Translated from the Greek

by Mike Solot (August 2019)

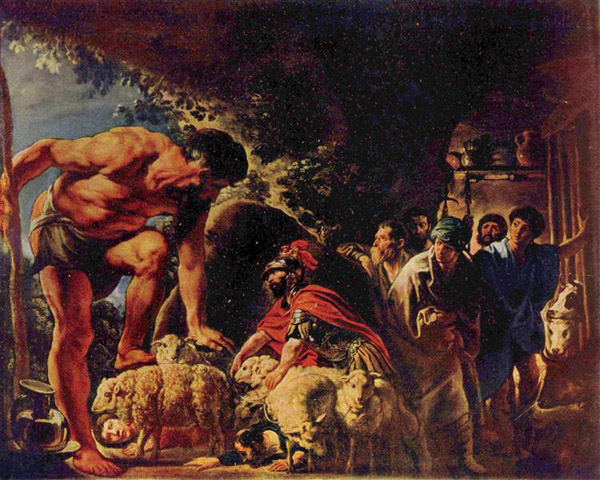

Odysseus in the Cave of Polyphemus, Jacob Jordaens, 1635

Ten years after the Trojan War, Odysseus has yet to find his way home. He washes up ashore in Phaeacia, is entertained at its court and, when pressed to identify himself, he embarks on a long narration of his wanderings since the end of the war, beginning with his raid on the Ciconês, in Ismarus, not far from Troy. After that adventure, he tells his hosts, he pointed his fleet home but was blown off course to a land where the lotus-plant grows and, as soon as he learned that “no one who tasted the honey-sweet fruit of the lotus would ever be willing to leave . . . feeding on lotus as memories of home slipped away,” he dragged his scouts back to his ships and shoved off. This is where the following passage begins. (9.105-9.566)

We raced through the swells under sail, full of forebodings,

And came to the land of Cyclopês, a tribe of barbarians,

Savage and lawless, who put all their trust in the gods.

They don’t use a plow or even plant crops with their hands

Because everything grows for them wild, unsown and untilled:

Barley, wheat, even grapes—the big, juicy bunches

That make the best wine—ripened by showers from Zeus.

They have no assemblies, no elders, no justice to guide them,

But high on the slopes of the mountains, in hollows and caves,

Each makes the law for himself and his wives and his children,

Ignoring his neighbors, who likewise care nothing for him.

Across from their coast is an island, not far but not close,

Low-lying, wooded, with hundreds and thousands of goats.

They’re utterly wild and fearless, for no mortal foot

Ever falls on the island: hunters don’t beat through the brush,

Bruising and scratching themselves as their dogs follow game

Along slopes and up ridges, and no one is there tending flocks

Or tilling the ground to grow grain. Unplowed and unplanted,

It’s empty of people—just goats, browsing and bleating.

Cyclopês aren’t sailors, you see. They don’t have the ships

Or even the craftsmen who know how to timber a vessel,

One fit for the sea, something that sailors can pilot

To cities all over the world—as so many do,

Defying the waters to know other men and be known.

With work, people like that might have settled the place,

For it’s hardly a bad place to farm. Whatever you planted

Would bear in its season: close to the seashore are meadows—

Soft, well-watered—where grapes could be grown without end,

And the ground further inland is flat, fit for the plow,

A grassland where grain would grow tall as it ripened for reaping

Year after year, so fat is the soil below.

The harbor itself is well-sheltered; you don’t have to tie down

Your ropes at the stern or heave out your anchoring stones.

Sailors can row their ships hard into sand and just wait—

For a wind that they like, or until they’re all itching to sail.

Read more in New English Review:

• That Fraud, Gropius

• The Prodigy

• The Upstairs/Downstairs Dilemma

At the head of the bay is a spring: it trickles out clear

From the mouth of a grotto and waters a big stand of poplars.

That’s where we landed, at night, deep in the gloom—

Guided, it seemed, by a god. We were moving through mists

With no moon in the sky, the fog swirling past us in front

Before closing in thickly behind, so no one could make out

The island or even the rollers that curled to the shore—

Not till we felt our keels bite as we drove up the beach.

As soon as the ships were aground we lowered our sails

And swung off the sides to the surf hissing up on the sand.

Everyone fell in a slumber, waiting for Dawn.

She came, glowing early, and opened her rose-petal fingers.

We set off to wander the island and see all its marvels

When nymphs, daughters of Zeus, began flushing the goats

From the hills and the ridges—dinner for me and my men.

We ran to the ships for our bows and our arrows and spears

And we went off to hunt, forming ourselves in three parties.

A god helped us get all the game that we wanted, and quickly.

Twelve ships I had with me then: nine goats were given

To each of the crews—but my crew alone received ten.

As long as day lingered, to sunset, we sat by the breakers

And feasted, enjoying that tasty Ismarian wine

We had won in the sack of the sacred Ciconian citadel.

Stores of the deep purple drink were still holding out well—

In fact, we had plenty; each of my captains had stowed away

Jar after jar in his ship. We gazed out across

At the land of Cyclopês, so close we saw smoke from their fires,

And even heard bleating and baaing, the sounds of their flocks.

As the sun sank to water and darkness swept up from behind

We lay down and slept where the surf hisses up on the sand.

Dawn, glowing early, opened her rose-petal fingers.

I called the whole fleet to assembly and said to the men:

“Faithful companions! The rest of you stay here and wait

While I go in my ship with my crew to look over those people,

To see if they’re savages—wild, without any law—

Or god-fearing men who will offer a welcome to strangers.”

As soon as I finished I climbed up and gave the command:

“Comrades!”—I cried—“Cast off and get to your places!”

Everyone hopped up aboard, sat down at their benches,

And all in a rhythm they smacked the sea white with their oars.

We went across quickly, landed, and noticed a cave—

High, near the edge of a headland. The entrance was tall,

Shaded by laurels, and opened out into a yard:

Great slabs of rock had been sunk between skyscraping pines

And thick, leafy oaks—a crude sort of fold, but a big one

Where dozens of sheep and goats could be penned every night.

This was the lair of an ogre who tended his flocks

Well away from his kind, shunning the other Cyclopês,

A misfit who kept to himself. He was utterly lawless,

And unlike a bread-eater, huge, a hair-raising hulk

Who was built like a big shaggy mountain, a summit apart

From the rest of its range—forested, looming, alone.

I picked out my squad, a dozen, the toughest I had,

Ordered the others to stay by the ship and keep watch,

Then left for the cave—with a skin of the heavy, sweet vintage

That Maron, son of Euanthês, had given to me.

In Ismarus he was the priest of Apollo, who guarded the town,

And he lived in the groves of the god with his wife and his son.

We spared them to show our respect for Apollo, his lord,

So he gave me a handsome reward: seven gold talents,

All of it beautifully crafted, a winebowl of silver,

And lastly this wine, filling up twelve jars in all:

Sweet and unmixed, it was heaven, a drink for the gods.

None of his servants or slavewomen knew of this store—

Only his wife and her housekeeper, nobody else.

Whenever he tasted this glowing red, honey-sweet wine,

He’d mix only one cup of liquor with twenty of water—

And still what a heady aroma rose up from the bowl!

It was divine, a vintage you couldn’t resist.

This was the wine I was taking—a big skin, and full—

Along with a bundle of food. I’d felt a foreboding,

A powerful instinct that suddenly woke up and warned me

The man I’d be facing was someone who heeded no laws

And no customs—wild, but clothed in invincible might.

We followed a path up the headland, soon found the cave,

And went in. The shepherd was gone, grazing his flocks,

But left behind much to admire: racks made of wickerwork,

All of them sagging with cheeses he’d set out to dry;

Pens packed with lambs and kids, fenced off by age—

The firstlings, the younger ones next, then the dewy newborns;

And all kinds of buckets and tubs overflowing with whey—

Things the Cyclopês had made, to use for their milking.

My men were all pleading, “Let’s carry the cheese to the ship,

Get back here as fast as we can for the lambs and the kids,

Hustle them down, toss them aboard, and shove off!”

That would have been better—much better!—but I wouldn’t go

Till I’d seen him and what he would give me. I was his guest!

It’s too bad my men didn’t find him more charming as host.

We took what we could of the cheese, kindled a fire

To make a small offering, ate a good portion ourselves,

Then sat by the embers to wait. The shepherd came in

With a huge load of wood in his arms for a supper-time fire

And dumped it inside; the banging and cracking of logs

Made us scurry in fear to a nook at the back of the cave.

He drove in the ewes and the she-goats he wanted to milk,

Keeping the rams and the billies outside in the fold,

Then lifted a big jagged boulder to close off the entrance.

