GI Frontline Rabbi during WWII: David Max Eichhorn

by Jerry Gordon (December 2022)

US Army Chaplain Captain Rabbi David Max Eichhorn at Nuremberg April 22, 1945

November 11, 2022 Veterans Day commemorations were held in many Jewish houses of worship in the US. American Jews have honorably served in all of its wars since the Revolution. Jewish chaplains were first nominated under President Lincoln to serve on the Union side during the Civil War initially as hospital chaplains. Beginning with World War I spiritual needs of Jewish members of the US military were met by chaplains recruited by the National Jewish Welfare Board (JWB). Many of whom performed their pastoral duties to coreligionists in the trenches of European combat During World War I. 24 Army and one Navy Rabbi chaplains served more than 250,000 American Jews during the Great War. A number of Rabbis received medals and commendations for their service under combat conditions. One pioneering Rabbi Chaplain was Captain Elkan Voorsanger who served with the 78th Division during the Battle of the Argonne receiving a Purple Heart. He was awarded a Croix De Guerre and recommended for the Distinguished Service Medal. He became known as “The Fighting Rabbi.” He also set the standard for all military chaplains to service members of the US military in the field of whatever religious denomination. During WWII more than 550,000 American Jewish men and women served in all of the armed services both at home in theaters of operations overseas. Over three hundred Rabbis were recruited by the JWB to serve the needs of Jewish armed forces members often conducting services under combat conditions. Rabbi Alexander Goode was one of three chaplains who gave up their life jackets when a troop transport was hit by a German torpedo during WWII. Their sacrifice was memorialized in a commemorative US postage stamp. For more background see The Fighting Rabbis: Jewish Military Chaplains and American History” by Albert Isaac Slomovitz”

The Ken Burns PBS documentary, The US and the Holocaust drew attention to one of those WWII Jewish Military Chaplains, Rabbi David Max Eichhorn, who was shown conducting services at Dachau after its liberation. The episode was filmed six days after the liberation of Dachau by Hollywood director of note George Stevens. Eichhorn had served as Jewish Chaplain for the US Army XV Corp from D-day through allied victory in Germany in May 1945 and the occupation that followed surrender.

His grandson, noted Washington national security lawyer, Mark Zaid, made a virtual presentation about his grandfather at a Veterans Day commemoration at Sinai Temple in Springfield, Massachusetts on Friday evening, November 11, 2022. Zaid’s practice in our Nation’s Capital focuses on clients who are spies, whistleblowers and security clearance of memoirs by sub-cabinet officials. His firm’s most notable assignments included as counsel for several witnesses in the January 6th Special US House Investigating Committee interviews.

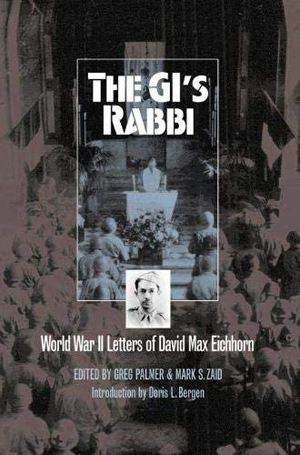

Zaid is co-editor with Greg Palmer of GI’s Rabbi: Letters of World War II by David Max Eichhorn, University of Kansas Press, 2004.

His grandfather Rabbi David Max Eichhorn (1906 to 1986) was the son of the Philadelphia haberdasher, an immigrant from Germany. After receiving his ordination from the Hebrew Union College seminary of the Reform Movement he held his first pulpit post in Springfield from 1932 to 1934. Rabbi Eichhorn who later served post World War II as field activities director for the NJWB, chronicled his exploits and reached the rank of Lt. Colonel in the US Army Reserves. He also wrote extensively on Jewish doctrine regarding intermarriage. For his meritorious services during WWII, Rabbi Eichhorn was awarded the Bronze Star.

Zaid also recounted his grandfather’s exploits in 2018 documentary, GI Jews: Jewish Americans in WWII, that included American Jewish military serving luminaries such as the late Carl Reiner, Mel Brooks and Henry Kissinger, one of the fabled Ritchie Boys of German and Austrian Jewish Refugees recruited for combat and counter intelligence assignments in the European Theater of Operations.

During Rabbi Eichhorn’s tenure at Sinai Temple in Springfield he caught the attention of fabled screenwriter, radio playwright, producer, essayist and author Norman Corwin, then a journalist with The Springfield Republican, who wrote human interest stories. Corwin facilitated publication of Eichhorn’s weekly sermons. Unfortunately, it was the depths of the depression and Temple Sinai was running into difficulties funding Eichhorn’s position. His next pulpit was a reform congregation in Texarkana, Arkansas that was founded in 1976, but alas, closed in 2014. There he and his wife Zelda raised three sons and a daughter. His last pulpit before entering US Army military chaplaincy was at Temple Israel in Tallahassee, Florida.

Eichhorn in the late thirties toyed with the possibility of serving with the Abraham Lincoln Brigade during the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930’s. About a third of the Brigade was Jewish and he thought he could serve as a chaplain in the Brigade in the fight against Fascism. He was turned down by a Brigade recruiter. But then, World War II brought the prospect of joining the fight against Nazism. Once again, he rushed to join up after Pearl Harbor in 1941 and responded to NJWB recruitment to become a military chaplain. After completing chaplaincy training and service at Croft Army base in South Carolina, he and a group of ten fellow Jewish chaplains crossed the Atlantic aboard the Queen Mary landing in England after D-Day. He was assigned to the XV Corps in France under the command of General Wade Haislip composed of the 44th and 79th Infantry Divisions, combat units of General Patton’s Third Army.

In a letter to his wife Zelda, he described what his experience was as a chaplain on the front lines driving a jeep with a Jewish six-pointed star:

My work can be described very simply; it is to hold religious services for and to give religious comfort to Jewish soldiers wherever and whenever I find them. In that it does not differ in the slightest from the work I did in the States. The only thing which is different is the surrounding circumstances. I travel around in a jeep and trailer, live in a puptent, sleep on the ground, eat sometimes quite well and sometimes not so well. I’ve become quite adept at doing a high-dive out of the jeep whenever a bullet-spitting plane with a swastika painted on it swoops down on the highway where I am riding. I’ve been shot at, bombed, and strafed so often that it has ceased to be a novelty–and it really is not as bad as the movies make it. Everybody over here is going through the same thing, and there seems to be little point in dwelling on these things continually or even often. I don’t take the vitamins anymore. It is rather unnecessary to do so when one lives out-doors 24 hours a day and seven days a week.

My work can be described very simply; it is to hold religious services for and to give religious comfort to Jewish soldiers wherever and whenever I find them. In that it does not differ in the slightest from the work I did in the States. The only thing which is different is the surrounding circumstances. I travel around in a jeep and trailer, live in a puptent, sleep on the ground, eat sometimes quite well and sometimes not so well. I’ve become quite adept at doing a high-dive out of the jeep whenever a bullet-spitting plane with a swastika painted on it swoops down on the highway where I am riding. I’ve been shot at, bombed, and strafed so often that it has ceased to be a novelty–and it really is not as bad as the movies make it. Everybody over here is going through the same thing, and there seems to be little point in dwelling on these things continually or even often. I don’t take the vitamins anymore. It is rather unnecessary to do so when one lives out-doors 24 hours a day and seven days a week.

In one of the liberated French villages, Rabbi Eichhorn reported to JWB on discovering a Righteous Gentile protecting Jewish refugees and the humanity of American Jewish and Black soldiers:

In one town alone, I found a French farmer playing godfather to 65 children and 75 adults whom he had placed in homes in six different villages. He protected them at the risk of his own and his family’s lives. At the service which I held in this city, 81 Jewish soldiers (many of whom had not been paid for as long as four months) emptied their pockets and contributed more than 5000 francs to help me in this work (finding food and clothing for the refugees.) One company of Negroes contributed its entire week’s candy ration.

One of the riveting episodes involving Rabbi Eichhorn during the XV Corps campaign retaking the Alsace-Lorraine region from German forces occurred during Yom Kippur on September 27-28, 1944. General Haislip ordered him to prepare for conducting services for Jewish troops on short notice. An abandoned synagogue was located in the frontline city of Lunéville France, still nominally in German hands. Here is what Eichhorn wrote in a report to the JWB:

Yom Kippur was on Tuesday evening and Wednesday. The preceding Friday, an order was issued by Headquarters: ‘All personnel of the Jewish faith will be excused from duty next Tuesday and Wednesday in order that they may attend Day of Atonement services in the synagogue in Lunéville.’ Quelle chutzpah! Lunéville and its synagogue were still in the hands of the Germans, two miles ahead of our most forward positions. You can imagine with what interest I read the daily battle-situation reports. Monday morning’s report stated: ‘Street-fighting continues in the city of Lunéville.’ Monday afternoon, my assistant and I headed for Lunéville. To reach it, we journeyed past our artillery, our tanks, and most of our infantry …

The city was completely deserted. Not a person was on the streets. Our hearts were in our mouths. Just as we reached the main street, we saw a big American flag being put out of a building about three blocks ahead. Never was there a more welcome sight. When we reached the building, we found inside an American military intelligence team of an officer and two men. They looked at us in amazement. ‘What in h— are you doing here, chaplain?’ ‘I’m here because I’ve been instructed to hold a Yom Kippur service in this city tomorrow evening.’ ‘Well, if you can hold a Yom Kippur service with two Jews and three Gentiles, that will be it, for there will be no more American soldiers in this town by tomorrow night. This town is still in No Man’s Land. It is not yet officially taken.’

We learned that the Germans had retreated from the city to the Forest of Parroy, about a mile west. In an atmosphere permeated with snipers, artillery shells whining around and overhead, of bombs and strafing, I began to prepare to celebrate Yom Kippur. I’ve been in some pretty tough spots the last few months, but I believe that, up to now, this one takes first prize.

There was a synagogue in the town. It was sealed up. With the aid of the French, we unsealed it. Inside, it was a mess. The Nazis had broken up and torn down everything that they could, ripped the prayer books in bits and piled the remains in heaps on the floor. We spent about two hours gathering the bits of Hebrew printing that remained. I placed the broken fragments upon the altar and there they stayed, in a place of honor, during the entire Yom Kippur service. These bits of paper, together with a shofar which was found in the debris, were the only tangible remnants of a community of 200 Jewish families.

The local people were really wonderful. They cleaned all the dirt from the synagogue. The place was strung with electric lights and decorated with French and American flags. So far as I was concerned, all this was being done because General Haislip had so ordered. I did not expect any Yom Kippur service to be held in Lunéville. I did not think that anyone would get out of his foxhole and walk toward the enemy to go to synagogue, even on Yom Kippur. Enough is enough.

But General Haislip’s hunch was right and mine wrong. At sundown on Tuesday the men came into Lunéville from all along the line, on foot, by jeep and by truck. 350 battle-grimed Jewish fighters came to the synagogue for Kol Nidre. Their places in the line were taken by Gentile comrades so that they might have an opportunity to worship. In they came, their faces coated with dirt–grim, brave, fighting sons of Judah. I tell you unashamedly that, for the first time since I have been in France, I broke down and cried. No matter what I had seen before of the wounded, the dying and the dead, I had managed to steel myself against tears, but this was too much. The noises of war raged around us as together we intoned our traditional prayers. The men kept on their full battledress and their guns were at the ready. Together we prayed that mankind might be spared another such Yom Kippur.

Many of the men were not able to remain for the entire service. They had to resume their place in the line. A bitter firefight broke out almost immediately to drive the Germans from the Forest of Parroy.

Sadly, 38 of those Jewish GIs who attended services were killed in action shortly following their return to their front-line units. Additionally, Rabbi Eichhorn lost his young assistant, the son of a leader of the World Jewish Congress.

During his Sinai Temple virtual presentation Zaid spoke about Rabbi Eichhorn holding a Jewish service with Palestinian Jewish POWs at Hitler’s Nuremberg Nazi Congress on April 22, 1945 following the conquest of the city by the 45th “Thunderbird US Army Division of the XV Corps. Eichhorn wrote:

In the jeep were one American Jewish chaplain, one American Jewish chaplain’s assistant, one Torah and ark, and five Palestinian Jewish soldiers who had been captives of the Nazis for four long years. Behind followed a second jeep bearing five American Jewish soldiers of the 45th Infantry Division, fighting soldiers who had helped destroy the citadel of Nuremberg. Slowly and proudly, the little procession drove around the stadium. It halted before the speaker’s rostrum, a rostrum surmounted by a resplendent gold-leafed swastika, the rostrum from which Der Fuehrer had, again and again, fulminated against democracy and the Jews.

The soldiers got out of the jeeps and, forming a guard of honor around the holy Ark, carried it up the steps to the speakers’ platform. Here the procession halted. The Ark was opened, and the Torah taken out. The representatives of an eternal people offered up songs and prayers of thanksgiving to the eternal God for having once more revealed to mankind the certainty of His justice and the timelessness of His love. At the end of the service, the Americans and the Palestinians joined hands and, forming a solid ring around the rabbi, the Ark and the Torah, pledged renewed fidelity to the cause of Israel and the worship of Israel’s God. Shortly thereafter … demolition charges were attached to the resplendent gold-leafed swastika atop the speakers’ platform, and it was blown sky-high. Amid the thousands of cheering beholders, none, perhaps, was more deeply moved than the little group of seven Americans and the five soldiers from Palestine who were clustered around the little jeep with the big Magen David.

Dachau was liberated on April 29, 1945 by the 42nd and 45th Infantry Divisions to the horrors of the GIs and Rabbi Eichhorn who arrived 24 hours later. Eichhorn noted what they discovered:

We saw 39 boxcars loaded with Jewish dead in the Dachau railway yard, 39 carloads of little, shriveled mummies that had literally been starved to death; we saw the gas chambers and crematoria, still filled with charred bones and ashes. And we cried not merely tears of sorrow. We cried tears of hate.

Rabbi Eichhorn was busy with conduct of funerals, separating disputes between warring prisoners, especially between Poles and Jews, as well as, caring for the immediate needs of survivors, especially food and medical treatment. Zaid in his virtual presentation at the Sinai Temple noted that Dachau unlike Auschwitz Birkenau was set up as a concentration camp located in close proximity to urban areas near Munich. It was impossible for civilians not to have known what was going on.

Lt. Col. Felix Sparks of the 45th Infantry Division, the principal commentator in Alex Kershaw’s book The Liberator: One World War II Soldier’s 500-Day Odyssey from the Beaches of Sicily to the Gates of Dachau, reported on the horrendous scene:

The first evidence of the horror to come was a string of about forty railway cars on a siding near the camp entrance, Each car was loaded with emaciated human corpses, both men and women. […]

The scene near the entrance to the confinement area numbed my senses. Dante’s Inferno seemed pale compared to the real hell of Dachau. A row of small cement structures near the prison entrance contained a coal-fired crematorium, a gas chamber, and rooms piled high with naked and emaciated human corpses. As I turned to look over the prison yard with unbelieving eyes, I saw a large number of dead inmates lying where they had fallen in the last few hours or days before our arrival. Since all the many bodies were in various stages of decomposition, the stench of death was overpowering.

Zaid spoke in his virtual Sinai Temple presentation of his grandfather’s horror at the savage beatings by inmates of their former Nazi masters. Then there was the question about number of summary executions of Nazi Waffen SS and Camp staff Troops by outraged US troops.

Eichhorn told of the extreme measures to control inmates hunger and dangerous food engorging that included shooting at the legs of violators. Zaid told the story that following the War he encountered a former Dachau inmate who had been shot in the leg for violating food restrictions. In his JWB report, Eichhorn reported:

The doctors ordered me to see to it that no inmates got out of the sections in which most of the Jews were quartered. Armed guards were placed around the fences to make sure that this order was obeyed. Some of the inmates were still bringing food they had ‘liberated’ in Dachau back to the compound. Finding the gates locked, they would scurry up to the fence, throw the food parcels over the fence to those on the other side and then quickly scurry away. I was told by the medics that this would have to be stopped. I instructed the guards to frighten away the food-bearers by shooting over their heads.

This worked quite well for a while, but, when the food-bearers discovered that the soldiers were not aiming directly at them, they continued their well-meant but harmful tactic. Reluctantly I was compelled to tell the guards that they would have to actually hit one of the offenders in a non-fatal spot on his anatomy in order to protect the health of those in the compound. This was done. The next fellow who tried to throw food over the fence got a well-aimed bullet through his leg, was taken off to the hospital and eventually recovered from the wound. This drastic measure halted all further efforts to get any more food over the fence …

Zaid told of a legendary encounter of his grandfather with SHAEF Commander General Eisenhower and General Patton. Patton allegedly criticized Eichhorn he found driving his own jeep instead of using an assigned driver. Eisenhower was alleged to have told Patton, “you can’t talk that way to my rabbi.”

Zaid commented that his grandfather was rather close mouthed for many years following his return from WWII to talk about these experiences. It was left to both Zaid and Greg Page to edit his grandfather’s letters to his wife Zelda and the archives of his NJWB reports to produce a record of Rabbi Eichhorn’s wartime service record and accomplishments befitting a “fighting rabbi.”

Watch Mark Zaid’s presentation about his grandfather at the National Museum of American Jewish Military History in Washington, DC.

Table of Contents

Jerry Gordon is a senior editor at New English Review and co-author of Genocide in Sudan: Caliphate Threatens Africa and the World.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast