosen by their state’s legislatures.

The USA also has a third and wholly unelected chamber of government, the Supreme Court, which is in many ways more powerful than either the House, the Senate or the Presidency. Many of the most radical changes in American life, notably the legalising of abortion, have been brought about by this body. I suspect that social liberals would be alarmed at any suggestion that it should be democratically elected. I too would be alarmed. An elected court would be unlikely to contain another Antonin Scalia. Democracy in Britain has, in recent years, abolished unanimous juries, the rule against double jeopardy and the right to silence. It has whittled away at the presumption of innocence, especially in rape cases. On the pretext of countering terror, it has attacked habeas corpus. The Patriot Act has done similar things in the USA. Social media, surely a form of direct democracy, has become a terrifying engine of intolerance and electronic mob rule.

Was there, is there, an alternative? The only coherent suggestion I have seen for a recapture of the parliamentary system by the educated and informed can be found in a forgotten popular novel by Nevil Shute, an aircraft designer and engineer who flourished in the mid-20th century. In his book In the Wet, Shute outlined an ingenious system of multiple votes, in which all adults started with one vote, and were awarded more (up to a maximum of seven) for various achievements unconnected to inherited wealth, such as successfully raising children, serving in the military, or performing acts of selfless courage. The seventh vote was a rare honour, the personal gift of the monarch. In the book, the main effect of the multiple vote system is that governments stop trying to bribe people with their own money. The idea is so clever that probably only an engineer (described by Shute as “a man who can do for 50 cents what any fool can do for a dollar”) could have thought of it. It will never happen, but is that a good thing? Perhaps there is a better system than democracy, but it is difficult, and so will not be tried.

_______________________

Peter Hitchens is a British journalist who lives in Oxford. He has worked for more than 40 years as a reporter and writer for popular national newspapers covering politics, international affairs, defence and diplomacy and working as a resident correspondent in Moscow in the last days of Soviet power. He is presently a columnist for The Mail on Sunday. He calculates that he has reported from 57 countries, including North Korea, Bhutan, and Venezuela. He is the author of several books, including The Abolition of Britain, a description of the British moral and cultural revolution.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast