Islamic Reform: Craig Considine’s Bridge to Nowhere

by A.J. Caschetta (October 2019)

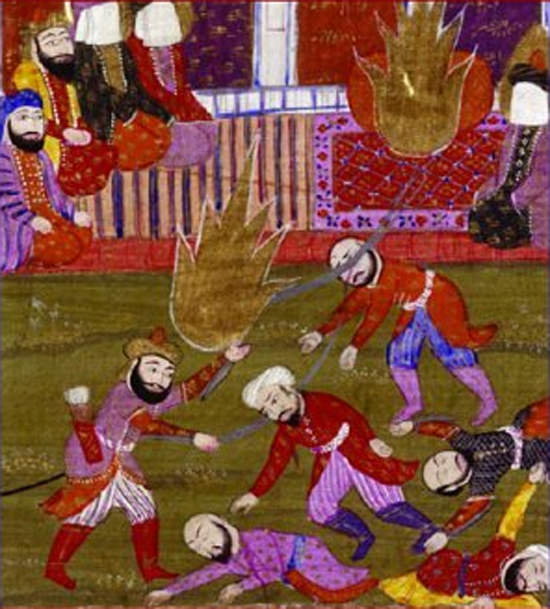

The Prophet, Ali, and the Companions at the Massacre of the Prisoners of the Jewish Tribe of Beni Qurayzah, illustration of a 19th-century text by Muhammad Rafi Bazil.

In the years since 9/11, the Islamic reform movement has advanced sufficiently that two distinct camps have emerged: reformers and bridge-builders. Genuine reformers seek to transform how Islam is practiced, while bridge-builders seek to improve how Islam is perceived, mainly by non-Muslims.

Reformers tend to be Muslims who fault their co-religionists from previous centuries for writing counterfeit stories about the prophet of Islam, and those alive today for believing those stories. Reformers denounce Koranic literalism.

Bridge-builders tend to be non-Muslims or converts who fault those of other faiths for their insufficient appreciation of Islam. They denounce reformers, even Muslim reformers, as “Islamophobes”—a catch-all smear designed to intimidate and silence anyone who criticizes anything about Islam.

Read more in New English Review:

• Trudeau: Politics Without Spine

• An Architect with Aloof Disdain

• The Decline and Fall of Literary Fiction

One genuine Islamic reformer is Tarek Fatah, founder of the Muslim Canadian Congress, who argues that all the hadith are fraudulent and that Islam begins and ends with the Koran. Another, the Australian Imam Mohammad Tawhidi, blames Islamic militancy on “historic texts, generally written by people who never saw Mohammad, and were born centuries after him.” In 2007, the now defunct group called Muslims Against Sharia argued in a manifesto for changes to “Islamic texts, including the Koran and Hadith . . . which call for Islamic domination and incite violence against non-Muslims.” All three, albeit in different ways, refute the authenticity of certain texts, or parts of them, that call for Muslims to dominate non-Muslims.

Bridge-builders come at the issue from the opposite direction by encouraging universal appreciation for Islam and insisting that they alone are capable of deciphering the true meaning of Islamic texts. Some even promote forged texts that depict a very different prophet from the Muhammad of the Koran, Hadith, and Sirat. Not surprisingly, they are often academics.

Georgetown University’s Bridge Initiative, run by John Esposito, a project of the Saudi-funded Alwaleed Center for Muslim Christian Understanding, is designed to engineer mistrust for reformers and smear critics. It even maintains a “Factsheet” on Islamic Reformer Tarek Fatah.

A relative newcomer to the bridge-builders’ club is the social media-obsessed Craig Considine. According to his website, “Dr. Craig Considine is a scholar, professor, global speaker, media contributor, and public intellectual based at the Department of Sociology at Rice University.” He is also one of the most enthusiastic apologists for Islam in all of academia.

Not since Karen Armstrong pronounced that “Muhammad was not a man of violence” has there been a more dubious presentation of Islamic tradition. “Unperturbed by this historical record,” as Ephraim Karsh put it, Armstrong depicted Muhammad’s life as “a tireless campaign against greed, injustice, and arrogance,” and exaggerated his alleged feminist tendencies to an absurd extent. “The emancipation of women was a project dear to the Prophet’s heart,” she insisted. His embrace of polygamy was merely a way “to ensure that unprotected women would be decently married.” And in spite of critics’ objections or the historical subordination of women in much of the Muslim world, the Koran, she enthused, “was attempting to give women a legal status that most Western women would not enjoy until the nineteenth century.”

Considine (R), who makes much of his Catholicism, clearly admires Armstrong, herself a former nun. In an apparent attempt to out-Armstrong Armstrong, he writes, “I consider Muhammad to be a quintessential anti-racist figure because he promoted peace and equality. Without a doubt, he advanced human rights in an area of the world that had no previous experience with this practice.”

Following Armstrong’s lead in attempting to contextualize Muhammad’s behavior within seventh-century Arab standards, Considine presents him as far more progressive than his contemporaries and even compares him to George Washington. Both sidestep all aspects of Islamic tradition that don’t fit their narratives, making them guilty of the same “cherry-picking” they complain about in the work of others. Both rely heavily on obscure passages from questionable sources written centuries after Muhammad’s death. And both ignore any evidence of violence advocated in the Koran, especially the 9th Sura.

Considine’s attempts to demonstrate Muhammad’s compassion are predicated on a series of covenants the prophet of Islam allegedly made with a variety of Christian groups towards the end of his life. Some of these texts were “discovered” and promoted by John Andrew Morrow in a book titled The Covenants of the Prophet Muhammad with the Christians of the World (2013). No “covenant” texts exist in original manuscripts, only copies of copies of “originals” that no one has seen. Logical and chronological problems abound. For instance, one “covenant,” the Achtiname, concerns Egypt, which wasn’t conquered by Muslims until 639—seven years after Muhammad died. In the foreword to Morrow’s book, Charles Upton (who calls himself a “poet and metaphysician”) writes that after the Koran and Hadith, the Covenants may be considered “a third foundational source for Islam, one that is entirely consonant with the first two . . . composed by the Prophet himself during his lifetime.”

Yet Mark Durie (a theologian and acknowledged expert on the subject) expresses the dominant scholarly opinion: “I don’t know any serious scholar who believes [these texts] are genuine.” Many regard them as medieval forgeries, part of a “survival strategy of a victim to praise the abuser and become an apologist for his better side,” says Durie.

Unable to defend the texts’ credibility, Considine’s contributions to this scholarly debate amount to little more than jargon-laden ad hominem attacks. For instance, he charges those who cast doubt on the authenticity of these documents with, “us[ing] ‘the hermeneutics of suspicion’ to widen the gap between Muslims and Christians and to fulfill their own self-fulfilling prophecies about Prophet Muhammad.” This is history twisted to the designs of the historian.

For all his claims to understand Islam, Considine mostly avoids its most important document, the Koran, which is quite hostile towards his Catholicism but in which he sees only “compassion and mercy.” It denies Jesus was son of God (“It befitteth not Allah that He should take unto Himself a son,” 19:35). It denies his crucifixion (“they slew him not for certain,” 4:157). The Koran portrays Jesus as a true prophet whose message was corrupted by his followers, i.e., the Christians, about whom the god of the Koran says “We have stirred up enmity and hatred among them till the Day of Resurrection” (5:14).

In order to accomplish his far-fetched portrayal of Islam’s prophet as an “anti-racist,” Considine ignores Muhammad’s wars against Jews, Christians, and tribal pagans and instead focuses on “Bilal ibn Rabah, a black slave who rose to a leading position within the Muslim community of 7th century Arabia.”

According to the Bukhari hadith, Bilal was owned by Umayyah ibn Khalaf, an enemy of Muhammad. After Bilal converted (or reverted, as the Koran would have it) to Islam and was tortured by his owner, Muhammad sent his friend Abu Bakr to buy the slave. After the hijra (the move from Mecca to Medina in 622) he joined the prophet’s inner circle and was asked to sing the call to prayer. To Considine, this is evidence of Muhammad’s anti-racism.

In 2015 the Arab News published an article by Abu Tariq Hijazi offering Bilal’s story as evidence of “Islam’s respect for human equality, anti-racism and social equity.” Considine again seems bent on one-upsmanship: “the Prophet preceded the words of Martin Luther King Jr., whose ‘I Have a Dream’ speech called for African Americans to be judged not by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.”

Naturally, Considine accepts the flawed convivencia narrative of a tolerant Islamic Spain (Al-Andalus) where Christians and Jews allegedly lived side-by-side in harmony with Muslims who in no way oppressed them. Describing Spain, Sicily, and Portugal as having “Islamic roots” is insufficiently apologetic, so he stretches his revisionist view to the breaking point: “Islam is in their DNA.” In reality these were Christian “spaces” (to use one of Considine’s favorite terms) that were invaded by non-Christian, non-European colonizers who subsequently transformed them into Muslim “spaces,” often by converting churches to mosques. He should put down Karen Armstrong’s book and read Dario Fernandez-Morera’s The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise (2016). Perhaps he will see himself in the description of those whose “selective approach is . . . scholarly defective,” or as another in a long line of academics who “do not want to get in trouble presenting an Islamic domination of even centuries ago as anything but a positive event.”

Many of Considine’s shallow, ahistorical online videos focus on a story about Muhammad allowing Christians to pray in his mosque as if religious pluralism were a commonplace occurrence in the narratives comprising Islamic tradition. It is not.

Perhaps there is some psychological significance to Considine’s failure to acknowledge the concept of dhimmitude—the second class status granted to Jews and Christians (“people of The Book”) who dutifully humbled themselves before their masters and paid the protection money demanded of them. His obsequious, Christian-deprecating hyperbole recapitulates the bowing of a dhimmi before his master. With only vague references to “the jizya, or poll tax for non-Muslims,” and no contextual explanation, he avoids the word “dhimmi.” As Robert Spencer describes it, Considine’s scholarship relies on “a very simple method: ignoring what doesn’t fit his thesis.”

As one who believes Israel is an occupier of “Palestine,” even in Gaza where there are no Israelis, Considine has established camaraderie among various Palestinian Christians who have found a particularly useful idiot in the Catholic professor who supports the anti-Semitic BDS movement and is willing to spread propaganda about Israel’s alleged settler-colonialism and apartheid wall. (About that wall: Considine decries those who build walls—Israel and Trump—yet longs for the day that he can visit the Vatican, blissfully unaware, it seems, that the Vatican is protected by a wall.)

An unskilled polemicist, Considine relies heavily on straw men, particularly “Islamophobes” he imagines are conspiring against him. In one particularly fawning piece in the Huffington Post where “Islamophobia” seemed insufficient, he offers “Islamoracism.” No matter that Islam is not a race, he says, because “scientific research proved long ago there is no such thing as ‘race’ or ‘races.’”

Read more in New English Review:

• The Enemy Within

• The Allure of Politics

• Canada’s General Election

Worse, he ridicules the killers of Muslims but makes excuses for Muslims who kill Christians. As Giulio Meotti points out at Gatestone, “In the same week as the awful attack on the mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand … more than two hundred Christians were killed in Nigeria. There was hardly any mention of the latter in the news.” Nor was there any mention in Considine’s social media.

Craig Considine calls himself a “social media influencer.” The extent of his influence on anyone other than his students (pity them) is unclear, but one thing is certain—that influence is bad. It might just be bad enough to land him a job at Georgetown’s Bridge Initiative, where he would fit right in.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

__________________________________

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast