by James Como (May 2019)

Concert in the Opera House, Max Liebermann, 1921

I recently wrote that Wuthering Heights is in the “key of revenge.” When I sent that piece to my friend Emily she was struck by the idea that fictions can be in a key: she must re-visit some favorites. Then we would talk it over. As for me, an old accordion player: I know what a musical key is but have no idea what difference a key makes to a piece of music, especially since one key can be transposed into another, retaining exactly the same melodic line, unlike, say, transposing revenge to love (as some have tried to do with the other Emily’s masterpiece). Or do different keys resonate differently with and within our souls? “Auntie Em” (as I call her) would have an answer.

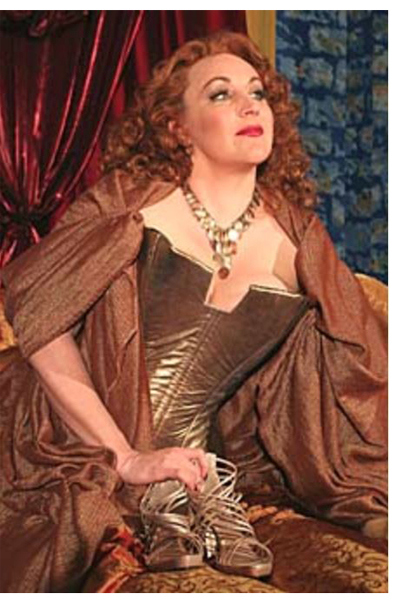

You would believe me if you had ever heard Emily sing—and there is some chance you have, for she is Emily Pulley, the acclaimed operatic soprano. (Whether you’ve had that great pleasure or not, you may hear her in the New York debut of Benjamin Britten’s Owen Wingrave—from the Henry James ghost story—running from May 9th to May 12th, presented by The Little Opera Theatre of New York at the GK Arts Center, 29 Jay Street, Brooklyn.)

Read more in New English Review:

• Light Thoughts on Kingsley Amis

• Children and the Great Blur

• Dysfunction Junction

As it happens, Emily is a woman of many parts: well-read and -traveled, richly cultivated, adventurous, intelligence as commanding as her curiosity, which ranges wide and which she works to satisfy (for example, reading much science as well as hiking mountain trails). She sees connections many of us do not, such as those between colors and music; takes apart concepts and applies conceptual tools (like the three types of rhetorical proof) to her professional life; retains an enormous amount of information—names, bits of conversation from days long-gone, books read and movies seen—all readily retrievable by her.

She is congenial, her vitality overflowing but never tiresome, is not falsely modest, and is utterly unself-promoting. She listens, laughs, conciliates (when necessary), and is no pushover in an argument (despising hidden agenda, as in many novels). She values, and is a most capable practitioner of, the invaluable art of conversation, during which she can be inventive. (“Often we have to build up a passion from the bottom with a scaffold of understanding before we can dive into it from above” —accompanied by unmistakably interpretive gestures.) She is kind. Too kind? She finds something positive to say, always, about any writing I might send along.

Her religious faith, loyalty, and love for her family all run deep; they are touchstones frequently visited, though never intrusively or gratuitously. She lives in Manhattan but is a Texan by both nature and nurture, which makes her, necessarily, both a global city-slicker and a better-than-average horsewoman. She has owned a rifle but doesn’t shoot, plays the bass and the guitar and, on special occasions (as for her niece’s wedding), will compose a song and perform it to her own accompaniment. She works at languages and can (with much hard work) pick up, say, flamenco dancing as necessary.

Her religious faith, loyalty, and love for her family all run deep; they are touchstones frequently visited, though never intrusively or gratuitously. She lives in Manhattan but is a Texan by both nature and nurture, which makes her, necessarily, both a global city-slicker and a better-than-average horsewoman. She has owned a rifle but doesn’t shoot, plays the bass and the guitar and, on special occasions (as for her niece’s wedding), will compose a song and perform it to her own accompaniment. She works at languages and can (with much hard work) pick up, say, flamenco dancing as necessary.

Alexandra and I first met Emily some twenty years ago when I was lecturing at the Center for Christian Studies at the Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church in Manhattan. Each series of lectures ran five weeks, with five series per academic year. (Over seven years I averaged three series per year.) Half of those were on aspects of C. S. Lewis and work related to, or ramifying from, his. Emily attended almost all of them.

She would drop by my college one evening to visit her friend, an old college chum who had also attended the lectures and whom I had hired to teach (possibly the best decision this chairman ever made). It happened to be my birthday. At dinner, a small group of buddies had a cake for me. James (Em’s chum) showed up, as did Emily a bit later. They all sang Happy Birthday; then she sang Happy Birthday. The room was dumb-struck. “Oh,” I said, with as much insouciance as is in me, “this is my friend Emily Pulley, from the Met.” It doesn’t get better than that.

Except it had, and when it did I was afforded the highest peak of Maslow’s Peak Experiences, a hallowed spiritual immersion that very nearly re-baptized me. Some ten years ago, to thank me for the “great good” my lectures had done her, Emily invited my wife and me to see her sing the lead in Dialogues des Carmelites for the New York Metropolitan Opera Company. But there was more. She arranged to have us seated in a private box, mid-mezzanine: the very best seats in the house.

As each nun is beckoned to her death, the crash of the guillotine is heard, and a voice disappears. One by one the frightened, brave women go forth, until one voice remains. Emily Pulley breaks our hearts, and I am soaked in tears, and in gratitude, first to a Providential God who died and is risen for me, second for the gift of friendship that Emily has afforded us, and finally for the gift that God has given this friend. As C. S. Lewis has said, when it comes to friendship, an invisible Master of the Ceremonies has been at work all along. (There cannot be many artists, especially of Emily’s stature, who are more generous than she with her prodigious gift. As a favor, and providing her own accompanist, she sang “Ode to Joy” at the commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of C. S. Lewis’s death.)

We’ve seen Emily perform a handful of times (though not as a flamenco-dancing Carmen). As I listen to her, it strikes me that her voice has a singular quality: dimension. Not just up the scale and down, of course, but depth, as though there were a backup chorus behind the lead timbre. Now Emily sings around the country, often in new works; sometimes, here and abroad (e.g. recently in Toulouse), she teaches master classes. She is away a lot, and that gives rise to a strange feature of our friendship: we do not see much of each other, largely because meeting requires more coordination than is usually the case among friends. But when we do meet we make up for lost time, lunching out ad seriatim and talking, of course: books, movies (lots of movies), sometimes religion, travel, very occasionally politics, professional life, family—quick, lively, thoughtful.

Read more in New English Review:

• Codicils for Coffins: Trump vs. McCain

• Jewtown: Poems of the Rise and Decline of Cork’s Jewish Community

• Plumbing the Depths

When we do meet this month, we will get down to the question of ‘key’. Emily has written, “Britten was less concerned with the traditional use of keys in this piece and was experimenting with tone rows (repeated sequences of notes) and motives (Paramore and its portraits, certain individuals, and various concepts all have musical phrases connected with them). It’s one of the things that adds depth to Britten’s music. Whether perceived or not, the complexity is thoroughly thought out, and as challenging as the score may be, the difficulty isn’t arbitrary, as might seem the case with modern composers.”

Okay then. My plan is to sing a few bars of “Row Your Boat” twice, in different keys (I will have no idea which keys, but I do have a strong range of three, even three-and-a-half, notes), and ask, “what’s the difference? Why can’t all music be written in the key of C?” (No sharps or flats!) Well, that’s half the plan. The other half is for Emily to demonstrate why I’m wrong. Now, I recall that Emily sees much music as color, so she’ll probably say something like, “well, the first, you see, is gamboge, the second fuchsia” —knowing full well that I’m color blind. At which point, alas, I’m left with only one play: “perhaps you can sing the difference?

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

James Como is the author, most recently, of The Tongue is Also a Fire: Essays on Conversation, Rhetoric and the Transmission of Culture . . . and on C. S. Lewis (New English Review Press, 2015). His newest book, from the Oxford University Press, is C.S. Lewis: A Very Short Introduction.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast