by Theodore Dalrymple (September 2024)

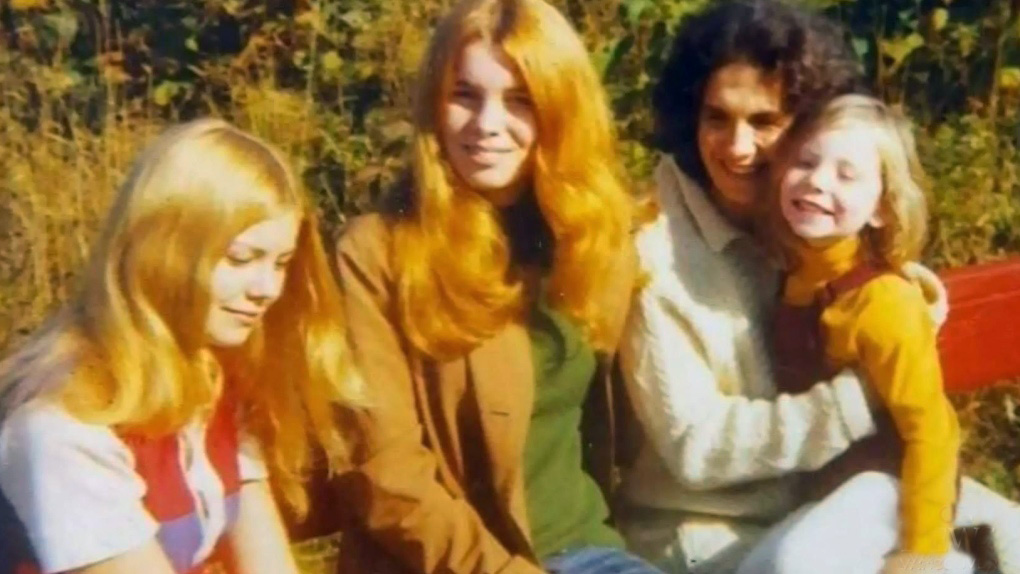

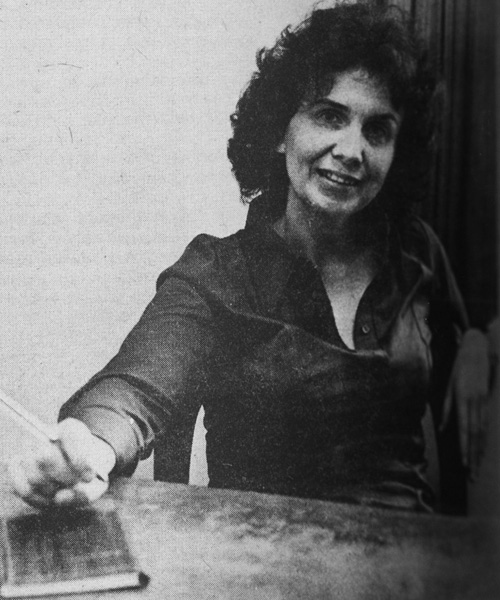

The revelation that Alice Munro, the widely-revered Nobel Prize winning Canadian author of short stories, more or less connived at the persistent sexual abuse of her daughter by her second husband is very startling. The revelation was made by her daughter, Andrea Skinner, in an article published recently in the Toronto Star, and the allegation is not of the he-says-she-says variety, but more than well-founded.

One of the reasons the revelation is so startling is that Munro herself, explaining her choice of small-town Ontario life as the subject of her stories said:

There are no such things as big and little subjects. The major things, the evils, that exist in the world have a direct relationship to the evil that exists around a dining room table when people are doing things to each other.

She said this well after she knew about her second husband’s abuse of her daughter. The most charitable interpretation one could put on this was that she was suffering at the time from a severe case of cognitive dissonance, the mental state of having inconsistent thoughts, none of which can be given up without discomfort. In fact, this is the interpretation I prefer, because the alternatives are too horrible to contemplate: not, of course, that this makes it true.

Her daughter recalled Alice Munro blaming the misogynistic culture for what some would perceive to be her own shortcomings:

(My mother said) “our misogynistic culture was to blame if I expected her to deny her own needs, sacrifice for her children, and make up for the failings of men.”

The meaning of this passage is not absolutely clear, but it seems to imply that her mother believed her failure wasn’t really her own—that she was, in effect, a victim herself, a feather in the wind of a bad, misogynistic culture.

To suppose that Alice believed she was simply a product of her cultural circumstances—she the author of many books and the recipient of a Nobel Prize! —is simply preposterous: but if it were true, it would mean that she was not a fully adult member of the human race, responsible for what she did or failed to do.

But who, then, would be those fully responsible adults? The monstrous regiment of misogynists, who made it impossible for her to forego living with her second husband or to sacrifice her relationship for the sake of her children? Again, this seems pretty preposterous. Neither individuals nor groups of individuals formed into vigilante groups to prevent mothers such as Alice Munro from leaving their abusive second husbands can be found. At least in the circles in which Alice Munro moved, surely there would have been no social pressure for her to behave as she did: if anything, the reverse.

To blame misogynistic culture for the less-than-ideal behaviour of women is to give women a get-out-of-gaol free card, at the cost of turning them in creatures so weak and feeble that they themselves can do no wrong through their own agency. To blame Alice Munro for her choice would be like blaming a dog for eating a sausage that it has found. Eating sausages is what dogs do, if given the chance; not being able to leave child-abusing second husbands is only to be expected of women, for like Luther, they can do no other. This attitude, surely, is true misogyny, though in this case it is self-hating misogyny.

Let us not be too harsh and try to exert understanding. Love has its reasons which reason knows not of. It is a powerful bond. Many people fall in love with persons who are completely unworthy of their love. I think, in my career as a doctor, I must have seen hundreds, if not thousands, of such cases: so many, in fact, that I began to fear the snares of love itself. I came across many women who loved almost self-evidently monstrous men but had great difficulty breaking themselves free of them. The difficulty was not institutional but emotional, for eventually they did break free of them (sometimes, alas, to find another such man), and therefore, from the point of view of the choices available to them, could have done so before. The abuse that they suffered at the hands of these men sometimes beggared description and even imagination, but an infinite number of excuses could always be found by the women to preserve their relationship (the dullest intellect is a genius when it comes to finding excuses). There was no shortage of abusive women either, though their abuse was usually of a more subtle kind, poison rather than poniard.

When every allowance has been made, however, no one would think more highly of Alice Munro for what at the very least was weakness of will.

There is an interesting and perhaps unresolvable question of how far knowledge of the life should affect the estimation of the work. One of the great writers of prose in English in the twentieth century, for example, was Arthur Koestler, but his reputation was damaged, if not permanently (one can never say for ever), then for decades, since revelations that he was sexually predatory and may even have resorted to rape or near-rape. When the private letters of Philip Larkin were published, that revealed that he was a crude racist, his reputation suffered, though it was overwhelmingly as a poet that he was celebrated, and there is no reason why a good poet should not have bad ideas (as most of us have on some subject or other). The discovery that V.S. Naipaul, another Nobel prize-winner, was cruel, unfeeling and violent towards women, which he admitted with something approaching relish, understandably damaged his reputation as a man of the greatest moral and artistic probity. It is difficult to now read his books without this biographical knowledge constantly intruding from the back of one’s mind, though perhaps in time the awareness of his bad character will fade.

Of course, the kind of revelations that damage an artist’s reputation change both in time and with the passage of time. What is historically recent is more harshly judged than what happened a long time ago: we forgive Caravaggio his murder. What we consider beyond the pale changes too. The case of the French writer, Gabriel Matzneff, is a case in point.

He had a coterie of admirers, among them the late President Mitterand. Much of his subject matter was the sexual relations that he, a mature man, had with adolescent girls and even young boys in the Philippines. He published diaries of his relations with young girls, in books apparently admired by some for their style. He made a joke as late as 1990 of his relations with such young girls on a popular television programme devoted to literary matters and when the Canadian journalist and writer, the late Denise Bombardier, took him to task as an abuser, she was treated by everyone in the studio, not just by Matzneff, as a provincial unsophisticate. But with the publication of a memoir by the publisher, Vanessa Springora, in January 2020, recounting what would now be regarded at the very least as disgusting exploitation of a young girl, Matzneff’s reputation collapsed completely, to the extent that even second-hand copies of his books became difficult to obtain online. But if they were ever any good from the literary point of view (having read one or two, I was not myself of this opinion), they would still be just as good as ever they were.

It would be most interesting to see whether the revelations about Alice Munro’s conduct have any effect on the sales of her books. They might have no effect whatever, of course, either because people chose to ignore the revelations or because they did not have wide enough circulation. They might put people off buying the work of a person too weak to support her own daughter when she needed such support, placing her own emotional needs above hers, or they might increase curiosity, or prurience, and hence sales. Only time will tell, though I doubt that anyone will waste his time researching this question.

But now I want to turn to Alice Munro’s suggestion that there are no big or little subjects, which means that there are only subjects. She backs this up by contending further that:

The major things, the evils, that exist in the world have a direct relationship to the evil that exists around a dining room table…

This in turn suggests that evil is not only a subject of writing and literature, but the subject of writing and literature. And this view, which I quite often catch myself sharing, is no doubt the result of an awareness of the terrible catastrophes of the twentieth century. How can any serious person spend his mental energy on lesser subjects, or writing pure comedies, when millions of people—scores of millions, hundreds of millions—have been killed in the most terrible circumstances. And just as charity begins at home, so does evil. Evil begins at home—even, I am tempted to say, in Canada.

What is huge evil but small evil writ large? And it is true that evil is not to be measured on a simple linear scale. We would not say that the slaughter of two million people was twice as bad, morally, as the slaughter of one million, though it might lead to more suffering because it is more extensive. This being the case, we might be tempted to say that the domestic tyrant is as bad as the tyrant of an entire country, the difference being not so much in the content of their heart but in the scope of their reach, which is to a large extent a matter of chance. Therefore, what Alice Munro said was essentially correct.

And yet this seems absurd. A domestic tyrant may be a very good man outside the walls of his domicile, just as a political tyrant may be an excellent father, husband and son within his. We should hardly regard them as equivalent, though, even if the nastiness of their hearts were of the same depth.

On the basis that evil is the subject of subjects (and there is not denying its attractions as such), all thought, all scholarship, all writing, about anything else would be frivolous. There is a puritanism about those who make evil their subject, as if the study of, say, the early postage stamps of the Cape Colony were an evasion of responsibility, a kind of displacement activity of the soul. A mouse confronted or cornered inescapably by a cat washes its paws, to distract itself (assuming it has sufficient consciousness to need distracting) from its imminent personal disaster, We humans choose subjects—shall we say football or arguments over the reality of male and female—to avoid having to confront the evil by which we are surrounds and which awaits us so threateningly.

I have been fortunate. I have seen a lot of evil in my time and have even sought it out. I have witnessed cruelty, injustice, viciousness, ruinous dishonesty, and almost unbelievable malignity: but I have never suffered from any myself. No one has ever oppressed me, taken away my liberty, or even merely insulted me, other than fleetingly. I have been left to make my own terrible mistakes, which is one definition of the free man: his misfortunes are of his own making. Sometimes, I even feel mildly guilty that I have been so fortunate: I doubt that much more than one per cent of the world’s population has been as fortunate as I. While I would not go so far as to say I had absolutely no hand in making my own good fortune, honesty compels me to admit that chance had a major, of not the major, part in it. My problem is that, not being religious, I do not know who to thank for it. If the answer is returned, ‘God’, then in logic all those who suffer unmerited misfortune (and they are many, even some who seem to attract unmerited misfortune as a magnet attracts iron filings) ought to blame Him. I accept, however, that those who believe in the existence of a divine providence are better able, psychologically, to withstand misfortune.

The question of evil continues to haunt me, however, perhaps for family reasons. All four of my grandparents were refugees, my mother was a refugee, my mother’s sister was a refugee twice by the age of forty-two. They all suffered incomparably more than I; by comparison with them, my path through life has been that of a hot knife through butter. I do not believe in cosmic justice.

Table of Contents

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest books are Neither Trumpets nor Violins (with Kenneth Francis and Samuel Hux) and Ramses: A Memoir from New English Review Press.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

6 Responses

Most of Alice Munro’s short stories are formulaic. She resorts to the cheap thrill for the reader’s attention — typically, someone is attending to a mundane task in life, which is interrupted by a huge reveal: For ex:

In 15 years he had only once missed watering the grave of his daughter: the sound of the water filling the tub reminded him of his son who drowned in the family swimming pool. And then we learn how they get on their their lives. Given what we now know of Alice in Iwonderland, I suppose it’s a classic case of transference. That her characters manage to get on with their lives is what she wishes for herself. The recurring plot technique, like a recurring nightmare, suggests that she didn’t manage as well as she would have liked — and of course there are better than good reasons for this.

Hmmmm….

I find myself unusual in that I seem not to care at all what someone gets up to in their private life, if I like the work I like the work.

Caravaggio, per his wikipedia page, seems to have been a chronic violent boor, of the street thug type, although also wearing a sword as if a gentleman, which he technically appears not to have been, in an age when both street thugs and gentlemen routinely engaged in lethal interpersonal violence over slights small and great, real or imagined. That the younger man he was known to have killed was of the same type, and likely a member of a more formal criminal gang, seems to me to be sufficient justification. I appreciate it was legally murder, but then in most jurisdictions so was killing a man in a duel, and those also were fair fights voluntarily engaged in. It was for the authorities of Rome to dispose of, but centuries later I can’t imagine why I, consumer of his work, need to forgive him for anything.

Not necessarily founded on the same exact judgment, but my reaction to the works of Naipaul or Koestler is similar- if I find value in the work, what do I care of the personal qualities of the men?

It is a little different for politicians and officials- these take oaths, and their actions can have public consequences. Even then, though, a politician is not a source of moral guidance, and what free man would consider taking such guidance or needing it? Do what I want and don’t do what I don’t want, and a politician goes far to winning my tolerance. I will tolerate less from him than an author, given his official and public role.

Whereas an author, meh.

If they gained fame solely as moralist and memoirist, then the inconsistency of their preaching and life might be relevant.

In Matzneff’s case, for example, the subject matter of his work connects that work to the moral questions of his life in a way not necessarily the case with the other examples.

For Munro, were I interested in her work I would still be. Some of the public moralizing she did, however, comes across a little different now.

Munro’s behavior seems to validate Helene Deutsch’s contention that passivity and masochism are two of the main psychological characteristics of women.

Thank you for your observations and insights including the Blaise Pascal citation paraphrase.

We all have a bifurcation of psyche. At least I observe that in myself.

“The heart has its reasons which reason knows nothing of… We know the truth not only by the reason, but by the heart.” – Blaise Pascal