In the Trenches with Revenge

by Robert Lewis (August 2021)

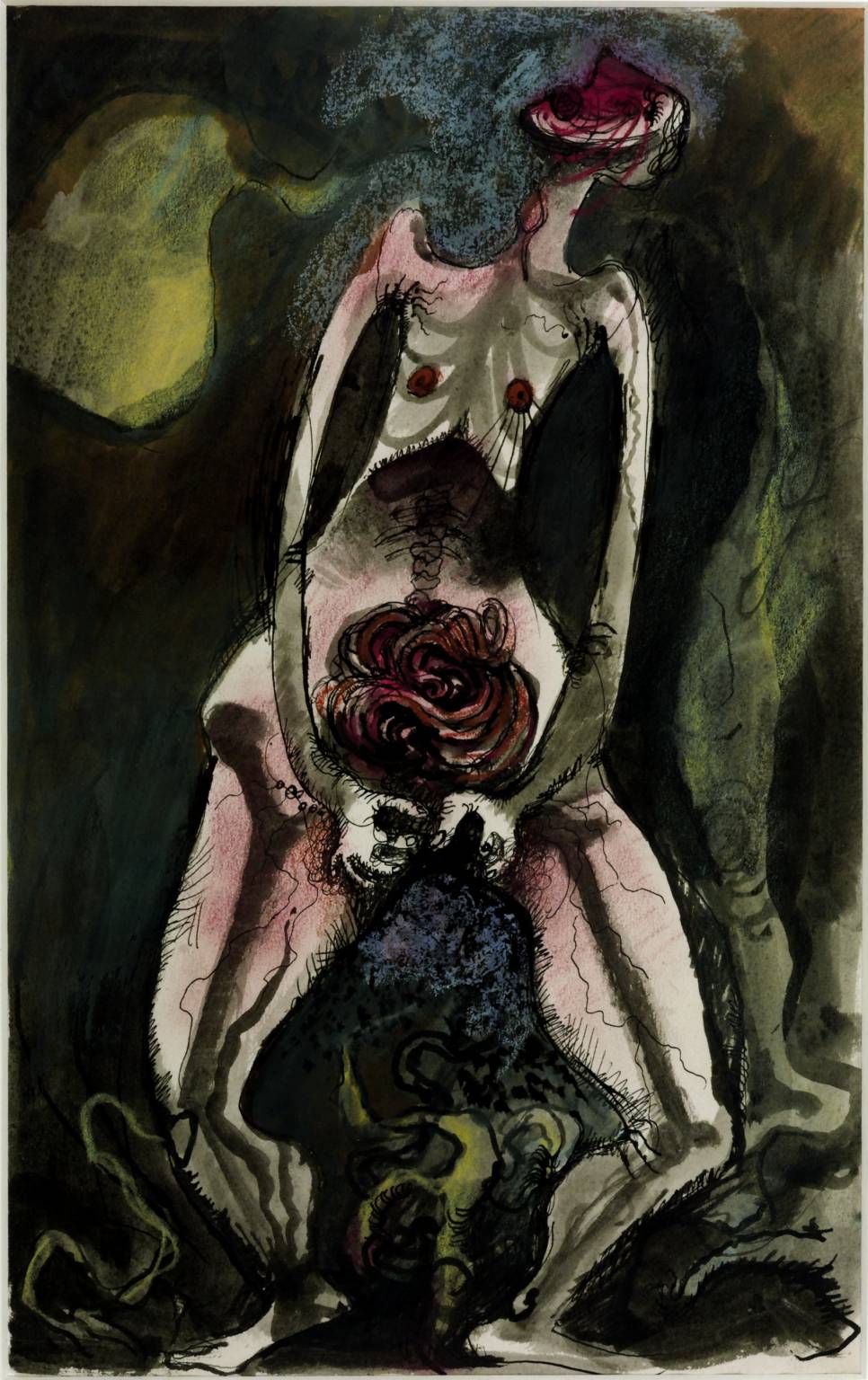

Communication of Hate, Keith Vaughan, 1943

While seeking revenge, dig two graves—one for yourself. —Douglas Horton

The best revenge is to be unlike him who performed the injury.—Marcus Aurelius

Decidedly unimpressed with the prerogatives of human nature, the sages, when reviewing the long list of candidates for the exclusive Seven Deadly Sins club, decided that revenge—as a manifestation of Wrath (anger, hatred)—should be included.

Thus, the laws of most lands ask that we refrain from taking revenge because, pace the logical positivists, the passions are to be mistrusted, and deliberately causing serious if not fatal injury to someone in the name of revenge reflects poorly on the individual and the values of the society he represents. At the same time, we feel there is a natural kinship between revenge and justice as it concerns rules of conduct and their application. Ralph Waldo Emerson writes that the innate existence of the retributory faculty predicts the imperfect world we inhabit, as the wings of a bird in the egg presuppose air. Properly channeled, revenge motivates the individual and, by extension, society to address (correct) unacceptable behaviour. Revenge is the passionate implementation of society’s dispassionate laws.

When an angry man turns on the drunk driver who has killed his child, or when the masses turn on their tyrannical leaders (Ceausescu, Saddam, Gaddafi), we usually don’t debate the legality of it but conclude that the brutes got what they deserved, that justice was served. We note that the courts will exonerate the man who kills the person caught red-handed strangling his wife, but will punish him for taking the law into his own hands if he kills the guilty party at a later date. Such are the unreasonable if not prodigious demands imposed on human nature by the law and its categorical rejection of retributive justice.

Prior to the formal establishment of law, revenge served as an invaluable deterrent and played a major role in shaping a society’s values and regulating its conduct.

When our primal predecessors lived in tribes, those who were—by nature—short-changed on revenge would soon find themselves overwhelmed by an unrevenged enemy that, with impunity, took what it needed and wanted— when it wanted. Since the enemy survived and propagated its own, wrongdoing ended up doing right.

And yet from Confucius to Ghandi—“an eye for an eye only ends up making the whole world blind”—our wisest have counseled against revenge, though conceding that the feeling is perfectly natural. Today, for the sake of the greater society, we are asked to sublimate the instinct by devolving the responsibility of taking revenge to our more responsible (dispassionate) institutions of justice. But if the much adored and copiously downloaded revenge-film genre is any indication, we do so reluctantly, contre nature.

Brain-imaging scans show that when we anticipate eating a favourite food or contemplating revenge, the dorsal striatum part of the brain is rewarded; that same area lights up following nicotine and cocaine consumption. That ‘revenge feels good’ is not merely a figure of speech but a quantifiable physiological response to unacceptable personal affront.

Revenge is a dish best served cold. However, when acted upon, it is seldom as sweet as anticipated because it does not undo the original offense that triggered it, which makes it, as a practical consideration, more of an adjunct of law and order than a lust to be satisfied.

In Daniel Grou’s gruesome film, The 7 Days of Retaliation, the protagonist’s (Dr. Hamel) 8-year-old daughter has been brutally raped and murdered. The doctor finds himself deeply unsatisfied with the pace of justice and decides to take matters into his own hands. He arranges to kidnap the murderer—whose DNA leaves no doubt as to his guilt—and in the spirit of retribution announces to the authorities that he’s going to torture and murder the pervert and then give himself up a week later, on the day his daughter would have turned nine.

The cabin where the revenge tryst takes place is arranged to resemble a slaughterhouse, the lighting is grim save for Caravaggio-like flames of interior light falling on the naked squirming pedophile’s morgue-white body whose cries for mercy go unheeded. If revenge porn is your thing, this film presses all the right buttons. The blood reckoning is off the charts and I couldn’t wait for the good doctor to surgically remove the murderer’s penis without the benefit of an anaesthestic. Wish granted. And when the avenger finally turns himself over to the authorities, without having, as promised, killed his daughter’s killer, we want the laws of the land to acquit—which speaks to the ambiguity unleashed by the emotion of revenge: on the one hand it’s barbaric, on the other hand it’s natural and right.

Playing both hands with impartial conviction, the film forces the viewer to confront his own appetite for revenge—and then the utility of its operations when left unhinged. The film asks: since revenge is deeply embedded in the human psyche (it cannot be talked away) what is the individual to do when the law fails to extinguish its fires?

Reduced to its lowest common denominator, revenge is the unapologetic (demi)urge to eliminate the genes of the person who has committed an unpardonable crime not only against an individual, but society: its core beliefs, its organizing principles, its present and future face. Revenge, with nature’s blessings, identifies, condemns and executes in order to extirpate toxic genes from the body politic. As an enforcement tool, it shapes and affirms the ethical codes upon which every stable society depends.

The pedophile who has raped and murdered has not only broken the law, he has broken and violated a sacred trust. For the sake and vigour of the gene pool and the ideals and hopes it carries and transmits from one generation to the next, not only do we desire revenge, but upon calm reflection, we may very well deem the taking of revenge a duty to both self and society, and to ignore that imperial ‘calling of conscience’ is to risk leaving ourselves civilizationally wracked with discontent—the Freudian formula for neurosis. The film makes the argument that whatever revenge is, it should not be one of the Seven Deadly Sins.

Is it fair or reasonable for society to expect someone whose family has been butchered to be satisfied with a lengthy incarceration, which if long enough is tantamount to eliminating the offender’s genes?

Time does not heal ‘all’ wounds nor does it heal uniformly In Canada, a young man who murders at 18 may find himself free before the age of 40, and potentially capable of passing on his defective genes and/or defective behavioural disposition to his offspring, which raises the question of capital punishment, which raises the even greater question of intractable errors in the judicial system, which is why most civilized countries explicitly outlaw the death penalty. But even in the best case scenario, we know that the maximum punishment prescribed by the courts often falls short of the injured party’s understanding of what constitutes just punishment. Which begs the question: should our laws concerning crime and punishment be tweaked to be better aligned with human nature?

If we decide that it is barbaric to execute the pedophile who has raped and murdered, should the law, at a very minimum, grant the aggrieved a say in the punishment—the manner in which the felon will pass his incarceration, at least until he either deceases in prison or is set free?

Is it reasonable to suggest that as long as the pedophile-murderer lives, he should be obliged to serve the family he has violated; meaning during and after his sentence has been served, all fruits of his life’s endeavours, however paltry, should go to the family? Should the surviving family members, in addition to the prison sentence, be offered the option of prescribing either castration or lobotomy? Of course the latter precludes repentance and rehabilitation. More generally, what concessions, if any, should be made to the cause and effect engendered by revenge that will do a society proud before the nations of the world?

The more thought we offer to revenge and all that it implies, the thornier the issue becomes. If we are to get the better of the reflex, that is learn how to more productively work with it, we will have to stand unflinching before the mirror and shake hands not only with the executioner but also the person who has a score to settle and a broken heart to mend. Only then will we be in a position to better understand our conflicted nature and the kind of freedom we are seeking.

__________________________________

Robert Lewis was born in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. He has been publislhed in The Spectator. He is also a guitarist who composes in the Alt-Classical style. You can listen here.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast