by Kenneth Francis (May 2024)

Did you know that there is a Peggy Lee song that unwittingly defines atheism? And that the song is allegedly Donald Trump’s favourite? I’ll come to that later, but first, I believe that no secularist acts as if atheism were true. Most 21st-century secular Humanists lead lives similarly moral to those who believe in God. But there is an enormous difference.

From a Christian perspective, the foundations for objective moral values and duties are anchored in God and can be justified. For atheists, there are no objective foundations for morality and no objective justification for having morals in a purely amoral universe filled with atoms bumping into one another. On atheism, righteous indignation is nothing more than a hairless monkey screeching.

On Naturalism (materialism), if there is such a thing as a distorted prototype of ‘the self’, values and morality among such creatures are subjective or arbitrary shared beliefs in what is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ or what functions best in certain situations. And most of these beliefs for Humanist-atheists, not all, are in some ways similar to the theistic worldview on morality, albeit a kind of borrowed morality for the atheist, piggy-backing on the residue of Christianity.

More: In a godless universe, love, self-sacrifice, friendship, relationships, procreation, art and literature, etc, are nothing more than relatively subjective illusions to pass the time and avoid boredom with no ultimate purpose or objective meaning. Such a situation is captured to a tee in Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot, where the main characters struggle with boredom and meaninglessness, as they wait in vain for a friend who never arrives.

If the amoral universe really is just a brute fact, which is scientifically and theistically absurd, then the atheist’s worldview is unliveable unless he or she gets psychologically ‘creative’ or is deluded. In such a Godless world, streets and houses become geometric blocks and plains with cement-shaped objects of all shapes and sizes, void of aesthetics. The sound of Mozart’s Requiem would be nothing more than the primate jungle auditory observations of an ape: Vibrations in the air hitting the outer ear then middle ear, transduced into nerve impulses, then … well, the rest are vibrations, molecules, and sound-wave frequency. You’ll never see a monkey crying at an opera when Madam Butterfly starts squeaking.

Even the literature and information we read occasionally would be nothing more than billions of black, meaningless squiggles on components derived from felled trees and/or computer software, and not in the sense of an English-speaking person reading Chinese, but in the sense of a spider walking across a page of Hamlet, experiencing the physical imagery but not its meaning.

Furthermore, without God, the labours of millions of carers and charity workers worldwide in soup kitchens, shelters for the homeless and the sick and dying, and overseas aid are devoid of all objective values and ultimate meaning. Without God, they would be mere temporary, vanity projects, as death ends at the grave and the universe goes from Big Bang to pathetic icy squeak. Without God, all our accomplishments would ultimately be undone when the sun eventually incinerates the Earth.

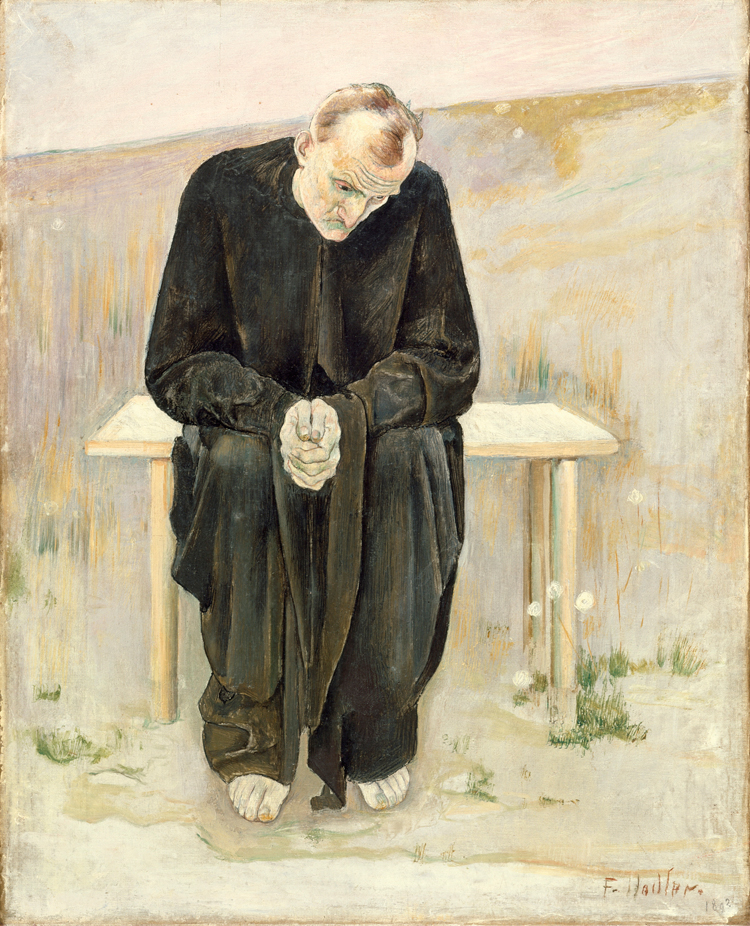

However, as mentioned above, if the atheist lives his or her life as an illusion, and not by a ‘rational atheistic’ worldview that descends into nihilism, is it possible to be a happy individual? Someone who understood the ramifications of atheism, Fredrick Nietzsche, was miserable beyond words and spent his final year insane lying in a bed.

The great Humanist-atheist philosophers of yesteryear acknowledged the hopeless despair that it brings. From Bertrand Russell to Jean Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, they acknowledged that life without God might have transient momentary meaning but it is without ultimate meaning. Is the average atheist aware of the implications of this? And how did they come to the realisation that belief in God was delusional?

In his impressive book, A Secular Age (2007), philosopher Charles Taylor writes about the West’s current age of ‘authenticity’, meaning an individualistic era in which people are encouraged to sort out and make meaning of their own lives. Using reason and experience to find God instilled a sense of intellectual autonomy that led some to abandon God altogether.

Taylor writes that, as a result of this, a so-called “nova effect has been intensified. We are now living in a spiritual super-nova, a kind of galloping pluralism on the spiritual plane.” Paradoxically, that leads some of us back to communal worship (favoured by many Humanist-atheists and their various ceremonies) and to yearn for something more than the self-sufficient power of reason. Some long for ultimate meaning, and that longing may end with God. God is always breaking in, says Taylor, stepping through the immanent frame of secularism. But when ‘secular’ God makes his appearance, Taylor finds he sounds just like Peggy Lee, telling a story, then singing in the refrain chorus: “Is That All There Is?”

This bleak song, which Peggy sung in 1969, is arguably the most depressing song ever written. It was inspired by the 1896 story “Disillusionment” (“Enttäuschung”) by Thomas Mann, and it was later made into a song written by American songwriters Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller during the 1960s.

The song sums up precisely the real meaning of secularism. It tells the story of a young girl and the disappointments she experiences throughout her life. Everything seems empty and tinged with the melancholy of all things done, despite not having done all things.

Finally, totally disillusioned and left with a broken heart when her first love leaves her, her last words confront a way out by suicide. But she says she is in no hurry for that ultimate disappointment, saying in her last breath: “Is that all there is?”

For if there is no God, and this universe is all there is, then it is only logical (if logic exists) to consider Peggy Lee’s song and ‘break out the booze and let’s start dancing’, if that’s all there is. But deep-down, billions of people know that that is not all there is. Even unbelievers seem to intuitively ‘suffer’ from some form of phantom God. For them, consider the following: Do you have an open mind on God’s existence, or is your mind fully closed and impervious to reason and filled with a stubborn intellect pride? If you have an open mind, will you let your intellect lead the way to find out where it leads to? Is a meaningless world all there is?

According to John Ganz, writing in Genius, tapes released by the New York Times, which contain interviews by journalist Michael D’Antonio for his 2014 biography The Truth About Trump, The Donald said this about the song: “It’s a great song. Because I’ve had these tremendous successes and then I’m off to the next one, because, it’s like, ‘Oh, is that all there is?’ That’s a great song actually. That’s a very interesting song, especially sung by her, because she had such a troubled life.”

To answer the character in Peggy Lee’s song in a charitable way, but with a pinch of condescension: Honey, get a grip on yourself and quit navel-gazing. Acedia occurs when one rejects the Logos. You’re looking at the world through the lens of Aergia, the Greek goddess of sloth. In the sentiments of a Ralph McTell song, let me take you by the hand and lead you through the streets of Philly’s Kensington, I’ll show you something that will make you change your mind. And give yourself to God. Then feel the sun in your eyes and the summer breeze on your face, and realise that God, who confers you with free will, also has a plan for your life. Not only are you special, you have the potential to be great, but only through God. However, I empathize with you regarding your trip to the circus. When I first saw a circus, I also asked: ‘Is that all there is to a circus? The clowns ain’t funny and the lions, elephants and dancing bears wearing tutus are being put through Hell.’ But if there is no God, then I apologise, as you are right to ask, ‘Is that all there is?’ Without God, life is more absurd and meaningless than circus bears dancing in tutus.

One is tempted to ask: Why didn’t Russell convert to believing in God? The answer is, Russell’s reluctance to make a leap of faith, based on reason, was theoretically psychological, and not ontological. Same applies to the late atheist icon, Christopher Hitchens. In my opinion, they both wanted moral autonomy.

And consider what the highly distinguished atheist philosopher Thomas Nagel had to say on the fear of God existing: “I speak from experience, being strongly subject to this fear myself: I want atheism to be true and am made uneasy by the fact that some of the most intelligent and well-informed people I know are religious believers. It isn’t just that I don’t believe in God and, naturally, hope that I’m right in my belief. It’s that I hope there is no God! I don’t want there to be a God; I don’t want the universe to be like that. My guess is that this cosmic authority problem is not a rare condition and that it is responsible for much of the scientism and reductionism of our time…”. (Ref: The Last Word, pp. 130–131, Oxford University Press, 1997.)

When your brave father saves you from a burning house, don’t ask, “Is that all there is to a fire?” Thank God you have been saved.

Table of Contents

Kenneth Francis is a Contributing Editor at New English Review. For the past 30 years, he has worked as an editor in various publications, as well as a university lecturer in journalism. He also holds an MA in Theology and is the author of The Little Book of God, Mind, Cosmos and Truth (St Pauls Publishing) and, most recently, The Terror of Existence: From Ecclesiastes to Theatre of the Absurd (with Theodore Dalrymple) and Neither Trumpets Nor Violins (with Theodore Dalrymple and Samuel Hux).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

One Response

You make a case for believing in a deity, by pointing out that earlier generations were able to gain more satisfying meaning to enrich their lives this way. In the Middle Ages the concept of a ‘great chain of being’ was an all-absorbing synthesis.

The trouble today is that belief in a deity tends to rest on a body of rather shaky, vague, unverified, hearsay information, as presented to us by the Bible and other ancient texts. This is a body of messages which —if you believe them— make a lot of sense. But today we expect information to be much more specific, structured and rigorous. It is an unfortunate fact that the guardians of the shaky information have lazily left it in this unsatisfactory condition for countless years. If the putative truths it suggests are valid, they need to be brought up to modern standards of accuracy, verification and cross-examination.

We can do a thought experiment: the reflective minds of antiquity realised that the universe must have been created by a super-mind. How else could it have come about? This hypothesis was, in effect, a no-brainer… until Charles Darwin introduced natural selection and the survival of the fittest. These notions seemed possibly to account for the phenomenon of life, human progress, etc. but they didn’t explain how the physical inorganic universe came about. So belief in a deity was still needed, in a somewhat diminished role.

Today, though, the outlook is more bleak. Computer science and neurophysiology have shown beyond doubt that what we call ‘mind’ is the performance of a brain. But there is no physical super-brain out there in the cosmos to generate a super-mind.

The only mind any human being has ever encountered is the human mind. It follows that, in some very peculiar, self-referential way, the networking-effect of multiple (honest) human minds keeps the universe going. Emmanuel Kant saw this in an outline way 200 years ago. What this networking-effect generates isn’t a deity, but it is the best we can do.