Francis Brett Young: An Appreciation and a Reminiscence

by Jillian Becker (February 2021)

.jpg) Black Country, Night, With Foundry, Edwin Butler Bayliss

Black Country, Night, With Foundry, Edwin Butler Bayliss

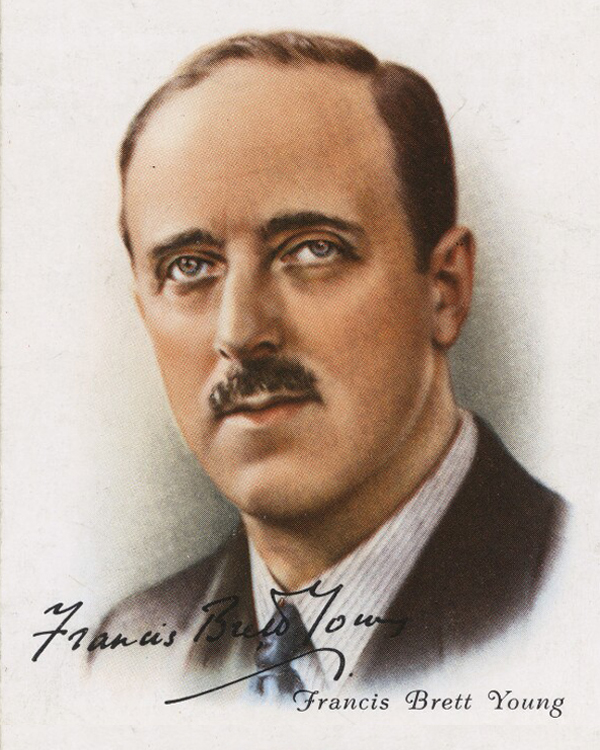

Francis Brett Young was an English writer, deservedly famous in his day. His books sold in huge numbers. From some of them popular films were made. He is little written or spoken of now, though many of the books are still in print, and uniform sets of them are to be found in most well-stocked second-hand bookshops.

We had some of them in the library of my childhood home in Johannesburg; among them Portrait of Clare, Doctor Bradley Remembers, and My Brother Jonathan. The last was not only made into a film (in 1948), but also adapted for a television series (in 1985), in which Daniel Day Lewis played the eponymous role of Dr. Jonathan Dakers.

I re-read those three books recently (and some others by Brett Young that I had read long ago or never before). The time of their stories is the late 19th and early 20th centuries; the place, the Black Country of England, the most heavily industrialized part of the West Midlands, where blackness peppered everything, the mansions of the rich and the slums of the poor.[*] And there Brett Young himself was born, the son of a doctor, in the town of Halesowen, near Birmingham, in 1884.

I re-read those three books recently (and some others by Brett Young that I had read long ago or never before). The time of their stories is the late 19th and early 20th centuries; the place, the Black Country of England, the most heavily industrialized part of the West Midlands, where blackness peppered everything, the mansions of the rich and the slums of the poor.[*] And there Brett Young himself was born, the son of a doctor, in the town of Halesowen, near Birmingham, in 1884.

Dr. Bradley and Dr. Dakers are general practitioners, as was Francis Brett Young himself. As soon as he was qualified, he signed on as a ship’s surgeon and voyaged to the Far East. On his return to England he purchased a practice in Devonshire and worked there from 1907 until he joined the Royal Army Medical Corps in the First World War. He was “invalided out,” gave up medicine and became a writer.

His stories are vivid and moving; his characters, even the cameo portraits, distinct and memorable. As records of a real world, a real era when Britain ruled a vast empire (of which Britain itself is now officially ashamed) they may be trusted. A comparison between Francis Brett Young and Somerset Maugham is inescapable. Both were doctors who became writers. They were compatriots and contemporaries of similar education. Both wrote prolifically; both traveled widely; both had a strong sense of irony manifest in many of their short stories. Both portray a society, high and low, mostly of an England past and gone; few of its virtues are still virtues, few of its vices still vices. I wonder  why Maugham is better remembered and apparently held in higher esteem than Brett Young. I have not read all the works of either of them, so I may be mistaken but, judging by what I have read, I think they are equal in achievement. While their works are similar in many ways, there are distinct differences. There is more humor in Maugham, more passion in Brett Young (yet I prefer Brett Young). Maugham did not care for nature and only mentions it when necessary; Brett Young loved nature, and writes about it beautifully, in both its vastness and its minuteness.

why Maugham is better remembered and apparently held in higher esteem than Brett Young. I have not read all the works of either of them, so I may be mistaken but, judging by what I have read, I think they are equal in achievement. While their works are similar in many ways, there are distinct differences. There is more humor in Maugham, more passion in Brett Young (yet I prefer Brett Young). Maugham did not care for nature and only mentions it when necessary; Brett Young loved nature, and writes about it beautifully, in both its vastness and its minuteness.

From Far Forest:

The upper sky was limpid and full of light. Where it ended, the hills and low-lying cloud that ringed the horizon were so drenched and lapped in the fire of sunset that vapour and stone alike appeared to be swimming in a molton fluid. It was the contrast between that fiery rim and the darkness of the river valley lying in shade, that made the expanse of Werewood, which filled it, appear so sombre. There it sprawled, the great forest, embracing Severn, obliterating the contours of the tumbled hills, lying like a dark stain spilt on the darkening green.

And:

In the depths of Werewood wild cherry-trees rose like puffs of white smoke or hung tangled like fallen cloud. In April, primroses tufted the brims of the Lem Brook, the Wild Brook, the Gladden; they powdered the hedgerows with sulphur and thrust their pink stalks through the drift of dead leaves to mingle their fainter perfume with that of white violets.

From City of Gold, a passage where two men are exploring the gold reef of the highveld, in a very long story about the founding of Johannesburg (in the real history of which my own ancestors played a part):

Every other bush was draped with the gauzy sloughs of snakes; and once, as his hand groped upwards, he saw the flash of a cobra’s brown mail as it whipped through the bushes and vanished beside his feet.

Far Forest was the only Brett Young book I had read before I met the writer. I found it in my school library. I loved it. It was one of the novels that made me want to be a novelist. It opens with a description of a chain-making town in the Black Country:

Jenny Hadley was born and reared at Mawne Heath … a blasted heath if ever there was one. … Blighted by the soot which falls perpetually from the smoke-stacks of the Great Mawn Furnaces or is sifted and blown, in fine particles, from the spoil-bank of Timbertree Pit, or buried under cinder and slag. … The heath itself is treeless, though it lies low; wind scrapes it like a razor. Its air is thin and acrid to the tongue …

I was fifteen when I met him, during our family’s annual seaside holiday on the Cape Peninsula. The setting of the story could not be more different from Jenny Hadley’s.

On the warm Indian Ocean side of the Peninsula there is a long row of villages threaded together by a road and a narrow-gauge railway along which a wailing electric train traveled (and probably still does). One of them is St. James. The terraces and front rooms of the St. James Hotel, where we stayed, commanded a splendid view of wide False Bay, from the blue hills of Hottentot’s Holland on the left, marking where Cape Aghulas lies—the infamous “cape of storms” (where Bret Young in City of Gold, and many others maintain that the two oceans, the warm Indian and the cold Atlantic meet) —almost to the port of Simonstown on the right; though not as far as Cape Point where acres of flat rocks are iced like cakes with the guano of cormorants (and where I and many others maintain that the two oceans meet, under a perpetual roll of mist). All round the shore the sound of the sea speaks happiness and the balmy air fills you with it. Far out the strong blue of the water joins the delicate blue of the sky with a line so fine the two become a diphthong.

The beach at St. James is part white sand, part brown rock. In the shallow rock-pools tiny brightly-colored fish dart about. The waves crash further out and the foamy water is sent flowing and then trickling round the rocks to refresh the calm backwater. There is a walled-in swimming pool which was calm and safe for children—and for George Bernard Shaw whom I watched swimming in it one summer in the late 1930s—except at high tide when the big waves come leaping over the walls, sending up fountains of spray and launching waves through the pool.

Behind the hotel a mountain rises, the spine of the Peninsula. About a third of the way up runs a corniche, a pleasure road a few miles long, cut into the side of the mountain for holiday-makers to drive along simply to enjoy the view. Between the lower and the higher road are tiers of houses, all looking out to sea. Steep flights of steps lead up and down to them.

To one of them we climbed, my mother and I, on a typically halcyon afternoon in December 1947 to visit the Brett Youngs, Francis and Jessica. My parents had been introduced to them by somebody and were invited to tea. I went instead of my father. I was quietly and rather tensely excited.

At first I was in awe of the famous man, and too shy to say much, but soon he made me feel how nice he was. While he talked he looked at me as often as he did at my mother. Mrs. Brett Young paid me no attention until she’d finished pouring the tea and passing the cups. Then she fixed her eyes on me for a full minute or so—I was aware of her gaze though I did not meet it—and came to a conclusion. “Oh well,” she announced, “we can’t all be pretty. There are other qualities one might have that would make up for it.”

I suppose the fact that I have never forgotten her remark is proof that it hurt my unconfident vanity.

When the cups were cool and it was nearly time to leave, I became bold enough to ask Dr. Brett Young how old he was when he wrote his first published novel. I wanted to know because I wondered if I was set to be a late developer as the novelist I intended to be. Before he began to reply, his wife called sternly, “Oh, Francis wrote none of his important books before we were married.” So I never got my answer from him, but her interruption gave me the reassurance I sought.

He saw us to the door, and there he presented me—not my mother—with a signed copy of his epic poem The Island, a verse history of Britain. (Perhaps because I told him that I loved Far Forest, but I don’t remember if I did.) I found it rather heavy going, but was proud to own it.

In 1963, traveling by train from London to Yorkshire to attend a funeral, I passed through the Black Country. I saw the words Far Forest on a signpost. It’s a village as well as a region. I saw miles of factories with their huge double doors open wide and their insides as red as if they themselves were furnaces. And I remembered Frances Brett Young’s description of women chain-makers who worked in such hells, stripped to the waist, bosom and arms glowing with sweat.

Here’s the passage from Far Forest:

In the Mawne Heath chain shops … a compost of sweat and grime reduced clothes and faces to a uniform blackness beneath which shapes and features could scarcely be discerned. But for their skirts and aprons of spark-singed sacking, no casual observer would have taken these bedraggled figures, who swung their three pound hammers and twisted the red-hot rods … for women, unless indeed, he chanced to see them in summer, when the heat of the sun without and that of the hearths within, compelled them to strip their clothes to the waste and display their assortment of withered and pendulous or young and buxom breasts. They wore men’s caps on their heads and men’s boots on their feet; their arms and shoulders were muscled for manly labour, their movements uncouth; their voices issuing from mouths parched by dust and hot fumes, were raucous …

I was a little disappointed that they were no longer to be seen.

Francis Brett Young died in 1954. His widow wrote a biography of him and presented a copy to my parents. I learned this because one of my daughters found it among the books she inherited in 1984. The inscription on the flyleaf is dated 1963, and the place of the presentation noted as the Mount Nelson Hotel in Cape Town. I also learned from her book, to my surprise, that Far Forest was finished at the Majestic Hotel in Kalk Bay, the village next to St. James, some twenty-three years before I met the author. It was in the tranquility of paradise that he had brilliantly recreated hell.

[*] Theodore Dalrymple told me: “There is a story about Queen Victoria and the Black Country. She went by train through it and the blinds of the carriage windows were drawn because the area was so dreadful. Whether this was by her own orders or those of an Aide-de-Camp, I do not know.”

__________________________________

Jillian Becker writes both fiction and non-fiction. Her first novel, The Keep, is now a Penguin Modern Classic. Her best known work of non-fiction is Hitler’s Children: The Story of the Baader-Meinhof Terrorist Gang, an international best-seller and Newsweek (Europe) Book of the Year 1977. She was Director of the London-based Institute for the Study of Terrorism 1985-1990, and on the subject of terrorism contributed to TV and radio current affairs programs in Britain, the US, Canada, and Germany. Among her published studies of terrorism is The PLO: the Rise and Fall of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Her articles on various subjects have been published in newspapers and periodicals on both sides of the Atlantic, among them Commentary, The New Criterion, The Wall Street Journal (Europe), Encounter, The Times (UK), The Telegraph Magazine, and Standpoint. She was born in South Africa but made her home in London. All her early books were banned or embargoed in the land of her birth while it was under an all-white government. In 2007 she moved to California to be near two of her three daughters and four of her six grandchildren.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast