by Justin Wong (October 2024)

Part 1

Lance Barton was famed within his academic niche, as a philologist, which was a subject that had lost its importance, at least since its heyday, when it was once seen as the dominant subject – the core of humanities, and literary studies. He specialised in ancient languages, in which he attained a fluency in Ancient Greek, Latin, Hebrew, Aramaic, as well as working knowledge in many others. This isn’t to say that he was ignorant of modern languages, and he was proficient in French, German, Spanish, and strangely enough Malay, a facet from a year in exile in his youth, such which he held onto, despite not being able to speak it with anyone.

An adequate working knowledge of several languages—particularly those dead—made him sought out in his domain of scholarship. It wasn’t unusual for him to receive letters and emails on a month-by-month basis, asking him his opinion on some linguistic matter, or getting him to assess the authenticity of a particular document, or when it happened to be dated from.

It was only now that he was asked for his expertise on a vaster undertaking, a civilisation had been excavated, under the dust of centuries, and with this, written documents, which meant an unknown tongue, which Lancelot had been asked to translate.

Part 2

As only could be guessed, Lancelot’s natural reaction considering the circumstances, was to be flattered at being asked to decipher this. As has previously been said, the tongue was of a culture previously unbeknownst to any scholar, as far as several experts could deduce. Though many of the contents of this lost people: the ruins; the buildings; pottery; objects of religious practice; and literature were found in the confines of a site within modern Lebanon.

What nation they inhabited at a particular time of history, when they were a living, breathing culture seems to be dependent on what period of time in history they existed in. Looking at their tools and other such items, this has been estimated as being between 1000-200 BC, and if anything, they were an ethnic group rather than nation, or civilisation of consequence for that matter.

Nevertheless, the fact that they left behind not only stone artefacts but texts,—a written language—was itself a remarkable feat, when one considers that other mighty cultures—Thrace for instance—bequeathed posterity nothing, nothing at least that we could understand.

As Lancelot was coming to this project without any prior knowledge, he would have to translate this, not from scraps, but nothing. A herculean feat. Though how would a philologist, go about deciphering a tongue from nothing? It would be incredibly difficult, impossible even, would it not? Well, not quite. Language isn’t quite a closed system as people assume it is. One language is a reservoir of other tongues, in much the same way that a nation is a combination of different peoples. There was a theory that these outside influences—words incorporated from alien tongues was the thing that makes a language vibrant and alive. The barring of outside influences makes the language incestuous, and as a result the culture starts to suffer the same effects of deformation and disease that plagued the royal houses of Europe preceding the revolutionary age. Ater all, a language that is free from the world, speaks naturally of a sense of isolation, how it openly eschews neighbouring powers, how it constructs a fortress against the world.

Lancelot hoped the lost culture of the Carthinos—the given name of this people—wasn’t like this. An introspective people. The chances were of course, that they weren’t, seeing as they developed the technology of writing, it suggests that they were in contact with other cultures, the Israelites, the Greeks, the Egyptians etc.

Lancelot wasn’t handed these manuscripts in a box to the office of his campus, as he might in a previous age. The texts had been digitised, the links of which were sent to him by email. He couldn’t wait to dig his fingers into this, not that he was happy to come to the endeavour blind. Knowing nothing. Learning a language was never easy, particularly in the first days, when the speaker is escorted back to Babel. Meaningful speech is undeciphered – a mass of gibberish. Hidden signs. Signs it was adamant that our hero, lift the veil up from. This was the Olympian feat our hero sought to achieve. Though I can’t say whether he either succeeded or failed in this endeavour.

Part 3

It was a considerable undertaking, an inordinate amount of time spent pouring over the stacks of scanned manuscripts, inching towards a year in fact. But he managed to decipher it. This would be an extraordinary feat for a regular philologist, though he was not a regular philologist. Which is why of all the others, he was chosen to do this. One had to remember that he was entering this project entirely robbed of sight, and this was the first time man glanced eyes upon this language, for hundreds, nay thousands of years.

Even with this being so, Lance believed, part way through this, that he was long past his abilities, which are said by some to wither in age like flowers after the days of reaching their maturity of bloom. This seemed to Lancelot to be true, preternaturally so. Especially when one looks at the easy and almost effortless way in which children learn language. As one grows up, the language instinct seems to weaken in time. Although the reason why it was more difficult for Lancelot to learn this was not because a weakening of his abilities, but the nature of the language at hand. He deciphered the tongue’s structure, its grammar, syntax, participles, he could differentiate between the language’s subjects and predicates. Though the more he tried to figure this out, the more he reached the conclusion that there was nothing to figure out. Its words contained no fixed meaning. They referred to nothing outside itself, like a map of a fantastical island, that was nowhere on the earth.

In short, its words didn’t mean anything. They signified nothing save for lines on a page, and presumably when it was alive, were ephemeral sounds that vanished after they were spoken. The reader may initially jump to the conclusion that the scholar Lancelot Barton is gravely mistaken, and it is not that the words are meaningless, but that the scholar, going into this ignorant, had not deduced their meaning.

The professor thought of this, for months in fact, though the more he analysed the words across the hundreds of manuscripts and fragments, he thought this was leading him nowhere, because he found out there was no place to end up at. The language was a journey without a destination. The word to the Carthonians was like existence to the epicurean, to be treated as thing in itself.

As I have noted, the illustrious Lancelot analysed several thousands of these words, and the thing he found out, was a given word could have different meanings across different manuscripts. You might assume that in the field of language, that this was hardly unusual, and that one word can point to several different things, much like different words can point to one thing. Being a linguist, Lancelot was aware of this, but there was no connection between how any of the words were used in which of the cases—this was across the board. This was to Lancelot, groundbreaking, a culture that formulated itself around meaninglessness, —at least in so far as language. Though with this being the fact regarding their tongue, was this the case with the rest of the institutions which comprised their society? Lancelot couldn’t think of a way in which it couldn’t be so – their unions precarious; their courts amoral; their gods, phantoms. All things naturally spring up from its foundation, language.

Words containing no fixed meaning meant that it could be whatever one wanted it to be. One could interpret one’s own meaning in relation to the text one was reading, as long as you respected the grammar it was composed in. I think it only right that I give you an example of this:

Lha Massa te minoa

Is a basic sentence that could mean “the river was high,” then again it could also mean “the apple was small.” One could see what one wanted when reading or listening to this language, and it thus could be likened to a kind of Rorschach test of words rather than blotches.

Then could one’s contemplation of this meaningless language be a better way of understanding man’s mind than the words he uses in language with meaning? I think it could.

People do not often speak the truth with the tools of their language, especially if they are particularly skilled at using them, one only has to look at the average deluder or politician as an example of this. The interpretation of a meaningless language is a more meaningful gauge. It could be likened to how certain people interpret action by other, the motivation of which, is a mirror to the observer. An adulterer might interpret the most innocuous as proof of deceit, whilst a thief might believe that everyone is out to rob him.

Could this language without fixed, definite meaning, be a tool that is used towards a similar end? Lancelot contemplated this, and the language could not merely act as a mirror to the individual, but the society as a whole. Will each generation interpret each sentence differently? Words change across the gamut of time. Of course, this is a natural facet of all language, particularly the language Lancelot ingested from his crib: English.

As an example, the word invention never meant what it does today. It means to discover, rather than to create something new, as we are now familiar with it. The same could be said not merely with words, but whole sentences, paragraphs, etc. Could this shape how they view the world, during whichever phase they were in in their civilisation.

I will give you an example of this sentence:

Erona tes lha kbona

At one moment in time this could mean a paraphrase of Bloody Mary’s final words, “Death is the beginning.” Though some might see this as being a world designed for the purposes of man, and to other people, the sentence might read quite nihilistically that “Death is the end.”

The interpretation of their language is reliant on certain unspoken assumptions of the reader. Thus, the reader is really putting words to these silent beliefs, rather than interpreting reality. Words, sentences, paragraphs, chapters, books, and libraries become a record of illusion rather than truth. This is the value of the word when used by man. I am talking about the language of the Carthonians, of course.

Though in me saying this, I am not refuting the idea of truth in itself. I think this a falsity which mirrors exactly the belief of the figure of this tale, Lancelot Barton. There is truth out in the world, to deny this would mean that everything is an opinion, that all is relative. Truth rather is stumbled upon fortuitously, Sometimes the preconceived notions we hold in which the words fortuitously mirror, are true, at other time they are false. What is the thing that severs this language from other languages, where words more or less have a fixed meaning? Lancelot concluded that the tongue of the Carthonians is the idea of language turned in on itself.

Whereas meaning within common languages is determined by the speaker, or else the writer, within their language meaning is derived instead by the listener, or else the reader.

Lancelot thought to himself that even a simple phrase could be interpreted in a multitude of ways. Would this join as one, a group of people that lacked a common understanding, that of the foundational institution of the tongue, which seeks to bind men together? Perhaps.

***

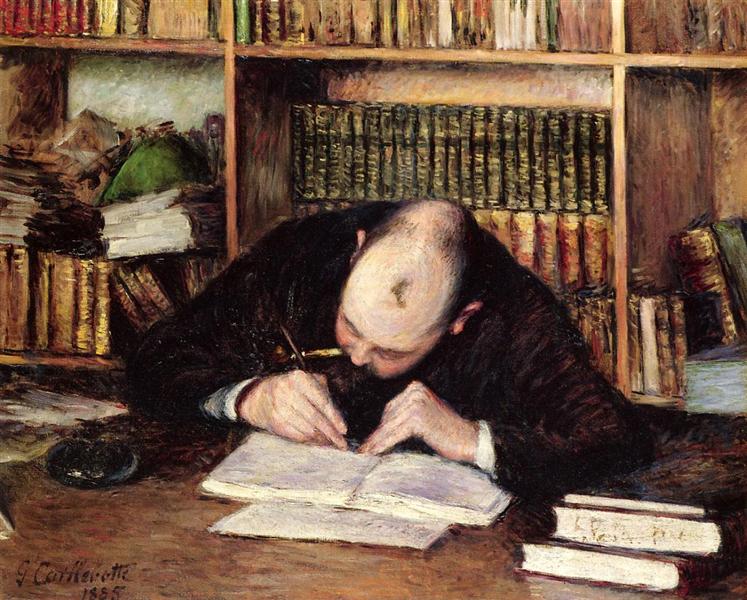

Though the more Lancelot mused upon this for hours in his lamplit study, he didn’t think that this was as preposterous as it seemed on initial impression. People use language to be interpreted in many senses. One only needs to look at literature, and poetry in particular to see this.

A hundred eyes can read one poem, to get a hundred different readings. Their language could be surmised to be likened to this. Every utterance akin to verse, everything written a bardic fragment. There was no difference between the exalted language that comprised a record of their imaginative life, and the vernacular of the streets. Anything spoken could be akin to poetry, every utterance could make the listener pause for a moment in thought.

Their society if one mused on it for a while, was the living embodiment of the time after Babel’s fall. When men didn’t comprehend each other. Then did their society fall apart by similar means? That not having the capacity to comprehend one another, made them split apart from the whole to join either neighbouring or distant nations. And did their nation disband in this strange manner? Though disband their culture did, as is evident by their no longer existing. Their fate thus being like the lion’s share of tribes throughout history, being obliterated through the fires of time.

Though for Lancelot, he wasn’t made to answer this particular riddle, but instead to uncover the mechanics of their tongue, or decipher the undecipherable, as it was. He figured this out now, as the project was in his hands, he decided it best to try to unleash his findings to the rest of the academic world.

Part 4

A month after Lancelot made his discovery, there was going to be a conference on ancient languages. Seeing as people within his discipline knew that he was working on the Carthonian project, he was permitted to speak. Though before he spoke, something strange and unexpected happened to him. He became suddenly nervous. This was unusual, for him, and throughout his tenure as a teacher, he had talked in a dozen such contexts, in public, amongst his peers. Though now it was different, which perhaps was due to the peculiarity of his findings.

Difficult as this was for him to do, he read out his lecture, saying that the language consisted of a grammar, where the words have no definition. And that all is interpretation as far as meaning is concerned. When he stopped talking the reaction from the audience was scarcely that of rapturous applause, but rather a tepid clapping of hands. It wasn’t so much this, but that after this, his colleagues began to snub him. Suspicious stares glared at him from across the room.

He chose to leave as soon as he could. But even as he left, he didn’t know exactly what people thought of his grand hypothesis—that a civilisation years ago, communicated in an inverted language.

But it was in the days and weeks after the conference that he received a slew of mail, both written and electronic, of people raising their objections to him. Some of them only wished to hurl abuse his way and claimed that he was a fraud and charlatan. There were others who said he was in over his head, and that he failed to uncover the language of this tribe, and was using this as an explanation because its meaning alluded him. This, he was willing to admit, could be a possibility, and he would thus throw his hands up if he was proved wrong, not that he thought he would. For one thing, his skills as a philologist eclipsed many of his critics. Though he received a particular note from someone who was once student of his, saying:

Dear Professor Barton,

It is wonderful to see that you a creating such a buzz in the linguistic world. I find your theory and its implication interesting, deeply so. I have read your paper three times over now. It is possible, I suppose, that there was a language once like that. Though my scepticism arises from this: why would such a language be preferable to silence? Why would a system be developed without a point? A complexity to no end? And wouldn’t their lives be rendered absurd without meaning—If everything didn’t point to another world, outside this one?

Kind regards

Kelvin

–

Table of Contents

Justin Wong is originally from Wembley, though is presently based in the West Midlands. He has been passionate about the English language and literature since a young age. Previously, he lived in China working as an English teacher. His novel, Millie’s Dream, is available here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link