From a Veteran of the Years of Lead: Adrenaline Junkies

By Guido Mina di Sospiro (July 2020)

The following piece refers to the late 1970s in Italy. It may serve as a cautionary tale about how . . . colorfully protest can evolve.

That year the Red Brigades showed Italy and the world the meaning of the word “industriousness.” In a country paralyzed by strike after strike, they were working overtime, ever diversifying their approach to the fine art of terrorism. Eventually credited with about fourteen thousand acts of violence within the first decade of their existence, the Red Brigades’ work ethic was impeccable. In their communiqués, usually issued after an attack, they resorted to expressions such as “destruction of enemy troops,” “target annihilation,” “firepower,” as if they were field marshals while they routinely shot defenseless people at pointblank, which was, they realized, the most efficient way to go about it for maximum results from minimum efforts.

Their founder having escaped from prison, and then having been arrested again, they underwent a second founding through which all activities and cells were reconfigured in order to maximize their “attack to the heart of the state.” And maximize it they did. Ever an equal opportunity giver, they resolved not just to wound or to kill policemen, but just about everyone who stood in their way: judges, lawyers, executives, journalists (among them also a former partisan and a communist), professors—everybody had their opportunity to be shot at. They also kidnapped, admittedly preferring the rich, for whom a ransom would be paid. Various brigatisti managed to escape from prison, with suspect ease, some remarked.

At the end of that year, the Red Brigades linked up with their German counterpart, the Red Army Faction (a.k.a., Baader-Meinhof Group). The involvement of the Italian terrorists with their German peers culminated in the German Autumn, the most extensive criminal and political confrontation in Germany since the end of WW II.

There were other international ramifications. The KGB, the Soviet Union’s main security agency, sponsored the Red Brigades, and delegated affairs to the Czechoslovak StB, a secret police force. Soviet and Czechoslovak arms and explosives were supplied via the Middle East along the smuggling routes of heroin traffickers. And training camps were the responsibility of the PLO, the Palestine Liberation Organization, who usually set them up in Syria and North Africa.

Other exemplary hard-workers, Front Line, began to shoot in the legs, kill, and sabotage on a large scale at around that time.

There were numerous other small clandestine groups, a whole nomenclature of them, that were trying to emulate the Red Brigades.

Not that we, the stupefied people, had a clear picture of what was going on at the time, though we did wonder at the organizational skills of the Red Brigades, and how they could support so many activities. As it has transpired, the Italian Communist Party was aware that the KGB was sponsoring the Red Brigades, and had lodged, belatedly, complaints at the Soviet Embassy in Rome, which had been neglected. But to us, it all registered as a succession of violent deaths, by then all over the country, punctuated by demonstrations so brutal that a better way to describe them would be battles.

Something out of the ordinary even for the chaos in which Italy found itself had happened early on that year. At the University of Rome, which had been occupied for days, a new group, Autonomism, booed a trade unionist, a sacred cow of the institutional left. This was unprecedented and, until then, inconceivable. The official left was dumbfounded: the demiurge, as they saw him, of the communist trade union had been a victim of lèse-majesté. And more: he was physically assaulted, and his bodyguards barely managed to save him.

In Bologna, students from Autonomism attacked a hall in which other students, from Communion and Liberation, a Catholic group, were holding a meeting. Rebuffed, they redoubled their efforts. The police were called in. Clashes between ultra-left militants and the police ensued, and grew increasingly violent.

More ultra-left militants arrived, with the usual arsenal of iron bars, cobblestones, Molotov cocktails and sundry weapons. They meant business.

Eventually, one Molotov cocktail landed inside a police vehicle, beside the driver’s seat. The car went up in flames instantly. The policeman who was driving managed to jump out if it. Still under attack, he pulled out his service pistol, and shot six times.

The group Continuous Struggle had earned on the battlefield the nickname Hare Brigade for their talent in fleeing both swiftly and inventively. Such a talent deserted one of their sympathizers, that day, when a bullet hit him in the back as he was escaping, and killed him. It’s never been established if the panicked policeman was responsible for his death, as the bullet entered and exited the activist’s chest.

For the next few days, weeks, months Italy’s major cities erupted, with battles everywhere because of which there were more casualties, both among the militants and the police, as well as among random bystanders.

This modus operandi was very different from the deliberately targeted executions carried out by the Red Brigades and other such groups; it too resulted in violent deaths, but they were erratic.

The 1965 protest song Eve of Destruction by P. F. Sloan, sung most successfully by Barry McGuire, was adopted by an Italian singer-songwriter from the ultra-left, who changed its lyrics. From an anti-war statement, in the Italian version it became a rousing call to arms. The Hour of the Gun’s refrain went: “What else do you need, comrade, to understand that the hour of the gun has come?” In between the refrains was a litany of the triumphs of communism around the world. “Just violence” was invoked, too. Such a song became an anthem of the ultra-left, so it was not entirely a surprise when the gifts of the former partisans—the P38 handguns—finally materialized in their heirs’ hands.

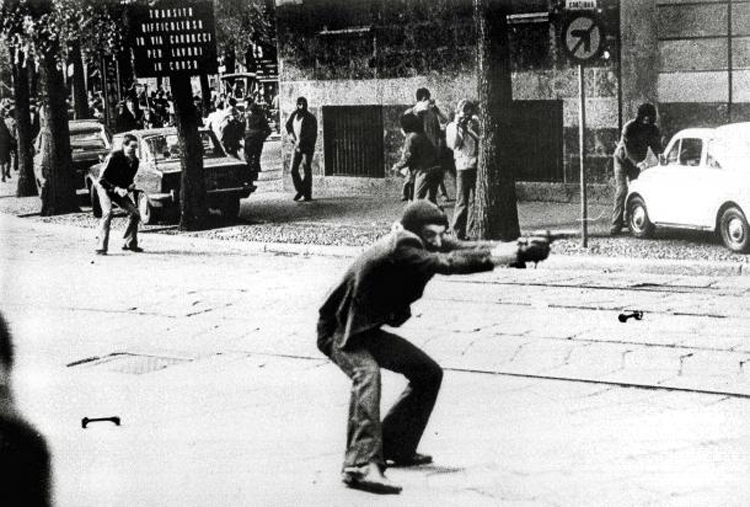

It was around this time that, in Milan, kids slightly older than I was were photographed shooting straight at the police. On the other side of the photo, a policeman was killed. The transition to firearms had seemed natural, for some belated, and shooting at the police was more expedient than throwing assorted objects at them. Again, people were dying on all sides.

It seemed unavoidable when, in fact, it could have been avoided altogether. What was the point? I asked myself at the time. One thing was to destabilize the institutions by hitting either consequential or symbolic targets, as the terrorists did (which, from a Machiavellian perspective, made sense); another one was to attack policemen during demonstrations indefinitely until someone on either side got killed.

Policemen were not the stereotypical trigger-happy fascistoids. They were the sons of peasants from the impoverished south who had found, in enrolling, a way out of indigence. They really didn’t care to defend whatever they were sent to defend. It had come to the point that they were merely trying to save themselves, as during the clashes they were usually outnumbered. Very young, undertrained, semiliterate and terrified, the authorities who employed them couldn’t realistically consider them anything other than low-cost and highly replaceable cannon fodder. With all that, they were expected to be possessed of supreme aplomb and never to retaliate with deadly force to the militants’ “provocations,” which by then amounted to assassination attempts.

When a policeman was killed, the authorities would deplore his death (hypocritically, as they ought to have utilized seasoned and better-trained professionals armed with rubber bullets and other non-lethal crowd-control devices other than teargas, which had proved ineffective), while from the left to the ultra-left the comments would range from “risks of the trade” to “good riddance.”

When an ultra-left militant was killed, on the other hand, it was nationwide pandemonium.

In an attempt to account for the lunacy of those days I have come to two conclusions, which I have never read anywhere.

The killing of an ultra-left militant by the police may be an asset to the whole revolutionary movement. The new cult needed its martyrs. Not only did they legitimate instant and nationwide retaliations fueled by increased hatred and rage, but one day they could be seen as the founding fathers of the revolution. Keep in mind that this was happening in the country of Machiavelli.

The other conclusion concerns the true nature of the incessant and yet pointless violent attacks against the police by the ultra-left militants. Heroin by then had made a triumphant entry into Italy. Some have recently alleged that a collaboration between drug traffickers and government forces was behind it, in a bid to “tranquilize” the various anti-establishment movements, and then to quell them. Whether or not in collusion with government forces and secret services, drug traffickers withdrew all other drugs, including marijuana, from the illegal marketplace and supplanted them with heroin, sold at first at extremely low prices. When a multitude of young people became addicted, prices levitated, while other substances were reintroduced. But a drug that was easily available to all, and for free, was adrenaline.

There was no bungee jumping, then, or whitewater rafting, or other such pastimes for first-world thrill-seekers. The word “adrenaline” was known chiefly to medical doctors, who rather referred to it as “epinephrine.” But the astute ultra-left militants were on to something. Fleeing precipitously from demonstrations when the police charged them was not only proof of sagacity in urban guerrilla warfare tactics, but gave them an adrenaline rush—as did, before that, assaulting the police. The adrenaline hormone is produced, precisely, by the fight-or-flight response; militants experienced both, often in quick succession, and repeatedly within the same day. By self-inducing the fight-or-flight response, the adrenal gland would release adrenaline into their bloodstream. Other catecholamines are released during such stress-inducing activities, as well as endorphins. While the main function of this endogenous opioid is to inhibit the transmission of pain signals, it may also induce a euphoric state almost identical to that induced by other opioids, such as morphine and heroin. An accelerated heart rate, dilated blood vessels, increased glucose levels as well as oxygen supply to the brain gave the militants the temporary feeling of being high. The animality of all this left them feeling exhilarated, high on life. While they might have believed that ideology was informing their actions, that was rather the privilege of the terrorists, with their calculated and surgical attacks. For the ultra-left activists, be they students or not, ideology had been the driving force at first. By the time the clashes with the police degenerated, adrenaline had taken over.

The militants’ being adrenaline junkies would explain the behavioral pattern of alternated attacks against, and escapes from the police—cui bono? To whose benefit? Then again, should one of the adrenaline junkies meet with a violent death because of such intemperances, he or she could serve the revolutionary cause as a martyr.

«Previous Article Home Page Next Article»

__________________________________

The Story of Yew, The Forbidden Book, The Metaphysics of Ping Pong, and Forbidden Fruits.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast