by David Wiener (August 2023)

Two on the Aisle, Edward Hopper, 1927

Two of the greatest American plays ever written were such immediate, huge hits on Broadway it’s hard to believe they both groped and stumbled their way to classic status.

Not many plays—not even many hit plays—can be called classics, but “The Odd Couple” and “A Streetcar Named Desire” are definitely two of them. Both had a long, hard, uphill climb before they opened (and “Streetcar” only found backers because of the producer’s family connections).

“The Odd Couple” opened in 1965 and “A Streetcar Named Desire” opened in 1947—but we can still experience something surprisingly close to what those plays were like on stage because both were made into movies and both screenplays ended up being very close to the original play scripts. (In “Streetcar’s” case, there was a big flap over toning down some of the racier lines and scenes but when the shouting was all over, many of the changes demanded by the censors had been largely ignored.)

Neil Simon, probably the 20th century’s most successful rewriter and script-doctor, wrote “The Odd Couple” and Tennessee Williams wrote “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

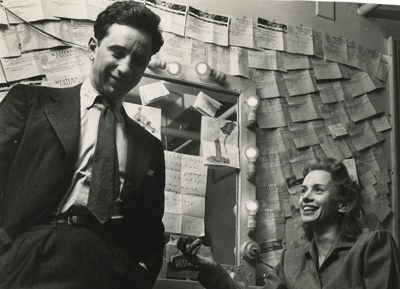

Neil Simon started out as a radio and TV gag-writer, most notably for Sid Caesar’s “Your Show of Shows.” By 1957, he was out in California writing for TV when he decided to make his move into theater, something he’d wanted to do for quite awhile. He called his first serious effort “One Shoe Off,” which became “Come Blow Your Horn.”

“The longest thing I had written up to that point was 12 pages,” Simon remembered, “because that was the standard length for a TV variety sketch in the 1950s.” A play in those days was expected to be ten times as long, three full acts. And the last thing Simon expected to do was write a second, third, or fourth draft. A few minor changes here and there—but entirely new drafts? They never did that in TV. They didn’t have time to do that in TV. Eventually, “Come Blow Your Horn” would take a year to write and almost three years to rewrite: 22 complete revisions, starting with page one each time and all of them done in Simon’s spare time from TV writing.

By 1959 Simon was up to draft number 18 and decided it was time to send “Come Blow Your Horn” to his agent at William Morris. His agent sent it to Herman Shumlin who was one of Broadway’s busiest director/producers in the 1950s, a real theater big shot. Shumlin produced his first play in 1927 and somehow even found time to direct two movies.

Shumlin liked “Come Blow Your Horn” —as a series of funny lines and jokes, but not as a play. However, he was willing to work on it with Simon, an event which changed the playwright’s life. There was an awful lot of stumbling and plenty of false starts. Shumlin offered Simon the same advice Irving Thalberg gave the Marx Brothers (which saved their career): In comedy, especially popular comedy, it’s important to make the characters likeable. Otherwise, the audience won’t connect with them and live their story with them. They won’t root for them as they go through all their troubles. (“The Big Bang” is a recent example; viewers cared about those characters and what happened to them.)

A few rewrites later Shumlin dropped out, but another successful producer stepped in and made some helpful suggestions—a man named Max Gordon.

Gordon was the archetypal cigar-chomping play producer. Again, there were more rewrites as Gordon coached Simon on construction. He told Simon that “a play is like a house, it needs a solid foundation. What you’ve got here is still built on sand.” And that was it for Max Gordon; he left the project.

Simon’s great advantage through all this was his agent at William Morris, Helen Harvey, who was able to arrange tutorials on improving his script from, among others, heavy-hitters like David Merrick, Garson Kanin, and Arnold Saint Subber.

Saint Subber started out as an office boy in the Shubert organization and hit it big with “Kiss Me, Kate” in 1949. Saint Subber liked “Come Blow Your Horn” and wanted to produce it. “Not only had I met a Saint,” Simon remembered, “I was about to enter the gates of playwright heaven.” Only to be cast out of paradise. After an intensive rewriting tutorial that lasted about four months, Saint Subber also decided to pass on “Come Blow Your Horn.”

Simon—and his well-connected agent—kept hammering away. They finally managed to make a very valuable connection to producers Mike Ellis and William Hammerstein, the son of Oscar Hammerstein.

Ellis owned the Bucks County Playhouse and produced the much-rewritten “Come Blow Your Horn” as a summer-stock show in front of a real, live audience, hoping to get backers. They raised a total of $300.

Ellis and Hammerstein gave Simon six months for more rewrites—and they’d pay him the $300. Grateful to have feedback from a live audience, Simon set to work yet again.

“It’s one thing to be willing to rewrite,” Simon said, “you have to be able to rewrite.” Eventually, he had to force himself to stop. He knew the script was improving, but he was afraid he’d “rewrite it to smithereens.” And so, the script went back to Hammerstein and Ellis, who decided it was good enough to put on stage again.

They tried the play out in Philadelphia at the Walnut Street theatre—their goal was to take it all the way to Broadway. On the opening night of the Philadelphia tryout, a man died of a heart attack in the balcony. Really. It’s in Simon’s book. Some poor guy actually keeled over and died.

But the theatre business, being extremely weird, is not necessarily cursed by things like that. The out-of-town tryout of “Come Blow Your Horn” was a success, both with audiences and the critics. So, the next step was the Brooks Atkinson Theatre on Broadway.

Now, Simon certainly wasn’t facing homelessness if his playwrighting career didn’t pan out. The worst that would happen is that he would go back to California and TV writing, which wasn’t exactly a ticket to the soup kitchen.

But mentally and emotionally, he desperately wanted to make a living—and a name—as a playwright. Maybe it had something to do with outshining his brother Danny, a highly successful television writer who had mentored Neil and frequently collaborated with him on TV scripts. “Come Blow Your Horn” might be Neil’s first and only chance to become a big name on his own.

The play opened in New York on February 22, 1961 and nobody dropped dead. In fact, people laughed. Lots of them; but the critics only grinned. At the opening night party at Sardi’s, Simon didn’t have his invitation and the doorman wouldn’t let him in.

“Look, I don’t need an invitation,” Simon said, “I wrote the show.”

“That’s your job,” the doorman said. “Mine is to let in only the people with invitations.” Simon and his wife had to wait until they were brought inside by one of the actors.

The mixed reviews pretty much killed ticket sales the next day, so the producers decided to paper the house—give tickets away—for about a week, hoping word of mouth would overcome the reviews so they could get back to actually selling tickets.

The first night of free tickets brought in an audience of about 300 to the 1,000 seat theatre. And, no matter what the critics thought, the audience loved it. The following night, 100 tickets were sold and 400 were given away. Everyone cut back on their royalties and even the theatre owner kicked back some of his take. Still, nowhere near enough tickets sold to keep the show going.

And then Simon got a huge break, a real gift. It came in the form of a glowing mention by New York Post columnist Leonard Lyons, who wrote a regular column called “The Lyon’s Den.”

A few days into the agony of “Come Blow Your Horn’s” slow death, the Lyons column included this item:

Noel Coward looked up from his chili con carne while Irving ‘Swifty’ Lazar noticed that his Eggs Benedict looked like a Picasso. ‘I’ve just seen the funniest play in New York,’ said Noel, ‘Swifty, dear boy, what was the name of it?’ ‘Come Blow Your Horn,’ Swifty said as he cut into his priceless Picasso.

By that weekend, the theatre was two-thirds full and just about all of those seats were occupied by paying customers. A couple of days later, Lyons’ column mentioned that Groucho Marx said he laughed his head off at the play. More tickets sold on the strength of that, and word of mouth continued to build.

“Come Blow Your Horn” ran for two years—oddly enough, usually with the theatre about half full—and was made into a successful movie in 1963.

Simon’s next project, a musical called “Little Me,” didn’t do so well in New York but fared much better in London, something nobody expected from Simon, who wrote very American humor, lines, and situations.

Simon then wrote a hit play called “Barefoot in the Park,” which was also made into a successful film. All this positioned him for what came next—probably his best-known work, “The Odd Couple.” As far as I know, the idea for “The Odd Couple” was his brother Danny’s but Neil Simon wound up writing it and got sole credit in return for giving his brother 10% of the property.

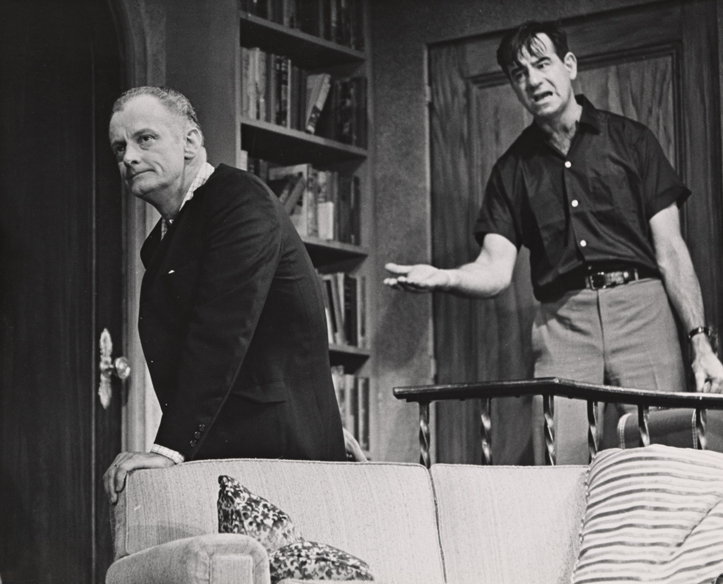

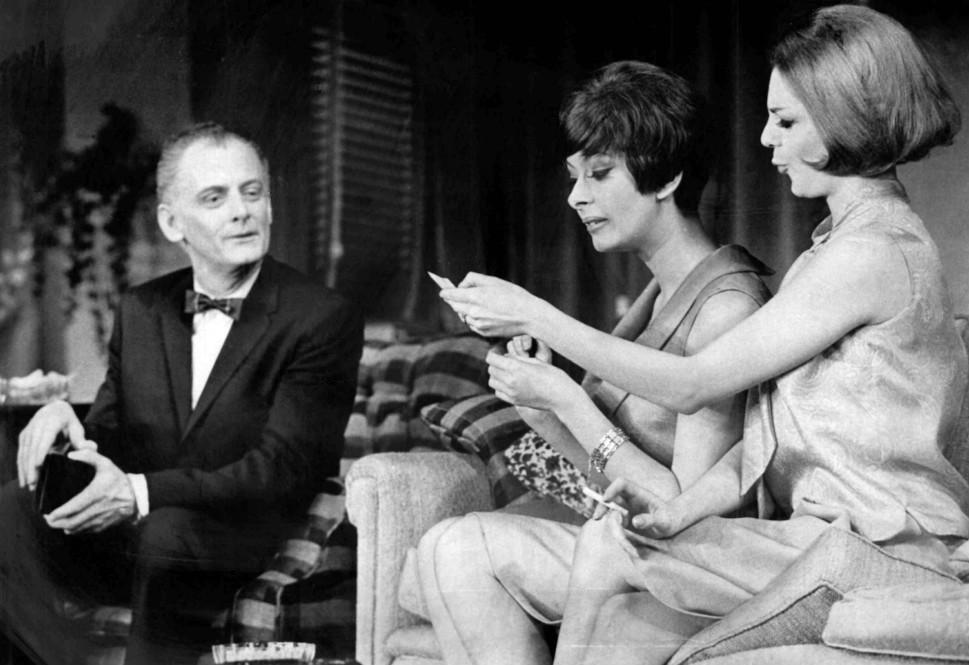

Writing the first act went pretty smoothly—Simon had played plenty of nights of poker with his friends, and that was the basis of the play’s opening. In fact most of the writing went smoothly, to his great relief, so off it went to Saint Subber and director Mike Nichols. Both grabbed it, and the theatre was booked.

Sounds easy, doesn’t it?

Simon loved the idea of Walter Matthau playing sloppy Oscar Madison—he’d seen him playing Nathan Detroit in a revival of “Guys and Dolls.” But Matthau wanted to play neat-freak Felix Ungar, which stunned Simon. Turns out, Matthau wanted to do Felix Ungar because the role would stretch him, it would really require acting. Simon said, “Look, Walter, just do me a favor; go act in somebody else’s play—do Oscar Madison in mine.”

Eventually, Matthau agreed and Art Carney, a much bigger name than Walter Matthau at that time (he was Ed Norton on the hit show “The Honeymooners” from 1955-1956) was cast as Felix Ungar. Shortly after that, the other parts were cast and Mike Nichols sat down with them for the first read-through.

Nichols was confident, but Simon felt uneasy. Soon enough, he found out why; Acts I and II were pretty solid—very good, in fact. But two minutes into Act III, he knew they were in real trouble. “It was,” he said, “unimaginably bad.” The read-through ended in eerie silence. Matthau said he was having second thoughts about doing the show. The cast left for lunch; Simon looked at Nichols and said, “Mike, What do we do?” Nichols said, “Well, I’m going to lunch, then start directing Acts I and II. You’re going to go home and write us a new third act” —while the play was in rehearsal, with a little over three weeks before the first tryout in Delaware, which would be followed by another brief tryout in Boston. Simon walked home in the rain, even stopping to sit for a while in St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Then it was time to go to work.

He put in more than ten hours a day rewriting the entire third act of “The Odd Couple.” Then the actors sat down to read it—and it was even worse.

Simon’s confidence was badly shaken. “I wasn’t blocked,” he said, “I could think of hundreds of things but didn’t like any of them; and the ones I liked, I didn’t trust.” They were about two and a half weeks away from the first tryout. Simon just stared out the window and counted leaves on the trees.

Mike Nichols was now acting strange—a feeling of impending doom will do that to people. He came up with ideas that were just plain peculiar. He decided to have a TV set on during the poker game, complete with sound. “We’ll play a tape of a ball-game while they’re doing the poker-game scene,” he said. Simon couldn’t believe it—he tried to tell Nichols how distracting that would be, the audience wouldn’t be able to hear the lines with a TV set going. Nichols agreed to kill the TV. Then, he suggested cutting out the poker game entirely—one of the best things in the play! The clock kept ticking—and “The Odd Couple” went to the tryout theatre without a new third act.

They brainstormed on the train. Simon wrote around the clock in his hotel room. He had yet another new third act that the actors were given as the set was being put up. They had two and a half days to memorize and rehearse “The Odd Couple’s” new third act. As they say in show-biz, “Dying is easy; comedy is hard.”

Now, by this time, Matthau was wavering between outrage and panic. Nichols told him that they’d all be better off doing a good third act poorly instead of a bad third act well. After all, he kept telling them, it was still a tryout; God willing it’d work by the time they got it to New York.

Art Carney was also having problems, but not primarily with the show; his marriage of 25 years was falling apart and he was dealing with his own real-life divorce, an irony not lost on anyone connected with the production—which was all about divorce.

Matthau was close to a meltdown; on the first day of rehearsing the new third act, he threatened to quit again, but was talked out of it—again—by Mike Nichols.

“OK,” Matthau told him, “but at the curtain call, I’m going to say, “Ladies and gentlemen, I did my best—blame this crap on Nichols and Simon.’” Simon said the rehearsal started to look like a room full of bumper cars.

And then came the first night of the tryout. Acts I and II were great, but the new Act III was far from finished; the show wobbled along—at least the reviews were mixed, with some positive comments. And they kept tinkering with Act III every step of the way to the Boston tryout.

And in Boston, the play connected with the man who pretty much turned it into a major success, a reviewer named Elliot Norton. His review was titled, “Oh, For a Third Act.”

Elliot Norton also had a TV show in Boston and one night during “The Odd Couple” tryout he had Nichols, Carney, and Matthau as his guests. Simon was in a daze, still trying to figure out what to do to fix the script and barely heard Norton talking to him about the show—until he said, “You know what I really missed in the third act? I missed the Pigeon sisters” —those were two women who came over to Felix and Oscar’s place for a disastrous date. “They were so darned funny and I wondered why you didn’t bring them back.”

And that, according to Neil Simon, is what ultimately saved “The Odd Couple.” Writing at white-heat, he put the ladies back into the play during Act III and the next night, yet another new and improved Act III went up before the Boston audience.

And—they didn’t like it. Simon was ready to throw himself under a train, but Nichols had one, last suggestion. “Yes, the Pigeon sisters should re-appear in the third act,” he said, “it’s right that they should be there but they’re there for the wrong reason. You need to find a different, better reason to bring them back in Act III.”

So Simon spent another two days and nights at his typewriter. And the latest rewrite of Act III went up on stage.

And it worked, this time, it worked. The audience lit up. They enjoyed it, the story line made sense, and it was solidly constructed. This time, the Pigeon sisters come into Act III to get Felix Ungar’s belongings. After Oscar throws Felix out, he pours his heart out to the two ladies—and finds himself a new place to live. For awhile, anyway. With the very sympathetic and attractive Pigeon sisters.

It just felt right to the audience. Both the story and the characters were now believable, it made sense, and people could empathize with everything they did.

“The Odd Couple” was an enormous success; it won four Tony Awards and practically made Neil Simon a household name. He went on to write plenty of other hits for stage and screen—but he did make one huge mistake as far as “The Odd Couple” goes.

When he was negotiating with Paramount Pictures for movie rights to his hit plays, Simon apparently missed some of the fine print. Paramount paid him $125,000 for “The Odd Couple” and “Barefoot in the Park.” And, as he says in one of his books, he never received a dime from “The Odd Couple” TV series—which ran five years and went into syndication and DVD distribution; on top of that, he gave up all stage rights to “Barefoot in the Park.” Simon figures he lost several million dollars altogether.

When it came to writing contracts—Neil Simon was one hell of a playwright.

A comedy writer might become famous and make a lot of money, but what he won’t get are things like reverence, deference, and adulation.

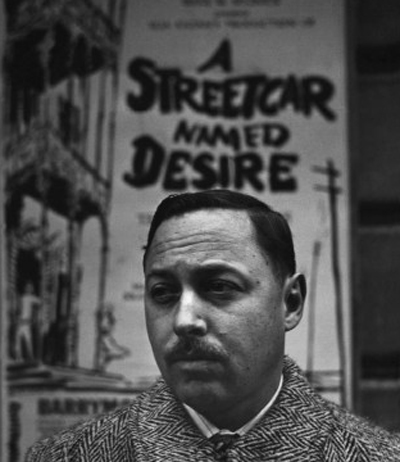

That sort of thing is usually reserved for serious writers who write serious work. Like Tennessee Williams and “A Streetcar Named Desire,” which won the 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. No surprise that Williams made it to postage-stamp immortality and Neil Simon didn’t—at least not in his own country, as far as I know. There is a Neil Simon postage stamp, but it’s from the Lesser Antilles. Now THAT’S funny.

“A Streetcar Named Desire” wasn’t called that to begin with. Before Williams finally settled on a title, he tried “The Passion of a Moth,” “The Primary Colors,” “Electric Avenue,” “Blanche’s Chair in the Moon,” and “The Poker Night.”

Williams actually started writing “Streetcar” before “The Glass Menagerie” opened on Broadway in 1945. And he said that “Streetcar,” like “The Glass Menagerie,” was inspired by his fragile, doomed sister Rose. A lot of it was written in 1946 in New Orleans and Key West. In 1947, he abandoned it as “hopeless,” then picked it up again and finally finished the play, pretty much, by the spring of 1947. The various drafts would ultimately add up to almost 800 manuscript pages.

His work habits were described by Elia Kazan, the man who would later direct “Streetcar” on stage and screen:

Every morning, he’d get up, silent and remote from whoever happened to be with him, dress in a bathrobe, mix himself a double dry martini, put a cigarette in his holder, sit before his typewriter, grind in a blank sheet of paper, and so become Tennessee Williams.

Williams’ own description of his morning routine was a little different: “I would rise early,” he said, “have my black coffee and go straight to work.” In any event, the rising early was quite an achievement in itself since the Williams residences were known for heavy drinking and late-night parties.

The person who “happened to be with him” at the time was Amado “Pancho” Rodriguez y Gonzalez, a man with an unfortunate tendency toward violence. But it might be a little unfair to put all the blame on Pancho. Fritz Bultman, an artist who knew Williams well and occasionally roomed with him, said the playwright deliberately provoked Pancho, then used his outbursts as raw character material—and even some of the dialogue—for Stanley Kowalski.

It’s certainly possible; Williams never claimed to be a saint. In his memoirs he wrote, “To know me is not to love me.” Bultman also said that around this time, he started noticing “…something opportunistic and abusive in Tennessee … something seemed to go sour in him…”

In 1947, the play about Stanley, Stella, and Blanche was finished and sent off to Williams’ agent, Audrey Wood. Wood had an agency business with her husband, William Liebling; Liebling handled actors and directors, Wood handled writers.

The play was still called “The Poker Night” at this point, but Wood didn’t like the title one bit; “It sounds like a Western,” she said. Williams finally took her advice and changed the title yet again—to “A Streetcar Called Desire,” and at last to “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

With script in hand, Audrey Wood started leaving messages for a woman named Irene Mayer Selznick about producing “Streetcar.”

If you could learn producing by osmosis, Irene Mayer Selznick would have been the world’s greatest producer; she was the daughter of one legendary Hollywood producer—Louis B. Mayer—and the wife of another—David O. Selznick.

But at that particular moment, she was the estranged wife of David O. Selznick. After the big Hollywood wedding, life with Selznick turned out to be no day at the beach. He gambled heavily, cheated on Irene every chance he got, and was hooked on Benzedrine (a habit he picked up while producing “Gone With the Wind.”)

Selznick’s messy, public affair with movie actress Jennifer Jones was the last straw for Irene Mayer Selznick; they separated in 1945 and would divorce in 1948. As her marriage fell apart, Irene spent more and more time in New York, distracting herself by dabbling in the theatre. Her track record as a stage producer—or any kind of producer, for that matter—was practically nonexistent. Her best-known project was a minor disaster called “Heartsong” —and that was about it.

Audrey Wood (Williams’ agent) just happened to be married to the casting director on “Heartsong,” her agency partner, William Liebling. So that’s how Audrey Wood knew Irene—but why would she offer such an inexperienced producer such an important project?

OK, Irene was very sharp and she knew a lot about show business.

But there was more to it than that—because Audrey Wood was every bit as sharp and also knew a whole lot more about show business than Irene Mayer Selznick.

Irene, even with that one, single, crummy production under her belt was the answer to an agent’s prayer. Irene’s connections weren’t just gold-plated—they were solid, 24-carat gold. She could probably persuade any number of wealthy relatives and friends to invest in the new Tennessee Williams play. Friends like Cary Grant and John Hay Whitney, to name just two.

And—she was worth around 16 million dollars.

In 1947.

But Irene ignored Wood’s phone calls and messages, still smarting over the failure of “Heartsong.” Wood finally strong-armed Irene into a meeting. “My most cherished and important client has a play I would like to put in your hands,” Wood said, and told her all about the new property.

Irene was hesitant—Tennessee Williams was a name playwright; he had written “The Glass Menagerie,” winner of the 1945 New York Drama Critics Circle Award. And after she read “Streetcar,” she was even more hesitant; “It’s beyond me,” she told Wood. Forget it. After all, her track record as a producer could be summed up in one word: Flop. It was as if she’d crashed a Cessna during pilot training and was suddenly being offered a Sabrejet.

But Wood was very persistent. She flattered, she cajoled, she wouldn’t take no for an answer. Basically, the same tactics perfected by Irene’s legendary father, Louis B. Mayer.

Irene suggested they meet with Tennessee Williams and let him decide whether or not she was fit to produce his new show.

And so they did.

Why, of course, Williams thought Irene would be the perfect producer! In fact, he’d be delighted to have her produce his next play! And the contracts just happened to be all prepared and ready to sign. Everyone put their name on the dotted line and Williams started calling his new producer “Dame Selznick” and “Madame Selznick.” Years later, oddly enough, he remembered her as being pretty eager to produce his play. In fact, Irene even put about $25,000 of her own money into the show—a windfall even Audrey Wood hadn’t counted on.

And she did get Cary Grant and John Hay Whitney to invest.

The reaction on Broadway to Irene Mayer Selznick being named producer of the new Tennessee Williams play wasn’t what anyone would call positive. You might even describe it as a sort of stunned outrage—Irene Selznick?!? That tinsel town brat, that rank amateur, that—professional divorcée?? Her?

But Irene wasn’t about to take any crap from New Yorkers—she was, after all, the daughter of an emperor.

The next order of business was lining up a director. Tennessee Williams had recently seen Arthur Miller’s play “All My Sons,” which was directed by Elia Kazan and he decided that’s the guy for us. Williams wrote Kazan a letter praising his skills and Irene sent him the script. He said no. Kazan was one of the New Yorkers who had sneered at the very idea of Irene Selznick producing anything. And he was also ticked off that he wasn’t the only director Irene was talking to. That kind of thing might be standard practice out in the hinterlands of Hollywood, but as far as Kazan was concerned, that’s not how we do things in the legitimate theatre.

Then, Kazan’s wife Molly started badgering him to do it. She knew it was too good to pass up. There was a lot of backing and forthing, off and on negotiating. Kazan was a forceful—a very forceful—personality. At one point, he actually got worried that he overdid it; he sent Williams a telegram saying, “I don’t think Irene should be quite so frightened. Let her talk to some of my references. There are an awful lot of people I’ve worked with who I didn’t terrify.”

Williams urged Kazan to show some “warmth and deference” to Irene. Nothing could have annoyed him more but finally, he agreed to direct the play—under certain conditions. First, Kazan wanted Irene thrown off the project. Williams flatly refused. He knew what side his bread was buttered on. Kazan said he also wanted “absolute artistic powers over all production decisions and a billing that would ensure those rights.” And, of course, there was the issue of money. The lawyers did their thing and eventually hashed out an agreement:

Irene would definitely remain as producer but Kazan would have complete creative control – along with 20% of the profits. The negotiations over money were almost dwarfed by the bickering over credits—remember, we’re talking show business here! The final wording read something like a royal marriage contract from the Middle Ages: “Irene M. Selznick presents * Elia Kazan’s Production of * ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ * by Tennessee Williams * Directed by Mr. Kazan with * – “ and the names of cast would fill in the rest of the blanks.

Which brought up the next question—who was going to be in this thing?

Kazan, Irene, and Williams all thought Bette Davis would be wonderful as Blanche—but she was unavailable. Irene had Margaret Sullavan read for Tennessee Williams and Williams said, “She sounds like she should be holding a tennis racquet.” Exit Margaret Sullavan. They were starting to get a little desperate—Kazan even suggested Mary Martin, which just made Williams laugh.

Word quickly reached the west coast about the casting search for the new Williams play and it was music to the ears of Hume Cronyn, an established stage and screen actor living in California, married to an English actress named Jessica Tandy.

Cronyn had helped support Tennessee Williams through the lean years by optioning one-acts from him at 50 dollars a month. He thought his wife would be great as Blanche DuBois—so it was time to call in a favor.

Cronyn let Williams know that he would like him—and Kazan and Irene—to come out to Los Angeles and see Jessica Tandy perform one of the short plays he’d optioned from Williams years ago— “Portrait of a Madonna.” Now, this particular one-act was like a preliminary sketch for “Streetcar.” It was about a half-demented woman living in a romantic fantasy who ends up being carted off to an asylum. A more perfect audition for Blanche DuBois there could never be.

And they did come out and see it—and they agreed with Cronyn—Jessica Tandy would be great as Blanche DuBois; they signed her up.

And Stanley Kowalski? Well, casting that part would be easy. Everybody was sure it was going to be John Garfield.

It was important to have a name actor and Garfield fit the bill perfectly. He was a movie star, but he came from the New York theatre and always wanted to return. Before he left for Hollywood, he’d worked with Kazan and they liked each other. He was also known for playing tough, working-class guys. On top of all that, Garfield loved the script and wanted the part. No problem—right?

Well-l-l-l, Garfield had a few conditions that had to be met before he’d sign up. OK, like what? He wanted the right to leave the show after four months—after all, you never know when a movie contract might come along. He also wanted a guarantee that he would play Stanley Kowalski in any film version; and, he wanted Williams to do a rewrite. A rewrite? Garfield wanted more lines for Stanley, so he would be seen and heard at least as much as Blanche. Really? Gosh, John, what else would you like? Well, now that you ask—Garfield wanted a number of cues to be reworked so the curtain would fall at moments that would maximize the dramatic impact of the Stanley Kowalski character.

As much as they wanted to have John Garfield as their Stanley, enough was enough. Garfield was o-u-t, out. Negotiations with Burt Lancaster (Irene’s second choice) also fell apart. Van Heflin, Edmund O’Brien, even Gregory Peck were considered. No go.

It was now a month before rehearsals started—and still no Stanley Kowalski.

There are conflicting versions about what happened next, but from everything I’ve read, here’s how they found their Stanley—and how Marlon Brando became a star:

It seems that Brando’s agent had been bugging Kazan to consider young Marlon for the role of Stanley.

Around the same time, Tallulah Bankhead also suggested Brando for the role; Bankhead had just worked with him in a play and hated him—she also thought he’d be perfect as Stanley. “My Dear Mr. Williams,” she wrote, “I must turn down the role of Blanche DuBois … but I do have one suggestion for the casting. I know of an actor who can appear as this brutish Stanley Kowalski character. I mean, a total pig of a man without sensitivity or grace of any kind. Marlon Brando would be perfect as Stanley. I have just fired the cad from my play and I know for a fact that he is looking for work.”

Brando said the disgust was mutual; he found Bankhead every bit as revolting and, in fact, claimed that it was his decision to quit her play.

At that time, Brando had almost no track record as an actor, and certainly not as a male lead. He’d made a good impression in a few—very few—Broadway appearances. And Kazan considered him not only too young but “too pretty” for the part.

Even so, Brando’s agent sent Brando a copy of the script; he read it and decided that the part of Stanley Kowalski was “…a size too large,” as he put it. He tried calling Kazan to turn it down but the line was busy. “If I’d gotten through to him,” Brando said years later, “I’m certain I never would have played Stanley Kowalski.” He decided to sleep on it.

Not that he did much sleeping. Brando, even then, was a notorious eccentric. He seldom had any fixed address. And when he did, he usually lived in a cruddy apartment with a filthy pet raccoon and a highly unlikely roommate—actor Wally Cox. Yep, that’s right. Mr. Peepers and the voice of Underdog.

“He was like a child,” Kazan remembered, “but there was so much violence in him … he never knew where the hell he was going to sleep, you didn’t know who he was angry with, or what he was angry about.”

The next day, Kazan called up Brando and asked him if he was interested or not. Brando swallowed hard and said yes.

Kazan then arranged a brief meeting with Irene, who was more than willing to go along with any decision Kazan made—as long as he made it soon.

The next step was to have Brando read for Tennessee Williams. But Williams was vacationing with Pancho and friends in Provincetown, way out at the tip of Cape Cod. Fine, Kazan gave Brando twenty dollars and Williams’ beach address and told him to take the bus to Provincetown. Brando headed off and Kazan phoned Williams and said to expect a promising young man at his door to read for Stanley. After three days, Kazan called Williams to find out what he thought about the actor. Williams said, “What actor?”

Brando had instantly spent the twenty bucks on food, picked up a girl, and was leisurely hitchhiking his way out to Provincetown.

He finally showed up one night and knocked on Williams’ door. It was dark inside. “What happened to the lights?” Brando asked. Well, the electricity went out a few days before and, what with all the relaxing and partying, nobody had gotten around to fixing it. “There was considerable consumption of fire-water,” Williams said. Also, at one point, Pancho tried to run over Williams with his car and the playwright ended up hiding under a pier for most of the night.

Brando put pennies in the fuse-box and, voila, the lights came back on. Which is when he noticed something else – the one and only toilet was plugged up and overflowing. Where did people go to—uh—relieve themselves, he asked? Well, they went outside and used the bushes. Nobody had gotten around to fixing the plumbing, either. Brando cleared the toilet (with his bare hand, by some reports), and then read for the part of Stanley Kowalski.

After about thirty seconds, Williams was sold—he called Kazan and Irene and told them Brando was a “God-sent Stanley.” He gave him some money and sent him back to New York, where the contract-signing ritual was performed. There were no problems like they’d had with Garfield or Lancaster; Brando committed to two full years.

The supporting roles were quickly cast. Irene knew Kim Hunter from Hollywood—she would play Stella; Kazan knew Karl Malden from the New York theatre—he would be Mitch, Stanley’s best friend.

Rehearsals were held in the roof annex of the New Amsterdam Theatre—an appropriately spooky, dilapidated place that was way past its prime—a lot like Blanche DuBois.

It wasn’t even a live theatre any more—the Great Depression had seen to that. In 1937, it was converted into a second-run movie house. But at the very top of the building, 12 stories up, there was still a theatre space available for rent. It was called The Roof Garden and had originally been used by Florenz Ziegfeld to stage his infamous “Midnight Frolics,” where showgirls would perform on a glass walkway—so the audience could look up their skirts. The place was extensively remodeled in the 1990s and became the headquarters of Disney Theatricals—complete with glass walkway, but more respectable. Back in 1947, the Roof Garden Theatre was the perfect place to bring “Streetcar” to life: Seedy and disreputable.

The relationship between producer and director never really improved; after all, Kazan thought the very idea of Irene as a producer was just laughable. On top of that, she came from the Hollywood tradition where the producer was in charge. Kazan, on the other hand, came from the New York theatre, where the director called the shots.

During the first few rehearsals, Irene sat behind Kazan so she could lean forward and offer suggestions and criticism—which she did pretty often. Finally, Kazan had enough. He turned around and yelled, “For crissake, Irene, get outta my ear!” and banned her from sitting anywhere near him.

Williams would approach Kazan deferentially and was treated more kindly. He usually sat way in the back during rehearsals and when he had a suggestion, he’d either bring it up quietly or jot it down and just tuck it into the director’s coat pocket. But at one point, he abandoned the subtle approach. It was Jessica Tandy’s charm that finally got to Williams. Blanche DuBois wasn’t intended to come across as naturally graceful or authentically enchanting—her charm, grace, and refinement are supposed to be transparently phony. A desperate, drowning woman trying to come across as something she’s not, hoping to find safe harbor at last. But charm and grace were genuine qualities that Jessica Tandy had in abundance—and that was a problem, as far as Williams was concerned.

“To my own astonishment,” Williams later recalled, “a loud and stricken voice rose from me. ‘What is she doing?! I didn’t write this part for an ingénue!’” Tandy dissolved in tears and disappeared into the far gloom of the rehearsal space, followed by Kazan. After fifteen minutes of “silken whispers” from the director, she went back to work. And Kazan took Williams aside and said, “Tennessee, never talk to an actress.”

Despite all the tension between Irene Selznick and Kazan, she still managed to do some very useful things in her capacity as a Hollywood-style producer.

Brando was dedicated to building muscles for this production—he wanted Stanley to look like a hulking bully. He lifted weights every chance he got and did things like sparring and wrestling with the other actors. One day, in the middle of an Indian-wrestling match between Brando and another actor, Irene’s voice rang out loud and clear. “Boys!” she shouted. That’s when they both tumbled into the orchestra pit; fortunately, they weren’t injured but Irene had seen enough. “You will not do that kind of thing again, period,” she said in a level tone. “You are both valuable pieces of property and this is no time to endanger the prospects of this production.” Louis B. Mayer couldn’t have said it better.

She also urged Williams to keep what turned out to be the best-known line in the entire play— “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.” Williams was thinking about changing it or cutting it out entirely but at Irene’s insistence, it stayed in as originally written.

In addition to all that, she also managed to have Pancho hustled out of town after he went into a rage and busted up Williams’ hotel room. Cleaning up messes—artistic and personal—was a traditional part of the Hollywood producer function. She was indeed her father’s daughter.

Brando was often pure misery to work with—shaky on his lines, playing stupid practical jokes, doing dumb things that he thought “sparked spontaneity” but just threw everybody off their timing. Jessica Tandy said he was “an impossible, psychopathic bastard.” But they were all willing—just barely—to put up with him because he was so good as Stanley.

When the time finally came for tryouts in New Haven and Boston, Kazan thought he’d done just about everything a director could do.

Now it was up to the audience.

The show was a technical mess at the tryout in New Haven—the lighting cues were relentless and confusing and there just wasn’t enough time to work them out before the curtain went up. Over 60 light cues, not to mention incredibly complicated music cues. Not unusual these days, but this was 1947.

The after-show party was downbeat and Irene remembered there was “none of the real excitement I had expected…” The word “artistic” was being thrown around far too much, she thought—that could be the kiss of death.

But there was one man at the party who was beaming. He had no doubts whatsoever about the show—Irene’s old man, Louis B. Mayer. Mayer was in the audience at the New Haven tryout—and L.B. couldn’t have been happier. Mayer ushered his daughter into another room, past the shrugging shoulders and the polite smiles and the “I-feel-for-you” nods.

Mayer sat her down and said, “Irene, these people are a bunch of goddamn fools. You don’t have a hit, you’ve got a smash. You wait and see.” Of course, Mayer would have preferred that the play have a happy ending and he said as much to Kazan. Kazan was unmoved, to say the least. But if there was one thing Louis B. Mayer liked even more than a happy ending, it was a good cry. And “Streetcar,” in addition to everything else it was, could certainly be that. If Mayer knew nothing else, he knew audiences; they had been his lifeblood for 40 years.

When the show opened on Broadway at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre the reception, both critical and popular, was overwhelming. It ran for 855 performances, won the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award, the Pulitzer Prize for Drama, and Jessica Tandy won a Tony. It became one of the most-frequently performed plays all over the world, a classic, and a perennial favorite—and in 1999, it even got its very own postage stamp.

Just like Tennessee Williams. And Neil Simon.

Table of Contents

David Wiener has written cover, feature, and interview articles for various performing arts magazines including American Cinematographer, Producers Guild Journal, Cahiers du Cinema, and The Journal of the Royal Photographic Society of Great Britain. His plays have been produced in London, India, Canada, Australia, Mexico, and the U.S. and have been published three times in the Smith & Kraus “Best Plays” one-act anthology series. He In 2007, he completed a Literary Internship with La Jolla Playhouse and went on to work as that theatre’s Dramaturgy Associate during the 07-08 season.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

One Response

This is a great story. Well done. Theater is a crazy business and I’m glad I’m out of it.