Frederick Forsyth’s ‘The Shepherd,’ a Christmas Story

by Pedro Blas González (December 2023)

For tonight there would be no wandering aviators to look down and check their bearings; tonight was Christmas Eve, in the year of grace 1957, and I was a young pilot trying to get home to Blighty for his Christmas leave. — Frederick Forsyth, The Shepherd

Frederick Forsyth’s The Shepherd is a novella of man’s instinct for survival and longing for the warmth and safety of home. The tale of a pilot lost in terrible flying weather may appear simple. Instead, the book is actually a multi-layered, life-affirming story of good will and a Christmas miracle.

Frederick Forsyth’s The Shepherd is a novella of man’s instinct for survival and longing for the warmth and safety of home. The tale of a pilot lost in terrible flying weather may appear simple. Instead, the book is actually a multi-layered, life-affirming story of good will and a Christmas miracle.

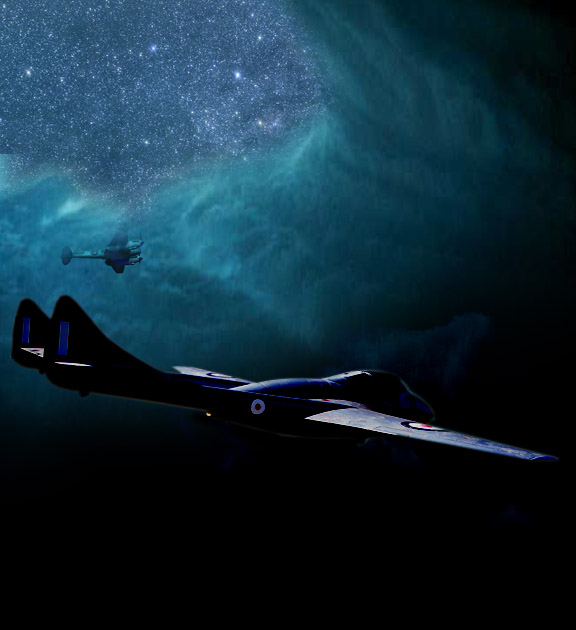

A Royal Air Force pilot flies a de Havilland Vampire DH100 jet and becomes lost in disorienting fog, after losing the compass and other instruments due to an electrical failure. The Shepherd is also an intriguing magical story of the soul of a dead pilot saving the life of a pilot in distress, thus, acting as a shepherd of life.

Forsyth explains how, in the winter of 1974, his wife asked him to write her a ghost story. According to the author of The Day of the Jackal, The Odessa File, The Dogs of War, The Fourth Protocol and many other novels, he didn’t know how to write a ghost story. He had never written one before. This now classic illustrated novella, which was published in 1975, contains fifty-two marvelous black and white drawings that gracefully highlight Forsyth’s story of hope.

A young RAF pilot is stationed in a military base in Germany. The protagonist is excited to fly back home to RAF Lakenheath in Suffolk, England, on Christmas Eve. The year is 1957. The pilot anxiously anticipates being reunited with his family in several hours. First, he must fly his Vampire through a frigid, dark night.

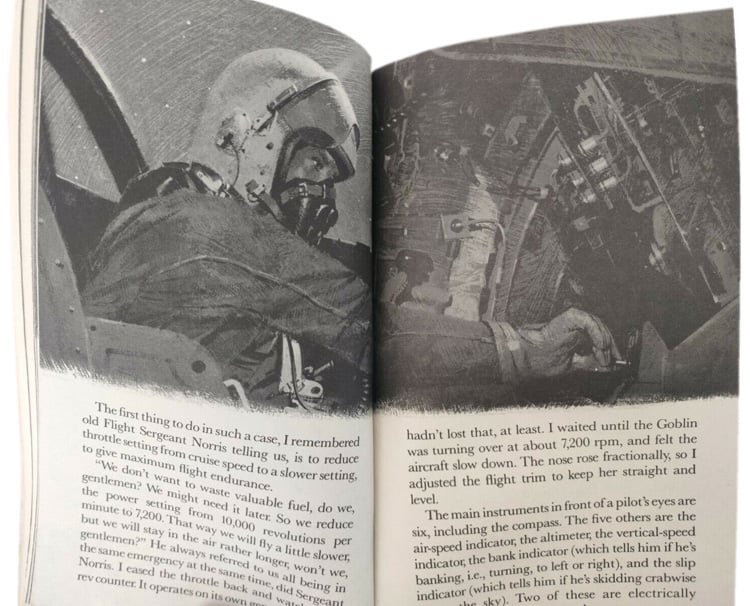

The post-World War II date of the story is significant given that the story is not about battle. The protagonist is not engaged in a mission or military exercise. This enables Forsyth to develop a story that is centered around the joy of flying, solitude, and the pleasure pilots take in being momentarily freed from terrestrial constraints, in addition to the maze of thoughts that pass through a pilot’s head in times of distress. The author devotes one layer of the story to highlight the beauty of flight and the stoic psyche of pilots. Forsyth, himself a pilot for the RAF, which offers the story verisimilitude, flew the de Havilland DH 100 Vampire, a formidable airplane capable of reaching a cruising speed of 535 miles per hour.

The Shepherd brings to mind many of the themes one finds in Antoine de Saint Exupéry’s (the “Winged poet”) classic 1939 novel Wind, Sand and Stars (Terre des hommes), a work that showcases the exploits of the author of The Little Prince during the time Saint Exupéry was an airmail pilot for Aéropostale—alongside other airmail pioneers, the French pilot, Jean Mermoz, being one of these.

At the start of the novel Forsyth has his protagonist narrate the joy of flying, as the pilot enjoys time alone in the protective warmth of the Vampire’s cockpit, and the joy of returning home for Christmas. The narrator is poetic in juxtaposing his solitude, which is conducive for reflection, and the almost make-believe world ‘down there,’ as he experiences the world from an altitude of 5,000 feet: “Down there amid the gaily lit streets the carol singers would be out, knocking on the holly-studded doors to sing Silent Night and collect pfennings for charity. The Westphalian housewives would be preparing hams and geese.”

At the start of the novel Forsyth has his protagonist narrate the joy of flying, as the pilot enjoys time alone in the protective warmth of the Vampire’s cockpit, and the joy of returning home for Christmas. The narrator is poetic in juxtaposing his solitude, which is conducive for reflection, and the almost make-believe world ‘down there,’ as he experiences the world from an altitude of 5,000 feet: “Down there amid the gaily lit streets the carol singers would be out, knocking on the holly-studded doors to sing Silent Night and collect pfennings for charity. The Westphalian housewives would be preparing hams and geese.”

After climbing to 15,000 feet, the pilot cherishes the joy of Christmas—Weihnacht: “It’s the same all over the Christian world.” The fifty-six degrees below zero hostility of the lonely night, with the stars “sparkling away there in the timeless, lost infinities of endless space” makes him appreciate his solitary trek home.

The glass canopy of the Vampire affords the pilot a clear view of the crisp stars shimmering in the wintry night. Below, is the “heavy brutality of the North Sea, waiting to swallow up me and my plane and bury us for endless eternity in a liquid black crypt.” Once airborne, pilots experience a form of mystical timelessness that is difficult to convey to non-fliers.

The mood of The Shepherd is comparable to the narrative structure and thematic of Hemingway’s The old Man and The Sea, where solitude, spirit-crushing danger and perseverance take center stage. The real drama of The Shepherd is dictated by the unknown, fate, and ultimately, the intertwined trajectory of the life of the protagonist and a deceased RAF pilot, Johnny Kavanagh, ‘the shepherd’ who died fourteen years earlier, on Christmas Eve. Like Santiago in The Old Man and the Sea, Forsyth’s RAF pilot protagonist is pinned against natural forces that test the limit of human fortitude, know-how, courage … and Christian faith.

After the airplane’s electrical system undergoes a catastrophic failure—the compass and radio stop working—the pilot’s much valued solitude becomes a crushing omen of bad things to come. When the fog begins to roll in from the North Sea, the narrative turns into a desperate and bitter soliloquy: “You stupid bastards, why don’t you look at your radar screens? Oh, God, why won’t somebody see me up here?” After the pilot’s anger subsides and helplessness creeps in, five minutes later, he says, “I knew, without any doubt of it, that I was going to die that night.”

The beauty of The Shepherd as a literary tale is the ease with which Forsyth weaves the specs of the aircraft and art of flying the complex, powerful de Havilland Vampire, of which only 3,268 were built between 1946 and 1955, with the supernatural aspect of the story: life and death, and meaning and purpose that make coherent the intersection of life and death. The Shepherd is a mixture of horse-sense, bone-jarring realism, and Christian hope that surprises readers who expect a straightforward aviation adventure story.

The beauty of The Shepherd as a literary tale is the ease with which Forsyth weaves the specs of the aircraft and art of flying the complex, powerful de Havilland Vampire, of which only 3,268 were built between 1946 and 1955, with the supernatural aspect of the story: life and death, and meaning and purpose that make coherent the intersection of life and death. The Shepherd is a mixture of horse-sense, bone-jarring realism, and Christian hope that surprises readers who expect a straightforward aviation adventure story.

The fog becomes thick and oppressive, otherwordly. With no radio to communicate with ground control, the protagonist is overjoyed to see, or so he believes, that a nearby airport has sent up a shepherd airplane—an older generation World War II, propeller powered de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito fighter-bomber (“Mossie”) —to help him land in the deadly fog. The other airplane flies alongside the protagonist, barely visible. The pilot of the de Havilland Mosquito is wearing a leather helmet, goggles and oxygen mask: “I caught sight of the nose of the Mosquito. It had the letters JK painted on it, large and black.”

Eventually, the protagonist is guided down by the shepherd to land in a non-operational RAF station that has no navigational equipment, not even a beacon. Half-way down the runway, rolling “through a sea of gray fog,” the airplane runs out of fuel and the pilot is picked up, a few minutes later, by one of the two station attendants on duty. The man, who is Flight Lieutenant Marks, is shocked that anyone could have landed a disabled airplane in such atrocious weather conditions.

Once inside the station’s mess hall, the pilot makes several telephone calls to other bases to inquire about the identity of the shepherd pilot who guided him down. A window blows open and the pilot looks out into the dense, cold fog before shutting it close. He then stares at a portrait of a young pilot who stands next to a de Havilland Mosquito. The photograph is of a RAF pilot named John Kavanagh. The protagonist remembers seeing the initials JK on the side of the Mosquito. “Johnny went out on patrol on Christmas Eve 1943 and never returned,” the station operator tells the protagonist. That was fourteen years ago. Johnny was lost in the North Sea.

While the protagonist of The Shepherd does not know the identity of the pilot that helped him land in the fog, the story’s ending suggests that human wellbeing and survival depend on more than just competence and luck.

While reading The Shepherd is recommended, you can listen to the CBC adaptation, narrated by Alan Maitland, here.

Table of Contents

Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy in Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay, Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man, Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity. He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998). His most recent book is Philosophical Perspective on Cinema.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast