How Many Assassins Were There?

The Cinematic Portrayal of Trotsky’s Murder

by Norman Berdichevsky (April 2023)

Three Figures Shot, Robert Motherwell, 1944

The role of cinema in shaping attitudes and perceptions towards historical events was cogently analyzed in Israel Through Hollywood’s Lens by Rick Richman, the subject of Mosaic’s January 23, 2023 issue. It presented a convincing case of how Hollywood has insistently rewritten the plots of many classic accounts of Jewish heroism and Israeli patriotism in films such as Exodus, Munich, and Maverick:Top Gun in order to universalize the narrative and diminish the heroic Jewish content.

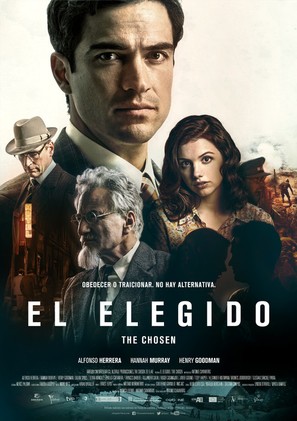

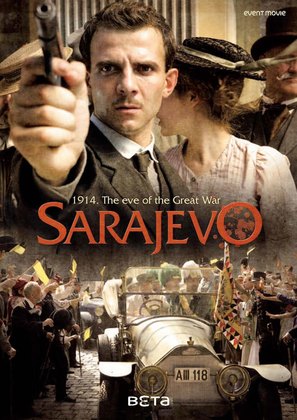

The film, El Elegido, has unquestionably accepted the long-held narrative that Sylvia Ageleff was an unwitting dupe who made possible the assassination of Leon Trotsky in Mexico in 1940. The chosen narrative the film follows ignores critical evidence on many levels and prevents the viewers from gauging the full significance of the Stalinist plot. It can be sharply contrasted with another film, Sarajevo (Das Attentat), an accurate dramatic film by Austrian director Andreas Prochaska, starring Florian Teichtmeister and Edin Hasanovic.

Sarajevo (Das Attentat) was produced in 2014 by both German and Austrian television to coincide with the one hundredth anniversary of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the outbreak of World War I. It focusses on the character of Leo Pfeffer, the examining Austrian magistrate in Sarajevo appointed to handle the investigation of the assassination.

Pfeffer, a Jew (obliged to convert in order to guarantee his post) , is outraged at the apparent gross incompetence of the local authorities in not preparing adequate security measures for the Archduke’s visit to Sarajevo. Leo is a brilliant, highly motivated, and competent investigator, but he must tread carefully.

Any failure to satisfy the higher authorities in Vienna will cost him dearly, probably ending his career. He is aware that his Jewish identity will inevitably subject him to multiple pressures. A failure to find and punish the guilty will condemn him of the suspicion that, like all Jews, he is guilty of insufficient Austrian patriotism and loyalty to the House of Hapsburg.

The film El Elegido, 2016, was written and directed by Antonio Chavarrias and produced on site in Mexico. It reveals the elaborate single-minded preparations of the plot to murder Trotsky thereby eliminating Stalin’s great rival and threat to inherit power in the event that the Soviet state fails to survive the world economic crisis of the 1930s or is defeated by the Nazis in their invasion of the USSR in 1941.

The film El Elegido, 2016, was written and directed by Antonio Chavarrias and produced on site in Mexico. It reveals the elaborate single-minded preparations of the plot to murder Trotsky thereby eliminating Stalin’s great rival and threat to inherit power in the event that the Soviet state fails to survive the world economic crisis of the 1930s or is defeated by the Nazis in their invasion of the USSR in 1941.

The film follows the actions of three principal characters, Trotsky, the Stalinist assassin, Ramón Mercader and Sylvia Ageleff, ostensibly nothing more than a devoted Brooklyn Jewish communist, librarian and social worker who arrives in Mexico to work for her declared, devoted idol, Leon Trotsky. Once there, the narrative pursued by El Elegido sticks firmly to the classical and more than eighty-year-old conclusion that she had been cynically exploited by Mercader, a dedicated Soviet agent trained by his fanatical communist mother Caridad, in Spain, to make any sacrifice (including his life) in service to Stalin. Mercader is taught to ignore every human emotion of compassion and decency. His dedication is demonstrated by willingly killing his favorite pet dog on command from the NKVD. He and his mother were Catalans who had been Communist Party members in Spain during the Spanish Civil War and found refuge in the USSR after the defeat of the republican forces.

NKVD agent Leonid Eitingon, who operated in Spain under the alias of General Kotov, had a long–running love affair with Ramon’s mother. He trained her son in Moscow in 1937 in the ways of espionage and guerrilla warfare and was the brains behind the assassination. He must have also chosen Sylvia and correctly believed that she would be attending a secret conference of Trotsky’s Fourth International (about which the NKVD had been tipped off) in France in the summer of 1938. The NKVD used a wavering Trotskyite and acquaintance to travel to Europe with Sylvia and set her up with Mercader via another agent. Using several aliases and phony biographical details, Mercader allegedly swept her off her feet as the debonair, wealthy and handsome Trotskyite sympathizer who followed her to Mexico where she had become one of close associates.

Several crude attempts to assassinate Trotsky including a machine gun attack on the Trotsky compound are foiled by the Mexican police, but the NKVD agents have prepared Mercader for years to use every means available to achieve their goal; the easiest route to gain access to Trotsky is by stealth and deception of his innermost circle. This was the strategy used by the plotters. Sylvia is regarded by Trotsky’s bodyguards as a devoted follower and secretary in the compound where Trotsky was then virtually a prisoner, thereby giving her ostensible fiancé, Mercader, direct access to him.

The film also explains the use of a mountaineer’s ice axe as the murder weapon. Any firearm would have immediately aroused suspicion and Mercader had been welcomed by Trotsky and his bodyguards as a close friend of Sylvia whom Trotsky and his protectors had been very sympathetic to. The ice pick was explained as part of the tools he used as an amateur geologist. Only such a tool or “household item” already present in the kitchen and able to be hidden in a fold of clothing provided the ideal unsuspected weapon.

The film also explains the use of a mountaineer’s ice axe as the murder weapon. Any firearm would have immediately aroused suspicion and Mercader had been welcomed by Trotsky and his bodyguards as a close friend of Sylvia whom Trotsky and his protectors had been very sympathetic to. The ice pick was explained as part of the tools he used as an amateur geologist. Only such a tool or “household item” already present in the kitchen and able to be hidden in a fold of clothing provided the ideal unsuspected weapon.

After drinking tea with Trotsky, Mercader found his chance. He used the ice axe intended for mountaineering to strike Trotsky in the skull and knee. Amazingly, Trotsky managed to fight back and call his bodyguards. He grappled with Mercader, and even spat in his face and bit his hand during their altercation. Mercader was beaten by Trotsky’s guards and taken to prison. Trotsky was removed from the scene of the crime and operated on, but he died 25 hours after the attack. Mercader (using a false Belgian passport under the name of Jacque “Mornard” was swiftly arrested and tried, claiming he had murdered Trotsky because the exiled communist leader would not allow him to marry the woman he loved.

Mercader then served 20 years in prison under his assumed identity as the Belgian Mornard, but his real name was revealed through a counter-intelligence project. While the Soviet Union denied any involvement in the murder of Trotsky, Mercader moved to the USSR in 1961 following his release and eventually was given the highest Soviet award “Hero of the Soviet Union,” usually given only to soldiers for outstanding heroism and bravery; It was awarded personally by Alexander Shelepin, the head of the KGB. Mercader divided his time between Czechoslovakia, Cuba (where he was the advisor of the Foreign Affairs Ministry), and the Soviet Union for the rest of his life. He married a Mexican woman in prison and had two children. In 1979, he died in Havana in 1978 of lung cancer and is buried under the name Ramón Ivanovich Lopez in Moscow’s Kuntsevo Cemetery.

The Common Link Between the Ostensibly “Minor” Jewish Characters Sylvia Ageleff and Leo Pfeffer

To many of their contemporaries, fellow comrades and superiors, Leo Pfeffer was one of many “Moishes” in the Diaspora of the last two thousand years: competent and skilled, but unable or unwilling to take final responsibility for a decision that could only have been taken at the highest level by a logical candidate someone from the majority Germanic population and ruling class such as Friedrich von Wiesner, a high official in the war ministry who held posts at the universities of Vienna and Prague. He later became the Austrian Minister of Commerce towards the end of World War I.

What we know for sure is that Pfeffer followed a time-honored strategy of many assimilationist-oriented Jews in Europe who converted to Christianity to protect or forward their careers. Sylvia blindly ignored her Jewish background in an attempt to identify with what she considered a much larger and higher cause that would benefit all of humanity. In so doing, both of them tried the patience and “tolerance” of their comrades or superiors who either doubted their effectiveness (Leo Pfeffer) or made costly allowances for it (Sylvia). Many Zionist leaders had correctly predicted that such an outcome was likely to be expected from Jews who had made a commitment to an ideology that promised a classless society in which national, ethnic and religious differences would all be dissolved.

According to the film, Sylvia would never be able to forgive herself for her “innocent mistake.” She was forced later in life to give testimony several times in Mexico and the United States, reliving the tragedy, her humiliation, and shame. According to the conventional version of events repeated in El Elegido, she was nothing more than a naïve and homely social worker from Brooklyn who, at home in America, had been a member of the Socialist Worker’s Party, a Trotskyite splinter group.

This is the most commonly accepted narrative of “Poor little Sylvia.” It has, however, encountered numerous objections, most significantly from the revelations that the American Socialist Labor Party which was riddled with Soviet agents and by release of GPU-KGB secret police documents in 1991 following the collapse of the USSR and providing corroboration that the published findings of the Security and Fourth International (Totskyite ) in 1975-78 were correct—Sylvia Ageleff played a complicit critical and willing role in the setting up the assassination scenario of Mercader.

This narrative refutes the previously unchallenged account that she was an innocent dupe. It was invented by Ageleff and Mercader in the immediate aftermath of the assassination. Sylvia had to be accepted as an emotionally distraught lover—a woman without agency, a meek Jewish librarian and so stupid as to be incapable of recognizing the transparent and bizarre contradictions in the mysterious life story and activities of Mercader, the man with whom she had been sleeping for nearly two years. In the film, the Mexican police come to wrong conclusions and are convinced that prosecuting her would only make them appear heartless.

How Hollywood Scripts Avoided Offending our Soviet Ally

During the period of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Non-Aggression Pact in which the Nazis and Soviets were close allies, the Soviet attack against Finland in December 1939 provoked screenwriter Philip Dunne and actor Melvin Douglas to propose that the Motion Picture Democratic Committee, a group of activists identified with the Democratic Party, condemn the invasion. A hardcore insider group of Communist Party members using the organization as a congenial front insured the defeat of the resolution.

In his 1980 memoir, aptly named Take Two: A Life in Movies and Politics, Dunne wrote “All over town, the industrious communist tail wagged the lazy liberal dog.” And so it has been ever since. This was noted in the 1930s by screenwriter Ayn Rand, the only one in Hollywood who had actually lived under communism. Communist party member Dalton Trumbo, regarded as the highest paid screenwriter in the movie business in Hollywood was a Communist Party member and viewed his profession as “literary guerrilla warfare.”

In 1941, before Pearl Harbor, religiously towing the Party Line, Trumbo wrote a novel The Remarkable Andrew, in which the ghost of Andrew Jackson appears in order to warn the United States not to get involved in the war. This was so blatant that even Time Magazine sarcastically commented that “General Jackson’s opinions need surprise no one who has observed George Washington and Abraham Lincoln zealously following the Communist Party Line in recent years.”

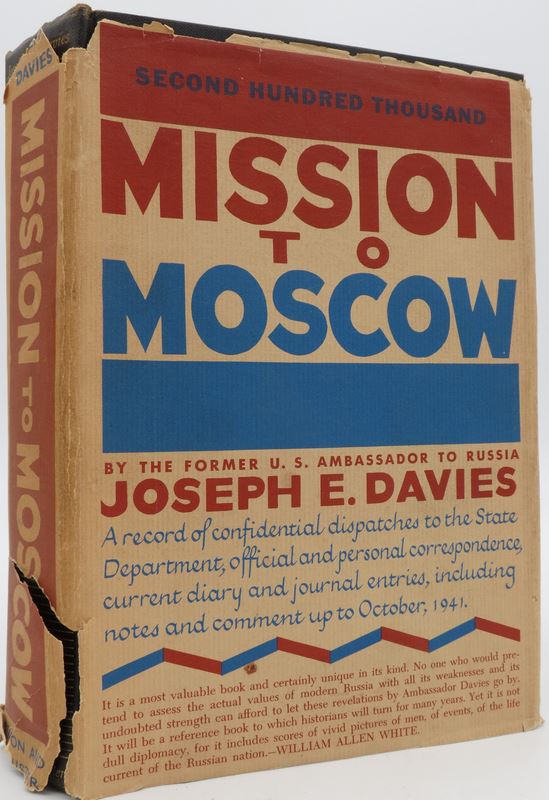

To gauge Trumbo’s influence and others in whitewashing Stalin, one has to view such films as North Star and Song of Russia (both 1943) that portray the USSR as a happy land of industrious peasants and workers living in simplicity but with dignity. Even worse was Mission to Moscow (1943) starring no less a dignitary than Walter Huston dignifying the purge trials and explaining how Russia had generously offered Finland five times more land (all worthless tundra) in a border adjustment to acquire territory and valuable military positions in in proximity to Leningrad. Huston had starred in many films most notably a Biography of Abraham Lincoln that had established his reputation as a man of the highest integrity and demonstrated Trumbo’s great skills in manipulating every aspect of the cinematic art, starting with appropriate casting.

Although the film El Elegido in no way hides or diminishes the evil of the Stalinist plot to murder arch-rival Trotsky, it raises doubts regarding its reluctance to include Sylvia as an accomplice. This traditional narrative diminishes the extent of Stalin’s pervasive unrelenting network of brutal agents operating on a worldwide scale to infiltrate and compromise Trotsky’s efforts to undermine Stalin.

Although the film El Elegido in no way hides or diminishes the evil of the Stalinist plot to murder arch-rival Trotsky, it raises doubts regarding its reluctance to include Sylvia as an accomplice. This traditional narrative diminishes the extent of Stalin’s pervasive unrelenting network of brutal agents operating on a worldwide scale to infiltrate and compromise Trotsky’s efforts to undermine Stalin.

Trumbo bragged in The Daily Worker that thanks to him and communist influence in Hollywood, the Party had quashed adaptations of Arthur Koestler’s anti-communist works, Darkness at Noon and The Yogi and the Commissar. It is precisely this point that most of the House un-American Activities Committee missed in its investigations; the internal network within the screen writers’ union in sympathy with the party line rather than the specific content of individual films that might be excused as part of the war-time patriotic effort to cast “Our Soviet Ally” in the best possible light.

What is all the more notable is that the House Un-American Activities Committee was at first strongly supported by the Communist Party–USA (CPUSA) when first introduced in 1933 on direct orders from Moscow because it was involved in uncovering Nazi and then later Trotskyite activities.

Each stage in the preparation of the plot to murder Trotsky.

At each stage in the preparation of the assassination, it was Sylvia Ageleff who played the decisive role in integrating Mercader into the Trotskyist movement, and, ultimately, into his fortified villa. In 1940, the Mexican police conducted the only contemporaneous investigation. She was arrested and imprisoned by Mexican police as an accomplice. They charged her with murder and prosecuted her. Sylvia appears to have been saved from conviction by the diplomatic intervention of American authorities.

Apparently, we are asked to believe that the young woman, desperate for affection, the young SWP member was quickly seduced by the dashing Jacques Mornard, one of the many aliases used by the assassin, unsuspected by Sylvia in the course of an intimate affair with him that lasted nearly two years and that she overlooked or dismissed the glaring contradictions in his cover story, multiple aliases, mysterious business activities and unexplained large amounts of money. Mercader stuck to the story given to the Mexican police, “Sylvia had nothing to do with this.” After returning to the United States, she moved on, spending the remaining 55 years of her life in affluent anonymity.

Eventually residing in a comfortable Manhattan apartment, Ageleff died in 1995 at the age of 86 without leaving behind any account of her own. The SWP maintained total silence regarding Ageleff after Trotsky’s death, dreadfully embarrassed by their failure to protect Trotsky, allowing her to retreat into anonymity. The SWP’s newspaper, The Militant, did not report on her arrest by the Mexican police after the assassination, and in 1950, when Ageleff appeared before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, it made no notes of her testimony.

Her family’s history and background should have raised immediate suspicions. Sylvia’s parents had had four daughters: Lillian (1902–1986), Hilda (1906–1997), Sylvia (1909–1995), and Ruth (1913–2009); and two sons: Allan (1903–1997) and Monte (1907–1965). Sylvia came from this highly political family, and three of the sisters entered into socialist politics in their youth. Hilda had travelled to the Soviet Union and interviewed Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin’s widow, who was a member of the Soviet Union’s Commission on Public Education. This trip took place two years after Trotsky had been exiled to Turkey, when his followers were being persecuted by the Stalinist regime in the Soviet Union.

According to the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Hilda Ageleff told of her interview with Madam Lenin which had been the high spot of her three-and-a-half month Russian trip and had been granted special interview privileges because she had visited many kindergartens and the nurseries which care for the children in the communal farms and cities and she wished to ask Mme. Lenin many questions.

How likely is it that Sylvia’s sister had reported so favourably on Stalin’s Russia at a time when Trotsky was already in exile by Stalin and his life threatened? At the very least, the siblings and parents met what the FBI had always referred to as “fellow travellers” of the Stalinist regime.

Sylvia’s younger sister, Ruth was also a member of the SWP and both sisters were fluent in Russian and had worked for Trotsky and prepared the way for her sister’s enjoyment of his confidence. Both, after all, had been active SWP members in America. Sylvia was fluent in French in addition to Russian and English. She completed both a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in child psychology and had been active in performing drama while in high school. Her master’s thesis dealt with the topic of “suggestibility,” which she defined as an inclination to readily and uncritically adopt the ideas, beliefs, attitudes, or actions of others.” Could one have wished or better training to be a double-agent?

What is relevant about her Jewish identity is that she was instrumental in the assassination by playing on the sympathy of Trotsky’s bodyguards. Had she not been Jewish (like Trotsky himself) and eliciting sympathy from Trotsky’s bodyguards, there would most likely have been no point of access for the assassin to wield his ice-pick and change history. She acted as a polar opposite to Leo Pfeffer’s noble efforts to honestly search for the truth and not be intimidated by the reactionary elements within the Austro-Hungarian Empire to unleash a world war in order to crush Serbian and pan-Slavic opponents.

Lars Hedegaard came to mind immediately after viewing the two films. I pay tribute to his constant moral compass, like that of Leo Pfeffer in Sarajevo—whatever the shifting now meaningless terms of Left and Right. The film El Elegido reveals the error of all those who never change blind loyalty to sterile ideologies.

Table of Contents

Norman Berdichevsky is a Contributing Editor to New English Review and is the author of The Left is Seldom Right and Modern Hebrew: The Past and Future of a Revitalized Language.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast