by Pedro Blas González (October 2023)

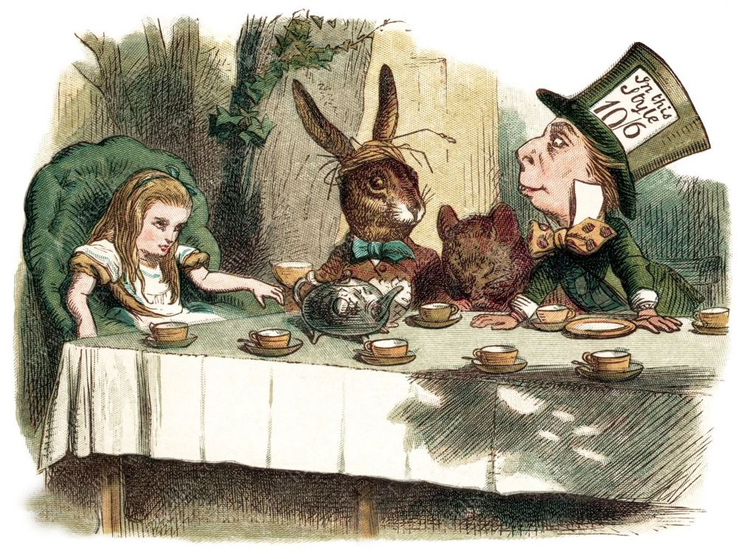

Illustrations by John Tenniel, 1865

“I can’t remember things before they happen.”

“It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards,” the Queen remarked.

————————Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking-Glass

What a pleasant surprise it is to re-read Lewis Carroll.

Having known Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass since I was a child makes reading these works as an adult doubly enjoyable in their ability to predict the mendacious world of postmodernity. Children only know the popular movie-like qualities of those marvelous books.

Carroll is not an easy read. Yes, the works are playful, taking great liberties with language, double entendres, and suggesting a life-as-dream pathos. Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass demand that readers come up to their level and figure out the narrative that the writer conceived. Like Aesop’s Fables and other wisdom literature, the wisdom contained in Carroll’s work is learned and assimilated throughout a lifetime. This is one reason why reading these works as adults is so fruitful. Carroll’s books live on, continually engaging discerning readers. Yet ours is anything but a discerning age.

I can’t imagine children today—who, from an early age, have their innocence and sense of awe and wonder corrupted by the cancer of our computer-digital age—have the vaguest clue as to what Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass are about, what life-affirming meaning these works convey.

I can’t imagine children today—who, from an early age, have their innocence and sense of awe and wonder corrupted by the cancer of our computer-digital age—have the vaguest clue as to what Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass are about, what life-affirming meaning these works convey.

A dumbed down, racialized and sexualized age; in short, a debauched, decadent time destroys the imagination of adults first, then the adults corrupt the children ad nauseam. One cannot pass on to others what one does not have.

The striking thing about Carroll is his awareness of the passage of time. Life, Carroll suggests throughout his writing, has a dream-quality to it that only those who are awake can understand. Irony and paradox are both staples of Carroll’s writing.

Life is serious business, Carroll suggests. Ironically, only people with imagination who retain their innocence can understand this. Carroll jabs at the reader and entices them to come to his corner. In this regard, he belongs in the company of thinkers and writers like Calderon de la Barca and Jorge Luis Borges, to mention only a few.

Once lost in the forest of her dreams, Alice attempts to understand herself, in what is a maze of aberrant and bizarre experiences. Her meeting with morally corrupt, dysfunctional beings is a threat to her sanity and wellbeing. Granted, some of the entities she encounters are harmless buffoons.

The young girl wills herself to refrain from joining the club-of-aberrant-delights that she is presented with. This is a major take-away from Carroll’s now classic works. Hers is a solitary trek, with only her wise counsel to guide her.

Alice does not need a ‘life-coach’ to hold her hand.

The dream-quality of life in Carroll’s work cannot be grasped by the moral, spiritual, cultural, and intellectual dark age that is postmodernity. Let us not forget that postmodernity is predicated on the nihilistic notions that nothing means anything, that there are no objective standards because everything is relative, and that objective narratives must be annihilated. For this and a slew of other relevant reasons, postmodernism cannot even pretend to understand works of the Western Canon, including Lewis Carroll.

Postmodernism attempts to break all ties with man’s past, culture, literature and morals. Taking a page from the Bolshevik book-burning, re-writing of history, postmodernism is fueled by resentment and destruction; nihilism feeding on itself.

Postmodernism attempts to break all ties with man’s past, culture, literature and morals. Taking a page from the Bolshevik book-burning, re-writing of history, postmodernism is fueled by resentment and destruction; nihilism feeding on itself.

Given postmodernism’s attempt to annihilate (deconstruct) human achievement and civilization, it consequently disqualifies itself from judging and critiquing the past.

We mustn’t forget that the freakish and aberrant characters that Alice comes across are not the rule, rather the exception. She comes to understand this in due time, as she battles their adverse notion of reality. Alice turns to common sense and reason to deliver her out of the maze of mendacities that she must make sense of.

One of many points that Carroll makes in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass is that even at the callow age of twelve, Alice can decipher truth from appearance. Good for her.

An intellectually lazy and ideologically postmodern ‘reading’ of Carroll’s works by critics today finds it necessary to substitute the rule with the exception, thus normalizing aberration, vulgarity, and dysfunctionality. Luckily, Alice knows better.

The point is not that Alice discovers that freaks exist, but rather that she does not have to emulate their vulgarity. Alice is assaulted with nonsense and dysfunction throughout her adventures.

In one way or other, Alice’s innocence and sense of wonder become the target of the freaks she encounters. Consider the vitriol of a rose in chapter II (‘The Garden of live Flowers’) of Through the Looking-Glass: “It’s my opinion that you never think at all,” the Rose said, in a rather severe tone.” Then, a violet chimed in, eagerly: “I never saw anybody that looked stupider,” a violet said, so suddenly, that Alice quite jumped; for it hadn’t spoken before.” Alice is defended by the Tiger-lily, who scolds the other envious flowers: “Hold your tongue!” cried the Tiger-lily. “As if you ever saw anybody! You keep your head under the leaves, and snore away there, till you know no more what’s going on in the world, than if you were a bud!”

Consider a few poignant lines—not the entire beautiful poem—that appears at the end of Through the Looking-Glass:

Long has paled that sunny sky:

Echoes fade and memories die:

Autumn frosts have slain July.

Now, let us consider the beauty of those lines in our age of noise, the tyrannous media, television, Internet, and the innocence-annihilating meat grinder that is social media, where one only encounters echoes and mockery of human reality. But, echoes of what? For there to be music there must be melody, harmony, and form, and postmodernity only leaves us with dissolution of values, mere sound and fury.

Now, let us consider the beauty of those lines in our age of noise, the tyrannous media, television, Internet, and the innocence-annihilating meat grinder that is social media, where one only encounters echoes and mockery of human reality. But, echoes of what? For there to be music there must be melody, harmony, and form, and postmodernity only leaves us with dissolution of values, mere sound and fury.

To compound the dead-end that is postmodernity, our echoes never make it past the stage of being more than cacophony – the aggressive clang of unprecedented idiocy and mendacity. A consequence of this is that the protagonists of our age are fifth-tier supporting actors, people who have not earned the right to critique the past. What can remain memorable in an age that is saturated with throw-away-life and culture?

Alice’s cultivation of memories in Carroll’s dream-sense becomes an instructive part of the young girl’s life.

The poem ends with the lines:

Ever drifting down the stream—

Lingering in the golden gleam—

Life, what is it but a dream?

The beauty of the aforementioned lines is nullified by the violent, here-and-now quality of our nihilistic age. Unable to comprehend the wisdom and depth of thought of writers like Carroll is not only damaging to the human psyche, but also culturally embarrassing.

The opening poem to Sylvie and Bruno equally shocks our postmodern lack of sensibility:

Is all our Life, then, but a dream

Seen faintly in the golden gleam

Athwart Times dark resistless stream?

Bowed to the earth with bitter woe,

Or laughing at some raree-show,

We flutter idly to and fro.

Man’s little Day in haste we spend,

And, from its merry noontide, send

No glance to meet the silent end.

What more can be said?

Table of Contents

Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy in Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay, Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man, Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity. He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998). His most recent book is Philosophical Perspective on Cinema.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

2 Responses

What a well written essay, Dr. Gonzalez. So real, so heart-felt. Beautiful description of being alive when the world tries to erase the differences between good and evil and truth and false.

No, this must not stand.!

Wonderfully re-examined. Thank you very much