by Kenneth Francis (November 2018)

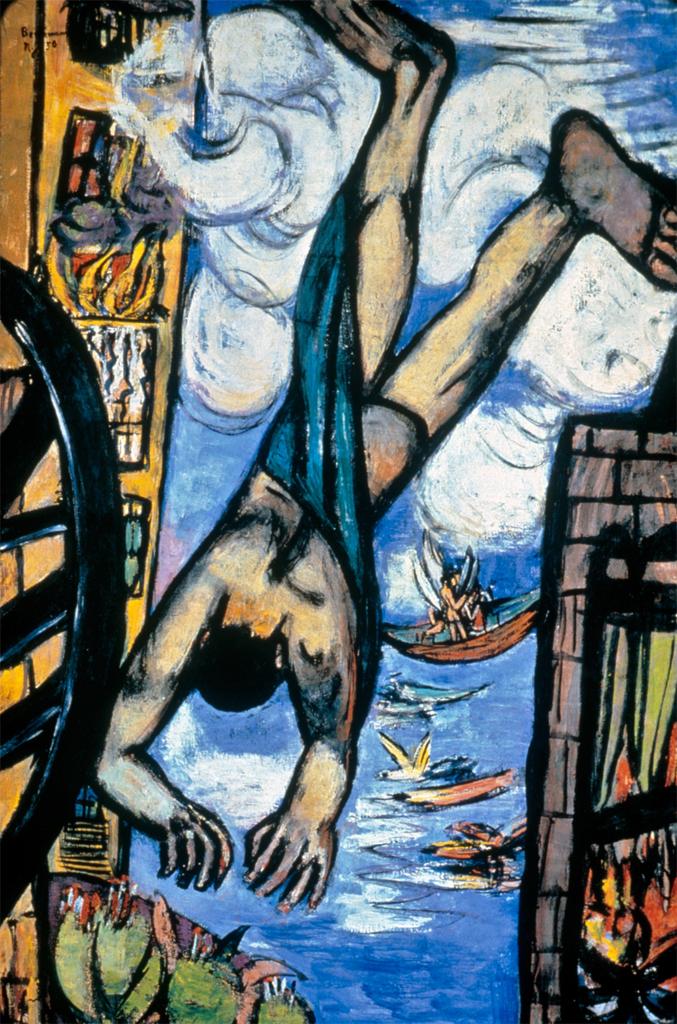

Falling Man, Max Beckmann, 1950

This month sees the 55th anniversary (November 22, 1963) of the death of three of the world’s highly rated, influential idealists: writers Aldous Huxley, C.S. Lewis and American president, John F. Kennedy. This coincidental triune bereavement kept the obituary writers busy during that fateful day, but Kennedy’s death would eventually get top billing, his bloody assassination eclipsing Lewis and Huxley in terms of human-interest appeal.

What’s intriguing about these three men is their deep interest in the fate of humankind: Kennedy was suspicious of shadowy figures negatively interfering in world events; Lewis was concerned about the threat of Secularism and disbelief in God; while Huxley wrote about the future of a Brave New World. This dystopian novel, published in 1932, is set in a futuristic New World Order (based in London), whose population is controlled by the State (sounds like Planet Earth 2018).

Such a dystopia would’ve been a nightmare for Lewis and Kennedy; but for Huxley, any scenario void of the God of Christianity and ruled by secular oligarchs, was closer to utopia (he did not want there to be a god).

In this Brave New World, we see genetically modified citizens, born in artificial wombs, in a world where the ruling class is superior to the Great Unwashed; a dark technological landscape where the leaders play God and disobedience to the State is forbidden.

Other things forbidden are great works of literature or beautiful, classical art. Such aspects of high culture are banned because they’re timeless and deeply appealing to people, who are now brainwashed to consume new things; besides, in the New World State, citizens wouldn’t understand or appreciate the great artistic works of the past. As long as they are infantile, ‘happy’ and zombie-like, their life of slavish bondage will lie hidden and way beyond their shallow intellectual understanding. A people whose spiritual complacency, moral stupor and lemming-like behaviour resembles that of H.G. Wells’s docile Eloi (The Time Machine).

Huxley wrote: “A really efficient totalitarian state would be one in which the all-powerful executive of political bosses and their army of managers control a population of slaves who do not have to be coerced, because they love their servitude.” In other words, the citizens have deified the State as their God. (Isn’t it strange that the rock’n’roll rebels and anti-Establishment heroes of yesteryear are now replaced with Establishment-worshiping celebrities, ‘musicians’, ‘actors’ and students? It seems today’s leftists just love their ruling-class masters, even to the extent of being their proxy warriors in using identity politics to distract from the economy, poverty and crime.)

As for the inhabitants of Brave New World: For many, technology has replaced God. In the last decades of his life, the existentialist German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) spoke about the threat of technology, as opposed to its benefits. In his book, How to Read Heidegger, philosophy professor Mark Wrathall wrote: “His preoccupation with ‘the technological mode of revealing’ was driven by the belief that if we come to experience everything as a mere resource, our ability to lead worthwhile lives will be put at risk. His task as a thinker was to awaken us to the danger of this age, and to point out possible ways for us to avoid the snares of the technological age.”

It’s possible that later on, movies, songs and events like Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, the song In The Year 2525 and the Apollo moon landings convinced Heidegger more and more of the power and potential threat posed by technology and what it is to be human. In this ‘Brave New World’, efficiency trumps truth, and to be real is to be used as efficiently as possible.

Heidegger scholar Hubert Dreyfus, talking in the BBC’s Great Philosophers series in the early 1980s, points out:

I remember in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick has the robot HAL, when asked if he is happy on the mission, say, ‘I’m using all my capacities to the maximum. What more could a rational entity want?’ A brilliant expression of what anyone would say who is in touch with our understanding of being.

We thus become part of a system which no one directs but which moves towards the total mobilisation of all beings, even us, for their own welfare.

If HAL’s comments are bleak, let’s consider the 1969 dystopian hit, In The Year 2525, by Zager and Evans. The lyrics of the song seem to suggest the Year 2525 might have come a bit early. In recent decades, telling the truth has become a revolutionary act. Once we obey the diktats of political correctness and toe the party line, it seems all will be okay in what we think, do and say.

The lyrics continue: In the year 4545/You ain’t gonna need your teeth, won’t need your eyes/You won’t find a thing to chew/Nobody’s gonna look at you…/Your arms hangin’ limp at your sides/Your legs got nothin’ to do/Some machine’s doin’ that for you.

Heidegger wasn’t optimistic about all this. He believed we might be stuck in the darkest night for the rest of human history. The only hope was that we would get involved in local concerns and other meaningful events might make us appreciate non-efficient practices. We might even meet our future husbands and wives engaging in such activities, with no need to pick our offspring from the bottom of a long glass tube.

Professor Dreyfus again: “I think he has in mind such things as friendship, backpacking into the wilderness, running and so on. He mentions drinking the local wine with friends, and dwelling in the presence of works of art. All these practices are marginal precisely because they are not efficient.” On theological eschatology, it is God and the Second Coming that will decide on the fate of humanity and the fate of the universe. All the transplanting of synthetic parts into humans won’t deter extinction because of the heat death scenario. But before that happens, God will usher in a New Heavens and New Earth (1 Thess. 4.15-17; Rev. 21.1; 1 Cor. 15.51-52).

The crux of dystopian novels or songs point to the terror of existence if we become slaves-turned-cyborgs—if technology ultimately becomes our new god. In 2016, a radio talk-show host on The Kuhner Report told the story of how he and his wife and kids brought his pre-teen nephews on a cruise with them. Throughout the holiday, his nephews were constantly glued to their iPhones and refused to swim, play, talk or engage in fun with their uncle, his wife or children. He lamented with sadness how there would be no fun adventure memories of the trip for his nephews, who had continued to be addicted to their phones even on return home from the cruise.

This story is not uncommon. It’s becoming the story of nearly every parent who sees a blue light flashing from their child’s bedroom during the late-night/early-morning hours. All our technologies give us instant information but the awe of the transcendent is blocked by these cold, technological devices.

The writer Patrick West said utopias will never happen. In an essay in Spiked magazine, he wrote:

Only ideologues and the naive believe in fantasy lands. If people in Iceland, Denmark, Sweden and Finland are the happiest in the world, it’s to do with the fact that they are, in that order, the highest consumers of anti-depressants in the world.

Taking to drugs or to drink is a sign of wanting to escape reality, not embrace it. Humanity is imperfect . . . Only through accepting and embracing strife and woe as the norms can we become better people and create a better world.

And surely it’s better to accept and embrace strife rather than having our arms hanging limp by our sides while some machine is doing work for us? Such machines are expanding at a rapid pace in many industries worldwide.

Our countrysides are already hosting robotic ‘workers’ toiling away on farms, from dusk to dawn. These tend to the livestock’s needs, but there’s also plans to have them watch over crops, while other agri-robots hoe weeds and spray pests.

Experts claim that self-guiding machines will soon revolutionize farming and perhaps redraw some of our landscapes. In conclusion, this got me thinking of a story I once read in a comic magazine many years ago. I think it was in the Warren Publishing horror-fantasy magazine comics, many of which also featured Sci-Fi stories. To the best of my recollection (it was over 40 years ago), one such story had a peasant farmer living alone and exhausted from working on his dilapidated farm day and night.

He finds out that a plant, which grows in a nearby cave, can yield farm ‘workers’. He goes to the cave and picks the plant then seeds it on his farm. The next day, he awakens to find hundreds of gremlin-like demons outside his house screaming for work.

Over a short period of time, he gets them to plough the fields, build extensions to his house, work the farm and build a road to the village. But after they finish a task, they keep coming back to the farmer demanding more work.

In the end, the farmer sits alone in his now mansion, with nothing left for him to do. As he’s slumped on his chair, the head demon approaches him and, once again, demands more work. The farmer says he’s bored, adding: “Give me work.” On that note, the rest of the demons storm the room and rip the farmer’s limbs apart.

It seems the last human to leave the factory won’t have to turn the lights off: leave them on for the robots to continue working—without ever taking a break. Finally, another great secular advantage about working robots—and the billionaires who control them—is they don’t care about fairness, the minimum wage or the Truth.

In the words of Huxley: “Great is truth, but still greater, from a practical point of view, is silence about truth.” Truth is also linked to our past and the foundation of Western civilisation. But the foundations for Brave New Worlds are built on quicksand.

The Christian apologist Ravi Zacharias said that many years ago he was speaking at Ohio State University. “And I was taken to see the Wexner Center of the Arts,” he said. “They wanted me to see it, and I wondered why. And when I walked into that building, I said, ‘What is this building all about?’ There are staircases that go nowhere. There are pillars that serve no purposes. And the man [showing me around] said, ‘This is America’s first postmodern building’, and the architect said, ‘If life has no purpose, why should our buildings have any design or any purpose?’ So he built it at random, without any purpose, as it were. I said, ‘I have one question for you. Did he do that with the foundation as well?’.”

At the end of the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus says: ‘Whoever hears these words of mine, and does them, shall be likened to a wise man who built his house upon a rock: the rain descended, and the floods came, and the winds blew, and beat upon that house, and it fell not, for it was founded upon a rock.’ [Matthew 7: 24-25]

Unfortunately, most of us have built our houses on quagmires. We want God to be what we want Him to be and not what He is. This is tragic, especially as the ends of our lives draw nearer.

As for a Brave New World drawing nearer: Kennedy, Lewis and Huxley are now lying somewhere between Heaven and Hell. Those alive in the land of the living might live to see the day of Huxley’s Godless vision. But only God knows the future—and He’s not impressed with a brave new ship of fools. And where does it leave the devil as he watches the jaws of dystopian technology rise from the eternal seas to devour the crew? He’s gonna need a bigger Hell.

__________________________________

Kenneth Francis is a Contributing Editor at New English Review. For the past 20 years, he has worked as an editor in various publications, as well as a university lecturer in journalism. He also holds an MA in Theology and is the author of The Little Book of God, Mind, Cosmos and Truth (St Pauls Publishing).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link