by Jeffrey Burghauser (December 2024)

In his review of an 1813 edition of James Boswell’s The Life of Samuel Johnson, Lord Macauley writes: “[Poets] were as untamable, as much wedded to their desolate freedom, as the wild ass. […] If a sum was bestowed on the wretched adventurer, such as, properly husbanded, might have supplied him for six months, it was instantly spent in strange freaks[1] of sensuality, and before forty-eight hours had elapsed, the poet was again pestering all his acquaintances for twopence to get a plate of shin [i.e. “shank”] of beef at a subterraneous cook-shop.”

By this definition, America has become quite poetical of late. There’s no phrase better than “desolate freedom” to describe the afflatus behind “drag queen story hour,” the nihilistic worship of Hamas and Hezbollah, and the barbarism that filled our streets during the George Floyd Affair. What’s a poet to do now that libertinism has become monopolized by the “mainstream”? What’s the would-be rebel to do when bank commercials promote sodomy, the Church of England goes agnostic, and museum curators express hatred of the very traditions they’re supposed to be serving?

If propriety is now countercultural, poet Michael Shindler is developing into our own Abbie Hoffman.

***

In the invocation to Paradise Lost, John Milton readies us for the singular magnitude of his project, petitioning God Himself for inspiration: “I thence / Invoke Thy aid to my adventurous song, / That with no middle flight intends to soar / Above the Aonian mount, while it pursues / Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme.” Milton sets a high bar; we should expect nothing less from this most manly of poets.

But the “middle flight” is nothing to be sniffed at. Indeed, the “middle flight” represents the Great Tradition’s core. To pursue “[t]hings unattempted yet in prose or rhyme” requires that you inhabit a culture in which many things are attempted (successfully) in prose and rhyme. To reduce excellence to mere excellence, you require a cultural atmosphere in which there’s quite a lot of excellence about. For this reason, we’re unlikely to encounter Miltonic voices nowadays. It’s an impossible goal. Far more urgent that we rebuild a culture of poetry characterized by gravity and superior craft—that we produce poets capable of attaining that “middle flight.”

In Fret Not, Michael Shindler proves himself just such a poet. Its contents seem to inhabit two categories: (a) tight, short lyrics that gleam like Fabergé eggs, and (b) longer pieces that have the slow, melancholy spaciousness of a Chopin nocturne.

In the first category, the cleanliness of the language is often counterpoised against the form’s gentle irregularity. See, for instance, “Pan is in the Wood”:

| Pan is in the wood | |

| And she heard him, | |

| Though he is dead. | |

| There’s evil, good | |

| 5. | And something grim |

| Life leaves unsaid | |

| In the dead god’s hymn. |

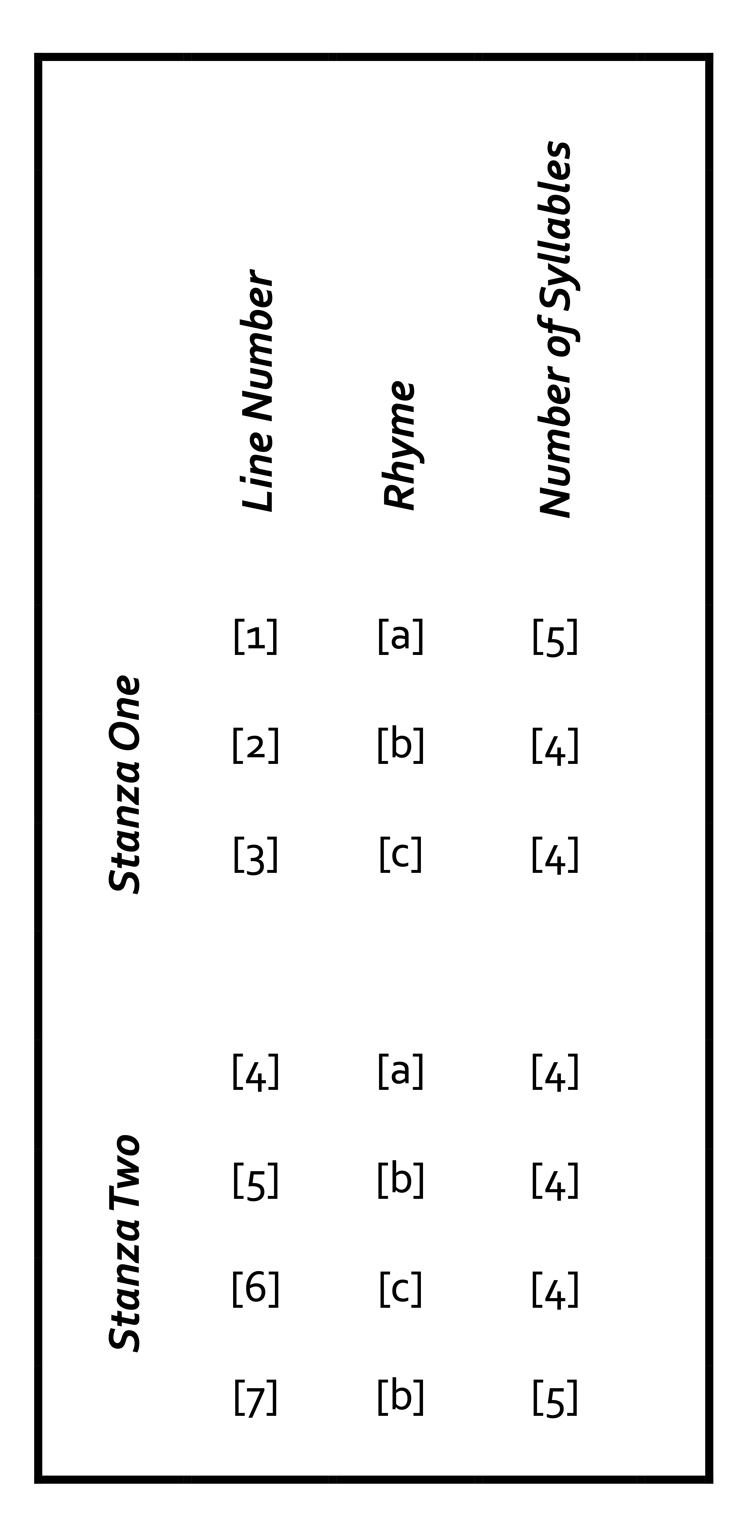

Excarnated, the poem’s structure looks like this:

The structure recalls the sestet of an Italian sonnet, where the rhyme scheme commonly goes ABCABC. The second stanza, however, has a coda connecting that stanza to the one preceding it, interrupting any sense we might have developed of “moving forward” through the piece. If you have three stanzas with a coda after the third, two things are clear: (a) an overarching pattern exists, and (b) the coda fruitfully undermines that pattern. But if you have only two stanzas, it isn’t quite obvious that any general pattern exists at all, thereby producing doubt as to the coda’s “character.” Is Shindler’s seventh line an appendage to something, or is it integral?

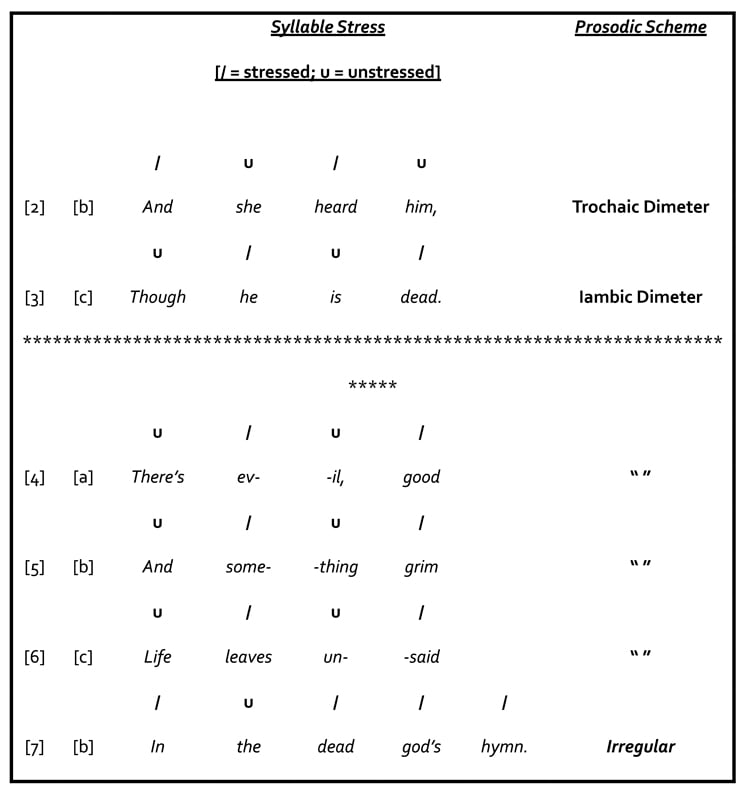

Our pleasing disorientation is buttressed by the prosody. The opening line (“Pan is in the wood”) isn’t just a syllable longer than all but the final line; it’s also the only line written in even, muscular trochaic feet. We expect it to be followed by a similar line. What we get, however, is this:

But even where there’s prosodic regularity, nothing equals the rhythmic bicep-flex of that opening line.

Shindler punctuates manly directness with thoughtful obscurity. It reminds me of Emily Dickinson or Robert Creeley. It’s almost as if a single shaft of light has penetrated a well-appointed room, illuminating a single edge here, a single contour there, encouraging us to deduce what objects populate the remaining fields of perfect darkness.

“Pan is in the Wood” (typically for Shindler) contains moments of deft, sinewy negation: “Pan is in the wood / And she heard him, / Though he is dead.” By comparison, when Emily Dickinson’s narrator hitches a ride with Death, the narrator reports that “The carriage held but just ourselves / And Immortality.” In “Anger,” Robert Creeley’s narrator describes a metaphorical pit, “which he recognizes, / familiar, sees / the use in, a hole // for anger and / fills it / with himself, // yet watches on / the edge of it[.]” The narrator manages to be in two places at once.

These irregularities and discontinuities produce a pleasant frisson. In “A Purple,” Shindler writes: “A purple abandoned in the dust / Of an impressionist painting; / A music fit for fame and fainting; / Wrought iron meant to rust.” Samuel Johnson defined wit as “a combination of dissimilar images, or discovery of occult resemblances in things apparently unlike.” I can’t think of a better example than Shindler’s reference to “[a] music fit for fame and fainting.”

Speaking of Impressionist painting, Cézanne’s The Kiss of the Muse (1860) has long moved me, despite its slightly overdone, gauzy romanticism. It depicts the archetypal poet sitting at his desk beneath a dark garret’s sloped ceiling. He swoons limply while a glowing, angelic figure arches over him from behind, kissing his brow. We can tell from the poet’s face that his torpid melancholy is being somehow interrupted, though he doesn’t know by what. We do, though. And we wonder about the poem he’s nearly prepared to write.

Whatever he ends up with, it’s unlikely to be better than the exquisite lyrics collected in Shindler’s new book—a book that could plausibly have been titled Shindler’s Kissed.

[1] “Freak” here refers not to post-op transexuals; rather, it means “caprice,” which John Milton uses figuratively in his description of “[t]he tufted crow-toe, and pale jessamine, / The white pink, and the pansy freaked with jet…”

Table of Contents

Jeffrey Burghauser is a teacher in Columbus, Ohio. He was educated at SUNY-Buffalo and the University of Leeds. He currently studies the five-string banjo with a focus on pre-WWII picking styles. A former artist-in-residence at the Arad Arts Project (Israel), his poems have appeared (or are forthcoming) in Appalachian Journal, Fearsome Critters, Iceview, Lehrhaus, and New English Review. Jeffrey’s book-length collections are available on Amazon, and his website is www.jeffreyburghauser.com.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

2 Responses

Excellent review. I shall try it.

As I have advised the author previously, there is but one banjo picking style worth learning: Claw hammer.

Good review, as always