Emergency Underpants

Always be sure to have clean underpants. You never know when there might be an emergency.

by Steve Jamnik (February 2022)

My Auntie Iris had an ineluctable sense of humour. She would rib me every time we visited her. She would say: “Have you started courting yet?” (I was seven years old.) Or: “Have you passed your driving test?” Then there was: “I hope you’re wearing clean underpants in case there’s an emergency.” And I would have to say on cue: “What emergency?” And Auntie Iris would reply with something shocking and over-dramatic: “You could get run over by a bus!”

Since we lived on a farm and the nearest bus stop was two miles away, I always felt that the underpants scenario was a low probability risk. But one night, one dark evening in the sixties when I was only fourteen years old, I came face to face with the terrible wisdom of that particular piece of advice.

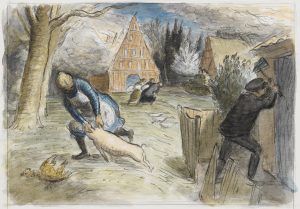

The farm we lived on at the time was part arable, part pig farm. My father handled the arable side, growing barley and wheat. The wheat was sold to the local grain merchant. The barley was stored in the farm’s granary, and was milled to provide meal for the pigs throughout the year.

Pigs are a demanding stock to rear. They are unbelievably noisy at feeding times. They squeal and fight in the troughs, sounding as if they are being slaughtered rather than fed. They need feeding twice a day, three hundred and sixty five days a year. Pigs don’t do Christmas. They also need frequent mucking out. Although we had one small pig field on the farm, all the other fields were cultivated, and the pigs lived either in sheds, or circular, portable, galvanised steel Pigloos positioned in concrete yards. Everywhere had to be hosed down regularly.

For those of you not familiar with the subject, I can tell you now that pig faeces is one of the most remarkable products in nature. It adheres to any surface at any angle and at any temperature. It persists throughout all weather conditions. It is insoluble in water, no matter the pressure of the jet from the power hose. It has a sweet, sickly smell that clings to clothes and skin for days on end, and lurks at the back of the nostrils like a bad cold. Once smelled, never forgotten.

The crowding, effluvium, flies and moisture made the pigsties a haven for disease. The pigs were forever getting ill. Piglets died regularly, either through scours, infections, or the clumsy fat sows treading or lying on them. Then there were the bacterial infections like E-coli. There also seemed to be a fundamental problem with the drainage. Even the house in which we lived wasn’t on the main drains. Our sewage simply flowed into a nearby pond, where the bullrushes grew as tall as poplars. And for a garnish, the farm had a thriving population of long-tailed rodents, in various shades and sizes.

Owing to these tenacious problems, it was impossible to maintain a robust pig herd and very difficult to retain robust pig men. They would arrive, wrestle with the pig problems for a year or so, concede defeat, move on; and a new pig man would arrive and the process would begin all over again.

One chilly night, my father went into the porker house and found John – our latest pig man – on his knees on the cold concrete floor, head bowed, hands clasped in prayer.

“What are you doing John?”

“Well I’ve tried everything else, George.”

Word began to get around that our farm was a sticky wicket, which is why I suppose we ended up with Billy Smith as the very last ever pig man on our farm.

Billy Smith would today probably be diagnosed with obsessive-compulsive-narcissistic disorder, with a touch of delusions of grandeur and autism thrown in. Of course this was the sixties. Pig men didn’t have psychological disorders in those days. Everyone knew that the pigs were an intractable nightmare. It was no surprise if they drove a sane man round the bend. But sane men cope with insanity. They don’t go completely insane. They shout and swear and stomp around and then hand in their notice. But this is not what Billy did.

For a pig man, Billy had the most beautiful handwriting I had ever seen. It was Copperplate. All the pigs’ vaccination records were filled in in the most elegant hand written script. The medical charts hanging in the pig sheds looked like medieval religious manuscripts. Then there was Billy’s tireless attention to detail. All doors to be locked shut when not open. All passageways washed and spread with clean straw. Rubber gloves to be worn at all times. Special gumboots to be worn in the sheds, and dipped in buckets of white disinfectant on entry and exit. No playing in the pigsties. On and on the regulations went. Everything had to be controlled, charted, logged, assessed, checked, patrolled, reviewed and finally written down and locked up. It became difficult to do anything on the farm without Billy’s permission, and certainly without him knowing about it; and soon Billy was attempting to control every aspect of running the farm.

This began to put my father’s back up, but when you’re fourteen years old you don’t pay any attention to what the adults around you are getting up to. I was supremely oblivious to everything, and quite unaware of the ugly mood of stress, resentment and anger building up on the farm.

And that’s without even considering Lydia, Billy’s wife. Yes, Billy had a wife. One wonders what life must have been like in the Smith household. I had no idea at the time, and not the slightest interest, but in retrospect, what happened on the farm a few months after the Smith’s arrival doesn’t surprise me at all.

It was a Saturday afternoon when things kicked off. My father, mother and I were in our kitchen, the warmest room in the house because the stove was always kept alight. Lydia knocked on the door. Could she store some things in our outside shed? Yes all right. What sort of things? Well, ‘domestic things’ like blankets and shoes and a kettle and a latch hook rug kit. A most peculiar assortment of items. Why did she want us to store them?

We learned that Lydia was in the process of leaving Billy. Life with him had become so intolerable with his rules and obsessions and his frantic and increasingly desperate attempts to get on top of the problems with the pigs, that Lydia’s life was misery from morn until midnight.

Earlier that afternoon, unbeknown to us, she had lured Billy out of the house with a decoy telephone call from a confederate. While Billy was out on his wild goose chase, Lydia had gathered together a few desultory possessions, dumped them in our shed and was waiting patiently in our kitchen for her confederate to turn up with his car and whisk her, together with her latch hook rug kit, away from the hell and the smell of life with Billy, to a new life free from farming, flies and farrowing houses.

It was about six o’clock in the evening and already dark. We all sat in the kitchen talking quietly. Slightly embarrassed, because we realised we were conniving at a deception. Not at all the sort of thing my father was inclined to get involved with. Nor my mother, although she sympathised with Lydia’s plight. We lived with the same fumes and flies, if not the full complement of obsessive compulsions.

Suddenly I noticed our dog’s ears prick and his neck go stiff. He went rigid. Everyone in the kitchen stopped talking. Everyone stopped breathing. There was a three and seven-eighths of a second moment of complete silence. Even the clock on the mantlepiece stopped ticking. Then there was an ear-splitting crash as the kitchen door exploded open. Roaring like a tornado, Billy came screaming and raging into the kitchen, lashing out with an enormous ball peen hammer clenched in his right hand.

“I’ll murder her! I’ll murder her!” he screamed like a demented maniac.

Dad leapt instantly from his chair and made a grab for the hammer, trying to wrest it from Billy’s fist, yelling urgently at mum:

“Get his legs, get his legs!”

Mum dropped down onto the kitchen rug on which Billy and my father were struggling, seized Billy’s ankles, and gave them an enormous tug, whisking Billy’s feet from beneath him. Down went Billy with my father on top, fighting to restrain him. Lydia fled shrieking and screaming out of the kitchen, along the hall and into our downstairs toilet. She locked herself in, whereupon she proceeded to barricade the door with toilet rolls, the S-Bend brush, the toilet plunger and our big mop with the red handle.

Rolling on the kitchen rug, my father clung to Billy in a bear hug, but Billy was thin and wiry, and as much as my father tried to grip and subdue him, Billy simply wriggled and squirmed, first escaping from his coat, and then his cardigan, succeeding in getting himself free.

“Get the hammer. Get the bloody hammer!” bawled my father. I obediently reached in among the flailing arms and legs, and grabbed the hammer lying on the floor. I ran out of the kitchen and upstairs to my bedroom.

I had no idea exactly how dangerous the situation was, or whether my father would be able to overpower the raging lunatic who was thrashing and fighting on our kitchen floor. What if he did break free, gave everyone the slip, and came up the stairs after me?

I looked desperately around my bedroom for a safe place to stow the hammer. The only place I could think of was my chest of drawers, which had two shallow drawers: the top one for my socks and the bottom one for my underpants. Since underpants took up more surface area than socks, I decided that the hammer would best be hidden tucked beneath the underpants in the bottom drawer, which I gingerly did, being careful not to make any sound that the murderer might hear.

Then I realised that my bedroom door didn’t have a lock on it, so I was completely at the murderer’s mercy anyway. Totally trapped. There was no other way out. So I opened the door to the built in wardrobe, climbed inside and closed the door behind me. Everything in the wardrobe was on the floor rather than on the wire hangers and everything seemed to be stuffed into plastic bags, cardboard boxes or wrapped in brown paper. The crunching sounds made an inordinate amount of noise. And the clinking and jingling of the wire hangers swinging back and forth must have been heard the length of the house.

I stood as still and as silently as I possibly could. My pulse throbbed loudly and heavily in my ears. I heard muffled yells and shrieks from downstairs and then suddenly the noise died down, except for the sound of my mother sobbing.

After what seemed like hours, but which was probably no more than twenty minutes, I realised that deeper, unknown voices were talking in the kitchen. A neighbour had heard the shouting and screaming and had called the police.

I crept out of the wardrobe and tip-toed to the top of the stairs. There was murmuring and movement. I heard my mum bawling her eyes out; and Lydia was still in hysterics and still in the toilet.

Then a tall shadowy shape appeared at the foot of the stairs. I was relieved to see it wasn’t the murderer, who must have been apprehended and carried away by then. It was a policeman, but not wearing his helmet, which disappointed me for some reason.

“Do you know where the hammer is?” the policeman asked me.

“Yes. It’s in the drawer with my underpants.”

“Where is that?”

“In my bedroom.”

“Can you fetch it for me?”

The kind policeman came up the stairs and followed me into my bedroom. I went over to the chest of drawers. I hesitated. I had carefully hidden the hammer at the very bottom of the pile of underpants in the drawer, and I knew that the pair on the top were my favourite, best, brightly coloured, mercerised cotton ones, with a design of spacemen on them. I was terribly worried. I wanted to be helpful and cooperative, but when you’ve got a policeman standing behind you asking for a murder weapon, you don’t want him to know that you’re the sort of person who walks around with spacemen on his underpants.

I opened the drawer discreetly and folded the layers of pants over, so that the policeman wouldn’t see the spacemen. I must have done it quite expertly, because he never mentioned them. He seemed more interested in the ball peen hammer: big, old, thick, primitive, heavy, nasty. I handed it over to him and he thanked me and he went back downstairs.

The farm never recovered from the trauma of that night. Billy was tried for attempted murder and received a custodial sentence, mitigated owing to the provocation of his wife’s stupid ploy. The Smith’s house stood empty for many months. Mum’s nerves were shot to pieces and were never the same again. Dad lost confidence in the farmer and his insistence on raising pigs in such unsuitable conditions and with such unprofitable results. It had been a bad year all round. Within two years the entire pig herd had been disposed of, and the pig sheds either demolished or let out for storage, or as small industrial units.

And of course more than anything, the events of that night demonstrated how wise and useful my Auntie Iris’s advice had been all this time. Always make sure you’ve got clean underpants. You never know when you might need to hide a murder weapon.

__________________________________

Steve Jamnik grew up on farms in South East England, studied psychology at University in the early seventies, worked as a Behavioural Psychologist for two years, then moved into television post-production. He is now retired.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast