by Geoffrey Clarfield (September 2021)

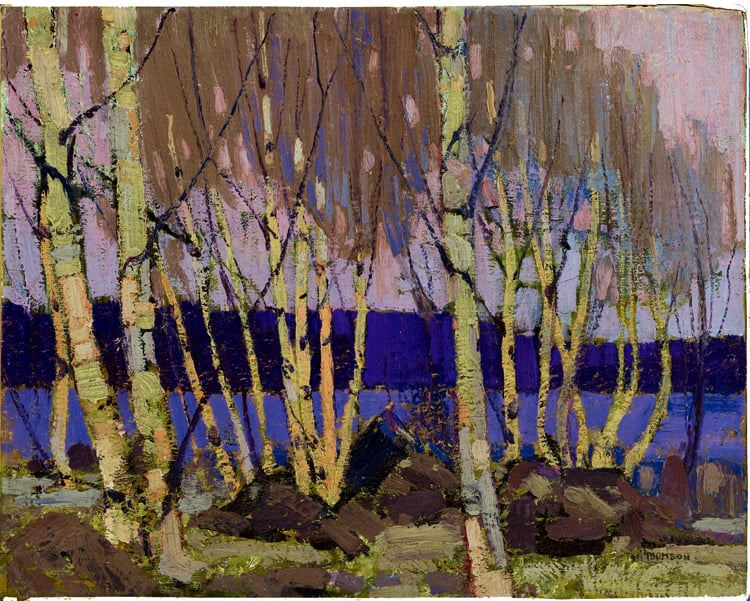

Evening, Canoe Lake, Winter, Tom Thomson, 1915-16

Our young and poorly read Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, has announced that Canada has no core identity, that it is the first postmodern, post nationalist state. Knowing this not to be true I dropped by my friend John Robert Colombo’s house to have a back yard, socially distanced chat about whether this young man knows what he is talking about. He does not and Colombo once again explained to me why Trudeau is not only uninformed, but misinformed. But why should I trust the opinions of an octogenarian white Canadian male?

Well, here are a few reasons. He is in his eighties, but he sounds like a man of sixty. His voice is natural, modulated, he speaks without bitterness and is still possessed by a sense of wonder. He is a husband, a father, and a grandfather. He was not born in Toronto and is not entitled! He was at various times Margaret Atwood’s editor and a promoter of the Nobel Prize winning Alice Munro. He was a friend and poetic colleague of Leonard Cohen. He knew and corresponded with every one of the modern Canadian poets such as Earl Birney and Gwendolyn MacEwen. He was one of the earliest literary managers of the Harbourfront Festival of Authors which, established in 1980, is still going strong. He holds an Honorary Doctorate from York University and is a recipient of the Order of Canada (what would have been a Knighthood back in the days when Canadians could be knighted).

He is a poet, a storyteller, an essayist, an aphorist, a publisher and in the estimation of his colleagues “ a master gatherer,” of other people’s work along thematic lines such as the humour of Canada and Canadians and Canadian paranormal phenomena. He has read many thousands of books and most of the Western classics and, he was a close colleague and confidant of Canada’s and perhaps the world’s greatest modern literary critic, Northrop Frye. I am slowly reading through his recent five-volume collection of essays and thoughts about Canada, “The Notebooks of John Robert Colombo,” and I recommend it highly.

Justin Trudeau is wrong that there is no core identity to Canada. Colombo has spent his working life showing us that there is a Canadian literary mosaic with its own unique take on the world. Colombo’s Canada is a land of wonder, and he has taught me to appreciate the quirky marvelousness of this land where he and I were born.

Colombo has read and published widely about the first nations of Canada whose ancestors came here across the Bering Strait 12,000 years back. He has read their myths and tales and published their poems. He recognizes that Canada had two further founding cultures, the British and the French who provided the political, intellectual religious and artistic frameworks which gave Canadians two competing paradigms from which to begin to view the world. Colombo has catalogued and made sense of Canada’s creativity, its uniqueness, and its low keyed and often eccentric masters of excellence in all fields, who in typical self-deprecating style let other people “blow their horns.”

Colombo is the self-deprecating horn blower of Canadian culture par excellence. I have been reading Colombo for more than a decade because I not only want to find out about the culture that reared me, but want to find out about how other fellow citizens look and have looked at the world. And so, I asked him a few questions. This is what he had to say.

What has interested you about Canada?

I like to say Canada was not my country of birth. Instead, I was born “a British subject” rather than “a Canadian citizen” and raised by middle-class parents in a small Ontario city before the Second World War. The city was (and is) Kitchener, Ont., and it had the peculiar distinction of having no Anglo-Saxon elite to speak of, for it was decidedly ethnic in composition and heavily German to boot. But it could boast a fine Carnegie library. In those days it took me a long time to realize that I really lived in Canada. In the late 1930s there was little sense of being part of a large country, not yet a nation.

My childhood and youth were spent gradually enlarging my “circle of wonder.” So, to me Canada had and has to be discovered. In retrospect, I felt like a newcomer, a discoverer. So, heroes to me are John Grierson, founder of the National Film Board; Tom Patterson and Tyrone Guthrie of the Stratford Shakespeare Festival; and Tommy Douglas, the founder of Medicare. Of interest is the list of “Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Personalities” that appears on the web; it consists of some four hundred names of popular performers, and a goodly number of these nationally known names still elicit emotional responses.

In comparison with today’s on-air personalities, CBC Radio & TV along with the entire commercial broadcasting establishment seem rudderless to me.

Why or what about Canada is interesting?

What I found interesting was discovering little by little that the geography and history of the country, not to mention its intellectual and cultural achievements, were barely known and hardly ever celebrated by its inhabitants who seemed enamoured of what was distant, rather than what was close at hand. I began to collect “Canadian firsts” to fill the void and became something of a bore doing so! “The Great Lakes, so close at hand, comprise the world’s largest surface of freshwater in the world.” “Insulin was discovered in Toronto not one hundred miles away from Kitchener,” etc.

What is the nature of Canadian poetry, prose, and fiction? Is it about “failure” or, being number two, or is there something else there?

I was always a “great reader” and never happier than when I had “my nose in a book.” I soon discovered that nobody except some local librarians like Mabel Dunham valued the earlier writers with a connection with the region, who included W.W. Campbell (a surprisingly interesting poet), and in later years with mystery story writers Margaret Millar and Ross Macdonald as well as David Morrell, the author of the novels on which the Rambo character is based. It was Alberto Manguel who said Canada is the only country in the world where “snow” is considered a four-letter word.

Most literature is about failure on one level or another – pace Chekhov – so I fail to find it to be an overriding characteristic of the country’s literature.

Does the national inferiority complex create healthy overcompensation and excellence in the arts?

I grew up with the phrase “the National Inferiority Complex” which is the local equivalent of the Aussie “Tall Poppy” syndrome, which states with signs and smirks that you have to look elsewhere (especially abroad) for quality in the arts and culture. It was one of my pleasures later in life to meet and know the originator of the phrase, the playwright and philanthropist Merrill Denison who loved the notoriety of being associated with this “putdown.” Merrill thought it was “a hoot” but admitted he never quite understood why Canadians were so cowardly and defensive about cultural expression. (For more details see the commodious volume “Colombo’s Canadian Quotations.”) A footnote to the above, it was Merrill’s first wife who wrote the “Susannah of the Mounties” books, now long and safely out of print.

Are Canadian creatives each obliged to manage their triple heritage—England, France, and the challenge of the USA?

I find the question awkward as I avoid words like “creatives” and “manage” and “heritage.” One would think that Canadians, blessed from birth with two of the world’s leading languages, safe living behind “the world’s longest undefended border” (as it was then, still the longest but no longer undefended), would express delight in this abundant literary heritage, but no, that is not the case.

I found more honest love of literature in the tiny and oppressed Republic of Bulgaria and a more vigorous magazine and book publishing industry there than in the once-styled Dominion of Canada. I visited tiny Bulgaria on five occasions and was mightily impressed with their citizens’ patriotism and love of literature.

How many books, poems, aphorisms, and articles have you written?

I am sure that very few people are interested in sheer numbers, but anyone interested in the matter would do well to check (online or in person) the JRC archives and research collection of Mills Memorial Library at McMaster University in Hamilton. I am represented there with (if I may boast) Pierre Berton, Jack McClelland, Farley Mowat, Bertrand Russell, etc.

How many TV programs have you done?

I estimate that between the years 1960 and 2020 I appeared on two hundred television programs, plus at least as many radio programs, including two national TV series that I hosted on popular quotations and mysterious events. I was always busy on Canada Day (formerly known as Dominion Day) and Halloween eve (those haunts and ghosts, you know!) promoting the current book. I also undertook two national promotional tours for Colombo’s Canadian Quotations and Colombo’s Canadian References. What I quickly realized was that one appearance on Peter Gzowski’s daily CBC radio show “Morningside” was better than two dozen appearances on any other shows or programs.

I was known as “a good interviewee” because in the studio while on the air I watched carefully the host’s body language and listened intently to the host’s vocal expression, for my policy was “it’s the host’s show, not mine,” and what I owed him or her was the invitation to chat with his or her audience of friends. I was invariably invited back. One day in Vancouver, I did eleven “media appearances” in rapid succession with publisher Scott McIntyre driving me from pillar to post. My motto: Be a lively guest and be agreeable.

To my eyes and ears, great hosts who could discuss books included Pierre Berton, Peter Gzowski, Sheila Rogers, Bernard Braden, Robert Fulford, Adrienne Clarkson, Betty Kennedy, Joyce Davidson, and other personalities both regional and national. Eleanor Wachtel of Writers & Company is in a category of her own. What is seriously lacking are weekly regional and national radio and television programs that take books and cultural expression seriously. The producer who did this as well as the late Douglas Cleverdon of the BBC was the late and much-loved CBC radio producer Robert Weaver who had catholic tastes in writing and literature.

Would you agree that the Group of Seven created Canada’s visual language after WWI and that yours created its literary identity after WWII?

Well expressed! There is no question, against much opposition, the Group of Seven introduced to North Americans a new way to see and appreciate the natural world around us. Lawren Harris sensed not only its awesome beauty but also its awesome power, and a decade or so later the poet A.J.M. Smith described it as “broken by strength but still strong.” Smith and his friend F.R. Scott and Louis Dudek, fine poets, introduced “literary modernism” (at Montreal’s Westmount Public Library).

The torch was passed to Toronto in the 1960s and the same creative act was performed by writers of prose like Margaret Atwood and Michael Ondaatje. In 1959, Scott told me that there was only one poet between the Ontario border and the British Columbia border! (Scott even named him.) Now the Prairie provinces alone must be home base to a hundred writers!

How would you describe and classify your output over time?

It’s miscellaneous. It’s a miscellany. It’s bewildering to most readers. That is a characteristic of the oeuvre but not one to be recommended. A writer wishing to make an impression should “stick to his last” and not “cover the waterfront.” I was not interested in creating a single impression, so I did what was of interest to me, with the result there is no “large public” for JRC’s writings because there are many “little publics.”

For instance, I focused on “found poetry” and then on avant-garde poetry and wrote where the Muse took me, a volume of new “poems and effects” every year for sixteen years (so far). No one else had ever attempted this before – or even noted the achievement!

I was infatuated with fantastic literature, so I devoted much time and thought and books to anthologizing Canadian science fiction, fantasy fiction, and weird fiction, defining these fields of wonder. I also collected Canadian jokes and anecdotes (as well as Soviet humour: three books here alone) in a batch of about ten collections.

I surveyed indigenous story and song in “The Dominion Series” of five anthologies of Inuit and Indian eloquence, based on scholarly tomes freshly perused. Philosophy and Literature were my two majors at University College, University of Toronto, so I spent a number of years and three books examining the philosophy of the overlooked French scholar named Denis Saurat, a friend of Jean Cocteau and T.S. Eliot.

Then there are the eight or so “quote books” which attempt to keep alive Canadian expression through the twin interests of scholarship and showmanship. Et cetera. When I last counted, the total number of books (on July 1, 2016) there were 231 titles that had once been in print! (For the curious, the titles of the books are listed on my website www.colombo.ca.)

If you were to give a one semester course on your writings or advice to readers and writers who want the big hits of Colombo what would they be?

I would not want to give a course on my own work, and nobody has ever suggested to me to do so, though I have taught at York University and Mohawk Collage. I do not regard any of my books as “big hits” except perhaps for a couple in strictly commercial terms. I would much prefer to lead a discussion for undergraduates or graduates of the prose and poetry written by fellow Canadians, fiction and verse and essays that were once popular, that has been overlooked, and that should be popular today if only because it “broadens the mainstream.” But most of the books are unavailable. We have always lacked adventurous publishing imprints whose books remain in print and in stores, like New York Review Books, The Library of America, Grove Press, Green Integer, etc.

What happened to Canlit (Canadian literature) and the humanities? What went wrong?

Pierre Berton called the year 1967 “the last good year.” Thereafter technology and the media as well as travel, trade, and commerce went “global,” and the Old World began to catch up with the New World which began to fall behind. The humanities and the teaching of the humanities followed suit. Standards in education collapsed; the effervescent but irrelevant media began to dominate discussions everywhere.

The inhumanities of French Critical Theory as well as Women’s Studies, not to mention Interdisciplinary Studies generally, meant that by and large students were introduced to forgettable nonsense. Thus, would-be textual scholars avoided the labour of preparing annotated texts of classic books by say Northrop Frye, George Grant, and Marshall McLuhan, to name three important Canadian thinkers, and sidestepped the need to read and discuss the challenges of the great critical thinkers of the past and present.

Comments on government funding of the arts in Canada?

For one year I served as a member on three advisory councils concerned with government grants in the literary sphere – with the Canada Council, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Toronto Arts Council. In the 1960s and 1970s, I was impressed with the dedication of my fellow jurors, but by the 1980s, I found the dedication was replaced by the determination of ad-hoc jurors to reward certain writers or to recognize certain regional interests or certain critical theories and practices rather than the talents of writers with national interests and noteworthy aims and standards. So, I gradually withdrew.

I had served as the largely unpaid managing editor of The Tamarack Review for the literary quarterly twenty years of existence, and I turned instead to a decade-long stint of general editing (with pay) of The Canadian Global Almanac which reached a national newsstand-buying public.

Advice to younger writers?

I hate giving advice because there are no panaceas to be had. The older writers I meet need or resent advice; the younger writers I meet express enthusiasm or at least excitement but know nothing of literary history, by which I mean what happened not in the distant past so much as what happened a decade ago and even what is happening elsewhere in the world right now. (How many of them even know that in 2002 the elite journal “Poetry Chicago,” founded in 1912, received a bequest of $100 million? How many of them have even heard the name about Adonis, the greatest living poet of the Islamic world? How many even subscribe to a single worthwhile cultural journal?) But I will share a helpful suggestion: Keep a notebook, diary, or journal; constantly add to it insights and aperçus, descriptions, character studies, and speech anomalies that are heard every day, and keep it up to date with dated entries.

***

I left John’s backyard with a gift of his latest book of aphorisms. Under normal circumstances Colombo would be given a stipend from the Canadian government for near singlehandedly highlighting and promoting “Canadian literary and intellectual excellence,” but with the near dominance of Critical Race Theory in the public schools, colleges, and universities of Canada (from coast to coast) we must hope that a younger generation will one day rediscover Colombo’s writings.

Years back, I well remember walking past the Argentinian storyteller and essayist, Jorge Luis Borges house in Buenos Aires and thinking about the profound impact his essays and stories have had upon my life. One day I am hoping that a young Argentinian will get off the bus at Bathurst and Lawrence, here in Toronto, walk up to the house in question and say to himself, “Colombo once lived and wrote there.”

_____________________

Geoffrey Clarfield is an anthropologist at large. For twenty years he lived in, worked among and explored the cultures and societies of Africa, the Middle East and Asia. As a development anthropologist he has worked for the following clients: the UN, the Rockefeller Foundation, the Norwegian, Canadian, Italian, Swiss and Kenyan governments as well international NGOs. His essays largely focus on the translation of cultures.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast