Harlem Afternoon

by Jessica Levine (December 2020)

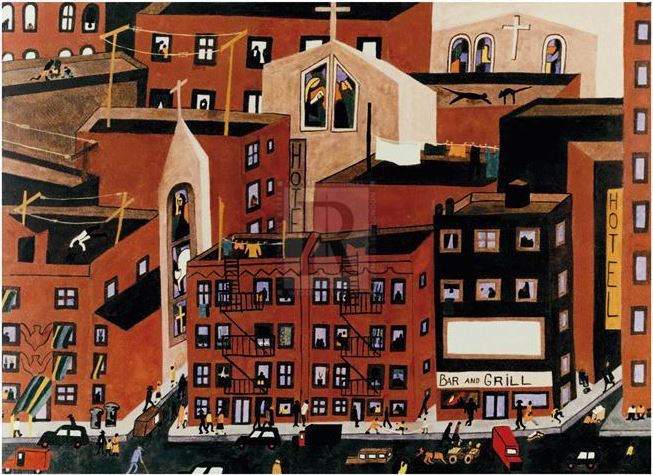

Harlem, Jacob Lawrence, 1942

Julia was a college senior and in the throes of her first romantic relationship when winter break rolled around and she was separated from her new boyfriend, Ben, who got on a plane to visit his parents in London while she went home to Manhattan to spend the holiday with hers.

Julia had met Ben when he was the graduate student instructor in her last English class. He was older than she and had a complicated past that included an old girlfriend in Paris whom he’d be seeing over the break. Ben had met Dominique years before when he’d gone to Paris to study French. In an unguarded moment he had described her as “a free spirit and a real revolutionary,” so now Julia tortured herself with visions of this mysterious Parisienne she imagined with silky hair and big, silver earrings, miniskirts, and Italian sandals. Julia consequently spent the first days of winter break snacking on chocolate, picking at her cuticles, and making pathetic entries in her journal. Fortunately, Ben’s apartment mate, Michael, whose parents also lived in Manhattan, called and suggested they get together.

“Come get me at my parents’. You can meet my brother, and we’ll go for a drink,” he said.

Michael’s father taught at Columbia University, which entitled him to one of its coveted pre-war faculty apartments on West End Avenue between 116th and 117th Streets. Julia took the elevator up to the sixth floor and rang the bell.

Michael swung the door open. “Hello!”

There was an awkward moment. Should they hug, kiss, or just nod? They nodded and Julia stepped into the living room. A couple of beat-up couches, a shiny grand piano, built-in bookcases. She went to the window for the view of the Hudson and beyond. The river had white peaks from the winter wind, and patches of snow glinted on both sides of the river, brightening the urban landscape.

“Nice apartment,” Julia said. “And nice piano.” Like Michael, she played but her artistic ambitions were more literary than musical.

Michael shrugged. “My dad’s.”

“That’s right. You mentioned he’s a musicologist.”

“A distinguished musicologist,” he sneered, then turned toward the kitchen. “Hey, Nick, come on out and meet someone.”

Michael’s brother came out, looked at Julia, nodded. He was much younger than Michael, probably college-aged.

“This is Ben’s girlfriend,” Michael said to him.

Julia grimaced. “That’s right, I’m ‘Ben’s girlfriend.’”

“Sorry . . . ” Michael flushed. “Nick, this is Julia.”

Nick stepped forward, stopped, leaned against the door jamb separating the dining alcove from the living room. “What are you guys up to today?”

“I thought I’d take her to the Peacock,” Michael said.

“And visit Gladys?” Nick asked.

“Who’s Gladys?” Julia asked.

“A very smart lady next door to the Peacock,” Michael said. “You want to come?” he asked his brother, surprising Julia, who thought it was going to be just the two of them.

“No,” Nick said.

Julia felt relieved.

“Okay.” Michael touched her arm. “Come on, let’s go.”

In the elevator Julia looked at him sideways. He had a large, sculptural head and a sensuous mouth, but he hadn’t shaved and the collar of the shirt sticking out from his leather jacket was stained. A complicated man and too old for me anyway, she thought. He was five years older than Ben, who was five years older than she was. The math wasn’t pretty, given that Michael was a graduate student.

“Where’s the Peacock?”

“One hundred twenty-fifth.”

“Harlem?” She was surprised. In the 1970s Harlem hadn’t yet been gentrified, and white people didn’t go there to hang out.

“You nervous?”

“Of course not,” she lied.

They fell silent, walked out and up the hill toward Broadway, then north. She felt a necessity to connect: she was sleeping with his apartment mate, and he was sleeping with her cousin, Robin. Conversation turned out not to be difficult in spite of their age difference. By the time they reached 120th, they were on a roll, talking about growing up in Manhattan and their favorite places and school, of course.

“What did you do between college and graduate school?” Julia asked.

“I was a working musician. I gave lessons and played gigs. Honestly, I’m not sure what I’m doing back in school.”

“Following in your father’s footsteps?”

“Sort of. Maybe not the smartest thing. I like giving private lessons, but an academic career like my dad has—I’m not sure I’m cut out for it. But once I started composing, it seemed like the logical thing to try . . . Now, this bar we’re going to, I’ve been hanging out there since college. Used to play with a jazz band there.”

“And who’s this Gladys?” she asked as they approached 123rd, the dividing line between the white and Black sections of town.

“A kind of lay minister and therapist. You’ll see. But first let’s have a drink to decide what we want to ask her.”

Julia had mainly seen Harlem from the Long Island Railroad on her way to visit family. The train passed over the eastern and poorest areas, and she had always reacted to the broken windows, the garbage-filled lots, and the graffiti with a mixture of compassion and horror. She thought of Harlem as a sad and dangerous place and so was surprised, when they reached Broadway and 125th, to find it bustling with commercial activity. It was Saturday and people were milling in and out of grocery stores and lunch spots. Shops spilled out onto the sidewalks with cheap wares in boxes on folding tables: sunglasses, scarves, hats. Drawn by the burgundy color of a beret, Julia stopped to look at it. The Black shopkeeper gave her a big smile. “Three dollars,” he said.

“Maybe on the way back,” she said, not being an impulsive buyer.

“Here’s the Peacock,” Michael said.

They went down five steps and stepped into a small, dimly lit bar. Julia and Michael were the only white people there. Two Black ladies in wide-rimmed Sunday hats, one a bright purple, the other bright red, sat at a little table by the wall. A couple of older guys were reading their respective newspapers at the far end of the bar. Two couples at a square table were having fancy-looking cocktails.

“Beer?” Michael asked. Julia nodded. He sat down at the bar, and she took the stool next to him.

“You come here a lot?” she asked him.

“Not so much anymore but I did when I was in high school and wanted a joint—or worse.”

“You did a lot of drugs?”

“Mostly dope but also some hard stuff. It was Gladys who helped me stop. At least the hard stuff. As you know, I still like my weed.”

“How did she get you to stop?”

“This is what happened. My kid brother started doing heroin at fifteen, and I was the first one to find out.” The corners of his mouth went down. “I realized it was largely my fault: I’d been setting him a bad example. My parents weren’t getting along at the time—in fact, they were talking about separation—so it was up to me to become my brother’s keeper because no one else was going to do it. It was Gladys who made me see that.” Michael pulled out a pack of cigarettes and lit one. “Maybe one day I’ll ask her to help me give up cigarettes and weed, too.”

“And Nick?”

“I moved into his bedroom. For a month I followed him everywhere.” He laughed. “I’d frisk him before he went into the bathroom and check the size of his pupils after school.”

The beer came. Julia drank some and began to relax. Nobody in the bar seemed to mind their white presence, so why should she be uptight about it?

“Are you still your brother’s keeper?”

“Yes, but now he’s mine too.”

“I see.”

“Now let’s get down to the business at hand, Jul. What are we going to ask Gladys?”

She registered the “Jul.” It was the first time he’d used a nickname for her, and she liked the intimacy it implied.

“I’m not sure.”

“You know that last time you came over before Ben left, I couldn’t help overhearing the two of you having a ‘discussion.’”

“Did you know he has a girlfriend or an ex-girlfriend in Paris?”

“Yeah, Dominique.”

“That ‘discussion’ happened when I found a picture of her in his wallet. I hadn’t known about her before.”

“You’re a snoop then?” He chuckled.

“Not usually but I felt something was up. He was being so quiet about his plans.” Tears came to her eyes. “There I was feeling so in love and romantic about him—my first boyfriend, finally, yay!—” (she rolled her eyes in self-derision) “—and there he was planning a reunion with his ex.”

“Maybe planning to see her but not necessarily a ‘reunion.’ Hey, Jul, you may be working yourself up over nothing.”

“What do you know about her?”

“Not much, really. But the fact that he’s still in touch with her suggests he’s a person capable of loyalty. That’s a positive, don’t you think?”

Julia sighed. “I guess.”

“In any case, whatever their tie is, it wasn’t strong enough to keep him in Europe. He chose to do graduate school here.”

“He could still go back. To London. Or Europe. And her.”

“So you want to ask Gladys something about Dominique? Like whether she’s a threat?”

“That sounds right.” Julia looked at him. “And what about you? What’s your question?”

“Your cousin . . . ” He shook his head. “Robin is one complicated gal. I could ask a dozen questions about her. To start with, why can’t she untangle herself from that woman in Boston she was involved with? Maybe she’s really gay, not bi.”

“I think that relationship was an experiment. A women’s college thing.”

He shook his head. “I’m not sure about that. I think she likes sex with men, but she doesn’t like men as a—as a ‘species.’ Like the act is fun, but men are, emotionally, not to her taste.”

“I don’t know.”

“I thought you guys were close?” he asked.

“Sort of but not really. She was always like a big sister to me, telling me what to do, but a little remote.”

“And there I was hoping for some inside information!” He grinned.

“And there I was thinking you just wanted to hang out and be friends!” She grinned back.

“Hey, Jul, of course. Of course, I want to be friends.”

The conversation went in another direction as they finished their beers. Michael put some dollars on the counter.

“Time to go see Gladys,” he said.

They got up and, in a gentlemanly gesture that surprised her coming from such an informal, messy guy, he cupped her elbow as they went up the stairs. He took a right and they walked down the street until he stopped in front of a pink neon sign that read Psychic.

She balked. “Michael! This is ridiculous!”

“Trust me, a Harlem treasure and a fount of wisdom.”

“I don’t know.”

“Jul!”

“Well, okay.”

They went down the stairs and he rang the bell. A portly Black woman in African robes and headdress opened the door. Her face lit up when she saw Michael. “Mike, baby doll! How ya doing? Home for Christmas? Tell me, tell me.” They exchanged a big hug.

“Gladys, you look like a million bucks. This is Julia, my best friend’s girl.”

“Now you watch your step with that one, boy,” she laughed.

“It’s not what you think,” he said, also laughing.

“I was kidding,” she said. “This is Gladys, remember. I know what’s going on. You both have love problems, you want advice, you’re hoping for a two-for-the-price-of-one Christmas special, ain’t you, boy?”

“You read my mind.”

“That’s my business alright.”

She sat down behind a little table that had several tarot decks on it. Julia and Michael sat down across from her. The floor was covered with a shaggy gold carpet; above a small bookcase hung photos of people both Black and white, some of them signed, and an impressionistic painting of the African savanna.

“You read cards?” Julia asked.

“The cards are to impress first-time customers. But with people who know and trust me, I don’t do that racket. All I need is a hand. Give me your hand, girl.”

Julia placed her slim, pale hand in Gladys’s large, dark palm. There was a dead silence for several moments.

“It’s strange. You’re twenty or twenty-one but you seem like you’re twenty-five, and your fella is twenty-five or so and seems like he’s a kid of twenty.”

Julia said nothing.

“I believe,” Gladys continued, her speech becoming more formal and oratorical as the inspiration mounted, “you have not studied his character sufficiently. And the reason you have not done this is that he is a difficult one to understand, his character not yet being formed. He is a serious man and will have success in what he does, but this may be as much of a burden as a boon to you. You must be careful. This man you may decide to marry one day will not be the same as the man you met. He may be a less exciting man, too involved in his work, not as interested in life as you think he is. And you—” She stopped and looked up from Julia’s hand into her eyes with kindness, “you are a poet who needs to be out and about in the world, collecting feelings and impressions. This man you love may stand in your way.”

Julia looked at Michael. “Did you tell her I write poetry? Did you tell her about Ben?”

Michael shook his head. “I haven’t seen her since last summer.”

Julia looked back at Gladys. “You don’t think he’s the man for me, then?”

“I don’t know ’cause I don’t know what he’s gonna turn into,” Glady said, her speech and manner returning to earth. “It could go either way. But be careful—he’s a fella who loves books more than anything. You could get awful tired of competing with those books.”

“Right now, it’s a woman in Paris I’m competing with, not books. I want to know whether I should worry about her.”

Gladys shrugged. “Another woman is nothing compared to a pile of books.”

Perplexed, Julia frowned.

“You gotta ride the river, honey. That’s all I can tell you now.”

“But you’re saying I don’t have to worry about the woman in Paris?”

“Nah, your fella’s done with her. Or will be by the time he gets back. He hit the jackpot with you, and he’s realizing it right now.”

Julia nodded.

Gladys’s gaze shifted to Michael. “Your turn, honey.” She put her hand out, and he placed his in hers, palm up.

“The lady you’re going with is a little wild. Wild isn’t what you need. Wild isn’t what you want. What you want is love. What you need is love. Don’t waste your time on it if it ain’t love.”

“I hear ya,” he said.

“And let me tell you why you shouldn’t waste your time. You shouldn’t waste your time because your heart gets broken either way, my friend, either way. Every time you take into your bed a lady who’s not the right lady, a little bit more gets chipped away from that heart of yours. Because you’re a man as deep as the ocean. Take my advice and find yourself a woman that deep, won’t you, Mike? Stop wasting your time.”

“I hear ya,” Michael repeated, looking drawn and gray.

He withdrew his hand but she took it back with one hand and, with her other, reached for Julia’s. “You two will be great friends, and you must support each other through what is to come.”

Gladys released their hands. Julia and Michael looked at each other. They stood up to go, and the older woman followed suit.

“Still twenty bucks?” Michael asked.

“Same price for you till the end of time.”

He placed a twenty-dollar bill on the table and they hugged.

Pulling back but still holding his arms, Gladys gave him a hard look. “You still clean, Mike?”

“As a whistle. Except for weed.”

“You watch out for Mary Jane. Both a saint and a whore, that plant.” She let go of him. “Tell your little brother to stop by.”

“Will do.”

“You come again soon,” Gladys said. She walked them to the door, where she stopped, put her hands on Julia’s arms, and closed her eyes. “God bless you.” Then she turned to Michael and did the same.

Julia and Michael went up the half-flight of stairs back to the street. The work day was over, and the streets were crowded with people going home.

“Did you feel that? A blessing from Gladys is a powerful thing,” Michael said.

“Yeah,” Julia said, “but Jesus, I thought people paid fortune-tellers to say nice things to them. That was really depressing.”

“It was, wasn’t it? But she speaks the truth every time. I’ve known her for fifteen years, and she’s always right on target.”

“Jesus,” Julia repeated.

“Need another beer?”

“You bet I do,” she said.

“Here,” he said. “Take my arm.”

She passed her arm through his, and they headed, both a little dazed, back to the Peacock.

__________________________________

Jessica Levine is the author of two novels, Nothing Forgotten, a Next Generation Indie Award winner in the Second Novel category and a finalist in General Fiction, and The Geometry of Love, a Top 10 Women’s Fiction Title in Booklist. The novels are part of a “Cousins Trilogy” that will include a third novel, provisionally titled Shambles and Light. She has also published a literary history, Delicate Pursuit: Discretion in Henry James and Edith Wharton, and her essays, short stories, and poetry have appeared in many publications, including The Southern Review and The Huffington Post.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast