Gratitude and Grumbling

by Theodore Dalrymple (July 2019)

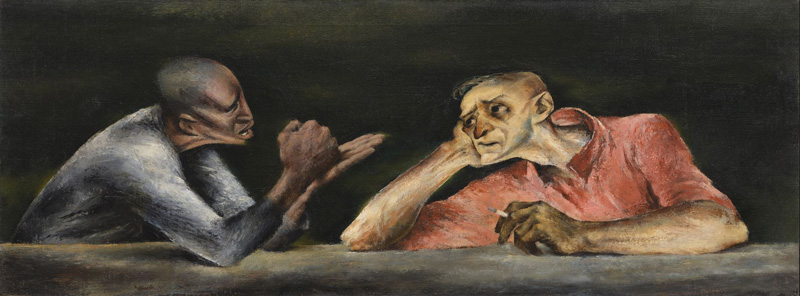

Two Men, Joseph Hirsch, 1937

Gratitude is not the first characteristic of the modern age, however much we may have to be grateful for. Indeed, I have myself made something of a literary career, such as it is, by grumbling. My carping criticisms have covered a wide range of deficiencies and faults, or perceived deficiencies and faults, of both the world and its inhabitants. The fact is that I enjoy complaining. I had an aunt who, when asked how she was, replied ‘Mustn’t grumble,’ but the tone of whose reply was itself a contradiction of the very words uttered. Her saving grace, however, was that she was always aware of the irony and often laughed at it. Without complaint, however, most of us would have nothing to say.

I am nevertheless increasingly aware of how fortunate I have been in life. Without having been born to any great or exceptional privilege, I have never suffered so gross an injustice that my whole life has been adversely affected by it. Such injustices as I have suffered have been petty and of the right dose to strengthen rather than to destroy. I haven’t even had any great misfortunes, and though I have sometimes followed foolish paths (as surely most of us have at some time in our lives), I haven’t even had to suffer unduly financially for my foolishness. Nor have I suffered great misfortune such as many have suffered.

When I look out of my window in Paris, I see a man with severe Parkinson’s disease shuffling by on his daily walk in ever more rapid tiny paces, prevented from falling by a nurse who holds on to him. Of course, my life is not yet over and it is possible that I will develop some such a horrible disease in the future, but so far I have escaped it, and all my illnesses have been curable.

Read more in New English Review:

• Wilted Laurels (or, A Sad Ballade to Our Poets Inglorious)

• The Welfare State

• Hollywood

When I walk to the Métro station about three hundred yards away, there is a lady there aged in her late sixties (I should estimate) who sits by the steps at the entrance with her hand cupped for alms. It is obvious to me that she is a chronic schizophrenic, for she makes the involuntary movements that arise as a side-effect from taking the drugs used to treat that fell condition. I give her a little money each time I see her, which she receives with only the faintest of acknowledgments, the drugs having suppressed her facial expression along with (one supposes) her symptoms.

It is curious that whenever I see these three unfortunates, I feel a curious and pervasive, though not a very strong, sense of guilt. And this is odd because I have no personal responsibility whatever for any of their misfortunes.

The man with anorexia nervosa, in so far as his condition is, or at least started as, a psychological one, might be held responsible for his own misfortune. If he is now in physical danger, it is because he has chosen, or initially chose, a worthless narcissistic goal, namely that of being as thin as possible. It is always possible, of course, that at some time in the future a purely physiological abnormality will be found to account for his strange choice of goal, but it is also possible that none will ever be found.

Be that as it may, sympathy is due to him as a man who suffers (he certainly looks thoroughly wretched). If we withdraw all compassion from those who, to some degree or other, bring their suffering on themselves, we shall not display much compassion in this life because a very large proportion of human suffering, especially nowadays, is self-inflicted: nor shall we ever be the object of such compassion should we need it. And I have little doubt, incidentally, that this man, on the assumption that he has loved ones such as parents and siblings, inflicts considerable suffering on others, for there are few tasks more tiresome, frustrating and infuriating than trying to get an anorexic to eat, or even than merely trying to understand his obsession. For the mother of an anorexic, in particular, life becomes a prolonged nightmare which the anorexic, in his or her self-obsession, fails even to recognise or tries to ameliorate. He or she is self-obsessed.

I compare my life with theirs. It is infinitely more fortunate, but not through the exercise of any virtue of my own. I could easily have had a life as wretched as theirs without having done anything to deserve it. I have simply had good luck.

But luck, either good or bad, has nothing to do with desert, and good luck is therefore not the proper object of guilt even when one is surrounded by people who suffer bad luck. It is not my fault that I do not suffer from Parkinson’s disease while my unfortunate neighbour does. It might be that one’s feelings are not ruled entirely by logic—that it is possible to feel guilt for what one is not responsible—but I nevertheless suspect that my guilt arises from something else.

My constant carping about the state of the world has the effect of disguising from me how fortunate I have been, and how fortunate I remain: though this, of course, could change by tomorrow, or indeed in an hour’s, in a minute’s time. As Donne put it:

For health in this passage we might substitute life itself, for health is not the only thing that can go wrong in an instant, and bad health is not the only thing that can summon us, seize us, possess us and destroy us in an instant.

I feel guilty in the face of such misfortune as I have described because I am not sufficiently cognisant of or grateful for my good fortune. I take it for granted, as my due, when it is not my due at all—not that I think I deserve worse fortune either. I complain bitterly at minor inconveniences (despite my frequent resolutions never to do so again), when I do not have to go very far, or search my memory for very long, to find infinitely worse suffering borne with noble fortitude by others. My ingratitude for a moment appals me.

I acknowledge that a faith in such a benevolent design is or can be extremely helpful to those who bear the brunt of misfortune. To believe that one’s suffering has a purpose, that it not entirely meaningless, can reduce its intensity. But what is psychologically desirable or beneficial is not necessarily true. Indeed, many things are desirable that are not true. The belief that there is a benevolent design can console us only if we believe that there is in fact such a design. One cannot truly believe something because one knows it would so one good to do so.

I find it impossible to believe that the universe has any particular attitude to me: that by conferring upon me my good fortune relative to others, for example, it is expressing its best wishes towards me. If it did have such an attitude, it would presumably have a malevolent attitude to others, for reasons best known to itself. The same is true of God. I believe none of this.

And yet, notwithstanding all that I have said, I think it right to express my gratitude and still feel guilt in the face of the misfortune of others. This suggests to me that, as Pascal put it, the heart has its reasons that the head knows not of.

This brings men naturally enough, to the difficult question of the metaphysical foundation or justification of our moral feelings and judgments. Human life itself decrees that we make such judgments, and that we cannot escape making them. When people claim that they are non-judgmental, they are generally preening themselves on their moral superiority to those who admit that they make judgments.

Read more in New English Review:

• We Will Not Go to Mars

• From the Magical Land of Ellegoc to the First Man on the Moon

• Slavery is Wrong, How Can Abortion Be Right?

But if such judgments are unavoidable, the philosophical basis on which they are to be made seems to me far from clear. In my opinion, religious belief does not really help. The belief that God’s laws, even supposing that they can be known in any detail, ought for moral reasons to be followed must rest on the belief that God and His creation are good, in which case the apprehension is antecedent to any knowledge of what God decrees, and it is therefore for us to decide unaided by belief in Him. But no other supposed basis of moral judgment is satisfactory, either. To argue, for example, that the process of evolution has furnished us with a moral sense, even if true, is of absolutely no use in making a particular judgment. Appeals to evolution cannot answer the question of whether I ought to help an old lady across the road. To say that x is good cannot be reduced to a statement about what natural selection, or indeed any other quality of the world, supposedly decrees for us.

This is what happens once Man has eaten the fruit of the tree of metaphysics.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Kenneth Francis) and Grief and Other Stories from New English Review Press.

NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast