He Was Not Like Robin Hood

by Geoffrey Clarfield (April 2023)

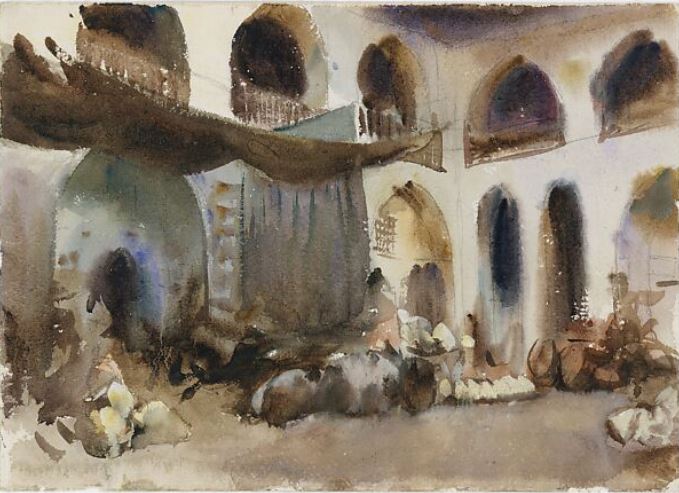

Market Place, John Singer Sargent, 1890s

The old city or the “medina” of Tangier has a Synagogue Street. These synagogues were full and active community centres until shortly after Moroccan independence in 1956, when Morocco joined the Arab League and endorsed the Nasserist desire to destroy Israel.

The Nahon Synagogue is the gem of the many Jewish houses of worship that used to be centres of community life in pre-independence Tangier. Writer Michael Toler described the Synagogue in 2017:

Located on a dead end street off the rue des Synagogues in the Beni Idir quarter of the Tangier medina, this synagogue was constructed in the 19th century by Moïse Nahon, a prominent educator and scholar from an influential Jewish family in Tangier. The synagogue ceased activity in the second half to the 20th century, and subsequently fell into disrepair until its restoration in 1994.It now functions as a museum.

The prayer room of the synagogue is accessible via a small courtyard at the end of the entrance corridor. The interior is elaborately decorated in an Andalusian style. Carved stucco walls are decorated with a repeating motif featuring ornamental embedded columns, trilobe arches, and arabesques with floral and geometric motifs. Perhaps most remarkable is the Arabic calligraphy repeated in three medallions vertically aligned below the superior lobe. Under this elaborate decoration, the lower portion of the wall is lined with rectangular, carved wood panels. The center of the prayer hall opens to a ceiling that is also elaborately decorated, with a large skylight in the center. The wooden ark and panels above it are decorated with Hebrew calligraphy. The carved wood lectern is on the southern side of the prayer area.

Wooden benches in the prayer area still bear brass plaques with family names. Ornate lamps are suspended throughout the synagogue and candelabras are placed on the wooden structures. The semi-circular windows above the entry portal and windows on each side feature a floral pattern in stained glass.

A stairway off the courtyard leads to an upstairs gallery that served as the hazara, or women’s prayer area. There is no carved wood or stucco decoration on the walls of the second floor gallery. Instead, it is decorated with framed embroidery, tapestries, banners, and other artifacts donated by the Jewish community in Tangier.

That is not entirely true.

When I arrived in Tangier to take up my job as Israeli Cultural Attache to the Kingdom of Morocco, I asked my colleague (and later my friend) Hamid, if I and nine male Jews (in Judaism you need ten males to make a minyan, the minimal number of people necessary for a complete religious service) could conduct Friday evening prayers at the Nahon.

He got us permission and so every Friday afternoon one of Hamid’s security men, dressed in modest European clothes with a somewhat pretentious trench coat that makes him look like an Arab version of Humphrey Bogart, knocks on my door and escorts me by foot to the synagogue where we carry on a tradition that has survived almost unbroken from the time of the final expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492.

Before taking up my posting, I had visited the mausoleum of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in Spain and marveled at the gold and silver used to adorn this national/religious site. I wondered how much of it was taken from the Jews of Spain who found refuge in Morocco, or from those who died on the way here. It bothered me. I took it personally. The place gave me a bad vibe.

I told my story to the Chief Rabbi of Morocco in Casablanca and he recommended that I pray for the souls of those who did not make it and died during the expulsion. And so I now pray for their souls every Friday evening with my Jewish coreligionists. If it does not help them, then at least it makes me feel better.

After the service we walk to the house of a Jewish resident of the old city and enjoy a sumptuous dinner enjoying the special tajjins (stews) and bread of Tangier. The Israeli Embassy in Rabat sends us ample amounts of Kosher wine to substitute for the wine and spirits whose production was once the monopoly of Moroccan Jews as the Muslim religion forbids the drinking of alcohol. (That did not stop Moroccan Moslem elites during the 19th century from buying wine from Jewish vintners when they wanted to have a good debauch. It was actually quite a common practice).

The Sephardic Jews, like those in Tangier, have always been a minority among the Jews of Morocco and North Africa. They came before and largely after 1492, when Ferdinand and Isabella expelled the Jews of Spain and threatened those that remained with forced conversion or death by burning at the stake.

Tens of thousands left and the majority landed in Morocco and North Africa where the Sultans and rulers of the day allowed them to remain as second class citizens under Islamic law. The Spanish King and Queen had forbidden them to take any of their gold and silver with them and so they arrived with only the clothes on their backs.

Although over the centuries, there was a fair amount of intermarriage and communal cooperation between these new immigrants and the ancient Jewish community that came to Morocco during and before the time of the Romans, their sophistication and worldliness always gave the Sephardim, as they are called in Hebrew, an advantage over their Moroccan Jewish counterparts as they never stopped speaking Spanish and used their commercial contacts in Holland and Britain to enhance their trading networks and political contacts. They were worldly whereas the other Moroccan Jews were insular.

For example, their Sephardic counterpart, the great British Scion of Zion, Sir Moses Montefiore, visited Morocco in the 19th century to try and persuade the Sultan to change the laws and customs of dhimmitude (the second class status given to Jews living under Islamic law) and which so degraded and circumscribed the lives of most Jews of Morocco.

From 1956 on, Tangier was no longer to be ruled by an international consortium of European powers and it soon came under a reconstituted national authority. This triggered a migration of Sephardic Jews from Tangier to France, French speaking Canada and Israel. There are only a few hundred left now from a recent count of about 8,000 people in 1956. Mr. Ozziel is one of those Sephardic Jews who have “stayed on.”

He is in his eighties and bears a remarkable resemblance to the Cuban music star Tito Puente of world fame. And, he has that lightness of being that so many healthy and agile men of the Mediterranean seem to inherit in their genes or, perhaps it derives from the olive oil based Mediterranean diet of their childhood.

Ozziel carries a cane. He does not need it to walk, but he tells me it helps keep the stray dogs away from him and just in case a local pick pocket thinks he just may be a tourist, he knows what to do if approached with hostile intent. He is also a gifted raconteur and one night he decided to regale us with the story of Raiusuni. His is a remarkable tale and all of it is true.

As he sipped on his glass of kosher wine he began,

“The palace of Asilah is a beautiful white Moorish castle not far from here and built right beside the sea. From its balconies and walkways you can see the stony beaches forty feet below you. It is a wonderful place to have an event. It was built by a rebel, bandit, politician named Raisuni.

“This is the kind of guy he was. When in the thick of one of his many battles and firefights he noticed it was time for the afternoon prayer. So, he summoned his servant who helped him off his horse and handed him his prayer rug. As Raisuni prayed his servant was shot and killed. Indifferent to his servant’s untimely demise he finished his prayers, summoned another servant who helped him onto his horse, and who was then shot in the leg a moment after. Then Raisuni rallied his men, threw himself into the thick of battle and ended the afternoon victorious.”

He went on,

“First off there is and has been a lot written about Raisuni. He even dictated his memoirs to an English journalist Rosita Forbes in 1923, two years before his death. She was a bit of Romantic and saw him as a legitimate social bandit fighting for the rights of his marginalized Berber speaking kin in the mountains of the Rif just north and east of here. But he was a much more complex figure and in many ways a typical Moroccan tribal leader, loyal for a time and then suddenly, traitorous, like the Berber General Oufkir who almost pulled off a coup d’etat against King Hassan II, the present king’s late father.

“I got many of my stories about Raiusuni from the ‘Jewish girls’ and from Jews in Tetuan. These were young women who worked in the growing number of mansions built in Tangier before and after WWI, populated with wealthy American women who had married impoverished British and European aristocrats.

“The women liked these girls. They learnt English, spoke Spanish, bargained with Arab and Berber merchants for quality merchandise and food at good prices and above all they did not want to sleep with the man of the house as they took these jobs to build a dowry and marry someone from their own that is to say, our community. One of these men was an American millionaire named Pedicaris.

“The first thing that any foreigner or visitor to Morocco must understand is that the country has always been divided into three areas. The first is the coastal area, conquered and settled by Arabs who founded the cities of Fez, Meknes, Rabat and repopulated Tangier which was a Roman town. This is called the land of the government, of the Sultan in Arabic the bled al makhzan. Then there is the chaos of the Sahara and the nomads there.

“The bled es sibah is that tribal area, highland and largely Berber speaking and who form a congerie of tribes who are dissident. The whole history of Morocco is one big pendulum which has swung back and for the between these two poles and Morocco has only been unified since 1956.

“Do not underestimate the Berbers, for if pushed too far they always revolt. And so just north and east of here are the Riff Mountains, Berber county. They are now almost exclusively the source of our wonderful Moroccan olives and unfortunately most of the hashish and marijuana that is smuggled into Europe by the Moroccan cartels, especially in the Rif. So imagine if Raisuni were alive today you know what kind of work he would be doing!

“By about 1903, the Sultan and the makhzan were at their weakest and bounced about like a ping pong ball amongst the French, Spanish, British and Germans, all vying for some potential imperial hegemony that they could exert here. Tangier was not the safest place at that time as you shall see as this story unfolds. And it goes without saying, that the Sultan did not control the Berber tribes of the Rif.

“Raisuni’s full name was Sherif Moulai Ahmed Ben Mohammed el Raisuni. He was a bilingual Arabic and Berber speaker. He claimed that he was descended not only from the Prophet Mohammed (thus his title of Sherif) but also from Morocco’s founding conqueror, saint and Sultan, Moulay Idris who founded the first Arab dynasty in the country in the 8th century.

“His shrine in Fez still draws visitors from all over Morocco who pray at his tomb and call on his baraka or blessing power to cure their ills or grant their wishes. And Raisuni was well educated for his time. He was literate and had been trained in Islamic law. But somehow the peaceful life of a Moroccan “saint” and scribe did not appeal to him.

“His own family had their own mausoleum in a mosque in Tetuan, a city in the Riff and local people would come there on pilgrimage. Today we would say he was born with a heap of ‘social capital.’ But in his case, the Moroccan values of honour and shame were too strong in him. He was cham moach (A Hebrew phrase meaning hot headed).

“Once upon a time, as we like to say, young Raisuni was minding his own business sipping tea in front of his house and admiring the view of the olive groves. Seemingly out of nowhere a young woman, in tattered clothes and bleeding profusely collapsed in front of him.

When he asked the fair damsel what had happened she replied, ‘My husband and I had been married for only a few weeks. We were on our way to Wazzan to pray at the tomb of the saints, to ask for healthy children. Ours was a love marriage and we were very happy. On the way we were attacked and robbed. They beheaded my husband and left me for dead after raping me.’

“It is said that Raisuni took her inside his house and asked the women folk to care for the bereaved widow. He then armed himself, got on his horse and found the bandits who had been so well described by the woman. They were sitting under a tree, laughing and showing each other the jewelry they had stolen from the women and the gold they had taken from the man.

“Raisuni explained that he too was a bandit and asked for more details. When he was absolutely sure these were the culprits he took out his two pistols and shot two of the men through the head and then strangled the third. He burned their bodies to insure that their souls would never go to heaven. He returned home and returned the valuables to the recovering bride. Raisuni had discovered his calling.

“The Sultan’s men and their soldiers were constantly defeated by Raiusuni when they tried to enter the Rif. But one day, thinking that as a brigand warrior he had won the respect of the Sultan, the Sultans advisors invited Raiusuni to Tangier promising to present him with a modern rifle and instead, even after having eaten together (which according to custom should have protected him from harm) seized him, tied him up and sent him off to prison.

“The Sultan sent him to the Atlantic city of Mogador where he was put in the dungeon. He spent years there but survived. At one point he spent three days chained to a dead man as his jailers were slow to take the victim out to be buried. Raiusuni’s living conditions there make those of the Count of Monte Christo’s prison resemble a first class tourist hotel on the heights of Tangier.

“Many years later Raisuni recalled his years in that horrible dungeon. I have it written out on a piece of paper. Let me read it out to you.

‘It was a small place, not much bigger than this tent, so it looked crowded, for there were nearly 100 prisoners there. To make room half of them had been fastened to the same chain, and one or two were perhaps dead, for the gaolers are always careless, and perchance there was no smith to break open the irons. It was very dark and nothing could be seen clearly. The eyes of the men were like green lamps. Do you know when you look into a hole , and unexpectedly you see twin points of light, and it is a face watching you? So the prisoners watched without moving. Some of them almost naked and shivering. Others so thin that their bones tore the rags which were on them. Truly the will of Allah is strange. The pleasure of crime is momentary and its punishment eternal.'”

Ozziel stopped his story. We had finished our meal and it was time to say the blessing after the meal, which was sung to a beautiful melismatic but Spanish sounding tune. Our thoughts were removed from the violence and chaos of Tangier, of more than a century ago, to the divine who is the giver of all good things. We sang together in Hebrew:

Sovereign God of the universe, we praise You: Your goodness sustains the world. You are the God of grace, love, and compassion, the Source of bread for all who live; for Your love is everlasting. In Your great goodness we need never lack for food; You provide food enough for all. We praise You, O God, Source of food for all who live.

This is just one prayer among many and it goes on for some time, a wonderful way to insure you digest your food and wine and take refuge in the leisure of the Sabbath. The cook then poured us all hot glasses of Moroccan tea and Ozziel continued his story.

“You would think that all this torture and harassment would have made Raiusuni less violent and more compassionate. Well that just did not happen. You see, after the turn of the 19th century Tangier became its first incarnation as a place for wealthy, eccentric European misfits.

“Let me give you a more recent example. When Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones showed up in Tangier in the late 1960s, the Tangier based American writer Paul Bowles said, ‘Brian Jones is here, rolling in money and very stoned!’

“And so along comes a wealthy American with the Greek name of Pedicaris, a man as rich as Croesus who has built his wife a gorgeous palace on the slopes of Tangier. One night Raisuni and his men crept up to the Pedicaris villa, surrounded it, overpowered the guards, tied him up, put him on a mule and walked him up to Raiusuni’s hide out in the Riff from where he sent a message to the Sultan, the Americans, British and French demanding an astronomical sum for Pedicaris release. Teddy Roosevelt sent gunboats to Tangier and declared ‘Pedicaris alive or Raisuni dead.’ (This threat got him elected president, but that is another story).

“To make a long story short, Raiusuni got his 70,000 dollars, released Pedicaris and demanded that he become the Caid or ruler of the city of Tangier. He got the job. But one must remember that when the negotiations began, the Europeans made the initial mistake of sending a go between, a tribal enemy of Raiusuni. When he arrived at Raisuni’s home he was turned over to some tribesmen who promptly slit his throat. So now Raisuni was the Caid of Tangier and I am told that the Jews of the city kept a very very low profile and kept their women off the streets, for Raiusuni had an eye for the ladies.

“Well if you think that Raiusuni was about to show himself as a moral exemplar, forget it. He set up his court just outside the Grand Socco near the French consulate. There he judged cases and dispensed his form of justice, which meant ruling in favour of whomever paid him the most money.

“He then had the convicted flogged to within an inch of their lives and revived the old Sharia law of amputations and various tortures which he made sure were carried out outside, in front of the French legation.

“He eventually was driven out of Tangier, went up into the mountains, kidnapped and got a ransom for Caid Maclean, the British appointed Scottish military advisor to the Moroccan Sultan. Raisuni made sure that he had bagpipes to play. Raisuni later told his biographer that he could not stand the sound of Scottish bag pipes.

“Finally, and in addition to the ransom, Raiusuni demanded that the British make him a protected citizen of the United Kingdom, immune from the Sultan’s authority. He got a stipend from the British, became very fat, had many concubines and dictated his memoirs in 1923, just before he died. There is a lot more to his tale but that is the general outline.

“Years later I was hired as one of the interpreters for the Hollywood film about Raisuni starring Sean Connery which was filmed around here. To have a better audience response, they turned Pedicaris into a female character played by Candace Bergen. I have both their autographs and a photograph taken with them. They were lovely to work with.”

Then Ozziel got up on to his feet and announced. “Gentlemen it is time to walk home!”

I said good-bye to Ozziel and thanked him for this local piece of Moroccan history. Hamid’s man walked me up the hill and I made it back home, tired and entertained.

The next day I pulled out my bootlegged DVD of The Wind and the Lion, the 1975 Hollywood film starring Sean Connery. Here is how it is described by one film critic.

Sean Connery brings his commanding presence and rugged heroism to the lead role of desert chieftain Raisuli in this rousing historical epic filled with eye-dazzling vistas and sweeping battle scenes. 1904 Morocco, European powers desire a foothold in the Arab world—and Raisuli is determined to stir up tribal fury against them. So he kidnaps an American widow (Candice Bergen) and her children, igniting a chain of events that include President Theodore Roosevelt (Brian Keith) wielding the big stick of foreign policy and Raisuli matching wits and sharing mutual admiration with his lovely captive. John Milius scripts and directs, bending true-life fact to serve his storytelling craft, shaping history into spirited screen legend.

The next evening, I invited Hamid, his wife Rita, and my servants Hassan and Zenobia to watch the film in dubbed Arabic at my house. They knew all about Raisuni.

I was in shock. My guests and staff laughed and guffawed through the whole thing. Scenes that I found touching, they found hilarious and vice versa. I politely waited for the end of the film and then Zenobia served us all some tea and gazelle’s horns.

I asked Hamid, “What was so funny?”

He answered, “Raiusuni murdered three of my great uncles because they once started eating a meal before he had begun to dine. He waited for them to finish eating, gave them gifts, sent them away on their mules and had his men ambush them ten minutes later. He then went to their homesteads and robbed them of every piece of silver and gold that he could find while holding the women at knife point. Oh and by the way, ‘Do you remember your visit to his palace, the Dar Asilah where you went with your friend Ozziel?’”

“Yes” I said. “It is a stunning building, a real piece of the Moroccan architectural heritage.”

Hamid continued, “Raisuni used to throw convicted victims to their death from its ramparts, the ones who could not bribe him enough to live. It is said he did so while eating lunch and listening to Moroccan musicians and, that he saw it as a form of entertainment. He was not like Robin Hood!”

Eventually I went to sleep. I had a nightmare. It was about Raisuni. He had kidnapped me. I had sent word to the Jewish community of Tangier to ransom me. I dreamt that I was awake and was anxiously waiting for an answer. I woke up early the next morning, tired. Zainab was awake in the kitchen making tea.

“Zainab,” I said.

“Yes, sidi (sir)?”

“Coffee, please.”

Table of Contents

Geoffrey Clarfield is an anthropologist at large. For twenty years he lived in, worked among and explored the cultures and societies of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. As a development anthropologist he has worked for the following clients: the UN, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Norwegian, Canadian, Italian, Swiss and Kenyan governments as well international NGOs. His essays largely focus on the translation of cultures.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast