by Kenneth Francis (September 2023)

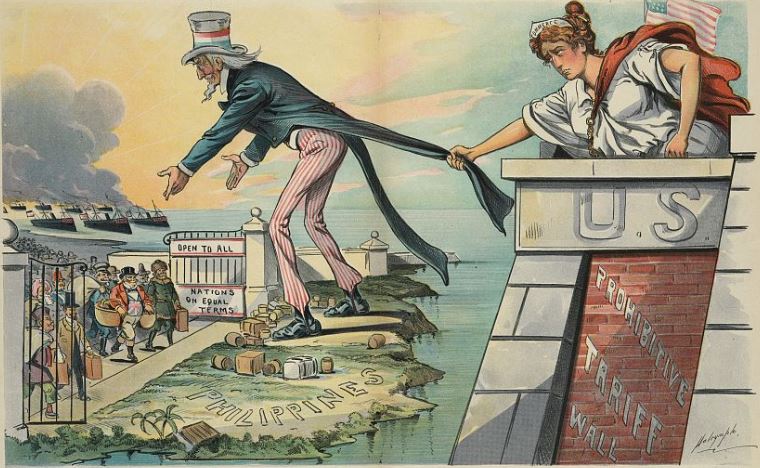

Charity Begins at Home, Louis Dalrymple, 1898

The words, “Easy to be Hard,” in the title of this article refer to the name of a song from the 1968 Broadway rock musical, Hair. “Easy to be Hard” was also covered in 1969 by the band, Three Dog Night. The lyrics are quite interesting and psychologically highly perceptive:

How can people be so heartless

How can people be so cruel

Easy to be hard

Easy to be cold

How can people have no feelings

How can they ignore their friends

Easy to be proud

Easy to say no

Especially people who care about strangers

Care about evil and social injustice

Do you only care about the bleeding crowd

How about a needing friend?

The song was written during a time of great unrest in 1960s America, during the Vietnam war, the Draft, Sexual Revolution, the ethnic disintegration of cities, and disaffected youth. It is about rebellious, anti-war Hippies in New York City, in particular a young woman called Sheila, who is upset that her ideologically driven boyfriend (Berger) seems to care more about ‘bleeding crowd’ strangers who are in need, as well as self-interested social injustices, while Sheila’s needs are ignored or secondary.

The last verse of the song is very telling. You probably recognised some of these people at some point in your life. I certainly have met many of them and still do. They are sometimes referred to as social justice warriors (SJWs) or Woke activists. This makes one wonder: Were these people damaged psychologically as a child, deprived of intimate love, and cannot seem to bond to an individual and love him or her before caring about strangers or distant causes? If that is true, bonding more with an ideology or the needs of the ‘in-crowd’ seem to explain their detachment for those closer to home.

In reaching out to remote causes, they feel proud of themselves by virtue-signalling and championing the ‘Other,’ as well as being less responsible for the feelings or welfare of an individual friend. For care and loyalty of the individual loved one or friend, is to metaphorically ‘enter through the narrow gate,’ as opposed to the easier-to-enter ‘wide gate’ favoured by the mass in-crowd (Matthew 7:13-14).

One of the many negative traits associated with these SJWs is they are full of pride with deep-seated convictions. Is it any wonder that the deep State sees these useful idiots as model citizens who are easy to control. In WB Yeats’s poem, “The Second Coming,” he writes: “…The best lack all convictions, while the worst are full of passionate intensity…” The reason for this is because SJWs have replaced God for the deep nanny-State, which tells them how to think.

The Christian philosopher JP Moreland once told a story of when he was a young student and had “a thing” for a girl at college but she was more interested in fighting for some other “bigger” cause; probably an anti-war movement during the Vietnam conflict in the mid-1960s. Intimacy with fellow-student Mr Moreland or embracing God was not for her. This is because the SJW craves moral reputation from the herd and a craving to be popular.

The Bible says: “Be careful not to display your righteousness merely to be seen by people. Otherwise, you have no reward with your Father in Heaven. 6:2 Thus whenever you do charitable giving, do not blow a trumpet before you, as the hypocrites do in synagogues and on streets so that people will praise them.” (Matthew 6:1-2)

In the past in literature, we see other, similar-type SJW characters, as in Dickens’s “Bleak House,” where Mrs Jellyby, an English “telescopic philanthropist,” is more concerned and obsessed with an obscure African tribe but having no regard for charity beginning with her own husband and family who struggle to survive, while her house lies in ruins.

In fact, the current hijacked West has metaphorically become “Bleak House,” with ‘Mrs Jellyby’ political leaders, who seem to treat their own indigenous citizens with contempt and are more focused on representing other causes in foreign lands, even at the expense of their own people. This self-centred “philanthropic” insanity is certainly not done through love or kindness.

In 2016, Philanthropy Daily journalist, Jacqueline Pfeffer Merrill, wrote: “Dickens’ critique of telescopic philanthropy is likewise germane today, when Americans give $15 billion [*See latest figure below] annually to global causes. Of course, many of these causes are very worthy, but we must be thoughtful about balancing global causes and urgent needs in our own neighbourhoods and country, and about whether we understand the needs of far-away people well enough to do good. So far, Dickens’ time and ours were alike.” [*Since the war began, the Biden administration and the U.S. Congress have directed more than $75 billion in assistance to Ukraine. Meanwhile, Maui is reduced to ashes, while its citizens are crying out for aid].

Pfeffer Merrill is right about many causes being worthy, but the key issue is prioritising concerns closer to one’s own ‘home.’ Consider ‘telescope philanthropy’ in Ireland: Integration Green Party coalition Minister, Roderic O’Gorman, announced Ireland’s soft-touch asylum policy online in eight different languages. The tweets were posted in February of 2021, and they outlined the government’s plan to end Direct Provision and provide “own-door” accommodation to any and all asylum seekers in Ireland after just a few months. They were posted in English, Irish, Arabic, Georgian, Albanian, Somalian, Urdu, and French. Meanwhile, thousands of indigenous Irish homeless people live on the streets in tents, and over 100,000 Irish children and young people are on hospital waiting lists, according to the National Treatment Purchase Fund. Such telescopic philanthropy inviting the Third World to come and be housed in Ireland for free would make even Mrs Jellyby blush.

This is what happens when one rebels against the Logos. In his short story, “Things That Fly,” Douglas Coupland seems to have a remedy: “… I need God to help me love, as I seem beyond being able to love.”

But most SJWs hate the God of Christianity. A couple of years ago, Black Lives Matter activists cornered a woman at a restaurant in Washington DC because she wouldn’t raise her fist in solidarity with their chants that “white silence is violence.” One of the protesters in front accusingly asks, “Are you a Christian?”

Finally, charity should begin at home (if the members of that home are not deviant idiots), avoid SJWs, who obviously need God to help them love intimately, as they reach out to save and help strangers or perpetuate doomed, woke causes in faraway lands. Many of them might end their days alone or super-glued to a painting at the local art gallery, or disrupting a sporting event by streaking around a football pitch with “Just Stop Oil” tattooed to the cheeks of their rear end. Love them, be kind to them, but to repeat, avoid the Greenpeace warriors, as they arrive wearing face masks and lay candles and teddy bears on the sand when a dead Orca is washed ashore with a face-mask stuck in his blowhole. SJWs should instead spare a thought for the unfairly demonised, caucasion heterosexual males—not the killer whales.

Table of Contents

Kenneth Francis is a Contributing Editor at New English Review. For the past 30 years, he has worked as an editor in various publications, as well as a university lecturer in journalism. He also holds an MA in Theology and is the author of The Little Book of God, Mind, Cosmos and Truth (St Pauls Publishing) and, most recently, The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Theodore Dalrymple) and Neither Trumpets Nor Violins (with Theodore Dalrymple and Samuel Hux).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link