Twenty-two wagons together—good ones, four-wheeled—

Couldn’t have budged it, so huge and so heavy it was.

That rock in the mouth of the cave was a hunk off a cliff!

He got down to milking his sheep and his goats in good order

And then put a suckling, a lamb or a kid, under each.

Half of the milk he thickened to curds right away,

Scooping them off into wickerwork baskets, to save;

The rest he let stand in the buckets, to drink with his supper.

He did his work briskly. Once he had everything finished

He kindled a fire, looked up and saw us, then bellowed,

“Strangers! Who are you? From where? Why are you sailing

The watery ways? Are you on some kind of business

Or are you just wanderers, pirates—crisscrossing seas

And staking your lives to win plunder in faraway places?”

The echoing roar of that voice! The size of that monster!

We felt our hearts crack as we cowered again—and yet,

Even so, I was able to step out and stammer an answer:

“We—driven off course out of Troy—Achaeans—

Winds blowing this way and that on the wide open sea,

Battered all over, aiming for home, then this way

We came. Zeus! He must have been scheming against us.

We’re proud to have fought in the army of King Agamemnon,

Whose name is the mightiest under the heavens today.

What a great city he sacked! So many men did he kill!

But now we are here, at your knees, seeking the help

Of a welcoming host and hoping, perhaps, for a gift—

Yes, the sort of thing custom says strangers are due.

Beware of the gods, O Great One! We’re here at your mercy!

Zeus is the patron of strangers and all those in need:

He is the Guest God, avenger of wrongs done to guests.”

He boomed out his answer at once—the pitiless brute:

“O Guest, you must have come far, or maybe you’re stupid.

‘Beware of the gods!’ you say, ‘don’t make them angry!’

What do we care about Thundering Zeus or his aegis?

Gods live in bliss, but Cyclopês are stronger—by far.

I don’t show anyone mercy, not you or your men,

Unless I just feel like it, whether Zeus hates me or not.

Now tell me: where did you anchor your seaworthy ship

When you came? Is it close by, or far? I’d just like to know.”

I knew he was trying to trap me, but I was too smart,

So I answered him back with some tricks of my own: “My ship?

Poseidon, who makes the earth rumble, he smashed it to pieces

By heaving it up against rocks at the edge of your country.

He pushed us too close to a cliff when a wind blew us here,

And I, with these few—we barely escaped with our lives!”

Without a reply, without even one word of pity

He lunged at us, snatching up two of my men by the legs

And slapping them down on the floor, bashing their heads in

As if they were puppies—smack!—before dragging them off;

The stuff spilling out of their skulls made a trail in the dirt,

Leaving it wet. Then he got down to his supper,

Tearing off limb after limb as he bolted their bodies,

Gulping them down like a lion, a mountain-bred killer,

Chewing their flesh, their guts, and their marrowy bones.

We could do nothing but watch these unspeakable crimes,

Screaming and crying and reaching our arms out to Zeus

As the Cyclops kept gorging, filling his belly with man-meat

While gulping his milk down unmixed. He stretched out his bulk

With his flocks all around him and instantly fell fast asleep.

I crept my way close. My beating heart told me to bury

The blade of my sword where the lungs close in over the liver;

I felt for the spot with my hand—but just as I did so

Another thought held me: we too would be dead in that cave.

We’d never be able to budge that big boulder he’d stuck

In the mouth of the hollow, even with all our arms pushing.

We spent the night anxious and fearful, waiting for Dawn.

She finally opened her rose-petal fingers and woke him.

He built up the fire, milked all his flocks in good order,

Then made sure each one of his sucklings was under its dam.

He did his work briskly. As soon as he finished he snatched up

Two more of my men, as before, and had them for breakfast.

After he’d eaten he drove his flocks out of the cave,

Lifting the stone and putting it back in its place—

As quick as an archer might snap the lid back on his quiver.

The Cyclops then led all his sheep and his goats to the slopes,

Whistling loudly away. I was left brooding,

Plotting revenge—if Athena would grant me that glory.

Next to the pens lay the limb of an olive, still green,

Torn off its trunk by the Cyclops; once it was dry,

I suppose, he was planning to drag it around as his club.

To us it seemed huge, like the mast of a black-bottomed ship,

A sea-crossing twenty-oared freighter built broad in the beam,

So long was this timber, and thick—but as soon as I saw it

I knew it was just what we needed. I straddled the pole

And hacked off a fathom or so, then ordered my comrades

To scrape it down smooth as I sharpened one end to a point.

We spun it around in the flames, charring it hard,

And buried it deep in the droppings that littered the cave.

I then had my comrades cast lots: I had to have four

With the daring to join me, to carry our spike to his eye

And jab it in hard, grinding away—once he was slumbering,

Deep in the sweetness of sleep. The lots fell to those

I’d have picked on my own, and I added myself as the fifth.

The Cyclops came back in the evening, herding his flocks

With their long, curly fleeces, and drove them all inside the cave,

Even the rams and the billies—a whim, as it seemed,

To leave none in the fold, or maybe a god made him do it.

He set down the big jagged boulder to close off the entrance,

Got down to milking his sheep and his goats in good order,

And then put a suckling, a lamb or a kid, under each.

He did his work briskly. As soon as he finished he snatched up

Two more of my men, as before, and had them for supper.

I filled a big ivywood bowl with my wine—its color,

Unmixed, was so dark it looked black—and went to the Cyclops.

“Cyclops!”—I said to him—“Look! Some wine with your supper?

Now that you’ve eaten your man-meat you might want to know

What a drink we once had in our ship. I brought it for you

As a kind of libation, a sweet one, hoping for pity

And help to get home, but you are impossibly mad!

What other mortal would want to come visit you now?

Blasphemous, stubborn, savage—you’ve outraged all order!”

He took it and drank off a bowlful of heavenly liquor,

Lustily sucking it down before asking for more:

“Be a friend—give me more wine! Tell me your name

And I’ll give you a gift, as my guest, something you’ll like.

The land here is rich: we also have grapes—big bunches,

Ripened by showers from Zeus—and their juice is delicious,

But this! This is a taste of ambrosia and nectar!”

I served him again with the fiery drink, as he asked.

Three bowls I gave him—the fool!—and three he drank down

Without leaving a drop. The wine was now soaking his wits

So I spoke to him, sweet as can be: “Cyclops, my friend,

Didn’t you ask me my name? All right, I’ll tell you—

But you must remember, you promised to give me a gift!

Noman—my name is Noman. My mother and father,

They call me Noman, and so do each one of my friends.”

His answer was nasty and quick: “Noman!”—he said—

“I think I will save you for last, after I’ve eaten

The rest of your friends. That is my present for you.”

He tilted a little, then fell, sprawled on his back.

Sleep, the master of all, had mastered him too,

Rolling his head to the side. Soon he was vomiting,

Drunk, spewing the wine and the gobbets of man-meat

Now gurgling up from his gullet. We dug out our stake

And drove the point deep in the embers to get it red-hot.

While it was heating I bucked up each one of my comrades:

“Courage!”—I said to them—“Nobody backs away now!”

As green as the olivewood was, it smoked and it sparkled

And soon it seemed lit from inside with a frightening glow,

Ready to burst into flame. I swung the tip clear

Of the fire, close to the ogre. My men came around me,

Mad with a daring some demon had breathed in us all.

They lifted the stake, steadied the point, then muscled it

Straight in the eye; I leaned all my weight on the end

As we spun it around like a ship-builder boring a timber—

His helpers, one on each side of the shaft of the drill,

Keep the bit spinning by pulling the strap back and forth—

So we were spinning our fiery olivewood pike,

Driving it deep in the eye as his blood gushed around it,

Bubbling and boiling away. The heat singed his brows,

His eyelids were scorched, and the ball itself blistered, ablaze,

Shrivelling right to its roots, which crackled and popped.

You know how an ax-head or adze-head will screech out a hiss

When the toolmaker dips it in water to harden the iron?

So did his eyeball: it sizzled when stabbed by our spike.

With an earsplitting bellow he made the rocks roar all around,

Driving us backwards in fear. He felt for the stake,

Grabbed it two-handed, then yanked it right out of his socket,

Splattering blood as he flung it away in a frenzy

And howled, calling the other Cyclopês around him—

Each in his cave on a mountainside swept by the winds.

The noise brought the neighbors, who clomped from all over

And stood at the mouth of his hollow to ask what was wrong:

“What’s all this fuss, Polyphemus?”—“Nighttime is sacred!

“You woke us all up!”—“Is somebody stealing your flocks?”—

“Is he trying to kill you? But how?”—“Is he really that mighty,

Or is he so clever he thinks he can kill you with tricks?”

The Cyclops, so big and so brawny, screamed to his neighbors,

“There’s no one who’s mighty enough! Noman is in here!

Noman is trying to kill me by using his tricks!”

Now the neighbors let fly: “So you’re there by yourself after all!” —

“If no one is mighty enough to be doing you harm,

It must be an illness.”—“Or madness!”—“Zeus made you sick,

So what can we do?”—“Better pray to your father, Poseidon.”

With that they went off. I had a good laugh to myself

At the name—my excellent cunning made fools of them all!

But there was the Cyclops, groaning and groping, tormented,

In pain. He went to the doorway and took up the stone,

Sat himself down in the middle, and spread out his hands

To the left and the right, ready to snatch up the first man

Who tried to sneak out with the sheep: The Cyclops!—I thought—

He’s hoping I’m stupid enough to do something like that!

There must be a way to beat Death, for both me and my men—

But how? Our doom is so close! He’s sitting there, huge,

What plan would be best? I wove all my cunning together

With all of my wiles—I had to survive!—till it came to me,

Something so simple, so perfect, I knew it would work.

There were plenty of rams in the cave—big, fat,

Fine-looking sheep with the heaviest violet wool.

I quietly bound them together, three rams abreast,

Twining my ropes from the pile of withes where he slept—

From the bed of that lawless barbarian. Each man I tied

To a ram in the middle; those on the sides would protect him.

Three sheep apiece for my comrades, but I would escape

With the prize of the flock, the biggest and best ram by far.

I tucked myself under his big shaggy belly—my head

To the front—by twisting the thick-curling fleece of his flanks

In my fingers and pulling up steadily, clutching and clinging,

Determined to hold. We waited, desperate for Dawn.

She came, glowing early, and opened her rose-petal fingers.

The rams and the billies ran out of the cave to their pastures,

Leaving the ewes and the she-goats behind in the pens

Where they bleated, unmilked; their udders were ready to burst.

Their master, moaning in agony, stopped every ram

As it trotted outside, and while it was standing he fondled it,

Stroking its back before letting it go. What an oaf!

He couldn’t imagine men bound to their bellies below.

My ram was the last. Heavily weighted with wool,

And with me, he trudged to the doorway. How clever I was!

Polyphemus, the mighty, petted him gently and said to him,

“Ram, my old friend, why are you coming out last?

Since when do you let all the other sheep leave you behind?

You’re always in front, charging ahead to be first

To the tender young grass in the pasture—first to the streams,

First to the fold, so eager for home in the evening.

But now you’re the last one to leave. Are you sad for my eye?

They blinded your master by dulling my brains with their wine—

That cowardly worm and his gang! Noman! I know he’s here,

Somewhere! He hasn’t escaped. If only you thought

Like your master can think—if only you knew how to talk

You would say where he is, skulking, afraid of my strength,

And I’d bash in his head, scattering everything in it

From here to the back of the cave—a little relief

For my sadness and pain, caused by that nothing called Noman!”

With that, he nudged the ram forward and out of the cave.

I held as it went through the yard, but once it was out,

Past the walls of the fold, I let go and then set my men free.

We drove off his stiff-legged sheepflock as fast as we could—

Beautiful animals, plumped up with fat—turning around

To look over our shoulders all the way down to the beach.

Our shipmates were happy to see us, since we had escaped,

But soon they were sobbing and wailing for those who did not.

I stopped them by jerking my head up and lifting my brows,

Then signalled my orders: Board all the sheep—fast!—

And launch the ship out on the water! They loaded the flock,

Hopped up themselves, scrambled to get to their benches

And all in a rhythm they smacked the sea white with their oars.

Read more in New English Review:

• Isn’t it Amazing?

• J.G. Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition and Postmodern Dystopia

• I Wonder What They Pray For

But while we were still within earshot I had them stop rowing

And bring her about, so I could yell back at the cave.

I taunted him, “Mighty and powerful Cyclops! I’m here!

Am I such a weakling, a coward? You bolted down men

In that hole where you live, but they were the friends of a hero

Who knows how to fight! You fiend! You didn’t think twice

About feeding on strangers—guests in your house!—but now

You have paid: Zeus and the other immortals avenged them!”

As soon as he heard me his anger exploded inside him.

He wrenched off the top of a crag and lofted it high

At our ship, a shot that fell close to the steering oar’s edge,

Missing by only a little; it plunged in the water

And heaved up a wave, driving us back to the beach.

Using the boat hook I pushed her away, and then,

In silence, I signalled the men: Swing her about,

Bend to your oars, and pull! They rowed for their lives,

And when we were twice as far out as we had been before

I started to shout back again—but my men closed around me,

Warning me, softly, from all sides at once, “Keep quiet,

You hothead!”—“He’s mad!”—“Why are you feeding his fury?”—

“He drove the ship all the way back to the shore with his shot!”—

“We could have been done for!”—“One little peep out of you

And he’ll let fly again with a boulder!”—“He’ll splinter the ship!”—

“Along with our heads!”—“You know he can hit us out here!”

They begged me, but I didn’t listen; my heart was too swollen

With hatred and fury. “Cyclops!”—I yelled back again—

“When somebody asks you, ‘Oh, Cyclops! Who could have done

Such a terrible thing to your eye?’—you tell him ‘Odysseus,

Sacker of Cities! He blinded me! He is the one,

The son of Laertês! The hero whose home is in Ithaca!’”

Howling, raging, in pain, he answered by screaming

“The curse! That ancient, implacable curse has come true!

There once was a soothsayer here—a tall man, imposing—

Telemus, son of Eurymus: he was the best of our seers

And reached an old age as a prophet among the Cyclopês.

He warned me, he told me how all this would happen one day,

How my sight would be stolen away by a man called Odysseus.

I always kept watch—for somebody big and good-looking,

A fighter who bristled with strength, who wasn’t afraid.

But you!—a dud, a pip-squeak, a weak little nothing

Who fuddled me first with his wine, then gouged out my eye.

Come back, Odysseus! I’ll give you that guest-gift you wanted

And pray to the sea god to carry you safely back home.

Did you know I’m his son? Earthshaker swears he’s my father,

So maybe he’ll heal me himself—if he wants to, he will,

He’ll make my eye better! Nobody else will take care of me,

None of those gods in their bliss, and no one who’s mortal.”

“Cyclops!”—I yelled back in answer—“I wish I could kill you,

Snuff out your breath, put an end to your miserable life,

And send you away to the House of the Dead just as sure

As I took out your eye—which even Poseidon can’t heal!”

That was my parting. He prayed to Poseidon, his lord,

Stretching his arms out with palms to the heavens and stars:

“Hear me, O Blue-Maned Poseidon, Shaker of Earth:

If it is true I am yours, if you say you’re my father,

Don’t let him return, this Odysseus, Sacker of Cities

And son of Laertês. Ithaca—that’s where he lives.

But if he is fated to find his way back to his country,

To walk underneath his own roof, to see all his people—

Then let him come late, after his comrades are killed,

Not in a ship of his own, but cast off by strangers—

A wretch! And let him find nothing but troubles at home!”

After he prayed—and blue-maned Poseidon did hear him—

He picked up a much bigger boulder, swung it behind him

And spun as he hurled it with all of his huge hulking might.

It plunged in behind us, not far from the steering oar’s edge,

And heaved up a billow that took us and carried us forward,

Away from the Cyclops, straight to the shore of the island.

The ships were all drawn up together, surrounded by men

Who sat facing the water, gazing across in despair.

We ran our keel deep into sand, jumped in the sea wash,

And brought out the sheep. After we split up the spoils—

Everyone got his fair share, I made sure of that—

My comrades, real warriors, gave me the big ram, the prize,

As a show of respect. High on a sand dune I slaughtered him,

Butchered him, built up a fire, then cut out his thighbones

And set them ablaze as I pleaded with black-clouded Zeus,

Son of Cronus and Master of All—but he was unmoved.

Even then he was planning to wipe out my fleet: every ship

And its crew, the men I most trusted, my loyal companions.

As long as day lingered, to sunset, we sat by the breakers

And feasted, enjoying our tasty Ismarian wine—

Till the sun sank to water and darkness swept up from behind.

Then we all went to sleep where the surf hisses up on the sand.

When Dawn, glowing early, opened her rose-petal fingers

I went down the line of my ships as I gave the command,

“Cast off the stern ropes and get to your places! We sail!”

Everyone hopped up aboard, sat down at their benches,

Then all in a rhythm they smacked the sea white with their oars.

And so we sailed on—happy to flee with our lives,

But sickened inside at the loss of our comrades, our friends.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Mike Solot was born in Tucson, Arizona, where he now lives. His translation of the Odyssey is nearly completed. An excerpt of his translation, recently published by The Society of Classical Poets, may be found here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link