by Norman Berdichevsky (December 2016)

The English Colony, Orlando

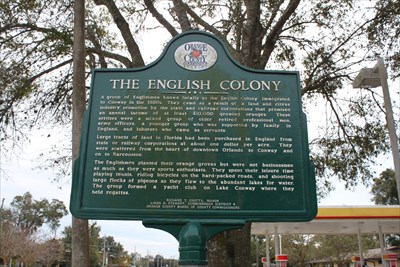

Less than half a mile from my home in Orlando, Florida at a Shell gas station is a historical marker in the Conway neighborhood that tells an interesting story. This story is in sharp contrast to the image of the Statue of Liberty’s famous inscribed poem “The New Colossus” at its base by Emma Lazarus and the current debate of how best to integrate new immigrants. Several generations of immigrants and college students could recite it by heart…..

Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me beside the golden door!

There were of course, other types of immigrants who decidedly did not fall into the “wretched refuse” category.

The marker at the gas station recounts the experiences of such a group of upper class Englishmen dreaming of wealth and extensive estates. They were spurred on by Florida state and railroad corporations in the 1880s that promised an annual income of at least $10,000 growing oranges. These settlers were a mixed group of older retired professionals, army officers, a younger group supported by family in England, and laborers who accompanied them as servants. Primogeniture was still widely practiced and those who were not first born sons often set out to make their fortunes.

This was not however the first time that British interests aspired to have a share in Florida’s fabled wealth. During the Seven Years’ War, 1756-1763, in which the British fought against both the French and Spanish, they attacked and occupied Havana, the capital of Cuba and jewel in the Spanish colonial throne. In order to ensure Havana’s return, Spain agreed to swap its territory of La Florida, including St. Augustine, the first city in what is today the United States (founded more than 40 years before the English landed in the Mayflower in Massachusetts), to Great Britain under the 1763 Treaty of Paris.

As a result of British control, good public roads were laid out, indigo, sugar cane, and fruits were cultivated, lumber was shipped, and Florida prospered as it had never before under Spanish rule. When the astonishing news of the 1776 Declaration of Independence reached St. Augustine, the people rushed in wild excitement to the public square and burned Hancock and Adams in effigy to express their opposition to rebellion. The English settlers there preferred the protection of the British crown and fleet to American independence.

East and West Florida

British controlled West Florida (known today as “The Panhandle”) was invited to send delegates to the First Continental Congress to present colonial grievances against King George III, but along with several other colonies including East Florida (under British rule but still predominantly settled by Spaniards), declined the invitation.

During the next few years several thousand loyalists fled from Georgia and South Carolina into Florida, and there was bitter feeling among the colonies. An American invasion of Florida was planned, but not carried out. Although a British expedition was fitted out at St. Augustine to invade Georgia, this also failed. Later in the war, other expeditions were planned on both sides, but did not get off the drawing board. By the 1783 Treaty agreeing to American independence, Britain received the Bahamas islands from Spain, and returned both Floridas to Spanish rule.

Following American independence, reports of Florida’s natural wealth and advantages were published in London attracting loyalists who had lost land in America. They came from South Carolina, Georgia and Bermuda. New arrivals ventured forth from England itself, convinced that Florida under renewed Spanish rule would not interfere with their Protestant faith and English language.

Under the Onís-Adams Treaty of 1819, the United States acquired Florida in return for American recognition of Spain’s rights in Texas. The European colonial power was faced by massive revolts in its New World colonies and preferred to be on good terms with the United States rather than face an eventual confrontation over Florida.

The 1880s and New British Ventures in Florida

The brief British colonial contact with Florida had left behind the notion of a land of immense riches where newcomers could still easily obtain overnight fortunes. Large tracts of land in Florida were purchased after the American Civil War by both government and private interests in England from state or railway corporations at about one dollar per acre. They were scattered around what is today Orlando.

The type of settlers encouraged to buy land and settle in the 1880s were “gentlemen” rather than pioneers or businessmen. A majority were devoted sports enthusiasts who spent much of their leisure time playing tennis, riding bicycles and shooting large flocks of pigeons that were attracted to the abundant lakes for water. These settlers formed a yacht club on Lake Conway where they held regattas.

The Polo Club

The local Polo Club was the idea of retired army officer with the unfortunate name of J.S. Swindler who arrived in 1886 and bought a large grove just west of Orlando. Games were begun in 1888 with the Orlando team playing at a local field and by 1890, the Englishmen organized the 100 member Orlando Polo Club. Teams were attracted from other states to play on the field in Conway. All of Orlando’s few thousand residents attended to cheer for their team while the ladies dutifully served tea on the grounds. It is hard to imagine an environment more remote from the immigrant epic immortalized in Emma Lazarus’ poem.

Another agriculturally based settlement was another short-lived English colony at Narcoosee, a few miles south of Orlando. This settlement had its origin in the Florida Agricultural Company, a land promotion concern that speculated in lands bordering Orlando during the 1880’s. The company purchased a twelve mile square tract of land and announced plans to promote upper class English immigrants to settle in Florida to carry on their lifestyle. The original concept of the company was to furnish English people of means with an opportunity to make homes for themselves and speculate in real estate. Only a few investors were attracted to the plan. By 1884, the settlement had only a few scattered homes, one saw mill, and a few young orange orchards.

A speculator, J.B. Watson bought five hundred acres of virgin land and wrote an enthusiastic pamphlet describing the many wonders of Florida to draw new settlers to Narcoosee. By 1885, other investors had become intrigued with the English settlement efforts and additional promotional pamphlets circulated throughout England.

The majority, as in Conway, were from wealthy families who had the means to construct tennis courts, polo fields, cricket fields, and golf courses – a scene that provoked sarcastic or envious criticism from other white Floridians (themselves of English origin) who by this time included not only typical Southerners, but wealthy newcomers from the Northern states who had served in the Civil War and were intrigued with the semi-tropical paradise they envisioned in Florida.

The towns with names such as Winter Park (suburb of Orlando), Winter Garden, and Winter Springs recall the source of these first settlers who came at first, just to spend the winter, but eventually stayed to become permanent year-round residents. The architecture of homes in these towns still recall their former New York or New England origins

The unexpected and disastrous freeze of 1894-95 utterly destroyed the English colonies’ citrus groves, and their will to survive. While their American neighbors muttered “I told you so” about the English colonists’ staying power and ability to meet adversity, the English newcomers abandoned their creation with a haste that even shocked the local citizenry. As one commentator remarked, “They departed for England abandoning groves, homes, furniture, with tables set and dishes unwashed…” The dreams of an affluent English town and life style in Central Florida vanished. Partially to blame were the private land companies who had sold the newcomers a bill of goods and lured them with promises of a luxurious life style without the administrative talent or professional knowledge of agriculture and the realities of Florida’s environment.

The Americans from the Northern states had more resources to draw upon and links with a large railroad or land company possessing considerable capital reserves to meet unexpected contingencies. These companies supplied the financial stability necessary for the conditions then existing in Florida, but unable to provide the effective, on-site leadership in the “English” colonies. Almost all the 200 Englishmen running the orange groves in the Conway area returned to England or made new homes in even more distant Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa.

In his outstanding, insightful book “Mexifornia” (2nd. Edition, Encounter Books, 2007) dealing with the failed policies of integration of illegal Mexican migrants and even legal immigrants so near to their former homes, author Victor Davis Hanson had this to say ….. “Had Mexicans flocked to Costa Rica or had New Zealanders rushed into Los Angeles, the present problems of both hosts and guests would be non-existent.” (p. 21). Such a test case already exists in the case of Florida’s English colonies of the 1880s. The new residents of the Central Florida settlements shared the same ethnicity, language and religion as the veteran Anglo-American population but not their pioneer values.

By the 1890s, without fear of any threat from abroad (except for a brief moment in 1898 when alarmists raised the spectacle of an imminent Spanish invasion to retake Florida), the local population in Central Florida saw the English upper class newcomers only as ungrateful and unable to support themselves and their exaggerated life style so out of touch with the difficult environmental conditions they and their ancestors had struggled to overcome.

Hanson was correct; values and the will to integrate is the formula for success for immigrants and not a shared ethnicity, language, and religion. In fact, the brief Spanish-American War of 1898 provided the test of combat fire for many “new Americans,” immigrants from Southern, Eastern and Central Europe. Many of them were thrown together with veteran Anglo-Americans in the armed forces and included many thousands of volunteers among native-born citizens of Spanish origin in both the Southwestern United States and Florida whose ancestors had been the first white European settlers in what is today the United States. These “Hispanic” American citizens were the forerunners of patriotic Americans who followed them in both World Wars – the millions of German-Americans, Italian-Americans and Japanese-Americans who did not question their loyalty to the United States.

The overwhelming victory in 1898 produced an era of “good feeling” and stimulated a wave of patriotism in which divisions of ethnicity, birth, language, religion and even race (for a moment) were submerged. It ameliorated the old wounds of the American Civil War between North and South as well and embraced not only the exile Cuban community residing in Florida (Ocala, Tampa and Key West) and working in the manufacture of cigars, but the older established community of true ”Hispanics” who traced their ancestry back to the first Spanish colonial settlers in East Florida-St. Augustine. None of these U.S. citizens of Spanish cultural heritage felt an affinity for the monarchist Spanish regime and were anxious to prove their patriotism. The same was true of Mexican-Americans in the Southwest.

The will to integrate is the only successful formula for immigrants. No amount of the current subsidies, workshops in self-esteem, vocational training, free medical care, bilingual education, classes in remedial English, low in-state tuition for illegal aliens, acceptance of Spanish as coequal by every government agency, provision of welfare benefits and drivers’ licenses prior to acquisition of citizenship, or programs encouraging “Chicano pride” will avoid the threat of “Mexifornia” with its large contingent of young disaffected illegal aliens who resent their status and romanticize failed states such as Mexico from which they have fled.

____________________________

Norman Berdichevsky is the author of The Left is Seldom Right and Modern Hebrew: The Past and Future of a Revitalized Language.

To comment on this article or to share on social media, please click here.

To help New English Review continue to publish interesting and informative articles such as this one, please click here.

If you enjoyed this article and want to read more by Norman Berdichevsky, click here.

Norman Berdichevsky contributes regularly to The Iconoclast, our Community Blog. Click here to see all his contributions on which comments are welcome.