Earlier Thoughts

by Theodore Dalrymple (July 2020)

Man Reading in the Studio, Kmetty János, 1930-39

There are few of us, I should imagine, who would care very much to have their thoughts at the age of twenty about life, literature and the world, exposed to public view and widely disseminated. Our thoughts at that age, though no doubt essential to our personal development, were hardly worth having, or at least not worth communicating to others. In short, our thoughts were callow, shallow, hackneyed and unoriginal in the extreme, often uttered with that youthful combination of arrogant certainty and underlying insecurity which manifests itself as a kind of inflamed prickliness whenever challenged.

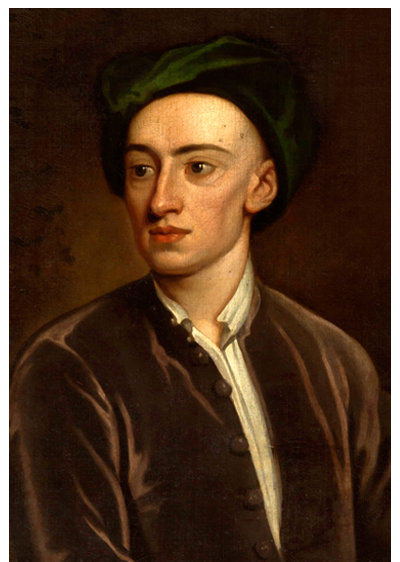

As with most generalisations about humanity, this is not true in every case. When I think of those who do not deserve these strictures, I think first of Alexander Pope. He wrote his great poem, An Essay on Criticism, when he was only twenty years old, when he displayed at that age a maturity of judgment, and a felicity of expression, that most of us cannot remotely aspire to even at the age of seventy.

Many of his lines are worth all my thoughts at the age of twenty combined (and possibly all those ever after), for example:

True Wit is Nature to advantage dress’d,

What oft was thought, but ne’er so well express’d.

Or

True ease in writing comes from art, not chance,

As those move easiest who have learn’d to dance.

He has excellent advice on vocabulary for the aspiring writer. Speaking of the use of words, he says:

Be not the first by whom the new are try’d,

Nor yet the last to lay the old aside.

Nor should we judge of literature by extraneous considerations:

Regard not then if Wit be old or new,

But blame the false, and value still the true.

The young Pope has insight being his years into human types:

Some praise at morning what they blame at night;

But always think the last opinion right.

Then there is:

The bookful blockhead, ignorantly read,

With loads of learned lumber in his head,

With his own tongue still edifies his ears,

And always list’ning to himself appears.

Whenever I read the first and the last two lines of these quotes in particular, I cannot prevent the thought of a certain famous person, a renowned writer, from entering my head. His certainty is like the grin of the Cheshire cat: it is what remains behind when everything else in his opinion changes; and certainly ‘always list’ning to himself appears.’ But I shall not reveal who he is, for it is not my desire to wound.

Whenever I read the first and the last two lines of these quotes in particular, I cannot prevent the thought of a certain famous person, a renowned writer, from entering my head. His certainty is like the grin of the Cheshire cat: it is what remains behind when everything else in his opinion changes; and certainly ‘always list’ning to himself appears.’ But I shall not reveal who he is, for it is not my desire to wound.

It is surely remarkable that a poem by a twenty year old on a subject as abstruse (to the modern reader) as criticism should have given three phrases entered into the English language: a little learning is a dangerous thing; to err is human, to forgive, divine; and Fools rush in where Angels fear to tread.

Few are the Alexander Popes of this world, however, who think anything at the age of twenty that is worth repeating or pondering nearly three hundred years later. I blush to think of the banality of my own opinions at that age; I once threw my diaries into the dustbin in disgust, though I ought really to have burned them to make their destruction absolutely certain (I still suffer from a slight anxiety that someone might have found and preserved them). Therefore, I pity those poor adolescents and young adults, who have been unwise enough to entrust their immature thoughts to a medium from which they cannot be erased. Be sure your opinions (these days) will find you out.

Some juvenilia are interesting, not for their intrinsic worth, but because they are the early emanations of a talent that was to develop later. Rearranging the piles of books in my study, as I do regularly in the hope that I will thereby tidy them or achieve order, I came across a book I bought in 2015 and had always intended to read, a collection of E. M. Cioran’s early journalism.

Cioran, a Romanian born in 1911, left his country definitively in 1941 and lived the rest of his life in France. There he became a celebrated if unsystematic philosopher, his stock-in-trade, as it were, being a kind of disabuse with life and existence, one of his titles being The Inconvenience of Being Born, expressed in lapidary prose which (it is commonly asserted) made him one of the greatest prose stylists in French of the Twentieth Century. He was fond of aphorisms: here are three from his last book, Anathemas and Admirations:

Tyranny destroys or strengthens the individual; freedom enervates him until he becomes no more than a puppet. Man has more chances of saving himself by hell than by paradise.

and:

One work of piety declares that the inability to take sides is a sure sign one is not “enlightened by divine light.” In other words, irresolution, that total objectivity, is the road to perdition.

and:

Vehement by nature, vacillating by choice. Which way to tend?

With whom to side? What self to join?

It is difficult not to see, in these and in many others, a reflection of Cioran’s past, which he partly admitted the better to disguise it. For the fact is that, in his youth (aged 22) to his early maturity (aged 30), having previously been apolitical, became an ardent admirer of Hitler and as late as the age of 29 wrote a fulsome, indeed nauseatingly hagiographic article in praise of Codreanu, the vicious, murderous leader of the Rumanian Iron Guard, a kind of Romanian S.A. and S.S.

It has sometimes been said in his defence that when Cioran (R), as a student of philosophy in Berlin in 1933, first developed his admiration for Hitler, he could not have known where it was all going to end. True enough, though it was hardly possible that the early viciousness of the Nazi movement and regime escaped him. But no one could have been unaware in 1940 of the thuggish brutality that Codreanu (who was killed in 1938 on the King of Romania’s orders) had unleashed. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that Cioran admired—worshipped, actually—Hitler and Codreanu not despite their brutality, but because of it. Of course, in the light of events he had to back-pedal: and in the France of 1945 it would not have done to admit to an enthusiasm for Hitler and his Balkan imitators. On the other hand, to claim to have been a résistant would have been to draw attention to himself and possibly have led to an investigation. It was far, far safer to appear as a world-weary person disengaged entirely from the concerns of most people, having seen through the meaninglessness of existence.

It has sometimes been said in his defence that when Cioran (R), as a student of philosophy in Berlin in 1933, first developed his admiration for Hitler, he could not have known where it was all going to end. True enough, though it was hardly possible that the early viciousness of the Nazi movement and regime escaped him. But no one could have been unaware in 1940 of the thuggish brutality that Codreanu (who was killed in 1938 on the King of Romania’s orders) had unleashed. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that Cioran admired—worshipped, actually—Hitler and Codreanu not despite their brutality, but because of it. Of course, in the light of events he had to back-pedal: and in the France of 1945 it would not have done to admit to an enthusiasm for Hitler and his Balkan imitators. On the other hand, to claim to have been a résistant would have been to draw attention to himself and possibly have led to an investigation. It was far, far safer to appear as a world-weary person disengaged entirely from the concerns of most people, having seen through the meaninglessness of existence.

Fortunately for him, he had written his pro-Nazi and pro-Iron-Guard articles in Romanian, a language with which few people were familiar. Moreover, his writings would not be easy to access after the war. His tactic of both covering and uncovering his traces was a very shrewd one, but his past clearly worried him to the end of his life (he died in 1995, aged 84), because his one commitment in life, to Nazism both German and Rumanian, responsible for some of the worst atrocities in human history) was so unavowable. He never committed to anything again, keeping his head below the parapet so to speak, for in commitment lay danger. No wonder he was ‘vehement by nature, vacillating by choice.’ At the same time, pride could not allow him merely to admit (to himself and no doubt to others) that he had sided with evil purely out of stupidity. Hence, to repeat:

Tyranny destroys or strengthens the individual; freedom enervates him until he becomes no more than a puppet. Man has more chances of saving himself by hell than by paradise.

In other words, by siding with tyranny, he had really made almost a wise choice, giving Man more of a chance to save himself than if he had made any other choice.

There are some very startling passages in Cioran’s juvenilia, which perhaps should serve as a warning to any young person tempted to post his opinions on Facebook or Twitter. Thus, in November, 1933, he wrote:

If Germany of today has achieved something, if the Germans live in a mad enthusiasm and in an admirable effervescence, it is because at a given moment they have had the courage to liquidate, a fecund and creative passion, the ability to take infinite risk, and above all a messianism that foreigners find difficult to understand.

This was no passing infatuation. Seven months later, he wrote:

No politician in the contemporary world inspires as much of sympathy as Adolf Hitler. There is something irresistible in the destiny of this man, for whom every act in life has significance only by symbolically partaking of the historical destiny of a nation.

And after the Night of the Long Knives, he protested at those who saw it as murderous thuggery (both victims and perpetrators were thugs, of course):

They say: no one has the right to take the life of another, no one has the right to spill blood, no one can dispose of the life of another. Man has a value in himself, etc. But I ask you all: what has humanity lost if the lives of some imbeciles have been taken? (…) Our disgust towards Man is so terribly legitimate that the death of a few nullities cannot impress us . . . Ah! This prejudice that Man is a value in itself! Why a value in itself? By what right? When one sees that the majority of humanity is so little bothered by, does not care about, the meaning of the world or lack of it, to mutter a few abstract formulae foes not authorise us to make absolute demands.

You don’t have to be a fully paid-up believe in a plethora of rights to find this authentically disturbing and indeed horrible. Cioran believed that killing nonentities (such as he was not) was hardly a crime, and certainly nothing to lose sleep over.

And yet he was a man—albeit still young—steeped in philosophy and literature, and very far from stupid. Perhaps what is most alarming about his early writing, apart from the kind of sentiments I have quoted (and there are many more where they came from) is that his diagnosis of what is wrong with our civilization is sometimes not dissimilar from our own.

Cioran was acutely aware of and humiliated by, the fact that Romania had had an inglorious history and was what he called a minor or small culture, from which derived the Romanians tendency to imitate. That Bucharest was known as ‘the Paris of the Balkans’ sums up what for him was all that was bad about Romania.

But he also looks with a distinctly jaundiced eye on contemporary western civilization as a whole. (All seems infected that the infected spy—Pope says—As all looks yellow to the jaundiced eye.) He says, for example, that what he calls ideocracy, the overvaluation of ideas:

. . . has led to an excessive domination by formulae. What is worst about this phenomenon is that it suffices to adhere to a doctrine or certain of its aspects to be assimilated to its whole. The tendency to the doctrinaire is the worst calamity of the age because it necessarily involves a conscious, rational search for formula . . . that excludes all spontaneity.

The formulae are then imposed, says Cioran: one has to take them seriously and submit to them. He continues:

The ideocratic esprit has never been more intolerant, sterile and implacable with the individual than it is now: it continuously opposes the tyranny of formulae to the spontaneous productivity of the individual.

Surely he is speaking of 2020 rather than of 1932? Certainly I do not recall in my lifetime any time when the ideocrats were so powerful, determined and nasty.

We must be careful never to have the same reaction as Cioran: never to opt for the barbarism he extolled, whatever the problems we face.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Kenneth Francis) and Grief and Other Stories from New English Review Press.