Fashionable Fascism

by Rebecca Bynum (November 2009)

The Third Reich in the Ivory Tower: Complicity and Conflict on American Campuses

by Stephen H. Norwood

Cambridge University Press, 2009

This was not antisemitism on violent display as in Nazi Germany; it lay beneath the surface, unspoken, but it allowed the leaders of these elite institutions to downplay the anti-Jewish policies and atrocities that were clearly occurring in Nazi Germany throughout the 1930’s. These prestigious Universities ignored the purging of Jewish professors, the segregation of Jewish students, the burning of Jewish books and the Nazification of education in general and continued to act as if nothing untoward were happening in Germany that should interfere with normal scholarly relations.

Illustrating this attitude well is a speech given by Dean Virginia C. Gildersleeve of Barnard College in April 1933. She “labeled the situation in the Third Reich ‘disconcerting’ but urged her audience not to judge Germany by American standards. The outlook and behavior of an ‘alien’ people might appear eccentric but if Americans knew ‘the circumstances in which seemingly unreasonable actions take place, those actions would seem reasonable.’ Gildersleeve concluded: ‘Perhaps if we knew more of the facts we could understand what the German people are feeling and trying and wanting to do.’”

Of course, the trouble with the Nazi movement was our own lack of tolerance and understanding toward it: we should simply have acquiesced to Germany’s “legitimate aspirations.” Even more ridiculous, but every bit as reminiscent of our own time, was a speech given by University of Berlin Professor Friedrich Schoenemann at Vassar entitled, “The New Democracy in Hitler’s Germany.” In it, “Professor Schoenemann compared the Nazi takeover in Germany with the American Revolution and explained that ‘at bottom [Hitler] is a democrat.’ Schoenemann claimed that reports of Nazi atrocities against Jews were false, ‘invented purely for propaganda purposes.’ He claimed that Jews led the Communist movement and at the same time dominated ‘all the money-making professions in Berlin.’ Schoenemann denounced Albert Einstein for not ‘suspend[ing] his judgment’ about the Hitler government ‘until he knew the facts.’”

Professor Schoenemann had been shouted down “with laughter, hisses and shouts of liar” by the average people of Boston when he spoke at the Ford Hall Forum on Beacon Hill. Anti-Nazi protests against him were so vehement that it turned Beacon Hill into a battle zone. Mounted police finally drove the protesters, estimated at between 3,000 and 5,000, many carrying banners which read, “Down with the Nazi Butcher” and “Down with Hitler” down “the steep slopes of Beacon Hill, chasing them a half-mile through the streets and ‘smashing heads right and left.’ The demonstrators ‘fighting every inch of the way,’ pulled some policemen off their horses and pummeled them. Police reinforcements finally ‘lifted the siege of Beacon Hill.’” However, at Vassar, Schoenemann received a quiet and respectful hearing by the impressionable young women and their professors.

The University of Virginia, Institute of Public Affairs periodically held roundtable conferences in which they seemed to go out of their way to provide a forum for the German antisemitic point of view, hosting American antisemites like William J. Cameron as well as German propagandists like Friedrich E. Auhagen, who was arrested as a Nazi agent and deported after the war. At the 1939 conference held less than two months before the German invasion of Poland, Manfred Zapp, New York representative of the Transocean News Service of Berlin, “delivered a vitriolic anti-Semitic address in which he proclaimed his ardent support for Nazi Germany. He began by condemning the ‘one-sided’ American press coverage of Germany, which falsely reported that in the Third Reich ‘the individual has no freedom.’ Germans actually had ‘just as much freedom as…in other countries, if not more.’ Unlike in the West, where the rich could buy more liberties than were granted the poor,’ each individual in Germany had an equal amount. The Germans had forged a national community, a true ‘people’s state,’ unlike parliamentary democracies which were actually ruled by ‘demagogue politicians.’ Under the Weimar Republic, Germans were divided by class antagonisms and feared for their safety. Night clubs featuring ‘nudism and sex’ proliferated, undermining the country’s moral fabric.

“Zapp declared that during the Weimar period a corrosive ‘Jewish influence…became more and more predominant in business and politics.’ By ‘preaching freedom of the press, freedom of speech, and freedom of the individual’ the Jews ‘sowed discontent among the German people,’ fomenting divisions that resulted in twenty-eight different political parties bickering in the Reichstag. Exploiting the chaos they had fomented, the Jews seized control of the nation.

“According to Zapp, the Nazi movement arose to liberate Germany from the Jewish-induced decay. It sprang from ‘German sentiment,’ grew ‘on German soil,’ and was ‘made for Germans and Germany only.’ Hitler had restored labor harmony and full employment. Under Nazism, prosperity had returned to Germany, and slums had disappeared.”

“According to Zapp, the Nazi movement arose to liberate Germany from the Jewish-induced decay. It sprang from ‘German sentiment,’ grew ‘on German soil,’ and was ‘made for Germans and Germany only.’ Hitler had restored labor harmony and full employment. Under Nazism, prosperity had returned to Germany, and slums had disappeared.”

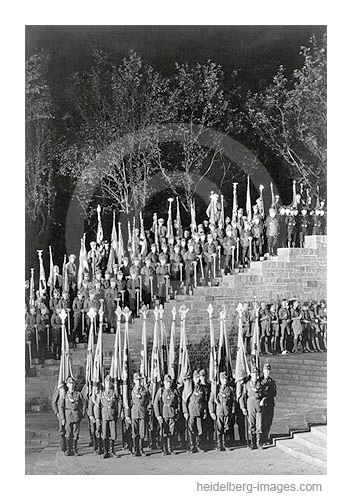

Of the American student newspapers, only the Columbia Spectator mounted any serious opposition to the school administrations’ policies. Both the Harvard Crimson and the Yale Daily News towed the official line of fascist sympathy. Columbia’s President, Nicholas Murray Butler (winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931), took the extraordinary step of expelling a student for organizing a protest against Columbia for sending a delegate to the Nazified University of Heidelberg for its 550th anniversary. Goebbels used the occasion to stage the usual brownshirted propaganda pageant.

Though he had turned his back on the Jewish refugee scholars during the 1930’s, during the last year of Conant’s Presidency at Harvard, he hired the former Nazi nuclear physicist, Carl Friedrich von Weizsaecker to teach there. Von Weizsaecker had been deeply involved in the push for the Nazi atomic bomb. After leaving Harvard in 1953, Conant became the American Ambassador to West Germany where he pressed for the early release of imprisoned Nazi war criminals. In 1950, 3,649 of the most hardened Nazis were being held by the Allies. By January 1955, 3,300 had been released. By June of that year the U.S. held only 42 remaining war criminals.

Though he had turned his back on the Jewish refugee scholars during the 1930’s, during the last year of Conant’s Presidency at Harvard, he hired the former Nazi nuclear physicist, Carl Friedrich von Weizsaecker to teach there. Von Weizsaecker had been deeply involved in the push for the Nazi atomic bomb. After leaving Harvard in 1953, Conant became the American Ambassador to West Germany where he pressed for the early release of imprisoned Nazi war criminals. In 1950, 3,649 of the most hardened Nazis were being held by the Allies. By January 1955, 3,300 had been released. By June of that year the U.S. held only 42 remaining war criminals.

Among those Conant advocated for was Josef “Sepp” Dietrich, a man as deeply involved with the Nazi movement as it was possible to be. He had been with Hitler since the earliest days before the Munich Putsch. He was a street brawler and Hitler’s first driver/bodyguard. He acted as head of Hitler’s bodyguard in the early years before Heinrich Himmler took over and it became the elite SS. Hitler placed Dietrich in the Waffen SS and eventually used him to take over a panzer division during the Battle of the Bulge. There, Dietrich massacred American prisoners of war. He was convicted at Nuremberg for his part in the “Night of the Long Knives.”

Dietrich died of natural causes at his home in Ludwigsburg in 1966 at the age of 73. Seven thousand of his wartime comrades came to his funeral. He was eulogized by former SS-Obergruppenführer and General of the Waffen-SS, Wilhelm Bittrich.

Ambassador Conant also approved the release of Konstantin von Neurath, formerly Hitler’s foreign minister and Reich’s protector of Bohemia and Moravia, after he had served only eight years. Von Neurath returned home to a hero’s welcome, complete with strewn flowers and church bells. Conant also helped to parole Joachim Peiper who had engaged in the sadistic burning of Russian villages on the eastern front during the war.

After stepping down as West German Ambassador, Conant gave a series of lectures at Harvard in which he maintained that “persons who had not lived in a totalitarian society had no right to condemn the German people for their behavior when Hitler was in power” and that most of them were never “real” Nazis. Which means as little as the current academic contention that Muslims do not “really” believe in Islam, after all, most academics don’t “really” believe in anything and wouldn’t be caught dead with a firm conviction.

William L. Shirer, on the other hand, declared in a lecture at Boston’s Ford Hall Forum in 1961 that Adenauer’s Foreign Ministry was “shot through and through with Nazis” and that a Nazi past, no matter how horrendous, was no handicap to advancement in West Germany – which, of course, was the simple, honest truth. Something that had evaded the learned men of academia.

Professor Norwood’s book should be assigned in every college in America. It is structured to allow easy comprehension – the beginning of the chapter gives an outline of the material to be presented, the evidence is then then laid out in an orderly, dry fashion, and then a conclusion re-caps and summarizes the evidence, making it easy to understand and to retain.

Though it is not covered in Norwood’s book, there is no doubt that academics in Germany quickly acquiesced to the Nazification of education. In America today there is evidence of acquiescence to the Islamization of education on all levels, from the insertion of Islam into the elementary and secondary textbooks, to the overwhelming support for the suppression of freedom of expression in the Universities.

To comment on this article, please click here.

If you have enjoyed this article, and would like to read more by Rebecca Bynum, click here.

Rebecca Bynum contributes regularly to The Iconoclast, our Community Blog. Click