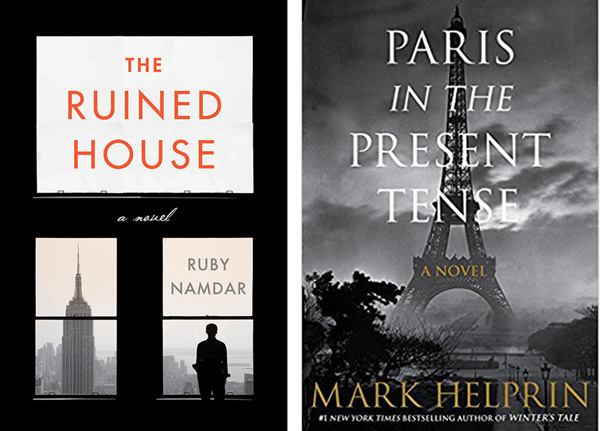

Jewish Memories and Visions: A Review of Two Books

by Shmuel Ben-Gad (February 2018)

t is quite a coincidence that 2017 saw the publication of two Jewish mystical or quasi-mystical novels with certain interesting similarities.

The Ruined House by Israeli writer and current New York resident, Ruby Namdar, is an English translation of his award-winning debut novel published in Israel in 2013. The story takes place in 2001. The supernatural motif becomes evident in the first sentence: “. . . the gates of heaven were opened above the great city of New York, and behold: all seven celestial spheres were revealed, right above the West 4th Street subway station . . .” The chief protagonist is Andrew Cohen (cohen is the Hebrew word for priest and indicates he is of a subset of the priestly tribe of Levi), a respected New York University professor of comparative culture. He seems to be at the height of his powers at age fifty-two and is certainly self-satisfied. He lives in a large apartment and is an aesthete, especially, perhaps, regarding his hobby of gourmet cooking. He left his wife for no decent reason, though he dearly loves his two daughters. (The title of his book can refer, I think, to the devastation he wrought on his family as well as, as we shall see, to the destruction of the Temple, as well as to the felling of the Twin Towers.) A former student of his, a woman half his age, is his lover.

Cohen’s downfall comes when he begins to have visions, predominantly ones of the sacking of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Temple. One of the most important scenes is Cohen’s attendance at a memorial service at Hebrew Union College for the famous Israeli poet, Yehuda Amichai. During the ceremony, Cohen recalls being part of a group on a tour of Jerusalem led by Amichai during which the guide took them to a museum Amichai considered to be fanatical and “insane”. In the museum were facsimiles of implements used by priests in the Temple which were also intended to be used when the Temple is rebuilt. This memory is suddenly interrupted by another vision, after which the shaken Cohen leaves the ceremony, still underway, and seeks out a rabbi at the college to learn about the Temple implements.

From this point on, Cohen goes into a steeper decline—eventually falling into a severe depression. Interspersed with the tale of Cohen is another one set in time of the Temple. In it, the high priest performs his extensive duties on Yom Kippur (the Day of Atonement) during which he is observed by Obadiah, a young priest who suspects the high priest of being a Sadducee and thus, in Obadiah’s eyes, a heretic.

The final installment of the high priest’s tale is related immediately after the memorial service for Amichai. This second, ancient tale, makes the Temple a concrete reality to the reader, not a mere abstraction, symbol, or dream.

Mark Helprin’s latest novel, Paris in the Present Tense, takes place in another culturally vibrant city in 2014 and 2015. Jules Lacour is a university-level cello teacher. He is Jewish, as are many of the book’s characters. Born in 1940, he witnessed the murder of his parents by an SS officer when he was four. He is haunted by the memory of it and also by what he recognizes as an irrational feeling of guilt at not having saved his parents. He is very emotional. For him, music reveals the underlying beauty of the world. Lacour also becomes infatuated with women quite easily and deeply, though he was faithful to his late wife whom he adored. In addition to the quasi-mystical role of music in his life and his powerful attraction to women (especially to a twenty-five year old student of his who returns his love), another great force in his life is his feeling that he has a mission to sacrifice himself for the sake of others. He therefore keeps himself remarkably physically fit by regularly rowing on the Seine.

This sense of mission becomes focused upon his orthodox Jewish daughter and son-in-law (Jules is not himself orthodox though a believer in God) who, as identifiable Jews, face the rising tide of anti-semitism in France as well as on their two-year old son who has leukemia. His concern, however, is not solely limited to his own family; a seminal incident occurs when he rescues a Jew being accosted by Arab youths. While nothing overtly mystical happens in the book, as it reaches its denouement, the role of coincidence comes to play a strong, even unbelievable, role that allows the reader to detect a whiff of the possible workings of God or a supernatural fate.

Both books are character studies of two quite different Jews. In both mystically flavored books, we have central protagonists who are older Jewish men with much younger lovers or would-be lovers. Each man loves his adult daughter but their relationships with them are strained. Each one confronts a huge Jewish tragedy: Cohen the destruction of the Temple, Lacour the Holocaust. Cohen responds with helplessness, panic, and finally banality. Lacour responds by adopting a self-sacrificial, salvific mission which he, with courage and effort, struggles to fulfill in the midst of the attractions of life. Both books are worthwhile reading, even more so when read in tandem.

_________________________________________

Shmuel Ben-Gad is a librarian at George Washington University and a book reviewer for Library Journal and the Association of Jewish Libraries.

Please support New English Review.