Imagined Museum Exhibits in Israel

by Geoffrey Clarfield (December 2024)

Since I first set foot in the Land of Israel a few days after my 18th birthday, I have explored the land from the Golan Heights to the Red Sea and, in times past, spent many months in the Eastern Sinai desert as a young anthropologist. I have also visited and revisited many of Israel’s more than one hundred museums and each year a new one seems to pop up as if from nowhere, but once visited it becomes clear that it should have always been there.

And so, when as a young adult I served as a Museum Curator in a developing country for five years, now when I return to Israel, I look at its museums with a curator’s eye and imagine exhibits that I and many other millions of visitors to Israel’s museums would like to see.

Here are just a few of my imaginary exhibits.

1) Medieval Jewish Traders

If you travel from the port of Haifa up into the hills you will inevitably come across the Bahai Temple, a splendid neo-Islamic structure with magnificent gardens open to the public. Standing on the marble steps of the shrine of the founder of this religion you look out at the port and the endless horizon of the Mediterranean Sea.

The founder of the Bahai religion was a 19th century Persian religious reformer. I have read some of his mystical writings as well as studies of this very new member of the religions of the world, for he proclaimed that he too was a prophet within the Abrahamic tradition, and that Mohamed was not the last to prophesize.

I think it is true when scholars say that the problem of contemporary Islam is that unlike Western Christianity it has never had its own reformation. I also believe (and hope) that when personal liberty and democracy arise some time in the near future in the Islamic world, the Bahai faith will provide a face saving option for millions of Muslims who may no longer feel attracted to the Jihad of Islam and, who are looking for a framework for life in the 21st and 22nd century, one that allows them to embrace the history and culture of the Islamic faith without its Sharia law and commitment to holy war, for Bahai admires science and the equality of men and women.

Leaving these thoughts aside, I still find that when I look down at the bustling port of Haifa, I am amazed at the worldwide trading network that has been established by this “startup nation.” Modern Israel is a trading nation but somehow scholars and historians have forgotten that the Jewish people have had a maritime trading side to them going back to the time of King Solomon.

During the last thirty years, the State of Israel has gone through a change which has once again transformed the Jewish people and turned them into a society of export-based traders and travelers. Israeli businessmen and women can be found scattered over the face of the globe selling the products and expertise of the newly invigorated Israeli economy.

This includes newly established Jewish communities in those Gulf States such as Bahrain and Abu Dhabi who have finally recognized Israel. But contrary to popular opinion, Jews once lived in every one of these Moslem Arab countries, communities that were already ancient during the early Middle Ages.

Eight hundred years ago most of the Jewish people were scattered in communities that stretched from Spain to the Indian Ocean. But the people in these communities were neither isolated from each other or from what was going on in the wider world around them. In fact, they lived in close intellectual and commercial contact with one another and corresponded regularly.

This is because, unlike their Christian and Muslim neighbours, most male Jews at that time were literate. And, their entire way of life was based on trade, a trade that dealt with produce from as far away as northern Europe and which sometimes reached the distant Indonesian island of Sumatra.

We have a remarkably detailed picture of all aspects of the life of these Medieval Jewish Traders and their communities, due to the efforts of 20th century Israeli scholars such as the late S.D. Goitein whose multi volumed and detailed academic study, A Mediterranean Society─reads like an anthropologist’s field report from a preindustrial society.

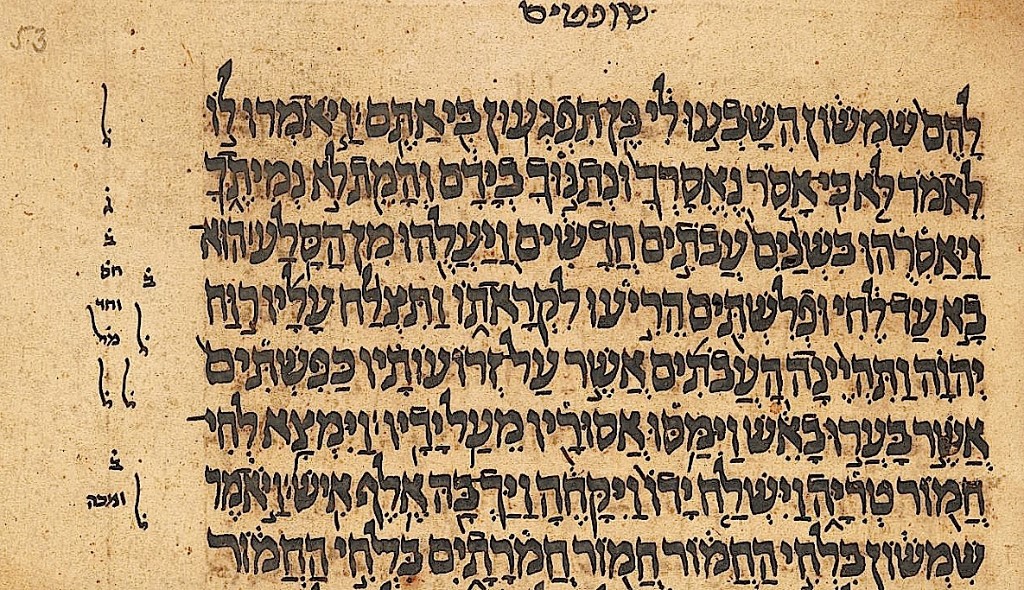

Within these volumes we read about all aspects of Jewish life, including the emotions of the small and the great. In the Cairo Genizah documents (the former archive of the Fustat Synagogue in Cairo, the Ben Ezra) upon which Goitein and his colleagues work is based, we have signed copies of Rabbi Moses Maimonides letter describing his grief after the death of his brother, a gem dealer, who lost his life at sea in the Indian Ocean on his way to Indonesia.

We also have a fragment of a letter from the poet Judah Halevi describing his newly written book, The Kuzari an intellectual defence of Judaism against the criticisms of Islamic and Christian clerics.

Hidden among the Genizah documents we also discover the oldest written precursor of the Yiddish language, a Medieval German romance written for a Jewish audience. Indeed, the Genizah is replete with descriptions of Jews from `Europe’ coming to live in Cairo and the Eastern Mediterranean thus showing that in those days, as in ours now, Jewish life was international.

Oddly enough, and again contrary to popular misconceptions, the Jews of that time lived in and among their Moslem and Christian neighbours, traded with them, did business together, formed partnerships and on occasion even consulted with one another on the etymology of sacred texts.

Goitein argues that Genizah documents demonstrate that the Jews of what we now call the high Middle Ages time lived in a period of free trade, with few customs regulations and under regimes who encouraged international commerce. This is confirmed by the British writer Bovill, in his book, The Golden Trade of the Moors, who also argues that during the height of the Crusades trade between the northern, mainly Christian and southern, mainly Moslem shores of the Mediterranean increased.

Compared to the fifty thousand surviving documents of the Muslim twelfth century the Cairo Genizah of the Ben Ezra Synagogue supplies us with over 250,000 documents that describe all aspects of medieval Jewish daily life. They provide us with what can only be described as an `ethnography of the Jewish communities of the 12th century.’ The Jews of this time were brave and enterprising traders who regularly travelled the sea routes from the coast of Morocco to the Horn of Africa and the shores of India.

Some people have called today’s Israeli entrepreneurs, `The Phoenicians of the Modern World,’ but they are merely doing what was done by their ancestors many centuries ago, all of which is so beautifully described in the documents from the Cairo Genizah.

An exhibit that teaches this to every visitor to Israel would focus on the material world of the Jews of the Genizah during the 12th century, a time which parallels the early Crusades. Through presentations of original and facsimile Genizah documents, photos, videos, artifacts and exhibits of the spices that were traded, this exhibit will evoke the world material described in the Genizah.

A Museum Catalogue would accompany the exhibit and could function as a guide to the exhibit. It would also serve as a popular condensation or summary of Genizah research that will make it more accessible to the wider public.

2) Kinnor David -The Quest for David’s Harp

In the archaeological excavations carried out in the royal tombs of Ur, in Mesopotamia, beautiful ancient harps, covered with gold leaf have been brought to light after having been buried for thousands of years.

The shape of these harps, which are technically `lyres,’ are the same as those found in Ancient Israel and Greece and which are commemorated on the 25 Agorot piece of the State of Israel. Indeed, in Jewish tradition we picture King David, alone in his palace, singing his newly written psalms while playing on his `kinnor,’ which in fact was a variation of the ancient near eastern lyre.

Unfortunately, although archaeologists have found buried lyres and pictures of their use in wall paintings, in carvings and on the sides of pottery, we have very little idea of what they sounded like. We can see the instruments, but we cannot hear the music. For by the end of the period of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages the lyre was no longer heard in the cities and courtyards of the near east. About a thousand years ago evidence of its use disappears from the archaeological record.

However there is good ethnographic evidence showing that after the kinnor died out along the East/West trade routes of the near east, it diffused south down the Rift Valley and along the Nile River basin.

During the last few centuries, as European explorers began their search for the source of the Nile, they entered the Christian Kingdoms of Highland Ethiopia and moved among the tribes of East Africa. There they found variations of the ancient Israelite lyre still in use. It had diffused all the way to the tribes who inhabit the source of the White Nile, around what is now called Lake Victoria.

In fact, the lyre is still found in various forms among the villagers of the Red Sea, in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the Sudan as well as in Uganda and Kenya. It is found in several forms in highland Ethiopia where wandering bards sing while playing the smaller versions of the instrument.

Larger versions are documented as far back as the late seventeen hundreds in the journals of James Bruce of Kinnaird, the Scottish explorer who lived among the Royal Court of the highland Ethiopians. The lyre has also been in use among the Beta Israel-the last Jews of Ethiopia.

On my last trip to Ethiopia, I spoke to experts at Addis Ababa University who showed me the lyres in their storage units and who explained that composers speaking Ethiopian Semitic languages still sing Davidic Psalms while they perform on this ancient instrument.

This exhibit could document the Harp of David in its many variations and show its probable diffusion route south along the Nile River basin during the last two thousand years. We could exhibit the instruments themselves and provides photos, artifacts and films of lyre players from the various cultures who still use it as a musical instrument.

We could ask the Cultural Attaches of Egypt, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Kenya to help us bring to Israel the musicians who still use this instrument for a series of performances to be held at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem or any other, such as the Maritime Museum in Haifa. This would show the variety of musics which have flourished from the adoption of this ancient Israelite and Near Eastern Lyre.

3) Israelites and Canaanites

Almost every Jew, and most Bible readers for that matter, sympathize with the Israelites and see the Canaanites as sophisticated, hierarchical, unfair, polytheistic and at worse, worshippers of Moloch and rooted to the `Baal’ or idol of their hill or city.

In the Bible the Israelites are portrayed as the opposite of the Canaanites, rustic, monotheistic, worshippers of the one God and proto universalists. Nonetheless, every Bible scholar knows that the relationship between Canaanite and Israelite was longstanding and complex.

We know for example that the language that the Canaanites and the Israelites spoke were mutually intelligible. Any difference was no more than that which occurs today among neighbouring dialects of modern Spanish or Italian. The model for the first Temple was based on a Canaanite temple prototype. King David traced his priestly legitimacy through Melchizedek to a Canaanite origin.

The Psalms, once thought to have crystallized in the fifth century BC, may have their origins in the late Bronze age, among the Canaanite texts found in Ras Shamra. From reading the prophets it is known that Israelites often worshiped at the shrines of the Canaanites, yet no doubt many Canaanites also joined the faith of Israel.

There is a controversial academic theory that suggests that the Israelites themselves were Canaanites, who, as part of a peasant revolt, differentiated their religion and culture from their immediate past and made common cause with the descendants of, ‘wandering Arameans’ and perhaps newly returned exiles from Egypt.

Most laymen and scholars alike find this theory hard to accept. A poll in the Biblical Archaeological Review points out that only a small number of interested professionals and laymen accept this theory. Perhaps this is because it is hard to realize how much the Canaanites and Israelites shared a common culture.

The goal of this exhibit then is to demonstrate the similarities and differences of Canaanites and Israelites. It will use models, artifacts, photos and exhibits on domestic life, to show that these two cultures shared much although, in the end they diverged dramatically.

It is fitting that such an exhibit could be sponsored by the Maritime Museum of Israel because the final conflict between the followers of Baal and those of the one God took place in the Carmel hills, just above the Maritime Museum. Today, Jewish, Christian, Muslim and Druse, all followers of Elijah (El Khadr, in Arabic) still sacrifice sheep in honour of him in the shrine of Eliyahu’s cave, just down the road from the Museum. Such a ritual site is an ideal topic for a related documentary film.

Did the Canaanites really worship a God named Baal? Or was there a Baal worshiped in every hill and town that the gifted urbane Canaanites built across the land of Israel, Lebanon and what is today Syria. Stay tuned.

4) Chanukah, Judaism and Hellenism – Conflict and Compromise

The greatest cultural and political challenge that ever faced the Jewish People has been that of Hellenism. It was brought by polytheistic Greeks who not only traded with Israel across the Eastern Mediterranean but who settled in large numbers in the Land of Israel and who, like the ancient Jews, believed in the universality of their way of life and who felt that all men and women should adopt their culture.

Until the rise of European secular democracy (whose roots are both Jewish and Hellenistic) no other culture has ever had such a dramatic influence on how Jews have conceived of their relationship to God, with their fellow Jews, with non-Jews and with the world around them. Indeed, the Festival of Chanukah is still celebrated by Jews around the world to commemorate their survival against some of the more brutal aspects of Hellenistic despots.

Nonetheless, the influence of Greek culture on the Jews was and remains profound. Greek became the language of many Jews. The Bible was translated into Greek. Greek philosophy was incorporated into Jewish theological thought by Alexandrian Jews like Philo and Greek forms of art, architecture and technology changed the way that Jews lived their daily life.

One could also argue that it was the reaction against Greek culture that stimulated the collection of the oral law, the rise of the Rabbinic movement and the compilation of the Talmud as barriers to what was thought of as essentially a relativistic and immoral culture.

At the same time, many compromise formations between Hellenizers and non Hellenizers characterized Jewish society from the Maccabees to the final wars of the Jews against their Hellenised Roman overlords and who themselves were later conquered from within by a new variation of the Jewish/Hellenic matrix-Christianity. And we should seriously ponder the meaning of the many religiously based political assassinations of the Sicarii described so well in Josephus, The Jewish War, and which were common in those days.

In modern Israel more than in any other democratic country with roots in the Biblical tradition, the tension between the Hellenistic culture brought by the seafaring Greeks and the desert monotheism of the Jews is still reflected in contemporary tensions between religious, secular and `traditionalist’ factions within the State.

An exhibit on this topic would gain relevance and attract a large audience through a series of popular lectures by Israeli experts to be delivered at an Israeli Museum. The speakers would structure their talks to the public by comparing modern life in Israel with that of the Hellenistic period. Topics would include the role of women, social inequality, multilingualism, attitudes towards sex and the family, the role of philosophy in society, class, wealth and personal freedom.

An exhibit of this kind is more than an evocation of the past, as it is reflected in two living archaeological sites, the Western Wall of Jerusalem which is part of the Rabbinic tradition that goes back to the teachers of the law during the second temple and the archaeological site of Herod’s Caesaria which expressed all and every aspect of Hellenistic culture in both its ancient and modern forms with its spas, boutiques and fancy restaurants.

Such an exhibit could be illustrated with beautiful photos of archaeological remains and the like. It is an invitation for modern Israelis and sympathetic visitors to look into the mirror of history and once again contemplate the tensions and paradoxes of building a society based on the pursuit of personal happiness, reason and faith, against those who believe they have a monopoly on the interpretation of revelation.

5) Common Proverbs – Proverbs in Common

The Hebrew and Arabic languages are rich in proverbs. Indeed, one Biblical book goes by that name, which only goes to emphasize how important proverbs are among near eastern peoples. Yet it is not well known that many traditional Hebrew and Arabic proverbs descend from a group of proverbial expressions that coalesced in the Aramaic language around the fifth century B.C.

With the rise of Islam in the Near East and North Africa, and with the later eclipse of the Aramaic language by Arabic, many of these proverbs were translated into Arabic. Subsequent scholars have often thought of them as part of the Islamic heritage of the Arabic speaking peoples of the Mediterranean and the Near East. In fact, these proverbs form part of the common near eastern culture and language that makes the near east one kind of civilization, despite its great diversity.

The goal of this exhibit is to display a series of black and white photographs of daily life taken by the author during a year’s residence in Morocco in 1976, and which illustrate the context of a large number of these common proverbs.

Below each photo there will be the Hebrew and Arabic version of the proverb along with an English and French translation. The exhibit will be accompanied by a brochure showing the history and relations of these proverbial collections.

I must stop now. I could continue-an exhibit on Angelology-Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Yazidi, an exhibit on the history of the Ark of the Covenant and its disappearance, an exhibit on the Biblical influence on the American Constitution, an exhibit on a theme in British culture where that nation once thought they were direct descendants of Israelites or, one on Sir Isaac Newton’s massive and private musings on the Temple of Jerusalem whose personal papers on that matter are archived in this same city.

The list goes on and I encourage others to do make their own. The Land of Israel has many stories to tell, and these are just a few that I hope to bring to light, one day.

Table of Contents

Geoffrey Clarfield is an anthropologist at large. For twenty years he lived in, worked among and explored the cultures and societies of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. As a development anthropologist he has worked for the following clients: the UN, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Norwegian, Canadian, Italian, Swiss and Kenyan governments as well international NGOs. His essays largely focus on the translation of cultures.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast