by Justin Wong (November 2019)

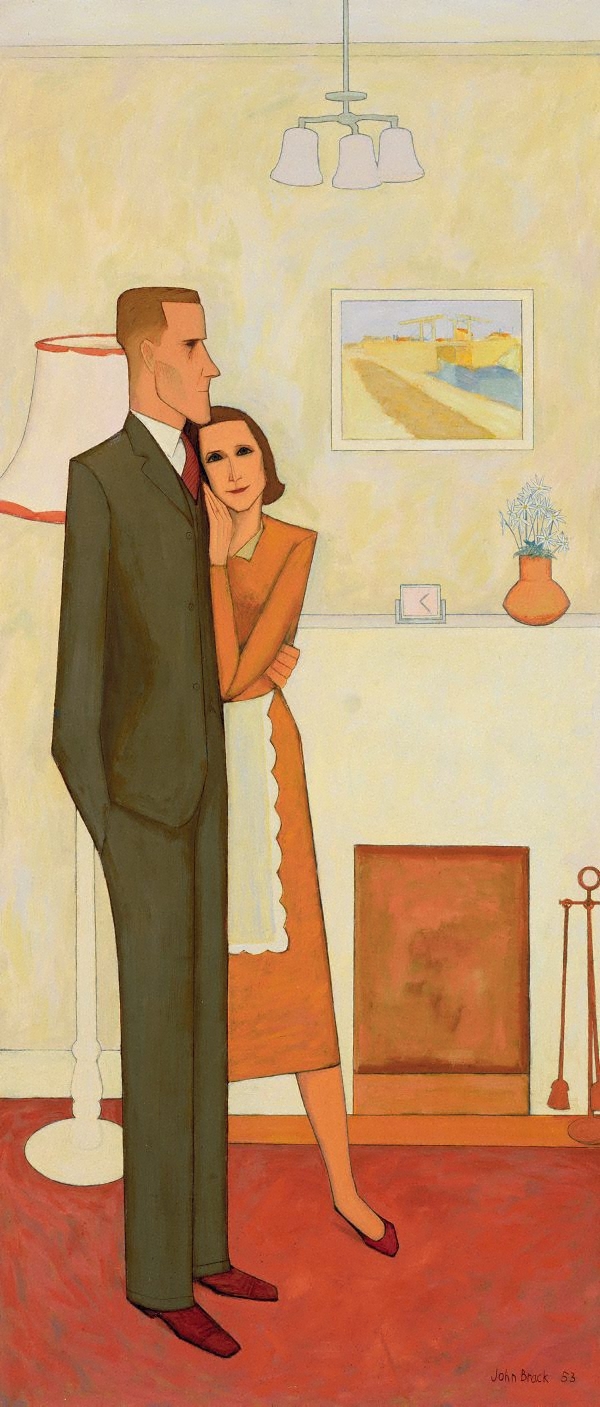

The New House, John Brack, 1953

One of the most common misconceptions that parents almost universally have, is that other people’s children are superior to their own. Though this often says more about human nature than the children, in the belief that better things are always to be found elsewhere, outside of one’s own lot.

Mary certainly felt this way about her son Jack whom she adored. Everything that she did in life was said to be for him—the meals she strenuously cooked, the work that she and her husband did, and the house was made to be a stable environment where he could thrive. All of her free time was dedicated to the rearing and flourishing of her child. There were clearly things about him that she found most troubling—one could say disappointing—he was quiet, preferred the company of himself, and was caught up in his own world, often one of make believe. Such things made Mary worry for her child, and she wondered if this behaviour, the one of being a loner whose mind was caught up in fancy, would cast him off as something of an outsider, someone who found it difficult to bond and make companions with other children of his age, and she wondered if this always being alone when in the house translated to the classroom, or to the playground, where this behaviour carried on albeit in a different atmosphere. Thinking back to her days in school, as long ago as this now seemed, she remembered there being children like her son, those who seemed apart from everyone else, who never seemed to fit into the groups that most people naturally formed, and as a consequence were viewed as being odd, strange, laughable, scorned. In her youthful days when she was the same as her now eight-year-old son, she remembered a girl in her class called Shelly, a girl who was chastised by almost everyone in the class, someone who never seemed to be a part of a clique, who smelled as if she rarely washed, if at all, and who everyone seemed to hold in contempt. Though her idiosyncratic acts, that of eating insects as a kind of performance art, of her not brushing her hair, and her being ugly didn’t perhaps help her cause.

Despite these obvious fears that crept into her mind, whatever troubles young Jack had they weren’t half so bad as the girl she knew when growing up, and though he was someone who liked to do things by himself, in a room and alone scarcely made him into a social outcast of this degree, and looking at him with objectivity, he was handsome, who was daily washed and went to school wearing clean, crisp shirts, and was the most smartly dressed among all the others in his class. He was hardly what anyone would call unpopular, and more than a half dozen times he had been invited to parties, though there was no one child he was really close with and there was rarely anyone who could play with him.

Mary wondered to herself at times if this behaviour was all her fault, which wasn’t her being irrational in that she and her husband waited and left it too long having children. There was adequate reason for her thinking this, as Jack was an only child and, by the time they had met and married, she was in her mid-thirties, someone who was very much in the closing act of her fertility. Now she was well into her forties. Thus, young Jack would have to grow up without a sibling and spoilt, he would have to live his life as an only child, without there being anything in the way of camaraderie that is found when you are amongst others who are born of the same parents. She wondered if this—the fact that he had no siblings—made him a social outcast. When one has someone who is born to the same parents of similar age, it helps the child bond with others. Seeing as Jack was alone, he had not this understanding, and perhaps couldn’t form relations, learn to share, and compromise as the other kids could when left out in the world and by themselves.

Now he was eight years old. This wasn’t the first time these worries diseased the mind of Mary and, in Jack’s more formative years, there were other things that came to pass which frightened her, though such stresses faded to a non-existence when she read up on them or when she consulted specialists. The main thing was that he had imaginary friends. Years ago his closest companions were people that weren’t real and, though she heard of other children having such fantasies, other children conversing with things that weren’t apart of reality, she was scared at what all this meant, and that this show was the first signs of what was a serious disorder, a psychosis. Her mind wondered with this and, above all of the things that she blamed, she blamed herself. How could I be so foolish?, she thought to herself; having children so late in the day, it was inevitable that such things would occur. Though the more she read up on this condition—for lack of a better word—the more she found this was a harmless thing that many children go through, a thing that is rather cute when one thinks of it.

She still felt concerned for young Jack regardless of his imaginary companions, and she tried to compensate for the fact that she had him towards the end of her fertility window (and thus condemned him to a fraction of a life as an only child, where his prospects might be limited for anything in the way of intimacy) by taking him to many social events—places where he could meet others the same age as him, to form bonds and make close companions. Though there were friends he made, these friendships often didn’t take off and, though he got to know other children, these arrangements felt as if forced and they were very much the result of his mother being friends with the mother of a child, rather than any deep bond the child and Jack felt.

Mary wondered to herself if all this was something that was an issue solely in her head, and seeing as he wasn’t really crying out for the presence of others, and seemed often quite content when she checked on him and he was daydreaming, on the floor, staring up at the ceiling as if looking at phantoms or unseen things. His room as it was, was spacious and, seeing as there were no others in the house aside from him and his parents, he had a big vast enclosure to himself a place that could quite easily house two children of a similar size, in bunk beds, or beds side by side. There were always toys scattered about the room, numerous pieces of molded plastic was to be found in chests, on the shelves in his room, and the walls were decorated with images of things he loved, posters of his favourite superheroes, characters from cartoons he enjoyed, such that he watched on Saturday mornings. One could say all of this, the room filled with material possessions where an outsider peering in, could quite easily surmise that he was one of those children who was given all he wanted, where all his desires for boyish things were most evidently fulfilled. His parents, in satisfying his every desire and his love of fantasy, cartoon heroes, of books set not on this planet, of things that are make believe, probably went a long way in exciting his imagination, where he desired not the void and lonely house he lived in and came home to on afternoons, but relished the worlds of wish fulfillment in the juvenile shows he watched, in the books he read.

Mary ceased to worry about this for some time and one day, when Jack was at play in the house running through it wearing a cape, when his mind was lost in an alternate reality, thinking of saving the day with his super powers, she noticed something in his hand. A toy she had never seen before.

“Jack, what is that son?” pointing to the anomaly contained in his hand, which was a toy truck something he showed little interest in, and something she couldn’t for the life of her remember buying.

“It’s a truck, Mummy,” he said being blasé about the whole thing, “It’s my friend Andy’s, he said I could borrow it.”

“Really, your friend, and where did you meet him?”

“At school. He sits next to me during science.”

“I’m glad. I’d really like to meet him sometime.”

She was glad to hear of this, that her son, the boy who to her was always frightfully alone, was starting to develop a social life, that he wasn’t the lonesome daydreamer she always knew him to be, and was getting out there and making connections with others. When she told her husband of what he said, of him having a friend, he advised her to get in contact with the boy’s mum to arrange a time when they could get together after school, when they could play with each other.

The next day, when she was waiting to pick her son up outside the gates of the school, there was the usual gathering of parents who congregated there, some of these mothers she knew, and spoke with whenever she happened to run into them. Though it wasn’t too long until the final bell was rung, when it was audible to Mary and the others who stood standing outside, and all that was needed now was to wait, till all the kids poured out the building, running to their Mother’s or guardians that were stood there, as if they had just escaped from a beast who held them captive, desiring to run towards a realm of safety.

As Jack ran towards her, he hugged her as if they had been separated not for the six or so hours they had spent apart, but as if he had been away for her for weeks. Though Mary wished to know all of what she told him of the previous day, meaning the new friend he spoke of, mentioning his name briefly the day before.

“So, where is Andy?” she asked, and with this he scanned the roads that were becoming crowded, with ever more children that were making their way out of the gates. Though he managed to fish him out of the increasing multitude, and pointed her in the direction of where his friend stood. He was next to his Mum, and she was standing there, straightening out the scruffy appearance of her son, tucking his shirt in his trousers, and straightening out his collar.

She walked over to him, and his mother.

“Hi,” she said, “are you Andy’s Mum?”

“Yes,” she said.

“My son Jack has told me that they are friends.”

“Oh really, you’re friends with Jack?”

“Yes, he’s a good guy.”

“Yes, I was just wondering if Andy wants to come over some time, to the house, so they can play with each other?”

“Oh yes, that’s very kind of you,” she said, “How does that sound, Andy, do you want to go over to his house to play with him?”

He nodded at this, whilst smiling.

“Well, good you can come over on Thursday. If you’re free, I will pick you up after school.”

“How about that Andy? You can go and play with your friend after school on Thursday.”

When Thursday came she managed to pick them up, and driving them around the streets, she managed to talk with him a bit, and grew curious as to him, it was evident from his Mother in the unusual way she dressed, and the nut brown complexion of his skin, that his family most probably didn’t originate from England.

“So where are your parents from?” she asked him, hoping not to sound too interfering.

“Oh, my family came from Egypt,” he said.

“Really, wow that’s interesting. And your name is Andy.”

“Well, that’s what people call me at school. My real name, what my parents call me, is Amin,” he said.

“Well, that’s interesting, and you know, my family comes from Ireland, and some of Jack’s Dad’s family come from here and Jamaica,” she said. “You know, Jack’s an only child, do you have any brothers of sisters.”

“Yes, I have three sisters,” he said, “They’re all older than me.”

“Wow, that must mean you have a busy house!”

“Yes, it’s four women against two men, you know I’m quite outnumbered,” he said.

Mary, hearing this, giggled to herself at a boy of her son’s age who was so articulate, who was good at talking with adults, and seemed to know so much.

When they arrived home, Mary made them both a snack and, after Jack showed his friend his room and his collection of toys that he amassed, they came down again. Mary was standing in the kitchen preparing for them a dinner which she said would be ready for them in an hour. And, after they had a drink of juice, Jack suggested that they play video games on the computer console.

“I have racing, this spider game, football,” he said.

“Yes, that’s great, if it is okay with you Mrs. Gas?”

“Of course, you can, and please just call me Mary,” she said, of course charmed by all this display—the sight of a boy who seemed as socialised and at ease in the company of adults as he was with her son, who above all things seemed intelligent, mature, and worldly in a way in which her son, if one was permitted to speak freely, was not. Upon seeing and conversing with her son’s newly made friend, she thought that all the fears she had—the apprehensions that having an only child was a mistake—was the correct line of thinking. She thought Jack may have fared better if he, like his friend, had grown up amid the influence of numerous siblings, where such things as manners and social skills rubbed off from observing others close by, and where he was able to absorb such standards as a sweat-filled shirt.

They seemed to get along well, and spent the afternoon as it veered slowly into the evening, in the company of each other. For a few hours, they managed to play on the games console in the living room, sitting down close in front of the vast television that had been set up. Mary, whilst she was cooking, managed to hear the sounds in the kitchen from the living room of the television, the repetitive and child-like music, the sound effects from the game. Explosions went off and chime-like sounds that were otherwise heard in casinos could be faintly perceived in the distance.

After a while, after food she was preparing from within the kitchen was cooked, she called them over to the dinner table to the meal of fish, chips and peas. Digging into the meal, they both ate with the desire for food of the malnourished, stopping only for the ketchup bottle or a sip of coke from their glasses.

“This is beautiful, Mrs. Gas,” he said.

“Oh, really, you like it?” she said, partly flattered. “It’s just one of my usual meals.”

“It’s so delicious.”

“Well, Jack prefers his grandmother’s cooking, don’t you?”

“This is good too.” Jack said, though felt somewhat that this was an attack on his ingratitude. It seemed to him that she was taken with this new companion of his, and his mind wondered with this, that these first impressions that she got from him, made it seem that she preferred his company, with all the flattery and praise he gave to her.

It wasn’t a long time until the meal, the one his friend Andy spoke of in such exalted tones of, was over, and the plates were taken away.

“So, do you guys want to carry on playing the computer, or do you want to do something else?”

“I have had enough with the computer,” Jack said.

“Why don’t you show him the loft area, and your Scalextric set?”

The area on the second floor of the house was big and, whereas it could have been used as another bedroom, it didn’t need to be used in such a way, as two bedrooms were plenty enough for the family of three. The loft area, which was converted some years previously, when Jack was a toddler, was used as an area for games—a place where one could relax. Up there in the attic, along with the Scalectrix track which was set-up, there also was a pool table, a place where they could enjoy a board game, as well as a television. There was also a personal computer there, and Jack’s father often went there to finish and complete work, especially things which urgently needed to be handed in for the following day.

Upon Jack leading his friend upstairs, upon him showing all the material things he enjoyed, the toys and the games, Andy grew excited. Jack’s house was not a place like his own, that was filled with numerous family members, a place where people seemed always around wherever one went, this house was a different animal, and was as liberally filled with Jack’s things as his was with sisters.

They enjoyed playing on the track, they enjoyed watching their cars go around, wondering in time, which one would win.

The late evening was coming up and, though the season was spring, the world was warming from the winter. And, although the days were stretched out—where light was seen for greater lengths than darkness—they weren’t yet in the heart of the summer—where welcoming light was seen well into the night, past the time when many had decided to rest in bed. Whatever in the way of light there was outside was hovering on the point of non-existence, where the void of night would open up in the cloudless sky before them. This was the hour in which Jack’s father returned home from the slog and travel of a long day.

Upon greeting his wife, who got his meal out of the oven for him where it had been resting in the remnants of the heat that cooked it, she spoke—enlightening him of all the news of the day’s novelties: her son, his friend (and so very charming he seemed), someone who clearly was more developed than her son, more lively, more sociable.

“So, they seemed to get on well?”

“Oh yes! Jack seems to be loving it.”

After he finished his dinner, which was almost twice the portion of the children’s, he made his way up two flights of stairs, into the loft area. He didn’t exactly expect to find anyone there but, upon opening the door, he found his son and friend sitting down around the Scalextric track, watching their cars go around the vast and complex course he helped to develop.

“Alright, son,” he said to Jack, “Alright there,” addressing his son’s new friend, a face that to him was a novelty.

He walked off, carefully treading over the track, trying his hardest not to disturb them in their game they seemed intently playing. He walked over to the computer and the things he needed from there—information from papers strewn over the desk, reports, balances, and such bits.

Andy seemed suddenly to grow disinterested and the thing that had fascinated him before, his car maneuvering at speed around the track, appeared as if in a sudden moment it bored him.

He walked over to Jack’s dad, who was engrossed in things to do with business, the glare of the now turned on computer screen could be seen on his face.

“What are you doing?” he said.

“Hey there. I’m just getting some work done.”

“Like, what?”

“Oh nothing, just to do with business, nothing you would understand.”

“What? You think you’re better than me?” Andy said to him in a somewhat accusatory manner, and Jack’s father could see that the tone that was once inquisitive and curious had taken on a threatening tone. He said nothing to this, just smiled at Andy, befuddled, and somewhat amused.

“You think you’re a big man or something?” Andy asked. “Do you? What a dickhead.”

“Really?”

“Look mate, are you a dickhead? I can beat you up, if you’re gonna keep acting like this.”

Andy walked over to Jack who just stood there, more confused at this sudden transformation in character. “Your Dad’s a dick,” Andy told Jack. “Don’t listen to a word he says. Listen to me.”

His father, who had now stood up, said, “Don’t pay any attention to what he said, son,” where Jack nodded over to him, acknowledging.

Though the tensions that were found between them went away when his father went downstairs and told his wife what happened, she said it was time they needed to send him home anyway. Though she found it somewhat strange that a boy that was to her once so charming, could take a swift and sudden turn in the other direction when her husband appeared and entered the house.

She drove through the streets, now blackened and lamplit—the traces of dusk that were once so present had faded into the darkness and light that previously illuminated the land had disappeared, as if the day and its lamplight were a rumour. The car ride was tense and awkward as if she were driving this child not back to his parents after a playdate, but rather into a field where he was condemned to be executed.

When they had arrived back to Andy’s house, Mary told his parents all that had happened: the whole debacle with her husband, the tension he had oddly and irrationally created out of mere air. His parents looked most disappointed with him, grabbing him by the scruff of his collar and throwing him into the house, as if this roughing him up was a prelude to a beating.

Mary and Jack drove back home and, when they arrived, it was the time most befitting that he should go to bed. His father told him that he is not allowed to talk to Andy anymore, saying that he should banish him from his life. Mary drew a bath for him and, after Jack washed, she said he could read for a few minutes before bed. She saw him off to bed and he had in his hand one of the comic books he loved. She went into his room to check on him again some fifteen minutes later, and the bedside lamp was out. Blackness covered the room like a tomb and he was only to be seen through the hallway light sleeping. Hopefully when he was sleeping, he was dreaming—where rest and lucidity was to be so alike as to be indistinguishable.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Justin Wong is originally from Wembley, though at the moment is based in the West Midlands. He has been passionate about the English language and Literature since a young age. Previously, he lived in China working as an English teacher. His novel Millie’s Dream is available here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast