Guru

by Jillian Becker (March 2023)

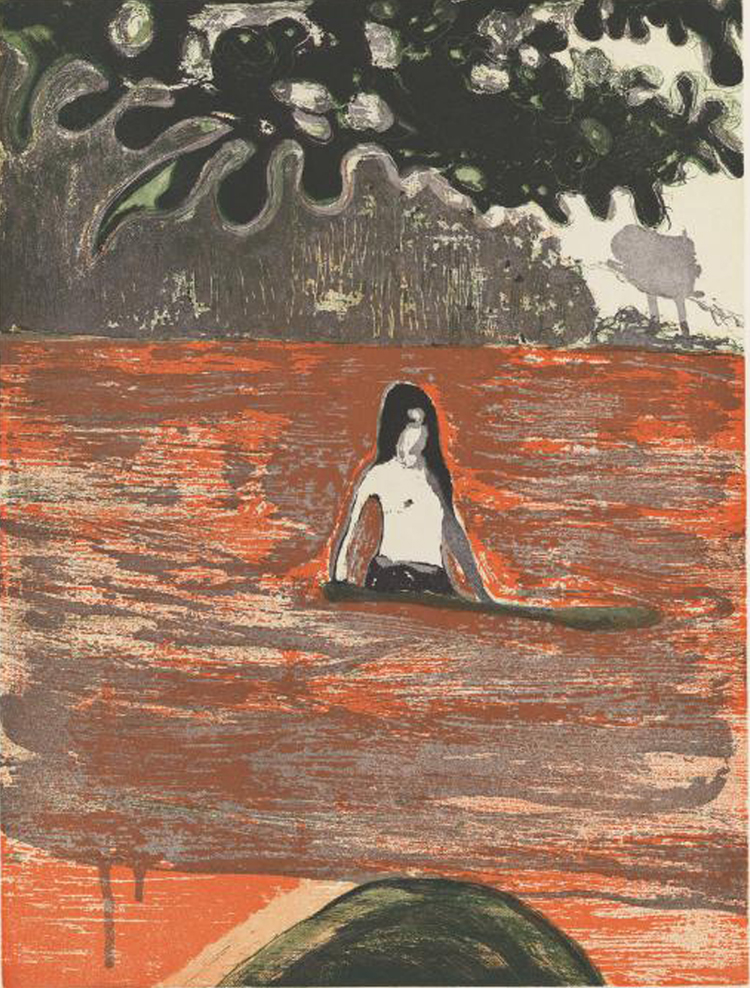

Paragon, Peter Doig, 2005

Chelsea Ellman, whom I met once or twice in New York through her cousin Leonie Lunet, went to live on an Ashram in India. When she had been there for nearly two years, she emailed Leonie asking her to meet a guru named Wensley, who was flying from Delhi into Kennedy International Airport the next Sunday, and to put him up for a few days.

He arrived wearing two sheets, sandals, black-rimmed spectacles, carrying a bulging briefcase, and smoking a cigar.

On the drive to her house, Leonie asked him for news of Chelsea and a description of life on the Ashram. He answered laconically. ‘Oh, she’s just fine.” And, “It’s quite peaceful.” Miles were covered without a word passing between them. She wanted to ask him how long he would be staying, but didn’t. She thought it might make her sound inhospitable.

When he unpacked the briefcase in her guest room, she saw what it had borne across the sea: another sheet or two, his Canadian passport, and two boxes of duty-free cigars.

Her father Leon was staying with her at the time while her mother was away on an all–women cruise with a group of old school friends. Leon too tried to get information and opinion out of Wensley, but the guru revealed little more about himself than that he would need privacy to see “a few pilgrims” while he was in New York.

Father and daughter talked mostly to each other at meal times, trying now and then to get Wensley to join in. Sometimes he did, briefly.

He did not eat meat. His brown rice and uncommon vegetables had to be cooked a special way.

He helped himself to cigars from a box Mr. Lunet generously left on the coffee-table.

His meals were cooked and his sheets washed and ironed by Carmen, the daily help, who had immigrated illegally from Nicaragua. She also made his bed, cleaned his room, and ran errands for him.

Sitting cross-legged on a Bokhara rug in Leonie’s living room, he dispensed wisdom between two and four o’clock to those who came to him to receive it. Leonie got to know that they included a suicidal feminist recently divorced, an alcoholic newspaper reporter, and a nineteen-year-old transgendered drug addict from South Korea. And she knew they paid him, though not how much. She had seen the banknotes in his hand.

She asked him not to receive clients in that room on weekends. “Sure,” he said.

When he had smoked all Mr. Lunet’s cigars, he asked for more. Mr. Lunet replied with an amiable laugh that he, Wensley, had consumed his whole month’s supply, and suggested that he, Wensley, might go out and buy some more for them both. Wensley joined in the laughter, but did not buy cigars.

One Saturday afternoon Leonie had few women friends over for tea. Her father said he would “leave them to it” and went out, but Wensley joined them. He moved an antique Spanish armchair to a place in front of the window. Sitting with his back to the light, his face was in shadow. After Carmen had brought in the tea and cake and withdrawn, Wensley gently rebuked the gathering, at some length, for “exploiting Hispanic immigrant labor,” as he sipped his tea and forked cake into his mouth. He told them they were parasites. Though he did not raise his voice, he used cuss words, taboo words, in almost every sentence. The guests were too polite or too liberal to give the least sign of taking offense.

One day Chelsea telephoned from India to find out if Wensley was happy. Wensley couldn’t talk to her because he was closeted with the alcoholic newspaper man and was never to be disturbed at work. Leonie said he was happy, but she and her father less so. Chelsea suggested they take Wensley out to entertainments, to games, to Indian restaurants.

That evening, as a storm was breaking, the thunder loud, the lightning brilliant and frequent, Leonie, alone with Wensley, asked him when he planned to go. Wensley said, ‘If I’m not wanted here I’ll go now.”

He stood up, lightning lit up the windows, thunder cracked, and the rain came down hard and noisy.

“Perhaps you would lend me an umbrella,” he said.

“Where will you go?” Leonie asked. “You have nowhere to go. Though I suppose you have enough money for a hotel.”

He replied, “I have the rain to go to. I have the sky, the thunder, the lightning. If there are hailstones, they might teach me something new.”

He went up to his room but he did not leave the house.

When the storm was over, Leonie telephoned Chelsea’s brother Jeff and told him she was bringing his sister’s friend Wensley, visiting New York from India, to stay with him.

Jeff did not look surprised when Wensley walked into his apartment wearing sheets. The next day he emailed Leonie to bring Wensley’s special foods and some cigars. She would take nothing to Wensley, but had a supply of groceries delivered to Jeff’s apartment, and enough cigars for a week, as she imagined.

Three days later an email came from Wensley himself asking for more food and more cigars. She had the first order repeated. A few days after that, Wensley fell ill and Leonie sent him a doctor and the medicine that the doctor prescribed—for all of which she paid.

He did not let his pilgrims know where he was. Leonie gave the reporter and the South Korean the address as each turned up to be met with disappointment. The divorced feminist did not come. Perhaps, Leonie thought, one of the other pilgrims told her he had moved, and perhaps she felt deserted by him, and perhaps she committed suicide. And it troubled her slightly that she herself might be the indirect cause of an act of despair by sending Wensley away.

Eventually Wensley was exported. Jeff bought him the ticket and took him to the airport. He asked Leonie to reimburse him for the ticket. She did. She did not ask Jeff whether the guru had flown back to the Ashram or home to somewhere in Canada. The cost of the ticket suggested India, but he might have insisted on first class to Toronto.

Chelsea emailed Leonie to say she was personally hurt that they had treated her friend so unkindly.

“Such a rare being,” she wrote. “He could have done so much for all of you blind materialists if you had let him.”

Jillian Becker writes both fiction and non-fiction. Her first novel, The Keep, is now a Penguin Modern Classic. Her best known work of non-fiction is Hitler’s Children: The Story of the Baader-Meinhof Terrorist Gang, an international best-seller and Newsweek (Europe) Book of the Year 1977. She was Director of the London-based Institute for the Study of Terrorism 1985-1990, and on the subject of terrorism contributed to TV and radio current affairs programs in Britain, the US, Canada, and Germany. Among her published studies of terrorism is The PLO: the Rise and Fall of the Palestine Liberation Organization. Her articles on various subjects have been published in newspapers and periodicals on both sides of the Atlantic, among them Commentary, The New Criterion, City Journal (US); The Wall Street Journal (Europe); Encounter, The Times, The Times Literary Supplement, The Telegraph Magazine, The Salisbury Review, Standpoint(UK). She was born in South Africa but made her home in London. All her early books were banned or embargoed in the land of her birth while it was under an all-white government. In 2007 she moved to California to be near two of her three daughters and four of her six grandchildren. Her website is www.theatheistconservative.com.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast