by Norman Berdichevsky (February 2025)

As recently as the outbreak of World War II, the Danish Realm consisted of four distinct segments: Denmark proper (the peninsular of Jutland located on the mainland of Europe and sharing borders with Germany and two major islands, Zealand, and Fünen), and three outlying island regions with major geographic barriers separating them from Denmark proper and often referred to as “Arctic Denmark,” namely Greenland, the Faroe Islands and Iceland (see map below).

In 1944, Iceland separated itself and became a distinct independent nation under the temporary protection of American and British forces; In September, 1946, the population of the 18 Faroe Islands were granted a plebiscite to decide on their future status. The result of the vote was a tiny majority of 51% for independence, 5% invalid ballots and 2% abstentions.

The Danish authorities rightly judged that such a miniscule “majority” was not a sound decision on which to take such a fateful political decision and wisely held a “do-over.” Two months later with more attractive guarantees for local rule, provision of its own flag and guarantees to preserve the Faroese language in education. These measures satisfied many of the former independence minded voters who then supported an autonomous status within the Danish kingdom. World attention took little notice of these events in Iceland and the Faroes but the current sudden eruption of interest in Greenland, the largest island in the world, possessing immense strategic value as a changing climate portends access to new advantageous shipping lanes, plus an abundance of mineral wealth. These prospects coupled with the recent headline grabbing remarks of President Donald Trump bout American purchase or seizure have created a radical new situation. It makes the eventual outcome of a new Danish geopolitical drama the subject of intense speculation.

Even the slight change in the monarchy’s formal coat of arms ordered by King Frederick X that slightly increased the size of the polar bear (representing Greenland), became the subject of considerable comment in the world press.

Denmark and Greenland could not be more different from one another. Geologically, climatically, biologically, and culturally, Greenland is much more similar to North America than Europe. The native Inuit peoples (formerly called Eskimos) of Greenland and northern Canada are related and speak closely related languages. Greenland’s interior ice cap, which covers the greater part of the island, measures up to 3,000 meters (10,000 feet) in thickness. Underneath, lies the Greenland Shield, a mass of ancient hard rock, mainly gneisses and granite.

Danes occasionally like to tease foreigners, especially Americans, who are notoriously deficient in geographical knowledge, by asking the question “What is the largest country in Europe?” and then aggressively responding, “Why Denmark, of course!” Although Greenland has been an autonomous part of the Danish Kingdom since 1953, it is roughly fifty times the size of Denmark proper. However, Greenlanders opted out of membership in the European Union in 1982 shortly after Denmark joined, thus stressing that although part of the same country officially, Greenlanders wish to preserve much that is uniquely their own.

What all foreigners recognize as “Denmark proper” is only one part of the Danish Kingdom. The other two components—Greenland and the Faroe Islands—have their own flag, language, distinctive history and traditions and both were former colonies where some resentment against the Danes still lingers.

Lying mostly north of the Arctic Circle, Greenland (Greenlandic: Kalaallit Nunaat; Danish: Grønland), is an island that enjoys home rule that put an end to hundreds of years of direct colonial rule from Copenhagen. In a referendum in 1979, Greenlanders voted to manage their own internal matters. Both Greenland and the Faroe islands have two seats each in the Folketing (national parliament) and small populations of between 50,000 and 55,000. Only foreign affairs and defence remain completely under the control of the central government in Copenhagen. Local executive power is held by a seven-member body, the Landsstyre.

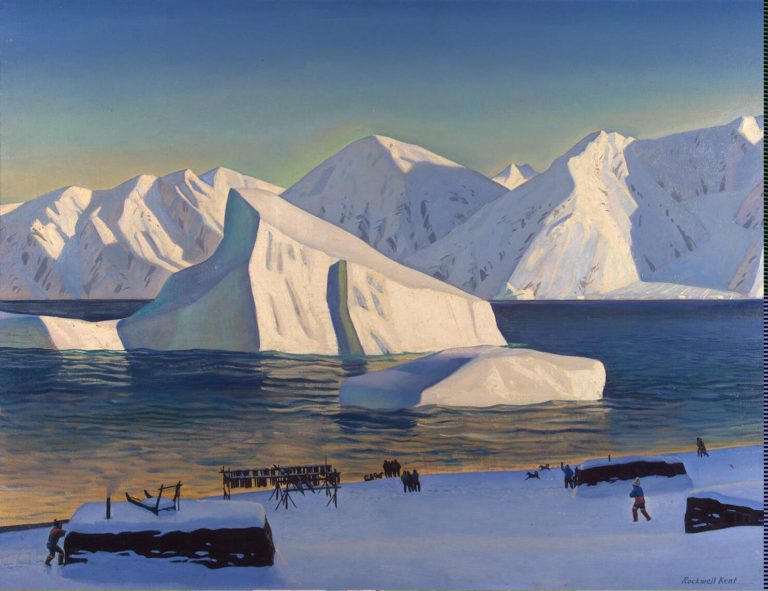

Agriculture has hardly been possible, even on the tiny coastal belt in the southwest although it is believed that when the first Viking settlers arrived in the 11th century, the warmer climate prevailing then made agriculture and sheep grazing possible on a considerably greater scale than in more recent times. The main livelihood has always been fishing and hunting whales, seals, reindeer, polar bears and musk-ox. Most townspeople work in public services. There is limited tourism during the summer season for the “hardy outdoor types” from Denmark but it is quite expensive. All who have been there will tell you that the spectacular scenery makes it well worth it.

The Greenlanders are primarily Inuit and mixed-European, especially Danish-Norwegian. The overwhelming majority of the population is located on the narrow southwestern coastal fringe.

History

How did the Danes get to Greenland? They didn’t! Labrador, Newfoundland inland, and Greenland—like the Faroes and Iceland—were discovered during the westward exploration of Viking seafarers (Eric the Red and Leif the Lucky) who sailed mostly from Norway. Greenlanders are racially distinct from ethnic Danes although many are of mixed race and now increasingly demand to make full use of their rights. Their opt-out from the European Economic Community ensured that access to traditional fishing (primarily cod, shrimp and salmon) and hunting grounds as well as its mineral wealth are protected. Denmark is still Greenland’s largest trading partner and receives much of the island’s catch of fish, as well as hides and skins.

Danish control of the North Atlantic stepping stones to America was the result of absorbing Norway and its overseas settlements in Iceland. The Black Plague had devastated Norway in 1349 and left Norwegians no choice but to seek Danish protection. By that time, very severe cold winters had already wiped out the old Norwegian Viking settlements in Canada and Greenland initially established about the year 1000. Much later, in 1721, the Danes revisited Greenland and founded their own Cape of Good Hope colony (Godthaab, or Nuuk, the capital). Originally motivated to find the descendants of the original Viking settlers and convert the ‘heathen,’ Danish monarchs subsequently dreamt of a Danish empire stretching across the Atlantic to the Caribbean, where they were able to purchase three small sugar rich islands in the late 17th century that became known as the “Danish West Indies” (known today as “The American Virgin Islands”).

Many Greenlanders are critical today of Denmark’s former commercial policies that exploited the island’s resources when still a colony. Whale oil for use as a lubricant in the textile industry and in street-lamp lighting was an important raw material that enabled Danish capitalism, commerce and industrialization to make great strides. The local Inuit who had only hunted whales for consumption were brought into the modern industrial world economy and encouraged to kill as many as possible in exchange for modern consumer goods, especially tobacco and alcohol. Europeans brought venereal disease and alcohol which caused havoc among the Inuit. What had been a largely egalitarian society became a class-divided one with better and more successful whalers encouraged to invest in new equipment and boats.

“Border conflict” with Norway

The KGH (initials in Danish for den Kongelige Grøndlandske Handel-the Royal Greenlandic Trade Authority, a government monopoly) dominated all trade with the local population in a “company store” arrangement. The KGH stores became the most important factor in the lives of the native Inuit people and brought about a concentration of the population in their vicinity. Almost all administrative, health, educational and social work was carried out by Danes who typically came for a period of a few years and then returned home.

Although Danes are not proud of their past colonial treatment of the Greenlanders, few feel that Denmark deserves continued criticism. Most reject the idea that Greenland should dissolve its union with Denmark. It is for these reasons that the issue of a final settlement of the country’s political status is still controversial and, inevitably, as President Trump has emphasized, Denmark provides enormous subsidies of more than $100 billion yearly in addition to the military protection of membership in NATO. It is a logical question to explore how an independent Greenland would manage without a similar reliance on the United States. Similarly, how would it provide for its own defence?

When Norway (which also had been under Danish rule for centuries) finally re-established its independence (from Sweden) in 1905, claims were made to regain at least part of Greenland that had been chartered and settled by Vikings from Sweden. This simmering dispute later erupted into the most serious “border conflict” among the Scandinavian states in the 20th century. In May 1921, Denmark declared the entire island of Greenland “Danish territory.” Norway insisted that this violated its traditional hunting and fishing rights along the east coast and argued that prior discovery by Norwegians entitled it to claim at least part of the island.

The issue was finally settled by the Permanent Court of International Justice at The Hague in 1933, which decided in Denmark’s favor.

The United States had also promised to support Denmark’s claim in 1917 when it purchased the Danish West Indies (today’s Virgin Islands) and relinquished its own claim to Northern Greenland based on the explorations of the American polar explorer Robert E. Peary. So, from the American point of view, Denmark already owed the United States a favor.

It was during World War II that a decisive break was made with Denmark as a result of the German occupation of Denmark, and the strategic importance of Greenland emerged. Greenland would play decisive roles both in the battle for the Atlantic and the Allied invasion of occupied Europe, although few were aware of this on April 9, 1940, when Denmark surrendered to Nazi Germany. Many Danes looked in astonishment and disbelief at the abject surrender of its armed forces within four hours after the German invasion!

It lay only in the power of thousands of Danish seamen and the Danish diplomatic corps abroad to continue the fight. Many Danish crews and captains of scores of fishing vessels and cargo ships sought to reach American and British ports rather than return to an occupied Denmark. Denmark’s ambassador in Washington, Henrik Kauffmann, refused to heed his government’s orders and publicly announced that he would represent “Free Denmark unoccupied,” explaining that the king and the government had been coerced. He offered the American government the right “to construct, maintain and operate such landing fields, seaplane facilities and radio and meteorological installations in Greenland as may be necessary.” American air bases in Greenland were vital in the struggle against German submarines preying on Allied convoys of supplies to Britain and Russia.

D-Day landings

Joint Danish-Greenlander sled patrols drove off expeditions of German radio technicians and meteorologists attempting to gain vital weather information. A “Free Denmark” in Greenland and the Faroes enormously raised the spirits of Danes at home and won the support of other Danish ambassadors. The government in Copenhagen officially declared that Kauffmann was acting illegally (after the war he was decorated for having defied orders). Nevertheless, most significantly, the local authorities in Greenland voted to follow him rather than the instructions from Copenhagen. Greenland was vital for the protection of Allied convoys and for early meteorological reporting and the secret to the successful D-Day landings on June 6, 1944, when the Germans, without such facilities, were unaware that the stormy weather in the North Sea, that made an invasion unlikely, had abated.

Postwar Greenland

The war convinced many Greenlanders that the paternalistic authorities in Copenhagen did not “always know best” and gave them the first real taste of deciding things for themselves. The result was the formation of a new political force determined to win a measure of autonomy and end the long relationship of a remote colony that simply supplied raw materials to the mother country.

In May 1947, Denmark requested a formal agreement with the United States over the use of bases in Greenland. Arduous negotiations culminated in April 1951, providing for Danish control of the chief U.S. naval station in Greenland and for the establishment of jointly operated defence areas. Later, the U.S. Air Force, operating under the NATO command, built a huge airbase in Thule in the far north. This was the most important advanced early-warning station for possible Soviet missile strikes against the United States. Demands for autonomy were gradually met by a new Danish constitution in May 1953, when Greenland became “an integral part of the Danish monarchy” and obtained representation in the Folketing.

An irritant in relations between Greenlanders and Danes for generations has been the inequality in standards of living, education and wages. Although the Danes have always prided themselves on the absence of great gaps between the “haves” and the “have-nots” and maintain one of the highest tax burdens in the Western world (designed to provide welfare benefits), it has not been possible to enforce a formal equality with its former colony. In order to entice Danes to live and work in Greenland, it has been necessary to offer much higher salaries than the state can afford to pay Greenlanders.

Many Danes believe that even with much good will, there are sharp differences in outlook, sense of responsibility and “mentality” with Greenlanders that are difficult to overcome. It is a story that has also occurred elsewhere—the transition from a hunting and gathering economy to an industrialized and bureaucratic society. Greenlanders are still dependent on (and resentful of) so many Danes who continue to be needed in such sensitive areas as education. Debate and doubt still cause unrest among Greenlanders that, while their language has been recognized, there is little to read in it and that “home-rule” is a nice name but they are still poor distant third-world cousins.

They question What is authentically Greenlandic? in their society where the same Danish-style administration, education, legal and penal systems, health services, political system and social welfare policies characterize everyone’s daily existence. Many have had great difficulties in making the transition from what was the universal traditional form of accommodations in Greenland, single-family dwellings at ground level, to multi-storey apartment blocks.

The best-selling novel by Danish author Peter Hoeg, Smilla’s Sense of Snow, dramatically exploits the native Greenlanders’ skills at survival and understanding of the arctic environment. The book was made into a film that received mixed reviews for its acting and plot but universal praise for its beautiful photography of the Greenland environment. Smilla is a mixed Inuit-Danish girl living in Copenhagen who has not forgotten the traditional skills learned as a child in Greenland. Her “sense” for snow and ice are critical in the unfolding of the mystery. The Copenhagen detectives simply judge a boy’s death as an accident. He must have slipped on the snow and fallen from the roof to his death, but Smilla’s sense of snow (Greenlanders have a hundred different words for snow and ice) make her doubt this explanation. The book and film reawakened the interest of many Danes in Greenland, part of their own country yet still distant and so totally different.

Table of Contents

Dr Norman Berdichevsky is the author of An Introduction to Danish Culture.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

4 Responses

Good get, Norm. Interesting and timely. My ancestors, on my father’s side, come from Trinity Bay, Newfoundland. I’m sure you know the Inuit migrated from West to East. Greenland natives had/have always had more in common culturally with Labrador than Denmark, Sweden, or Norway. Sadly, modern Canadians (Anglophiles/ Francophiles) don’t treat the indigenous peoples of Labrador any better than Scandinavians treat their Inuits. Somehow these hardy, remarkable people, wherever they reside, always seem to get the short end of the stick.

A fascinating and compelling deep-dive into the history, culture and underlying issues related to the recent Trump Administration interest in making Greenland (under potential American sovereignty) great again. Thanks to Norman Berdichevsky for this eye-opening reveal!

Good, informative essay, but I am given to wonder, not to diminish the main theme, whether the Inuits could not be gifted with beachfront properties in Gaza, at taxpayer’s expense, of course, in exchange for American military access to the island?

A beautifully woven history of Greenland by Mr. Berdichevsky which sheds light on the current political discourse between the U.S. and Denmark. The author deftly illustrates how different the Danes are from the inhabitants of its northern territory, a combination of native tribes and Norwegian and Swedish based settlers who have Viking blood. The two are culturally, educationally, and economically at odds and have a very thin legal connection which could be breached with some negotiations. Denmark’s speck of land in northern Europe with Greenland have more land mass than any other European state, which is astonishing. Greenland holds vast amounts of natural resources that have yet to be exploited and militarily are key to the U.S. and world security against the Soviets. Thank you Norman for your timely work.