by Lorenzo Buj (December 2021)

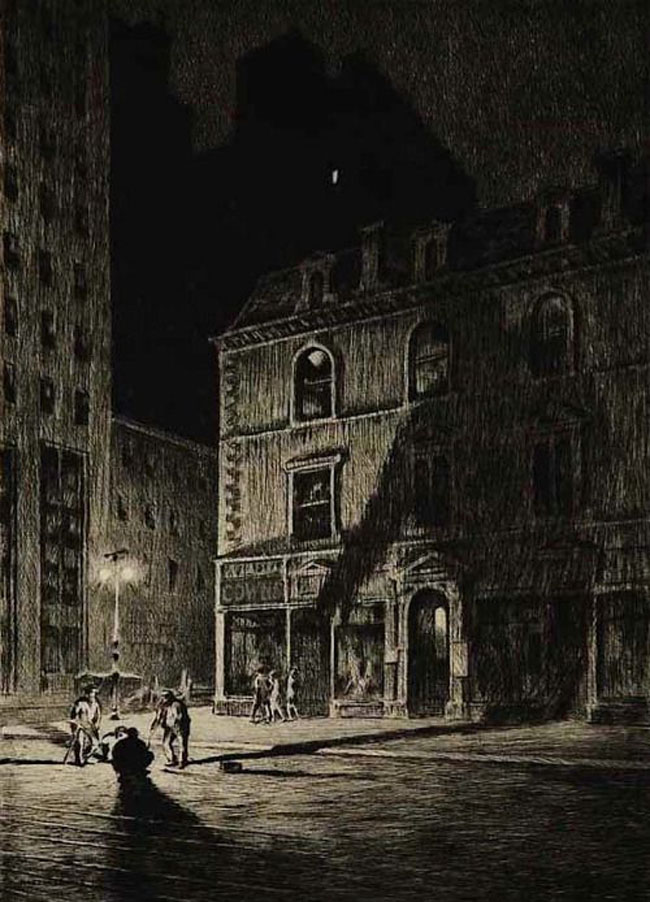

Great Shadow, Martin Lewis, 1925

Arcana Imperii

Eric Ambler’s work belongs to the subgenre of the suspense thriller. More narrowly, the novels focus on espionage and detection within transnational political contexts relative to the real history of the twentieth century: clandestine arms or drug trafficking in the interwar period (between World Wars One and Two); the Nazi and fascist age of the Thirties and Forties; the Cold War as played out in the Balkans and the eastern Mediterranean during the late Stalin era; guerrilla cells and mercenary actions in the Levant and the Far East during the post-colonial epoch. The novels follow a male protagonist who becomes immersed in probing assassinations, conspiracies, or other forms of sub-state or state terrorism. In most cases he is neither a professional spy nor a police detective, but a middle class civilian—a journalist, a language teacher, a ballistics engineer, a playwright, a corporate lawyer, etc.—involved in a race against time. As befits the thriller, whose generic contours Ambler’s fiction helped formulate, the action moves forward with a mounting sense of tension and uncertainty: the protagonist (usually British or American) and his associates (of diverse international backgrounds) must avert or uncover the assassins, the smugglers of forbidden secrets, the ticking time bomb, etc. In the course of doing this, Ambler often employs elements of another subgenre—the crime story. Fictions of this type are often built around a detective who resolves the mysteries of a bygone deed (usually a murder) by discovering the chain of causations behind the act.

At the heart of the political universe that Ambler explores is the fact that power rests on the protection, implementation, or theft of state secrets—what the Roman historian Tacitus named the “arcana imperii.” These secrets can be anything from military plans to sensitive economic policies, formulas for secret weapons, covert operations, disinformation campaigns, shady foreign dealings, etc. In terms of the modern democratic West, which is the perspective from which Ambler’s protagonists encounter the world, this age-old axiom of state secrecy creates ideological contradictions. More profoundly, it points to the corruptible moral substance underlying the business of civilization, Western or Eastern. For if effective governance involves secrecy, leaders are bound to make cold, amoral calculations in the name of sovereignty and national security. But the likelihood of abusing such political prerogatives is well-known. Unscrupulous ministers or heads of state could use national security to evade accountability or, if expedient, to validate the suppression of domestic political opponents. “McCarthyism” in 1950s America was an infamous example of such abuses, but another—and far, far worse—example was the series of purges and show trials that Joseph Stalin orchestrated in the Soviet Union between the 1930s and his death in 1953. Similar policies were enacted in Stalin’s ring of east European satellite states in the decade following the end of the Second World War.

The worldview that emerges from the narrative folds of Ambler’s fictions is both modern and age-old. It is modern in the sense that it silently adopts the thesis of Machiavelli’s The Prince (1513), a short, pungent text rightly renowned as the founding document of modern political science. It is age-old in the sense that Ambler, in a work such as Judgment on Deltchev (1951), tries to make sense of the intrigues of an east European police state by reaching back to the trial of Socrates. We are not to forget that Machiavelli’s modernity was rooted in humanist learning and that the author of The Prince was conversant not only with the story of Socrates but with Aristotle and other classical figures form the western canon, including Cicero, Livy, and Tacitus. Ambler writes spy stories, not political science treatises, but the two are not dissociated, particularly since his novels explore the shadowy forces shaping twentieth century history. The worldview proposed in Ambler’s novels is this: at its political core, civilization is contaminated by the subordination of morality to power; whether modern or pre-modern, states have always availed themselves of secrecy and intelligence; and as statesmen pursue but one goal—self-perpetuation and the national interest—secret information, secret agents, and secret weapons haunt the modern political landscape.

Fiction, as Aristotle said in his Poetics, is a more philosophical thing than history. While hewing close to historical fact, it can avoid some of the liabilities of naming names and exposing actual deeds. According to Eva Horn’s study, The Secret War: Treason, Espionage, and Modern Fiction (originally published as Der geheime Krieg, 2007), the “bad reputation” of the arcana imperii in our current age is a late development in the history of statecraft:

[F]or centuries, the clandestine arts practiced by far-sighted rulers and skilled generals belonged to an arsenal of techniques designed to support the execution and maintenance of power. Since the arrival of the modern world of political transparency, however, any state secret removed from public scrutiny has aroused suspicion . . . In modern democracies, state secrets are suspected to be state crimes. (p. 24)

[U]nlike premodern regimes that regarded secrecy as a legitimate and necessary instrument of power, modern governments tend to make a secret of their dependence on political secrets . . . As a result of modern democracy’s ideal of transparency and the moralization of politics, secrecy has become precarious and problematic, something seen as both necessary and noxious, constantly in need of legitimization yet never really legitimate . . . Secret operations are not only an integral part of democratic policy, domestic or foreign; political secrets are also an obsession of the public sphere, and object of permanent suspicion and speculation as well as a source of frequent outrage and scandal. (p. 82-3)

The modern espionage story, Horn demonstrates, “tend[s] to merge” with “nonfictional forms of writing” (such as the non-fiction novel, the ex-spy memoir) as it explores the nature of power:

Exempt from secrecy clauses or libel suits, fictions are able to shed light on the basic paradox of the political secret in the modern age: the conflict between the political idea of transparency and democratic control on the one hand and the necessary, or at least inevitable, use of covert actions and secret intelligence on the other. It is in modern democracies more than in any other political system, that the arcana imperii come to embody the inherent self-contradiction of politics by opening up a shadowy, uncontrollable domain of illegality marked by lies, deceptions, cover-ups, theft, disinformation, blackmail, and, in the worst case, murder. It is a gray zone of secret plans and hidden operations that . . . blurs the boundaries between state apparatus and war machine. Only democracies manifest this paradox in all its fearful clarity . . . (354)

Ambler’s heroes are what we might term democratic personae. They are Westerners, at home in civil societies defined by a more or less liberal political culture (free press, free markets, government by consent of the governed, etc.). Their political morality is tacitly committed to the values of the Enlightenment. Initially, this leaves them ideologically unprepared to assess the ingenuity or the capacity for evil among the non-democratic “others” that they deal with. These others can include Nazi agents or unscrupulous Westerners, but more often than not they are men and women of the Balkans or the Levant (the latter term indicating those lands adjoining the eastern Mediterranean, where the sun rises). Ambler’s heroes exit their British or American worlds and are pulled down into a vortex of espionage, criminal subversion, and foreign intrigue. Their journey through these worlds manifests the romantic trajectory of the quest, except that their quests—seemingly practical in the aims to uncover and prevent political crimes or dark dealings—shed a gloomy light on the collective psyche of civilization and bring the hero to philosophical epiphanies that are decidedly absurdist and existentialist in tenor (e.g., the forlornness and contingency of the human condition).

Suspense

The interrelationship of secrecy and plotting is what drives Ambler’s narratives. Conspiracy and deception are his subjects, but plotting also happens to be the structural backbone of fiction and the principle upon which Ambler’s plots are constructed is a kind of slow-boiling escalation of suspense. Suspense is, of course, the device that defines the thriller, and Ambler is a master of its techniques. As a spy/detective writer, the suspense element is his central plot device and must be understood in both its narratological and thematic functions. Narratively, the manipulation of suspense confirms the pre-eminence of Aristotelian categories such as plot and catharsis. It activates expectation and apprehension on the part of the reader while foregrounding the mechanics of plot design. In this sense suspense is not merely an inferior artistic trick common in popular fiction, but a narratological element that combines and condenses the intellectual and psychological dimensions of the thriller or crime genres. The gap between Ambler’s complex narratives and the dark plots laid by his villains collapses in the linear thrill of reading. But Ambler’s craft is subtle and his commitment to suspense does not vitiate his realism nor his hermeneutic of the secret wars shaping modern history.

Suspense heightens narrative drama and creates emotional build-up. It satisfies the needs of ‘naïve’ reading and drowns out, as it were, the deterministic aspect of suspense as a mechanism or device. But since this device is embedded within the investigative flow of the thriller or detective story, in which the protagonist is hard at work side-stepping perils while pursuing rational explanations, suspense can also draw attention to the constructed nature of the fictional world. It allows a critical reader to assess the plausibility of thriller plots and evaluate their degree of realism. I think of this question of the plausibility of ‘realism’ or the engineered nature of ‘mimesis’ as a philosophical matter, regardless what genre or subgenre we are dealing with, for it conjoins the literary design of a given novel or story with the historical setting being depicted.

A novel like Judgment on Deltchev falls within the framework of the Cold War thriller. Allowing for some minor liberties (and deliberate ambiguities) of place and time, it recounts a particular historical situation and its philosophical dilemmas. That is, it translates recent events into fiction and offers an examination of human nature, as well as concrete historical agency, under the pressures of totalitarianism. The characters and their milieu are subject to a suspense plot, but they exemplify Ambler’s analytic of his times. Foster, the chief protagonist, is a London U.K. playwright and the exponent of Ambler’s post-War disillusionment with the Stalinist corruption of the left. Hired by an American newspaper, Foster’s job is to report on the east European show trial of Yordan Deltchev, accused of undermining the state in which he previously played an influential political role. But Foster’s assignment turns into double quest—to determine the nature of Deltchev’s guilt and to uncover an assassination plan that is already well advanced as the novel opens. As the action progresses, the plot grows ever more intricate but remains believable; the atmosphere and the lifeworld of the unnamed east European country (probably Bulgaria) are realistically portrayed; Foster’s search for truth takes on air of suspenseful urgency, and in combination with the novel’s foreboding, mimetic texture, underscores moral and metaphysical issues that hover across the text in the form of citations from Friedrich Nietzsche and Plato. These intersections of Cold War contemporaneity, popular writing conventions, and philosophical topoi call attention to the literary values embedded in Ambler’s thrillers.

Realism and Romance

Ambler is celebrated for his realism, his evocation of menace and mystery through succinct descriptions of setting, atmosphere, and incident. This closeness to gritty facts and plain detailing is unsentimental, as befits the rules and expectations of realism, but behind it hovers the penumbra of the romance, or what might justly be termed the romantic pattern in its abortive, modernist mode. If realism names the category under which the modern novel came into its own in the nineteenth century, with fiction taking on sociological colouring in the shadow of industrial capitalism and the positivistic philosophies of Auguste Comte and Karl Marx, ‘romance’ speaks to the very origins of the novel as a quest narrative.

The origins of the novel date back to Greco-Roman antiquity as well as medieval accounts of knightly deeds and the first picaresque stories that came out of Spain in the sixteenth century. Generally speaking, the romance brings its hero or heroine through a plot that features daunting obstacles, narrow escapes, exotic settings, and magical coincidence; at the end there is the promise of redemption and plenitude; there is felicity as the goal is won; the beloved is attained, the hero comes home to a harmonious social or natural environment (no more deserts, droughts, floods, or plagues)

In his magisterial analysis of literary genres, Northrop Frye contrasted realism and romance, observing that the former is intellectual in orientation and the latter emotional. Realism, along with naturalism—its more scientific variant—is an art of mimesis and plausibility, addressed to the actualities and empirical facts of the ordinary world. Romance, on the other hand, pulls in the direction of myth and make-believe. Realism is answerable to the world that surrounds and stands against the psyche and the exertions of the questing self. Romance speaks to the psyche’s search for idealized fulfillment as it battles against the slings and arrows of fortune and life’s contingencies.

***

What I call “abortive romance” is that modern mode of narrative in which protagonists are trapped in a quest pattern that can reach no transcendental conclusion. Stories lead to bleak, ironic epiphanies concerning the human condition in the face of urban anonymity, labyrinthine bureaucracies, or oppressive regimes. Example of such fictions include The Trial (Franz Kafka) and Nineteen Eight-Four (George Orwell). As romance is snuffed out by the realism of the low mimetic phase of literary history, the great moral and metaphysical codes suffer a lasting eclipse. They are still residually present in the institutions or customs of modern life, but their providential myths are extinguished.

Modes and Genres

Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism (1957), published in the decade that Ambler was attaining maturity as a suspense writer, divided literature into four major categories: tragedy, romance, satire, and comedy; over and above these stood the domain of ‘myth’, that is, stories and symbols that deal with humanity’s ultimate concerns in the realms of value and truth. Frye aligned literary modes and genres with seasonal motifs and a theory of archetypes that, in parts, recalls the ideas of James Frazer and Carl Jung. Frazer studied world religions and concluded that the fundamental symbolic paradigm common to all of them was the story of a god or a divine avatar who dies in Winter (nature as desert or in a state of drought) and rises in Spring (nature reborn and fertile).

Though Ambler may have never read Frye, or read him closely, his cleverly titled autobiography Here Lies Eric Ambler (1985) reveals that he was a reader of such figures as Jung, Winwood Reade (a Victorian-era student of Druidic mysteries, a Social Darwinist, and an explorer of sub-Saharan Africa), and Nietzsche. The constructions of Ambler’s early novels, from The Dark Frontier (1936) to A Coffin for Dimitrios (1939)—the most celebrated work of his pre-War career—established a stylistic pattern and a set of themes that are consonant with Frye’s taxonomy of literary forms. With its exposure of dark doings under Stalinism, Judgment on Deltchev may not seem to be an easy candidate for Frygean analysis, but Frye’s generic categories offer a relevant entry point into this novel’s convoluted plot line. According to Frye, “[m]yth . . . is one extreme of literary design; naturalism is the other, and in between lies the whole area of romance” (p. 136).

Ambler’s complex plotting falls under the Frye’s idea of “design,” for it doesn’t just fulfill the conventions of the suspense thriller, but manipulates suspense so as to produce abortive epiphanies in reader and chief protagonist alike. These epiphanies are triggered by the discovery of shocking truths about human nature and the sinister world of political intrigue. ‘Romance’ is the appropriate generic category for Ambler’s narratives of discovery insofar as his protagonists are not malign agents, useful idiots, or mere pawns of intelligence agencies, but everyday democratic personae; and insofar as his plots center on a quest for justice or truth, or for some sort of redeeming indication that humanity is capable of digging itself out of the horrors of twentieth century history.

Mythic Conflict

While riddled with irony and awash in ambiguity and desperation, Ambler’s fictions do tend to end with demonic forces held at bay, and this is in keeping with Frye’s conclusions. “[P]opular fiction,” Frye writes, “is realistic enough to be plausible in its incidents and yet romantic enough to be a ‘good story’, which means a clearly designed one” (p. 139). Myths are cosmic fictions structured around the struggle of gods and demons, the forces of the good pitted against the minions of evil. The romantic or romance mode tends “to suggest implicit mythical patterns in a world more closely associated with human experience” (pp. 139-40). Ambler’s worlds are highly unromantic, but insofar as he takes readers into mysterious cultural or political territory, and navigates his detective heroes through conspiracies, dangers, and cliff-hanger scenarios, he is writing within the broad stream of the romance mode.

Poplar genres such as the twentieth century suspense thriller and the spy or crime story present world-pictures, that is, images of contemporary history, which are subject to idealization (romance) or to irony (realism) according to the author’s sensibility and/or the demands of the market audience. Frye’s “mythical pattern” in which angels and devils battle each other in visible and invisible worlds (i.e., heaven and earth) is reinscribed by Ambler onto a Cold War stage setting, where titans such as the United States and the Soviet Union are locked in ideological combat and covert actions of all sorts.

Myth is a projection of the divine “categories of reality” (Frye’s phrase, p. 141); realism is a representation of human categories of reality, i.e., reality as configured by the senses and organized according to the laws of human consciousness. Romance is the middle term between myth and realism, ideally a kind of Hegelian dialectic synthesis in which the moral promises of myth win out, but also vulnerable to the tragic or ironic catastrophes of the world of the real, that is, to the universe of death. While death, in the form of murder, has a central place in Ambler’s fictional world, he opts to limit his body counts and prefers an impending sense of danger or doom to unrestrained violence and demise. This tells us that he seeks thematic resolutions on the plane of romance rather than leave his readers stranded in a bleak world of sheer ironic absurdism. But this seeking after romance—which is often concentrated in the survival and moral enlightenment of the unvanquished protagonist—is also relentlessly demystified.

The Metaphysics of Crime

In the ironic or absurdist ethos that prevails in so much twentieth century modernism one doesn’t find much room for portrayals of romance realized. In the aftermath of Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud, who eviscerated humanistic values and evicted God from the universe, romantic fulfilment proves rare for the modern hero. In fact, this figure enjoys little of the grandeur or social standing of the heroes of old, and is more often than not a troubled member of the bourgeoisie or the downtrodden working class—an anti-hero. Ambler’s protagonists are not, for the most part, professional spies or police detectives, but middle class Westerners who get entangled in intrigues and find themselves borne away on a quest that undercuts the promises of conventional romance. Stumbling across crimes and conspiracies, they work to determine the secret infrastructures of time and human nature. The characters that they run up against represent the dark forces that drive public events.

In this way, Ambler proves to be a vanguard author in the history of the thriller. International politics, he reveals, is a treacherous business and the inner workings of civilization, whether western or eastern, are barbarous. Behind the doubts and discoveries that drive the plots, perennial themes of myth and philosophy loom up in a troubling, modern guise. A Coffin for Dimitrios, for example, begins in the following manner:

A Frenchman named Chamfort, who should have known better, once said that chance was a nickname for Providence.

It is one of those convenient, question-begging aphorisms, coined to discredit the unpleasant truth that chance plays an important, if not predominant, part in human affairs. Yet it was not entirely inexcusable. Inevitably, chance does occasionally operate with a sort of fumbling coherence readily mistakable for the workings of a self-conscious Providence.

The story of Dimitrios Makropoulos is an example of this.

The fact that a man like Latimer should so much as learn of the existence of a man like Dimitrios is alone grotesque. That he should actually see the dead body of Dimitrios, that he should spend weeks that he could ill afford probing into the man’s shadowy history, and that he should ultimately find himself in the position of owing his life to a criminal’s odd taste in interior decoration are breath-taking in their absurdity.

Yet, when these facts are seen side by side with the other facts in the case, it is difficult not to become lost in superstitious awe. Their very absurdity seems to prohibit the use of the words ‘chance’ and ‘coincidence’. For the sceptic there remains only one consolation: if there should be such a thing as a superhuman Law, it is administered with a sub-human inefficiency. The choice of Latimer as its instrument could have been made only by an idiot.

During the first fifteen years of his adult life, Charles Latimer became a lecturer in political economy at a minor English university . . .

Ambler’s protagonists are concerned with uncovering wrong-doing and political villainy, but the characters that they encounter, and the revelations of self and of human nature that come their way, raise questions that go beyond the immediate topicalities of setting and history. Ambler turns popular fiction into a platform for querying the human struggle with chance and destiny, the hidden weave of history, the pathos of existence, and so on. In this way, Ambler’s fiction, centered on its ordinary-man protagonists, addresses what the critic Ronald Ambrosetti terms the “metaphysical homelessness” of the modern self (Eric Ambler, pp. 137-8).

This striking term—“metaphysical homelessness”—names a spiritual malaise known to modern literature and existential philosophy. Such homelessness is expressed in the novels of Dostoevsky, Conrad, and Kafka, and the poetry of T.S. Eliot. In philosophy it is addressed in the form of the old existence vs. essence imbroglio, as presented by Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, and several other thinkers and writers of that type. Touching back to the opening of Ambler’s Dimitrios, the big question is do events run randomly and for no good purpose, or is there a hidden gospel truth that cuts through the labyrinthine, idiotic-seeming weave of history and promises to bring all souls to salvation in the New Jerusalem? This is the Kierkegaardian either/or that festers in the psychic life of Western civilization, particularly after the anti-clericalism of the French Revolution, the ascendancy of Marxism in economic and political affairs, and the Death-of-God prophecy proclaimed by Nietzsche’s madman in the marketplace. One need hardly adduce the horrors of the twentieth century, with its fascist death camps and its Stalinist gulags, to underline how real and pressing the riddle is.

Western modernity has fallen prey to its own paradoxical project: the attempt to organize society on moral principles whose metaphysical foundation has crumbled. And yet there is no alternative; societies must be built out of something higher than mere material interests. They must be organized around transcendental values, whether these are grounded in the old faith narratives or in their secularized derivations (e.g., democracy and philosophical liberalism, human rights, social justice). The first half of the twentieth century was traumatized by ideologies—imperialism, ethnic nationalism, fascism, Marxist-Leninism—whose application was meant to subordinate or utterly replace the faith systems and historical myths that once ensured social cohesion. But this experiment came at a bitter cost; for when ideology is imposed on actuality (as Marx and Lenin demanded), combustion occurs. On the individual level, metaphysical homelessness is an acute dilemma for those afflicted by its irresolvable questions. Does humanity as a species and the individual as a soul subsist as a fixed archetype in the mind of God or are we randomly dispersed chaff on the wayward winds of interstellar space? Absurdists and modernists take these to be rhetorical alternatives and assume the latter option. But this leaves modern man and woman in a dire predicament, struggling with bleak, dispiriting questions: solitary, and cold, and forlorn—is that what the entire history of modernity teaches? Is that our condition and are our lives but as witlessly real as a bubble on the purpling lips of a fresh corpse?

Nietzsche was the philosopher who detested democracy, sought a new scale of values beyond “Christian slave morality” (his phrasing), extolled the “will to power,” and exhorted the übermensch to rise up in the absence of a dead God. At the same time, he railed against the pathetic, moralistically and materialistically petty “last men” who survived the superstructural cataclysms that Nietzsche prophesied and welcomed. Is Yordan Deltchev the muddled, Marxist version of such a “last man”? Judgment on Deltchev carries an epigraph from Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra (1885):

Many things in your good people cause me disgust, and, verily, not their evil. I would that they had a madness by which they succumbed, like this pale criminal!

The novel is built around the spectacle of a Stalinist-style show trial in which Deltchev speaks less and less as the story progresses and indeed fades from view as an assassination plot comes to dominate the narrative. If Deltchev approaches the condition of Nietzsche’s pale criminal, it is not because he is unambiguously culpable of any misdeed—the narrative doesn’t clearly implicate Deltchev or establish his place in the assassination scenario. It is rather his failed ‘goodness’ that’s on trial, or, more to the point, the ambivalence of his political ‘evil’-doing, which leaves him vulnerable to his cut-throat rivals and to the subversive undertakings of his wife and children. His ‘guilt’ is such that he never took his own deeds far enough; his political ambition fell short.

It is in this sense that he fulfills the criteria of Nietzsche’s pale criminal, a figure whose courage to kill was a mere momentary fit of madness (as the remainder of the section from Zarathustra bears out). By lapsing into the autism of moral remorse, or sacrificially covering for his family’s conspiracy against the state, Deltchev pronounces judgment on himself; he falls silent in the dock and begins to look Socratic in his suffering. Such is the determination made by Foster, the novel’s first-person narrator. But the epigraph from Nietzsche belongs, perhaps, to Ambler, not Foster, so that we are meant to appreciate the tension that this novel, like so many others by Ambler, stages in theme and narrative design: the juxtaposition of chance and providence, of dialectics (Socrates and sleuthing) and romantic despair (Nietzsche and metaphysical homelessness).

Politics: Primordial and Modern

In the development of espionage fiction, Ambler’s stories occupy a pivotal place. His hero is effectively an amateur, but in trailing terrorists and criminals he gets involved with bureaucrats and government agents, and looks ahead to the post-World War Two spy as presented by Ian Fleming (the James Bond stories), John Le Carré and several others: the professional spook, the man who occupies a niche in the intelligence hierarchy of the modern state. Judgment on Deltchev exhibits this kind of overlap, as it takes us into a factional conspiracy played out within the structures of a Stalinist regime. The novel casts an initially self-deceived Western eye (the protagonist’s) upon the internal machinations of Balkan nationalism and communist governance. Topically, its setting is the Cold War and the immediately preceding fascist and interwar period. But Ambler also leverages his narrative into themes that are as old as Plato’s dialogues and Greek drama: the struggle between the primordial, pre-political unit known as the family, the clan, the tribe, and the impersonal institutions of the modern state built around an apparatus of laws and sovereign functions.

The dialectic tangle of conspiracies in the novel stems from a fundamental opposition between the reactionary Officer Corps Brotherhood and the “progressive” ideology of a Soviet satellite in eastern Europe, presumably Bulgaria. This opposition, which pits the blood ties of the old nation against the bureaucratic ideologues of the People’s Party, is as old as the struggle between Antigone and Creon in the last play of the Oedipus trilogy. The secret pledge that swears loyalty to the Brotherhood invokes “Kindred Families,” “Sacred Motherland,” “Birth”, and “blood” in an oath unto death (chapter xii, pp. 154-5 in the Vintage Crime edition; henceforth styled as xii.154-5). The flight from such an oath and the internal struggle with such reactionary allegiances is what tortured Deltchev throughout his political career and his rise as a member of the Agrarian Socialists faction.

When Foster closes out the story in a newsreel screening facility in London, he frames Deltchev’s execution in light of Plato’s Crito, where Socrates reflects that “the difficulty is not to flee from death, but from guilt. Guilt is swifter than death” (xxi.275). Condemned to die, Socrates attributes the “guilt” of his demise to his accusers and judges, but in Deltchev’s case the guilt is his own by a kind of ironic proxy. The trial proceedings are illegitimately stacked against him. That much is certain. But it is in the shadow of sanguinary nationalism (the Brotherhood) and kinship that he is being tried. The guilt he cannot fly from is his in the sense that it is under his family name, in the persons of his wife, son, and daughter, that a plot was laid to assassinate Petra Vukashin, the sinister People’s Party leader and head of state.

Setting aside Deltchev’s personal motives, which are suggestively and ambiguously Nietzschean (according to the “pale criminal” epigraph), there is the bigger sweep of history to consider. “Papa” Deltchev’s surprising acquiescence before the unjust sham of a typical Stalinist show trial has long been inexplicable. But now, at novel’s end, we realize that Ambler’s narrative has inverted the logic of Plato’s Crito by placing Deltchev in a liminal position. His political affiliations are murky and his innocence is questionable. He is trapped in space of dialectic tension, not unlike that which structures Sophocles’s Antigone, according to Hegel. Deltchev’s fate brings this ancient tension into view—the friction or collision between political demands grounded in kinship bonds and organic affiliation (today we would call this identity or bio-politics, as grounded in race, ethnicity, ‘culture’, or even gender) and those that appeal to the rule of law and the ideologically defined state (i.e., statecraft that claims to transcend particularities and grounds itself in constitutional norms).

The modern state, in other words, styles itself in the overarching image of the Freudian super-ego, supposedly establishing clarity and reason in place of the chthonic, primitive realm of the family unit, which is likened to the id and its demands; and yet, as Freud himself observed, the super-ego is surreptitiously linked to its lower origins since the entire psyche was once unconscious and subsisting at the level of the id. So it is with the Deltchev family, with the ideological masks it wears and its troubled place in the nation’s political history.

Intertextual references to Plato and Nietzsche, but also to actual Eastern bloc historical actors, deepen our assessment of Yordan Deltchev’s political positioning within Ambler’s narrative design, as well as our assessment of Foster’s world-view, which is also part of that design. Deltchev’s career shows him rising and then falling as he succumbs to treacherous political enemies, and in this sense he is a would-be tragic hero. In classical or Shakespearean tragedy these enemies would have been fate or the gods, or nefarious Machiavellian-like enemies of an otherwise noble “high mimetic” society. In this case, the source of fatalism is modern politics itself, and a particular historico-ideological form of politics: Marxist-Leninism.

Following Frye’s modal categories, we can say that Foster’s world-view is ironically mythical. His ideological outlook falls to one side of the great Manichean split that distinguished West from East during the rising Cold War. We need to remind ourselves (if we didn’t recognize it already) that Frye’s five modes and phases of literature actually form a cycle, a circular economy that repeats and mutates throughout cultural history. In other words, the oldest myths and archetypes may and do reappear in Ambler’s novel, but under the sign of modernist irony and satire. We have already noted how Ambler deploys the archetypal romantic quest of the hero on his liminal adventure. Foster enters the political ‘hell’ of a closed, Stalinist society. So what is it that furnishes the mythic framework in Ambler’s vision? The answer to this is self-evident: a demonic political doctrine. Hanging behind Ambler’s dystopian satire of a Cold War eastern bloc country is a visio malefica (a vision of evil). The evil in this case is the Bolshevism.

Ambler conceals his archetypes of good and evil by wrapping them in irony and parodic satire. Parody is a type of imitative mockery of something else: a kind of ironic counter-mimesis, as the original Greek word para-oidia implies. (There are, of course, degrees of parody from the overtly polemic to the blank or non-committal forms so dear to absurdist and postmodernists.) And so we can run through a list in which Yordan Deltchev is the parody of an innocent person and his trial is the parody of justice. At the same time, aspects of the West are satirized in the person of Georghi Pashik, for Pashik, as we will see, is the parody of an American. Yet the role of Pashik in this text reminds us of Frye’s claim that mythical modes and symbols express the summit of human desire. Even as he undercuts Pashik’s pro-Americanism, Ambler presents communism as the parody of a paradise on earth. And in this way Ambler delivers an unmistakable verdict on the ideological enemy of the West during the early Cold War.

Fact and Fiction

Ambler assiduously blends fictional and factual history. Deltchev’s distressing political fortunes echo the fate of real figures from Balkan politics of the late 1940s. The novel’s first chapter ensures that we learn of Bulgaria’s Nikolai Petkov and Romania’s Julius (Iuliu) Maniu and Ion Mihalache (i.7). Petlarov, one of Deltchev’s former associates and a fictional figure, later mentions Jozsef Mindszenty, a Hungarian Catholic Cardinal who fell afoul of the country’s communists. Mindszenty’s conviction and prison sentence serve as an allusive reference point for Deltchev’s misfortunes before the court. Despite the fraudulence of the show trial, Foster starts to suspect that Deltchev’s innocence may not be a foregone conclusion. The realization is brought on by Petlarov’s suggestion that the court may be working with shreds of sound evidence against the accused, and that “[t]he lie stands most securely on a pinpoint of truth” (v.56).

What Ambler’s narrator or his interlocutors don’t need to invoke are facts that would have been tacitly understood by anyone discussing recent Balkan politics. Namely, that Petkov had been a leading member of the anti-Nazi Fatherland Front, an agrarian organization that formed Bulgaria`s first post-Nazi government; or that as an anti-communist Petkov was targeted in a home-grown Stalinist show trial, and was executed in September 1947. Mindszenty, whom Petlarov mentions twice (the second instance is at vi.71), was subject to a show trial in February 1949. At the end of that same year, Traycho Kostov, a real figure in Bulgarian political life who nevertheless goes unmentioned in the novel, stood in the dock at yet another show trial, charged with for “Titoist nationalism” and pre-World War Two fascist collaboration.

These concrete historical episodes help establish a hypothetical date for the novel’s action, which would seem to occur in either 1949 or ‘50. But Ambler takes advantage of poetic licence, for if the assassination of Brankovitch occurs on Saturday, the fifteenth of June (see xiv.171), then the year of the novel’s action must be 1947 according to the Eastern Orthodox Julian calendar. In the more widely used Western, Gregorian calendar that same date could only fall in the years 1946 or 1957. These, however, are immaterial to our critical reception of the text, and far more significant is the résumé of Deltchev’s rise and fall, which likens him to Petkov and Kostov especially, and gives his final silence a quixotic resonance.

Chapters three and four outline Deltchev’s career. In the interwar period he served as a lawyer and rose to become Minister of Posts and Telegraphs. It was during this historical interlude that he emerged as a shrewd, understated figure within the Agrarian Socialist Party and probably cultivated surreptitious ties with the Officer Corps Brotherhood. When his country fell in line as a Nazi satellite state in 1940, Deltchev was interned. By 1943 he began to organize a low-key anti-German movement and assisted in founding the Committee of National Unity, which resulted in the formation of a Provisional Government in the Spring of 1944. Deltchev acted as that government’s foreign minister, reaching out for Anglo-American support as Germany fell back on the eastern front and the Soviets prepared to overrun the Balkans. In the postwar period Deltchev made an unexpected move: instead of retaining power with the Provisional Government, he took to the radio and issued a surprise election call. Why he did so is never divulged by Foster, who learns the reasons for this in his last interview with Madame Deltchev.

The Big Unknown

This lacuna concerning the novel’s titular figure is of exceeding significance. Because of Deltchev’s unaccounted announcement, the People’s Party stages a successful coup near the election date (iii.24) and his political demise is then conclusively sealed when he denounces the Party in football stadium address. In this sense the lacuna is an expository matter, but it also acts rhetorically as an aporia, or philosophical enigma. It creates a kind of suspense trope prolonged over the course of the entire narrative. From it flow all of Foster’s initial and ultimate misjudgments and his reflexive animosity toward Vukashin and the rival People’s Party.

Around this deliberately employed lacuna/aporia, which concludes Foster’s final visit with Madame Deltchev, Ambler devises his title and constructs the entire novel as one long string of speculations about the accused man’s motives for not retaining power. The show trial begins with a sunken, grey-haired prematurely aged figure facing his accusers and from this point onward the novel goes on to offer a steady diet of speculative or incomplete judgments about his personal and political character.

He is, according to Pashik’s file, a man of honest reputation, a man who cannot be tempted (iii.24). During his early rise the common people were wont to see him as a self-sacrificing patriot directly inspired by God (iii.28). Petlarov, who was once his secretary and friend, and possibly a distant rival for Madame Deltchev’s affections, says he is a good man, but self-critical and not at ease with himself (v.54-55). Madame Deltchev herself describes her husband as a man of reason not feeling (vii. 86). During his eerie meeting with ‘Valmo’, who is really the cold blooded hit man Aleko, Foster starts to suspect that Deltchev was indeed complicit with the Brotherhood (x.129). In one of Foster’s meeting with Madame Deltchev, he stumbles into possibility that Deltchev is a “fool” (xiv.181). In the end we view the mysteriously-motivated martyr as a pale criminal, or an avatar of Socrates, or both.

Ambler’s narrative design runs on a double track. The moral question at the heart of the story—what is the degree of Deltchev’s culpability?—becomes a concentric issue around which the assassination conspiracy—the main ingredient of the suspense plot—is steadily exposited, becoming ever more complex as the action proceeds. For Western readers in Ambler’s time, Deltchev’s show trial could only remind them of the all-too-familiar intimidation tactics practiced by governments against internal enemies. This includes Stalinist regimes, to be sure, but perhaps even HUAC or Senator McCarthy on the Western side of the Iron Curtain. Is Deltchev the false bull’s eye? What is the real nature of the conspiracy? Who controls the killers and who is the intended victim? Is the Vukashin regime staging a trial behind which it has hijacked a plot and is turning it against its own internal opponents?

The Democratic Persona

At the climax of the novel’s assassination plot, in which Vukashin’s agent Aleko kills Brankovitch, the government’s propaganda minister, Foster cries out lines from the New Testament and America’s founding political documents. But the inexorable march of doom is not staved off by citing the words of Christ, or the US Constitution or Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence.

I began desperately to try to reassure myself. It just could not be! I had been listening to the babblings of a lunatic. Or—better, far better!—the verdict of Passaic and Oakland and Hagerstown had been that those things which were God’s should be rendered unto God, that—Article-something-or-other-of-the-Constiuion-of-the-United-States-of-America—nobody can do anything that affects the life, liberty, or person of anybody, without the aforesaid democratic procedure having been properly and faithfully observed, and that the best thing Georghi Pashik could do would be to move his fat arse the hell out of it and send that suit to the cleaner’s. (xx.262-3)

It is likely that at this point of maximum suspense Ambler wanted to highlight Foster’s paradoxical function as a democratic persona, a subject formed under the civil and moral regimes of the West, who nevertheless takes on sardonic airs toward his malodorous, east European handler Georghi Pashik, a man that turned his back on communism and the Brotherhood, and who wallows haplessly in pro-American pipe dreams. Foster’s desperate outburst in the moments before the assassination tells us how deep his cultural prejudices run and where his Cold War allegiances lie, consciously and subconsciously.

Ambler himself, a moderately left-leaning figure in the Thirties, had soured on communism and Stalinism following the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, and reports of life and politics in the post-Hitler eastern bloc only increased his ideological alienation (in this, he resembles somewhat George Orwell’s position in the Forties). Ambler’s autobiography makes note of the left-of-centre friends whose affection he lost after Judgment on Deltchev was published. Ambler’s drift from the left affected the unfolding of Foster’s point of view as we experience it in the reading process. The outward nature of the villainy he is faced with is self-evident (Stalinism of the local colour variety), but none of the actors stay predictably on script. Foster’s initial smugness toward the show trial is justifiable, but his struggle for genuine insight into the calculations and duplicities of the Eastern actors reflects the many unknowns that complicated Western intelligence analysis. Ambler is undoubtedly critical of the leftist totalitarian state, yet he also exposes the ideological ‘ethnocentrism’ of the democratic self who fails to appreciate the ingenuity of the ‘other’s’ evil.

It is easy to denounce wholesale the evils of the Stalinist state and claim to see through its propaganda, but it’s much more difficult to construct an actionable picture of the enemy’s operations and plans. Such is the challenge of espionage and detection, which the novel brings into popular consciousness via Foster’s first-person viewpoint. Despite his subtle disparagement of Pashik’s American lifestyle fantasies, Foster remains conditioned by Western values of liberalism and democracy, and as such acts as the reader’s ideological compass. But like the readers of the nineteen fifties, and perhaps like the intelligence agencies themselves, he has much to learn.

The Bolshevik Legacy

Judgment on Deltchev reflects a consensus that was emerging, at the time of its publication, among disabused pro-leftists in the West. Appearing only two years after Nineteen eighty-Four, Ambler’s novel presented a time-specific, realistic variation on the Orwellian socialist dystopia. Rather than opting to project the author’s ideological distaste into a hopeless and fearful totalitarian future, it drew on the everyday news cycle and allowed Stalinism to discredit itself in the present. There is no need for an Emmanuel Goldstein character or some sort of capitalist, Western villain (Foster can hardly be that) to justify the Stalinist state’s internal abuses. In several of his previous fictions Ambler had addressed the violability of borders and sovereignty by showing how domestic affairs are susceptible to transnational forces. In Judgment on Deltchev he presented a country sealed behind the Iron Curtain, undergoing an ideological experiment in which a new form of power (communism, socialism) is imposed on a state with a residual nationalist foundation that is characteristically fascist in tone.

Such is the novel’s Hegelian dialectic already mentioned above, which harkens back to Sophocles’s Antigone, but adds a uniquely Marxist-Stalinist twist: the Brotherhood (the national family as a primordial political unit) struggles fruitlessly against the People’s Party (the modern political unit as defined by ideological blocs such as “the working class”), while the People’s Party undertakes a savage purging of its erstwhile ideological partners, the Agrarian Socialists. Ambler illustrates how a false socialist utopia is capable of undermining itself, without the meddling or the intrigues of foreign capitalists (Pashik’s and Yordan Deltchev’s contacts with the Anglo-Americans are not direct threats to the People’s Party regime). With this conception guiding the novel’s construction, Ambler represents the legacy of Bolshevik sectarianism working itself out well past the date of Lenin’s or Trotsky’s demise.

Bolshevism promised to start history over again, but its viability as a political vision had always been compromised by murderous internal splits or the relapse into manipulations of nationalism, an option that wasn’t beyond Stalin, as John Lewis Gaddis points out when looking back on the Cold War in 1994:

Stalin was, above all else, a Great Russian nationalist, a characteristic very much amplified by his non-Russian origins. His ambitions followed those of the old princes of Muscovy, with their determination to gather in and to dominate surrounding lands. That Stalin cloaked this goal within an ideology of proletarian internationalism ought not conceal its real origins and character: Stalin’s most influential role models, as his most perceptive biographer, Robert C. Tucker, has now made clear, were not Lenin, or even Marx, but Peter the Great and ultimately Ivan the Terrible. (“The Tragedy of Cold War History,” Foreign Affairs, Jan.-Feb. 1994, pp. 144-5)

The truth of this observation is seen in Madame Deltchev’s revelation that Brankovitch, the state’s chief of propaganda, who was scheming to murder Vukashin, would have tried to consolidate power with the help of the Brotherhood, an unmistakably nationalist movement. In the grim circumstances of their final meeting, as political chaos swirls outside the walls of her Ottoman-era compound, she remains calm but dejectedly tells Foster that “we could have come to terms with Brankovitch” (xx.269).

The Mysterious Madame Deltchev

In the closing dialogue between Foster and Madame Deltchev his attraction to her gives way to a conclusive disdain. Brankovitch has been gunned down after Vukashin subverted the Brotherhood and took over the assassination plot. Foster thinks he can run off to Athens, where the surviving son Philip Deltchev has absconded, and get Philip’s signature on an official expose of Vukashin’s nefarious machinations. Pro-Western Greece was a pivotal factor behind the formulation of the Truman Doctrine of 1947 and would gain NATO membership in 1952. Foster enters ‘Bulgaria’ from Yugoslavia and leaves via Greece, which he intends to make the staging ground for a political truth that will resound around the Western world and discredit its Cold War enemies. But Madame Deltchev, who is herself Greek, lives under the long, seemingly invulnerable shadow of totalitarianism and empire: she survived the Nazi occupation and is now subject to house arrest in a high-walled compound whose architecture tells of centuries of Ottoman imperialism.

She may be guiltier than her husband, and perhaps the greater “criminal” in that sense, but she is right to rebuke Foster for his ideological blindness. When he imagines that Philip’s sworn testimony in Athens can then rapidly be disseminated in Paris, London, and New York, thus bringing down international opprobrium on Vukashin and his allies in Moscow, she cuts him short. Foster, the playwright, seems to be enthralled by the possibility of turning Brankovitch’s death (a factional crime) and Deltchev’s impending execution (a judicial crime) into a kind of Cold War romance scenario. Madame Deltchev smartly upbraids him for holding, uncritically, to the democratic myth that transparency can resolve all political and moral conundrums.

“My dear Herr Foster,” she said wearily, “do you suppose that you can defeat men like Vukashin with external propaganda? The conception is naïve.” (xx.269)

Shortly thereafter, the chapter finishes with Foster’s arrival in Athens, followed his flat, toneless observation that Vukashin has liquidated Alexander Gatin (‘Aleko’) and Pashik, and his discovery that Philip is a “pompous but amiable young man” who awaits his mother’s arrival but says nothing about his father’s impending execution (xx.271).

The Smell of Symbolism

Of the four major characters whose quadrature forms the armature of the novel—Foster, Yordan Deltchev, Madame Deltchev, and Pashik—it is this last figure that remains to be assessed. Pashik is, in several senses, a partial reflection of each of the other three. He was once a partisan of the ultra-nationalist Brotherhood, then transmuted into a traitor and a spy, an ostensible propaganda lackey of the regime, an ally of Madame Deltchev’s, a party to the most secret homicidal intrigues of the state, and, finally, a would-be Westerner who romanticizes the United States. In the end, he dies for having miscalculated Vukashin’s ruthlessness, and after making the same mistaken assumption that Foster labours under—that ‘truth’ in the service of Western propaganda can undermine Stalinism (xiv.255).

We first meet Pashik as a press facilitator for Foster, who arrives in Sofia (or so we presume) as a journalist unfavourable to the People’s Party regime. Pashik arranges for Foster’s accreditation and secures the necessary permits with the police and the appropriate ministries (Interior, and Propaganda). Through the several peripeties of their professional relationship, Pashik begins to emerge as a complex, pathos-ridden figure, part comic, part tragic. Near the end of the novel we get an astonishing insight into Pashik’s soul: the collage of American movie starlets and magazine clippings that paper the walls of the sitting room in his apartment. It is a dizzying pastiche of American popular culture and consumerism in the age of the Marshall Plan. “There was no wit, no hint of social criticism, in the arrangements . . . . It was fantastic” (xvii.209). Pashik’s photo still of Myrna Loy, which Foster noted in the Pan-Eurasian Press office (ii.16), is here complemented by Ann Sheridan, Betty Grable, and “[a] gauze-veiled brunette with a man’s bedroom slipper in her hand” (xvii.209).

This revelation of Pashik’s American obsession and his girlie pin-ups is facilitated by Sibley, an English journalist who repeatedly tries to befriend Foster and intrude into his reporting assignment. Sibley is, as one critic suggested, a homosexual character, but this is not the central to his role in the plot. A former serviceman in British military intelligence, Sibley’s function is to exposit Pashik’s nomadic past. From Sibley we learn that Pashik is yet another in Ambler’s fictional catalogue of cultural and ideological crossbreeds.

Pashik was born in Trentino, Northern Italy, of Macedonian Greek parents. He did military service in Austria; worked as journalist in Paris and Rome; married an Italian wife who soon died, after which Mussolini’s fascist regime expelled him from Italy in 1937. It was under the influence of fascism that he secretly embraced the cause of the Officer Corps Brotherhood. But when German troops marched in and took over his country in 1940, Pashik’s press qualifications and expertise in languages landed him in Cairo, and then in Beirut where he worked as an interpreter for British and American forces. This assignment also involved intelligence work on behalf of his Western employers, and he was well positioned to return to Bulgaria and Macedonia in 1944, where he operated as Deltchev’s interpreter for negotiations that the latter was holding with the Anglo-Americans. Having adopted an American worldview while in Lebanon, serving under a certain Lieutenant Kromak (who muses idyllically about home life in New Jersey), Pashik than began betraying the Brotherhood; as a secret informer he ensured that its members were steadily picked off. His dreams of emigrating to the U.S. unfulfilled, Pashik stayed in Bulgaria and functioned as a regime mouthpiece by running the Pan-Eurasian Press Service, in which he holds 49% shares, the other owner being Madame Deltchev at 51%.

All of this is back-story. When Foster starts his narrative we meet Pashik as an unlikely “man of destiny” (ii.12). He is described as short, dark, thick-necked, bespectacled, physically flabby, and malodorous. He carries a revolver and a “stale meat sandwich” in his dispatch case, and drives a “battered Opel” (ii.12-13). Pashik, however, proves to be less of a stereotype than Foster first imagined. In fact, he ‘reads’ Foster’s character before Foster reads his. In the run-up to Deltchev’s ideologically rigged trial Pashik informs Foster that it was bound to look “dramatisch,” that is, “theatrical” to “Western ways of thinking (ii.19). On day one of the trial he warns Foster against the tendency of viewing it in mythical terms as essentially, a “spiritual conflict” (iv.45). But well before he begins to awaken from his own dogmatic slumbers (nearly dying in the process), Foster waves away the cautionary words and focuses instead on the bearer of such telling admonitions.

Under Foster’s prim, English perspective, Pashik is a chronically unwashed specimen from the Balkan boundaries of the orient. He is indeed as pan-Eurasian as a European could be. But he has also learned to speak English with an American accent and wears a much-travelled American-made seersucker suit from a Houston department store (xvii.221). Foster makes much of the fountain pens that adorn Pashik’s sartorial image, for they come from Passaic, New Jersey, a kind of vicarious locus amoenus that the latter will never visit. Like the body odour that Foster remarks at several points, the pens are symbolic tokens of Pashik’s aspirations. A symbol is an image with a conceptual dimension. As defined by the English Romantic writer Samuel Taylor Coleridge, a literary symbol is the kind of trope that combines the finite or the concrete, with the infinite or the metaphysical. Any sensory object, event, or entity can function as a symbol provided that it sparks a higher train of associations in and through its physical properties.

The fountain pens from Passaic are for Pashik magical objects; they are saturated with ideals and fantasies; their otherwise commonplace objectivity brings him into palpable contact with a near-mythical America. So does the seersucker suit, which we learn is a gift received while serving in Germany under Colonel McCready, whom Pashik saw—in Sibley’s jocular phrasing—as the “last of the prophets” (xvii.221). Pashik’s physical smell is more symbolically profound, for its repeated invocation points to a fate that he will never transcend: his odour is not only a personal, physiological condition, but the very mark of his ethnicity and fate; it signifies the dismal inescapability of his cultural predicament and the destiny that awaits him in the totalitarian East.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link