by Norman Berdichevsky (September 2019)

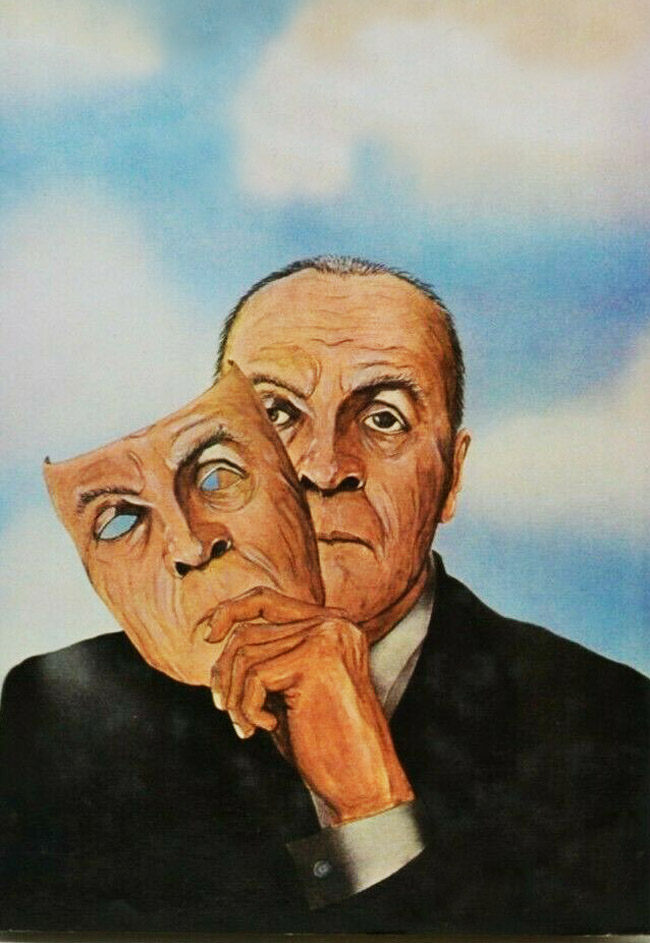

Jorges Luis Borges, Hasted Burchardt for Souvenir Press, 1973

Jorge Luis Borges was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet, and translator, and a key figure in Spanish-language literature. He was born 120 years ago in Buenos Aires. Most Argentinians today would cite him as one of their most illustrious native sons, yet just a short time ago his name and work were an anathema to the ruling elite of the country and moreover, very few Americans or Brits recognize his achievements and reputation today.

Contrast this with the almost universal recognition outside of Argentina of four virtual heroes of the masses with enormous world-wide appeal. Pass any souvenir shop in Buenos Aires and odds are there will be dozens of T-shirts, banners, recordings and other celebrity items on display in the window with images of these four persons. Is there anyone who doesn’t recognize “Evita” (Eva Peron), revolutionary idol of the Cuban Revolution, Che Guevara, football super star Diego Maradona, who earned the nickname “Hand of God” by cheating in a game by touching the ball to score a goal, and tango troubadour and star of a dozen hit films, Carlos Gardel?

The Peronist regime and its successors (another husband and wife couple, Nestor and Cristine Kirchner, were presidents of the country from 2003 to 2015) and used the enormous popularity these four cultural icons to identify with the masses by sharing what they portrayed as the most characteristic traits of a dynamic and mercurial, Argentine “personality,” outward going, patriotic, heroic, manly, and immortalized in the folktales about the gauchos and their rural ethos.

Jorge Luis Borges had to battle all his life to demonstrate his own version of a proud, culturally mature, tolerant, and cosmopolitan nation. In so doing, the Peronist regime utilized him as well as a counterweight in its portrayal of all those traits and political views it detested.

Read more in New English Review:

• Germany, Iran, and Hezbollah

• The Analog Imperative

• Jean François Revel, the Totalitarian Impulse, and Intellectuals

He was linked with sympathy for the Allied cause in World War II and regarded as both pro-British and pro-American government at a time when the Argentine government followed a pro-German course and called for nationalization of foreign owned “anglo-saxon” or “yankee” enterprises.

Borges’ place is now firmly established and he is today regarded as among the country’s greatest writers in spite of the controversy that swirled about him. His works contributed to philosophical literature and the fantasy genre and he is considered by critics as the initiator of what is known as the “magic realist movement” in 20th century Latin American literature. He was nominated several times for the Nobel Prize in Literature and his failure to win it became a source of political controversy for decades

Half a century ago, when Borges’ ground-breaking collection Ficciones was first published in English translation, he was virtually unknown outside literary circles in Buenos Aires and Paris, where his work was translated in the 1950s. In 1961, he was catapulted onto the world stage when international publishers awarded him the first Formentor Prize for outstanding literary achievement. The award spurred English translations of Ficciones and Labyrinths and brought Borges widespread notoriety.

Blindness

He became completely blind by the age of 55 due to a head injury and severe hereditary disease, while he still had another twenty-five years of active writing ahead of him. Scholars have suggested that his progressive blindness helped him to create innovative literary symbols through imagination. Perhaps, this is the reason he did not learn Braille.

Neither the coincidence nor the irony of his blindness as a writer escaped Borges, who wrote

No one should read self-pity or reproach

Into this statement of the majesty

Of God; who, with such splendid irony,

Granted me books and night at one touch.

Born in Buenos Aires, he later moved with his family to Switzerland in 1914, where he studied at the Collège de Genève. The family travelled widely in Europe, and then returned to Argentina in 1921 following the end of World War I when Borges began publishing his poems and essays in literary journals.

The father, Jorge Guillermo Borges Haslam, was a lawyer, and aspired to be a writer. His mother, was an English woman, Frances Ann Haslam. The young Borges therefore grew up speaking English at home and during visits throughout Europe on family trips.

The young Jorge Luis said his father “tried to become a writer and failed in the attempt” and recalled in an interview that

As most of my people had been soldiers and I knew I would never be, I felt ashamed, quite early, to be a bookish kind of person and not a man of action.

Later, as an adolescent, he tuned that shame into pride.

He was taught at home until the age of 11, was bilingual in Spanish and English, reading Shakespeare in the original at the age of twelve. The family lived in a large house with an English library of over one thousand volumes and under his grandmother’s tutelage, he learned to read English before he could read Spanish. The young Borges noted,

It was tacitly understood that I had to fulfill the literary destiny that circumstances had denied my father. This was something that was taken for granted . . . I was expected to be a writer.

Jorge Luis and his sister Norah attended secondary school in Switzerland. He received his bachelor’s degree from the Collège de Genève in 1918. After returning to Argentina, he worked hard at his writing style—by the time he published his first story he was in his late thirties.

Only a very skilled translator can convey some of the surprise and shock that readers in Buenos Aires felt when they first read Borges’ fiction. More than one publisher rejected a manuscript of his by claiming that the work was utterly untranslatable.

His Successes; Ficciones (Fictions) and Aleph

Borges became widely known following the publication of Ficciones and The Aleph. They are compilations of short stories interconnected by common themes, especially dreams, mirrors, labyrinths, philosophy, libraries, mirrors, tigers, roses, map, mathematics, rivers, fictional writers, and mythology. Aleph is the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet and has an esoteric meaning in the Kabbalah, as it relates to the origin of the universe, the “primordial one that contains all numbers”.

In Borges’ story, the Aleph is a point in space that contains all other points. It contains everything in the universe from every angle simultaneously. Borges frequently speculated on this theme of infinity and multiple personalities within the individual.

He also worked as a librarian and public lecturer. In 1955, he was appointed Professor of English Literature at the University of Buenos Aires, and appointed as the Director of the National Library and delighted in the title of “The Ultimate Librarian,” although it was used by his critics to portray him as an intellectual unfamiliar with the active life style and adventuresome nature of the gauchos and military figures who represented national masculine traits.

By the 1960s, his work was translated and published widely in the United States and Europe. All of the images he used reflected upon how the individual views himself amidst the human condition and the riddles of the universe and of existence.

A quick word of warning about his writing: Borges uses a great many semi-colons to subtly suppress most of the three small words we all use so frequently in English (and their equivalents in Spanish ) . . . and, but, and then, showing the connection between two clauses; of course, we cannot see the semi-colons when listening, which is why one has to be careful when reading a Borges passage out loud).

Borges was helped in his career by Victoria Ocampo, an Argentine celebrity, writer, and intellectual, described by him as “The quintessential Argentine woman”. Best known as an advocate for others and as publisher of the legendary literary magazine Sur, she was also a writer and critic in her own right. Her sister, Silvina Ocampo, also a writer, and celebrity, was married to Adolfo Bioy Casares, a close collaborator of Borges.

In 1932, Borges met Adolfo at Victoria’s home. There, she often hosted different international figures and organized cultural celebrations, one of which ended up bringing Borges and Bioy Casares together.

They became instant friends and occasional collaborators. After meeting at the event, they stepped away from the other guests, only to be reprimanded by their hostess. This reproach provoked them to leave the gathering, and a return journey to the city that sealed a lifelong friendship and many influential literary collaborations.

Using pseudonyms, the two teamed up on a variety of projects from short stories to screenplays, and even fantasy fiction; between 1945 and 1955, they directed “The Seventh Circle,” a collection of translations of popular English detective fiction, a genre that Borges greatly admired.

When Jorge Luis Borges wrote the first of three detective stories in 1941, The Garden of Forking Paths, he did so as part of a wider initiative to mark the centenary of the publication of Poe’s The Murders in the Rue Morgue. This year also saw the inaugural edition of Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine promoting excellence in the short story. Borges loved crime and mystery stories because he knew how to provoke the reader’s interest in who the guilty party was and maintain the tension until the very end.

Following the success of his mystery story, Borges formulated 6 rules for writers of crime fiction. For those readers who always wanted to write a detective story—a “whodunnit”—and are familiar with the clever detective board game CLUE, Borges recommended that suspects be limited to no more than six. He discouraged speculation about their psychological make up and clues about their motives, insisting only on the modus operandi.

Gaucho Life on the Pampa

Borges wrote a fictional account of life among the gauchos on the pampa on only a few occasions, most notably in the short stories “South” (El Sur) and “The Dead Man”. He realized their essential role in the creation of the country and wished to show his respect for their strong character and manly virtues but it was clearly the view of someone far removed from their reality.

He even made fun of the sophisticated city slicker who wants to imitate the life of the gauchos as doomed to failure because they lack cunning (perhaps he was writing about himself).

Part of Jorge Luis Borges’s extraordinary writing was in the various forms of non-fiction prose, prologues, lectures, and notes on politics and culture. His writing has often been called too intellectual, and indeed it is dense with allusion. Borges liked parallelism, subtle repetitions-with-variations; his indulgence in “shocking” the reader was the “displacement of adjectives” as in …the readers at their “studious lamps.”

Here is a typical comment of one of many critics (“Minatures of a Giant” by Mildred Adams, New York Times, May 1967):

The myth of Jorge Luís Borges has, for at least twenty years, caught at the minds of people interested in Latin American literature. This man, say his admirers, is not only the great South American writer but great in terms of any geography. However his writing is . . . arcane, over-subtle, an arrogant intellectual who does not bother to make himself understood . . . An abstruse dweller in an ivory tower . . . Argentine by birth and temperament, but nurtured on universal literature, Borges has no spiritual homeland.

Political Engagement

Borges was a strong opponent of the Peronist regime (see Hillary and Evita and their Respective Banana Republics and I Cry for You, Argentina!). He openly expressed his deepest sentiments but not in his writing. He regarded himself as a dedicated Anti-Fascist and Anti-Communist, and detested the regime of General Juan Peron and its ultra-macho culture shared by many working-class Argentinians who were intolerant of gays, feminist women, and Jews. Due to these views, he was attacked as a rich cosmopolitan intellectual and snob, and an enemy of the working class and “ordinary people.”

In 1946, Argentine President Juan Perón began transforming Argentina into a one-party state with the assistance of his wife, “Evita.” Almost immediately, the spoils system was the rule of the day, as ideological critics of the ruling Partido Justicialista (Social Justice Party) were fired from government jobs.

During this period, Borges was informed that he was being “promoted” from his position at the Miguel Cané Library to the post of Inspector of poultry and rabbits at the Buenos Aires municipal market. Upon demanding to know the reason, Borges was told, “Well, you were on the side of the Allies, what do you expect?” Borges resigned the following day.

Read more in New English Review:

• Advanced Artificial Intelligence and Ilhan Omar

• Whisper Louder Please

• The Scourge of Buzzwords

Peronism

Borges believed that Juan and Eva promoted a cult by their policies designed to cultivate the affection of the masses. They were the source of the political movement that embraced the ideal of social justice, playing on the emotions of envy to accommodate the interests first and foremost of the poor. This form of government highly controls and subsidizes many labor unions, strongly supports the military, private industry, and public works.

The Perons: Populists of the Right or Left?

Argentina was pressured by the Allies into declaring war on Germany and Japan in the closing weeks of the conflict. Following World War II (which was economically extremely beneficial to Argentina), the Peronist regime’s inefficiency led to the decline of the country’s economy, the bankrupting of the civil services, profitless industries and the further strengthening of control over labor unions.

Perón’s policies and ideas were initially popular among a wide variety of different groups across the political spectrum. Peron could identify his major target as the great American oil companies in public speeches and yet sign unpublicized lucrative agreements with them. He nationalized the British-owned railroads and some of the largest corporations and, at the same time, protected and won the support of major labor unions that agreed to relinquish the right to strike.

Peron’s treatment of Borges became a famous cause for the Argentine intelligentsia. The Argentine Society of Writers known in Spanish by their initials (SADE) held a formal dinner in his honor. A speech was read which Borges had written for the occasion:

Dictatorships breed oppression, dictatorships breed servility, dictatorships breed cruelty; more loathsome still is the fact that they breed idiocy.

Following the coup that ousted Peron in 1955, Borges supported efforts to get rid of the Peronist cult and dismantle the former welfare state he had created. Borges was enraged that the Communist Party of Argentina that had followed a zig-zag policy of criticism and collaboration with Peron and sharply attacked them in lectures and in print. His opposition to the party and its subservience to Moscow led to a permanent rift with his lover, Argentine Communist Estela Canto.

Borges’ Definition of a Writer’s Duty

During a 1971 conference at Columbia University, a creative writing student asked Borges what he regarded as “a writer’s duty to his time.” Borges replied,

I think a writer’s duty is to be a writer, and if he can be a good writer, he is doing his duty . . . I am a Conservative, I hate the Communists, I hate the Nazis, I hate the anti-Semites, and so on; but I don’t allow these opinions to find their way into my writings—Generally speaking, I think of keeping them in watertight compartments. Everybody knows my opinion.

Both before and during the Second World War, Borges regularly published essays attacking the Nazi police state and its racial antisemitism. In 1934, Argentine ultra-nationalists, sympathetic to Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, asserted Borges was secretly Jewish, and by implication, not a true Argentine. Borges responded with the essay “Yo, Judío“ (“I, a Jew”), a reference to the old “Yo, Argentino” (“I, an Argentine”), a defensive phrase used during pogroms of Argentine Jews to make it clear to would be attackers that an intended victim was not Jewish.

His outrage was fueled by his deep love for German literature. In an essay published in 1937, Borges attacked the Nazi Party’s use of children’s books to inflame antisemitism. He wrote, “I don’t know if the world can do without German civilization, but I do know that its corruption by the teachings of hatred is a crime.”

In a 1938 essay, Borges reviewed an anthology which rewrote German authors of the past to fit the Nazi party line. He was disgusted by what he described as Germany’s “chaotic descent into darkness” and the attendant rewriting of history. He argued that such books sacrificed the German people’s culture, history, and integrity in the name of restoring their national honor. Such use of children’s books for propaganda he writes, “perfect the criminal arts of barbarians.”

In the essay he says that he would be proud to be a Jew, with a backhanded reminder that any “pure Castilian” might be likely to have Jewish ancestry from a millennium ago.

Visit to Chile and Nobel Prize

In later years, Borges frequently expressed contempt for Marxist and Communist authors, poets, and intellectuals. In an interview, Borges referred to Chilean poet Pablo Neruda as “a very fine poet” but a “very mean man” for unconditionally supporting the Soviet Union.

Until his death in 1986, Borges’ name always remained on the lists of Nobel candidates, but they never awarded it to him. Repeated rejections by the Academy had more to do with politics than with literature. Many attributed it for years to the visit he made in 1976 (in the midst of the Chilean dictatorship) at the invitation of the University of Chile.

The Swedish poet Artur Lundkvist, who later was appointed permanent secretary of the Nobel Academy, was an expert in Latin American literature and responsible for the introduction of Borges’ work in his country confirmed that suspicion in an interview: “Swedish society cannot reward someone with this background of having visited Chile and by giving the Nobel Prize to someone who had expressed sympathy with Pinochet”.

Later Personal Life

In 1967, Borges—then 68 years old—unexpectedly wed the 11-years-younger Elsa Astete Millan. A widow, Elsa had been an early flame of “Georgie” (as Borges was known to intimates). The marriage lasted less than three years. It appears that their late-in-life marriage came about for completely unromantic reasons: Borges was blind and needed someone to take care of him. His strong-minded mother was already then in her 90s. Elsa, may have felt some initial affection for Borges, but may have been a middle-aged gold-digger.

From 1975 until his death, Borges traveled internationally. He was often accompanied in these travels by his personal assistant María Kodama, an Argentine woman of Japanese and German ancestry. In April 1986, a few months before his death, he married her via an attorney in Paraguay, in what was then a common practice to circumvent the Argentine laws of the time regarding divorce.

Borges declared himself an agnostic, clarifying: “Being an agnostic means all things are possible, even God, even the Holy Trinity. This world is so strange that anything may happen, or may not happen.”

What Borges wanted us to remember if we wish to become writers, we must use our lives and experiences as the best raw material. He frequently repeated this advice to would-be writers.

Maria Kodama was able to celebrate the inauguration unveiling of a new memorial statue which has since become a place of pilgrimage for many fans of the great author. Even visiting dignitaries including diplomats who may never have read a book, poem, or article of Borges have paid tribute to the man they know is considered as a great cultural figure in the county and as a sign of diplomatic courtesy.

«Previous Article Home Page Next Article»

______________________

Norman Berdichevsky is a Contributing Editor to New English Review and is the author of The Left is Seldom Right and Modern Hebrew: The Past and Future of a Revitalized Language.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link