If TV’s So Good For You

by Jeff Plude (May 2019)

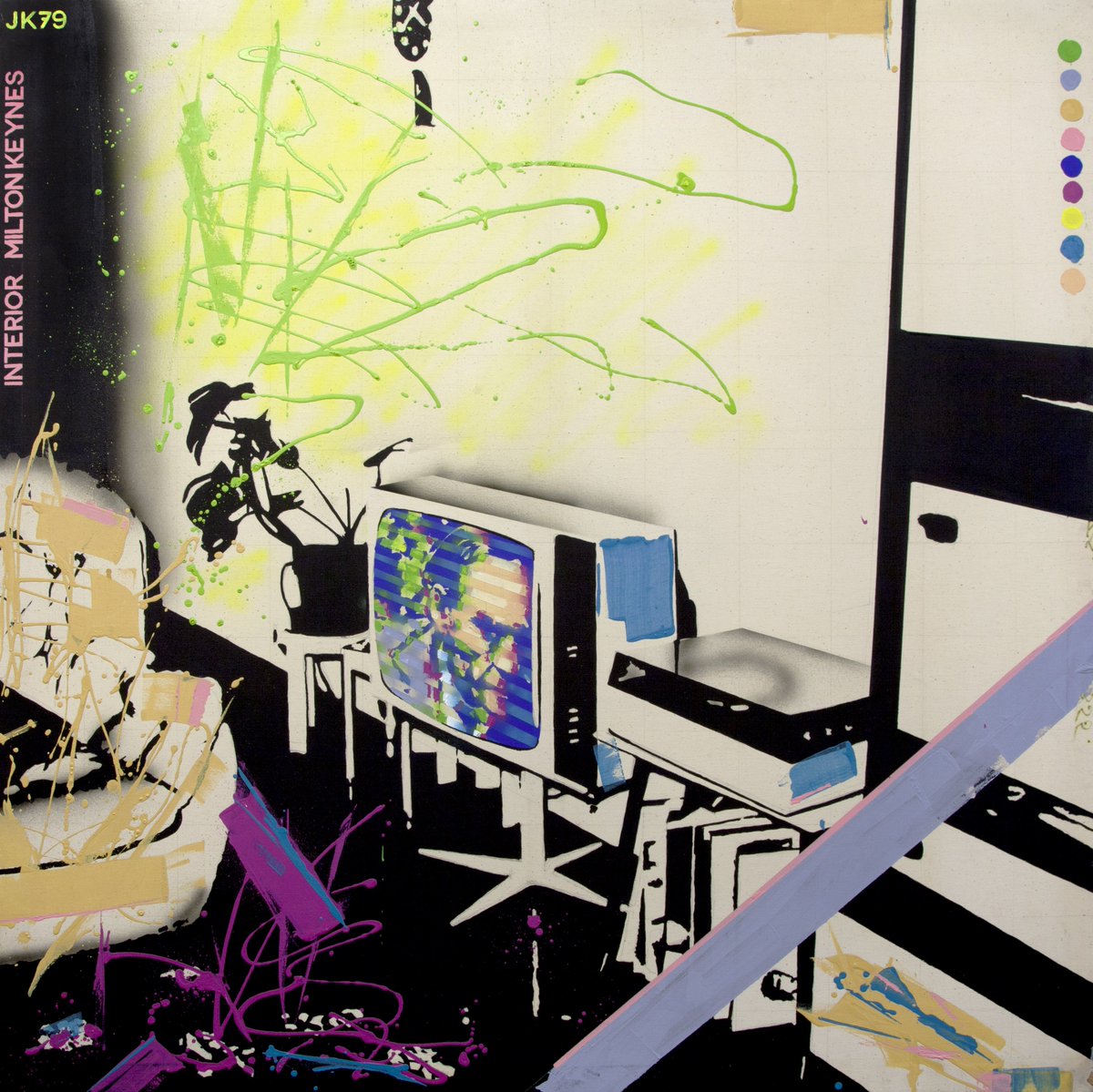

Interior Milton Keynes, John Keane, 1979

“What! You don’t have a TV!” the longtime attorney booms across the large round table as we are eating our salads at the firm’s Christmas party.

The half-dozen other people at our table look at me and my wife. I stare down at my plate wishing I could crawl into it like Alice through her mirror, sort of how I used to think that people lived in the TV itself when I was a little kid. That was back when the screen was black and white and many shades of gray, but it still seemed like magic. Eventually we upgraded to a floor model set, which had a dark brown wood cabinet and a wire that was connected to the antenna on the roof and the glass tubes in the back that our TV repairman, a bald, soft-spoken man with black-frame glasses, used to fiddle with as he knelt behind the TV.

The same thing had happened at the firm’s Christmas party the year before. That time the stunned person was a retired salesclerk, the husband of one of my wife’s colleagues. The couple was also sitting next to us the night the lawyer outed us.

I don’t remember exactly what sparked the latest instance, but it’s usually from the same general question: do you know such-and-such program or show or game or commercial? We’re often asked this, sometimes even after we explain that we don’t own a TV.

I’ve suggested to my wife that perhaps she avoid revealing that we don’t have a TV, which makes us seem almost unpatriotic. Television, if not an American invention, is thoroughly and quintessentially American; one of the oldest television stations in the world, WRGB in Schenectady, New York, broadcast the first daily programs in 1928, and TV became one of the United States’ most influential exports. Though my wife tends to see it as a worthy cause, I tend to see it as a lost cause.

Read more in New English Review:

• Light Thoughts on Kingsley Amis

• Plumbing the Depths

• Intuition and Virtue in Miguel Delibes’ Las Ratas

So, this night, when we’re asked if we’ve seen such and such, she blithely announces: “We don’t have a TV.”

It’s happened so many times that when the next question is inevitably asked, I now have a canned answer I deliver, like I’m delivering a punch line. Like when the retired salesclerk then asked me, “What do you do?” I deadpanned, “We read, we talk, we argue.” I used to end the line with “we get bored,” but that hits a little too close to the epicurean nerve. Boredom now has such a low threshold that nothing short of explosions or exposed flesh will do.

I tried to do the same routine at this year’s firm Christmas party. It didn’t even get a smile. If only I’d had a laugh track. There’s probably a mobile app for one, but we tend not to use apps either.

Sometimes my wife launches into a full-fledged defense, making a case for our not having a TV. But she won’t win any Clio awards with her efforts. She usually tells whoever it is that we read, we drink coffee and tea, or a glass or two of beer or wine at night, we listen to music, we play backgammon, we watch movies on our twenty-inch desktop computer monitor. “We watch movies once a week, on Saturday nights,” I sometimes add on cue. “It’s like the 1940s at our house.” In fact my father used to talk about going to the movies once a week in the early half of that decade, when his parents would give him, the second oldest of eight kids, a quarter and he’d walk the mile to the small city downtown on Saturday afternoon and spend it on a movie and a hotdog and soda.

“So, I guess I can’t talk about sports with you then?” the salesclerk said to me after he recovered from his initial shock.

This is a common refrain from men. I said, no, he couldn’t. But I remember well when I did watch pro football, wasting three to four hours at a time, whether it was a good game or not—it had been quite a while since I’d watched back-to-back games, long before we got rid of our last TV. But my wife and I still watch the Super Bowl, which for the past few years has been streamed free on the internet. Before that we used to go to a pub and watch it.

We put our last TV on the sidewalk outside our apartment on New Year’s Day 2007, though we’d stopped watching it, for the most part, three years before that. It had what is now a Lilliputian twenty-inch screen set in a bulky silver plastic cabinet. I remember watching the Winter Olympics on it in 2006. I grew up watching the Olympics on TV, but from the snippets I’ve seen since then I don’t find the games worth watching anymore anyway. They’re supposed to be a triumph of sports over politics (except in 1916, 1940, 1944, 1980, and 1984), but wars aside, political correctness is an opponent it’s unlikely ever to defeat.

Not an hour later the sidewalk was empty. Our TV was gone. It felt strange. I felt almost queasy. A dozen years later our only regret is that we didn’t get rid of it sooner. I now consider it a turning point, one that paid off in many ways. I only wish I’d smashed the screen so it was unwatchable, though the person who scarfed it up was almost certainly not a new television viewer.

Which reminds me of an ad I saw on a bus shelter in downtown San Francisco that was my first declaration of war against that old false friend. It was late July 1998 when I wrote a poem about it (which is unpublished) called “If TV’s So Good for You.” It begins:

“If TV’s so bad for you,

why is there one

in every hospital room?”

the smug copywriter taunted

in simple black letters on

a bare lemon background

on the side of a bus shelter.

After three stanzas cataloging the damage I’d like to inflict on my set, I delivered the literary coup de grâce:

It’s true that

every hospital room

has a TV,

but the sheets

reek of death.

A TV isn’t fit

for a living room

let alone a dead one.

A TV is a blindfold

for the condemned.

The last two verses are perhaps hyperbolic. But that was the beginning of the end of what up until then had been my lifelong up-and-down affair with TV.

But I’d had my suspicions long before I saw the shameless, cocky ad. In the late 1980s I was in graduate school and had a mountain of reading I was supposed to be doing. Instead, I used to stay up half the night watching Charlie Rose interview (or I should say ingratiate himself with) the latest media darling, or prostitute, of the moment. I don’t remember why or what prompted it, but I suddenly decided to not watch TV for a whole weekend. Could I do it? It was hard. I felt restless. I don’t remember if my wife and I went out for dinner or drinks anywhere on Saturday night, but if we did it was only for a half dozen hours at most. I remember we talked and played albums, and at one point I was draped across the sofa at some odd angle. But then it was over, and the surreal feast resumed for two decades without a reprieve.

TV is indeed surreal, which I only realized when I’d been separated from it for much longer than a weekend or even a month, which is probably about how long most viewing fasts last. Unlike movies, TV is continuous. TV is also ubiquitous, on in homes and public places at all hours of the day and night. And it’s teeming with genres—talk shows, game shows, talent shows, soap operas, cartoons, sitcoms, dramas, telethons, crime shows, reality shows, cooking shows, travel shows, news shows, sports. And each program itself is fragmented, not only confined to a relatively short duration but chopped up by unrelated and diverse interruptions, better known as commercials. It’s self-contained and self-referential. As Marshall McLuhan might say, it’s decontextualized.

Mr. McLuhan is perhaps the most influential theorist on the profound effects of media, especially television, which took center stage in the early 1950s when he was a fortyish professor at the University of Toronto, where he became head of the Centre for Culture and Technology. His most popular and influential book Understanding Media was published in 1964, containing the now cliché epigram “The medium is the message.” Reading him is a little like sitting at the foot of a well-read classically educated Zen-like grandfather who likes to amuse his grandchildren with cryptic pronouncements, such as distinguishing between “hot” and “cool” mediums (TV is “cool” because it lacks detail and requires the viewer’s participation to fill it in, while books are well-defined and therefore “hot”). The result is somewhat mesmerizing but ultimately mystifying.

Perhaps most interesting of all is that despite Mr. McLuhan’s considerable ruminating and theorizing about television, he apparently didn’t watch it himself, according to his colleagues. However, that didn’t stop him from appearing on TV. How else to reach the lost? Coincidentally, it also made him a household name.

He may have shunned TV himself, but he seemed to play the role of its neutral expositor. But that was fine for him. Mr. McLuhan didn’t grow up in front of the idiot box, the boob tube, the glass nipple hour after hour, day after day, from toddler to manhood. I did.

How did I become a juvenile TV addict? Quite naturally, like any American kid who didn’t grow up with the Amish, or some cult. The first show I remember loving was Batman, which urged me to tune in next time at the “same Bat-time, same Bat-channel!” I also liked science fiction—The Twilight Zone and Star Trek but especially Lost in Space (also reportedly a favorite of John F. Kennedy, Jr.), whose Will Robinson was about my age and interested in science just like I was, though my father was no astrophysicist and I was stuck on Earth. I didn’t care for detective shows, but I never missed Dragnet, and I was entranced by Joe Friday’s rapid-fire lectures. I also enjoyed the over-the-top social satire of All in the Family, though I didn’t understand the episode in which Meathead was having problems with his wife, Gloria, because he was “stuck in neutral” (I was ten years old); I even bought an album of the show so I could hear Archie and Edith Bunkers’ Queens accents any time I wanted. And there were sports, which I couldn’t get enough of (thankfully ESPN was a decade away). Up until around 1970, when a limited form of cable arrived in our area, the only channels we got were the three major networks and PBS. At midnight or so, stations “signed off” with the national anthem till dawn. In the small town where my wife grew up in New Hampshire, they had only NBC. Now, of course, there are whole galaxies of channels and programs.

Read more in New English Review:

• Children and the Great Blur

• Glass, Germs, and Steel: Mayor De Blasio’s Draconian Public Health Policy will Fail

• Dysfuntion Junction

I’d watch almost anything. As you may have guessed, I didn’t come from a family who read books, though my parents religiously read the local newspaper. Unlike my mother, my father didn’t care much for TV. He wasn’t around much anyway. But when he was, he used to like The Honeymooners, which I also came to like. My wife and I even quote from it on occasion for a laugh, but I have a cousin who can’t seem to talk enough about the late-1950s sitcom and its hapless blue-collar hero, Ralph Kramden.

The point is that I didn’t watch programs on TV so much as I watched TV, whatever was on, which I continued to do into early adulthood. Though as a reporter and then a writer, I spent more and more time reading. And my wife is a painter. Both of us found that TV seemed to clog our creative arteries.

Some will say you can be both a TV viewer and a serious book reader, that the two can coexist. But as Schopenhauer said: “A precondition for reading good books is not reading bad ones: for life is short.” Replace “reading bad ones” with “watching TV” and I think you have a formula that’s equally true. It’s hard to say how much TV the average American now watches each day, with millennials preferring video on the web, either free or in the form of Netflix and other online services. But even if it’s for a few hours a day on average, that’s a lot of unread good books, or a lot undone of anything else of real importance. Some even “binge-watch” whole seasons in a marathon session or two instead of watching regularly. Whatever the true numbers, I don’t imagine anyone on their deathbed regrets they didn’t watch a little more TV.

August Wilson, who won the first of two Pulitzers in 1985 for his play Fences, once told New York Magazine that he watched “very, very little” TV, and had never seen Seinfeld or The Cosby Show (he also went eleven years without watching movies). “I’d rather read,” he said. In a 1989 interview with the Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism at the University of Kansas, he lamented TV’s devastating effect on the theater and the new wave of playwrights:

For the most part they’re not very good and I think partly the reason for that is the influence, the tremendous influence that television has had. I think this is the first generation of playwrights who actually grew up on TV. As a result of that, they have had a lot of plays resemble television sitcoms and that’s because as opposed to reading literature, they watch TV . . . So, as a result, I think that’s why they produce the kind of work they do. I think it’s had a bad influence on writing . . .

I, too, think that literature and TV are natural enemies. One promotes reason, reflection, imagination. The other titillates but ultimately numbs, hypnotizes, lobotomizes. No one vegges out with a novel (unless it’s genre fiction, which on the lower end can be close to TV fare). Even a mediocre book is slow food for the soul.

Before TV, for nearly three centuries Americans apparently were downright bibliophiles, according to Neil Postman, who was a professor and chairman of the Department of Culture and Communication at New York University until just before his death in 2003. In his 1985 book Amusing Ourselves to Death, Mr. Postman shows how the U.S. was a nation of voracious readers even in uteroMayflower carried several books in its cargo, including “most importantly” the Bible. And the original Colonists’ immediate descendants were no different:

. . . there is sufficient evidence (mostly drawn from signatures) that between 1640 and 1700, the literacy rate for men in Massachusetts and Connecticut was somewhere between 89 percent and 95 percent, quite probably the highest concentration of literate males to be found anywhere in the world at the time. (The literacy rate for women in those colonies is estimated to have run as high as 62 percent in the years 1681-1697.)

By contrast, Mr. Postman says, the literacy rate in England during the same period (when Milton’s Paradise Lost and Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress were published) was no higher than 40 percent. He believes this is because the Colonists came from more literate areas or parts of the population—in other words, they were Christians. And from 1650, he says, almost every town in New England passed a law that required a “reading and writing” school to be established. They considered such literary schooling to be not only “a moral duty” but an “intellectual imperative.” He also cites probate records showing that 60 percent of the estates in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, from 1654 to 1699 contained books, and that 92 percent of those book owners had more than just a Bible in their homes. And what’s more, though they came to the New World seeking religious freedom, they didn’t just read theological texts:

In fact, between 1682 and 1685, Boston’s leading bookseller imported 3,421 books from one English dealer, most of these nonreligious books. The meaning of this fact may be appreciated when one adds that these books were intended for consumption by approximately 75,000 people then living in the northern colonies. The modern equivalent (in 1985, my addition) would be ten million books.

That salutary trend seems to have led to the American Revolution, when Thomas Paine’s Common Sense galvanized and unified the Colonists to fight for their freedom. The short book was published in January 1776, and by March of that year had sold more than 100,000 copies.

Mr. Postman believed that television had supplanted the print way of life and commandeered the whole culture. It did this, as his title suggests, by turning everything—news, politics, religion, education—into entertainment, and what it couldn’t make entertaining it ignored. So whatever was on TV’s unofficial blacklist ceased to exist, for the most part, in the public mind. The long and benevolent reign of print, largely responsible for America’s prodigious growth and prosperity—if not its very creation—died, not with a bang, but with a laugh. It’s like the “feelies” in Brave New World, according to Mr. Postman: the masses gladly hand over their freedom, their minds, and their very souls for perpetual pleasure.

However, it was another book that made me finally consider getting rid of our TV for good. With the not very promising title of Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, it nevertheless intrigued me as I thumbed through it in 2004 in Barnes & Noble on 82nd Street and Broadway in Manhattan. Jerry Mander, the author, was a former ad executive in San Francisco who knew firsthand TV’s vast power to manipulate a mass audience and sell them whatever big corporations wanted, regardless of whether it eventually harmed viewers and consumers or not.

Mr. Postman didn’t think much of the book, which was published in 1978, only a few years before his own: “We must, as a start, not delude ourselves with preposterous notions such as the straight Luddite position as outlined, for example, in Jerry Mander’s Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television.” Why is Mr. Mander a Luddite? He didn’t recommend getting rid of any other technology, and unlike the weavers who became the Luddites, the technology he wanted gone had put him to work, not out of work. And unlike Mr. Postman, Mr. Mander confronts the genial monster in the living room and bedroom head-on to the very end; Mr. Postman backpedals at the conclusion of Amusing Ourselves to Death, advising readers that it is how we watch TV and our newfound “awareness” of its shortcomings that will allow us to control it instead of it controlling us. In other words, he throws in the slingshot. Goliath wins.

Yet Mr. Postman has a point: I would’ve titled Mr. Mander’s book Why You Should Eliminate Television From Your Life Before It Eliminates You. While it’s true that short of a cosmic cataclysm we can’t eliminate TV altogether, I—and any other person—can eliminate it from our own lives. As Tolstoy said, “Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself.”

Mander gives each of his four arguments corresponding sections that examine his principal charges against TV: its mediation of experience, its colonization of experience, its harmful effects on humans, and its inherent biases. He makes some unsubstantiated or dubiously sourced claims. His sympathy with the hippie counterculture of the time and esoteric interests, such as the Hopi Indians, hinder his overall credibility and case. Despite all this, he also makes compelling observations.

Though flawed, the book found me, as books have a way of doing, at just the right moment with just the right overall message. It was my last step in my walking away from TV. Perhaps that I turned forty a month before the terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers (which I watched on TV from the West Coast) also created an urgency in me. Since at least the time I wrote my poem about what I’d like to do to my TV till our parting, I noticed that, in general, television had become nasty, crasser, subversive even. I sensed an agenda—political and cultural—that I now believe to be overt. I finally grew up.

Then a small incident occurred: my wife and I had ordered a movie (Spartan) from our cable company, but it wouldn’t play. My wife called about it, but the movie still wouldn’t play. When she called again, we agreed that she’d not only ask for a credit, but cancel our cable service.

Yet, as I’ve said, our TV remained in our living room for a few years more. It had been there so long it apparently refused to vacate the premises. Indeed, for nearly three-quarters of a century now the TV has become the modern hearth (sometimes directly over the gas fireplace). Now it’s a place to rest your web-weary bones and smartphone-clouded brain, where you can lose yourself in the rotating phantasm on the bigger screen. Home is where the TV is.

We had finally “cut the cord,” which has become a phenomenon of sorts in the past several years. But most of the cord cutters aren’t forsaking their televisions, just the cable TV providers. With the rise of Netflix and other online upstarts, viewers are abandoning cable TV after years of monopolistic price gouging; the newcomers provide more program and movie choices for less money (for now). Whether or not Big Tech eventually replaces the networks, the TV set is likely to remain on its living-room throne. Drive around the suburbs some night and see the garish glow in the windows from house to house. Or consider how some people will skip Thanksgiving turkey and trample a fellow shopper to snag a bargain on a TV, which is still the most prized item on Black Friday, that most cherished of American holiday traditions.

TV is now bigger than ever physically too; its screens are now gargantuan compared to the one I abandoned a dozen years ago. This is brought home to me whenever my wife and I visit her father for a week in Florida. At least some of the time we spend watching his fifty-five-inch flat-screen TV, which I think is a fairly typical size nowadays; interestingly, TV’s current mega screens were foreshadowed more than a half century ago in 1984 and Fahrenheit 451. His TV, like some, isn’t mounted on the wall like some monstrosity of non-art. He has two TVs, one in the living room and one in the bedroom, again fairly typical; a cousin of mine told me his son, a cop, has eleven TVs—one in each room of his house!

My father-in-law lives alone, an eighty-one-year-old widower. Which raises another defense of TV you sometimes hear: many elderly people—and the disabled of any age—consider television a sort of surrogate companion, a link to the world that has left them behind.

On a recent Sunday an elderly member of our church was talking to me and my wife after the service and she was amazed when my wife revealed, yet again, that we don’t have a TV. A widow for some years, she’s vibrant and likes to chat. And though she’s active in the church and all its doings, once back home she finds herself dreading the silence and turns to her TV: “It’s my best friend. I don’t like some of the stuff on TV, but I need somebody to talk to.” Even though she knows she’s not really talking to anybody, and nobody’s really talking to her. She’s far from alone in this sentiment. My mother, who outlived my father by thirty-one years, used to say the same thing.

Speaking of church, I suspect that some may see a TV-totaler as a puritan of sorts. It’s true that there are few things more “of the world,” which Christians aren’t supposed to be, than TV (despite the many televangelists, or partly because of them). But in my own case I stopped watching TV about five years before I became a born-again Christian, so religion had nothing to do with my final rejection of TV. Unbelievers with a moral bent, or who perhaps have better things to do, have undoubtedly done the same. In fact, I’d say that most, if not all, of the three hundred or so members of the church my wife and I attend not only own a TV but watch it daily, though selectively. As the elderly member of our church told me and my wife, “I don’t watch anything with guns or violence or anything like that.”

Others, no doubt, think TV abstainers are elitist. When I was a kid, in the working-class town I grew up in, one was wise to disguise any interest in or knowledge of books, even if you were a certified jock like I was. So, with TV, it’s junior high all over again. Peer pressure never grows old.

A few people seem curious when they hear of our escape from TV, as if the wild idea has crossed their minds, too. Sometimes they say they don’t watch much TV except for one genre—sports, or the news, or even the History Channel (apparently a favorite of older men). Sometimes, they blame it on their spouse, that he or she would never renounce what’s become a daily ritual. Then they click the remote and forget about the whole conversation.

I don’t know many of the celebrities I now see in the news. I don’t mind. It’s less mental clutter, let alone spiritual. As for TV news, which is inherently even more distorted than newspapers, I weaned myself off that long before I quit watching TV (though we’ve watched on the internet the presidential debates, inaugural speeches, and states-of-the-union addresses).

Still, I know I can never erase from my late middle-age brain all the commercial jingles and theme songs of the sixties and seventies, a surprising number of which I could probably still render in their entirety. Now viewers can skip TV ads by recording shows and fast-forwarding through them. When I was in high school, long before TiVo hit the market, I was forced to retreat to my upstairs bedroom during wrestling season; I had to make weight and couldn’t endure sitting downstairs in the living room and seeing all the food commercials on TV. These days, judging from our TV viewing at my father-in-law’s, commercials for pharmaceuticals are just as prevalent.

What about the fear of missing out (or FOMO as it’s now known) from not watching TV? On the contrary, I think of all that we missed out on when we watched TV: time, peace, conversation, reading, relaxation, writing, my wife painting. The only fear I have is the fear of falling back in. Every once in a great while I’ve watched some of the Dean Martin comedy roasts, which I watched as a teenager, along with a few skits from his comedy show. Nostalgia can be a dangerous indulgence. However, by now, the fear of a relapse is merely residual. When my wife and I stay in a hotel, after we come back to our room at night, we flip through the channels like newly arrived time travelers, but it’s not long before we have what feels like vertigo or the bends and switch it off. We like to sample what we’re not missing, just to reconfirm its banishment from our life and minds.

“If you want to watch TV,” our elderly fellow church member says to me and my wife with a laugh, “you can come over and watch it at my house.”

Instead, I think we’ll take her out for lunch at her favorite spot and we can all chat.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Jeff Plude has been a freelance writer for more than twenty years. He is a former daily newspaper reporter and editor, and he has written for the San Francisco Examiner (when it was owned by Hearst), Popular Woodworking, Adirondack Life, and other publications. His poetry has appeared in the Haight Ashbury Literary Journal.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast