by G. Murphy Donovan (July 2018)

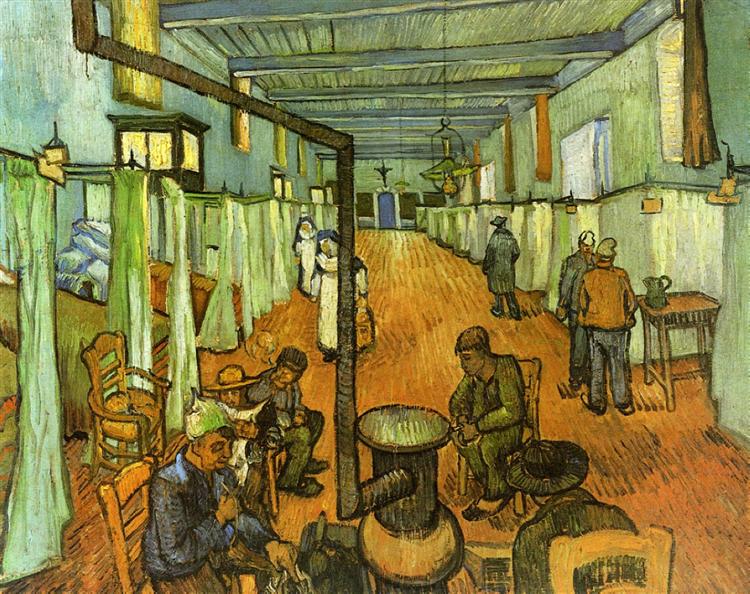

Ward in the Hospital at Arles, Vincent Van Gogh, 1889

Sibley Memorial Hospital, until recently, was a relatively small neighborhood hospital in the northwest corner of Washington, DC. Once upon a time, the food at Sibley, courtesy of Marriot Corporation, was so good that non-patient neighbors would often go to the hospital cafeteria for lunch or dinner. Pot roast and mashed potatoes with gravy anchored the menu back in the day.

Sibley was not on any national “A” list for exotic medical specialties. It was, however, locally famous for patient care, things like an edible food and attentive nurses. Let’s just say, where the latex met the patient, the nursing staff was exceptional—by virtue of performance and reputation.

Sibley was not on any national “A” list for exotic medical specialties. It was, however, locally famous for patient care, things like an edible food and attentive nurses. Let’s just say, where the latex met the patient, the nursing staff was exceptional—by virtue of performance and reputation.

I knew this to be true because I had three distinct surgery experiences; two at Sibley, separated by a decade and a corporate merger.

My first hospital experience of any kind was at the 3rd US Army Field Hospital in Vietnam, a small temporary village if the truth be told. After triage, my injury there was assessed to be minor enough to wait on an IV drip so the staff could deal with the serious carnage of the Tet Offensive. I waited for two and a half days and what I remember most was the “donut dollies,” Red Cross and USO volunteers I believe.

Twice a day, a young lady would stop by every cot or litter pushing a cart laden with coffee, donuts, and magazines. If a patient couldn’t eat, the dolly would just chat. The message that those women sent to waiting or recovering GIs was crystal clear. Somebody cared.

Over the years, I ha ve admired that kind of altruism, peculiar to women it seems. I was drafted for combat while women volunteered, as they do today, to care for the cannon fodder. The stolid nurses at the 3rd Field, like the donut dollies, were all volunteers, angels in mufti.

ve admired that kind of altruism, peculiar to women it seems. I was drafted for combat while women volunteered, as they do today, to care for the cannon fodder. The stolid nurses at the 3rd Field, like the donut dollies, were all volunteers, angels in mufti.

My sister was a veteran of sorts too, a lifetime pediatric nurse practitioner in battle zone Bronx. She ran an out-patient clinic where most of her clients were Hispanic kids. She taught herself Spanish, so she could talk to parents. I once asked her why she didn’t move up to Westchester; better neighborhood, better pay. She gave me the stink eye; reminiscent of the look I got when I asked similar questions of those seraphim back in Saigon.

Care was there because that’s where care was needed. Women do the arithmetic of compassion better than men.

After close to thirty years of service with the Deep State, I retired to the Palisades neighborhood adjacent to Sibley Memorial. One afternoon, I was walking the dogs along the Potomac and became light-headed and winded. Slowly, with many a stop, I worked my way back home where I told my wife I needed to go to Sibley Emergency, some four blocks away.

Anna became apoplectic as I insisted on a shower and change of socks and underwear before departing.

I arrived at the emergency room clean shaven with a pulse of 40 and a blood pressure somewhere between my knees and ankles. I was immediately rendered prone and put on a drip and oxygen. Fortunately, a heart surgeon was making the rounds and he immediately administered some tests and told me I needed a pacemaker. I said “when,” and the good doctor said “yesterday.”

As I was wheeled off to pre-op, I heard one nurse say, “I can’t believe he walked in here.” Another nurse replied: “I can’t believe he was still standing.”

The next thing I remembered was the cardiac recovery ward where I believe there seemed to be one nurse for every four patients. Whilst resting they left you alone. While awake, a cheerful face frequently appeared at the door asking if I needed anything. Seems I mainly needed rest, pot roast, Jell-O, or ginger ale.

I don’t remember ever having to ring a buzzer to use the toilet. I was queried periodically. I don’t remember ever having to ask if I could get up. I was taken on escorted walks regularly. A stroll in a backless hospital gown is a sight to behold.

I don’t remember ever asking about food either. Someone always asked me, monitoring intake—and output.

When I got dressed to leave Sibley that first time, I had a flashback to Vietnam—or maybe just a hot flash of deja-vu. As I rode past the ward desk, I thanked the staff and told them that Sibley was my second-best hospital experience after combat; no donut dollies, but the Jell-O and nurses were exceptional.

I exited to a chorus of laughter.

My recent experience at Hopkins /Sibley was not so hot. In May, I returned after ten years for back surgery, a little stenosis apparently and a lot of pain. My left leg seemed to have developed sleep apnea.

Surgery went well enough, but the recovery ward was a nightmare. In a post-op haze, I was given crackers and juice which I promptly threw up. That was followed by a fistful of pills, one of which apparently was a weapon’s grade laxative. I barely made it to the toilet where, had I an escort, she would have been collateral damage.

I never asked anyone for a laxative.

I was scolded by blue scrubs anyway, for leaving my bed to explode without a hall pass. An unsolicited ambush laxative might not be the best cocktail for a half-starved, drug addled Q-Tip.

Nevertheless, I was admonished yet again not to get out of bed, ever, or take the ten steps to the toilet. My options, however, were bizarre: a bed buzzer, a TV remote buzzer, or a four-digit phone link, all of which amounted to a confusing Orwellian loop. If you hit the bed buzzer, the desk would curtly tell you to call the nurse. If you dialed a four-digit nurse, you got the desk again.

Trust me, the desk doyenne was not happy to hear from you twice. Unlike Floyd Merriweather, a Hopkins aide or tech may not, or does not, have to answer the bell.

All the while, if you are a 75 year old duffer and you have to pee or make a chemically induced deposit, it’s always urgent. Waiting for someone to answer a bell is not much of an option or humane choice—for a lame patient. One aide gave me a walker for emergencies. Just as quickly, the next shift took it away.

I usually sat on the edge of the bed with legs crossed as long as I could. When waiting became torture, I took those ten forbidden steps to the crapper on my own. Eventually, I got caught taking a felonious pee and was rewarded by another tongue lashing and a whoopee cushion. The cushion is alarmed to make rude noises when a patient moves—not unlike an ankle bracelet for hospitalized morons.

No one asked me if I had eaten or wanted to eat either. Food service was like a pizza joint, if you didn’t call, they didn’t haul. In a fit of nostalgia, I ordered one meal, pot roast. Big mistake. Dinner at Sedexo was a hockey puck, a disc of mystery meat garnished with uncooked vegetables.

Marriot was never the Four Seasons, but Sedexo might be a criminal enterprise. My wife prepares better chow for our chickens. How do you screw up a scrambled egg? The irony here is nuclear, Sedexo is a French “food” contractor.

God save the 5th Republic! It’s a safe bet that Sibley CEO Dick Davis does not dine with his family at Sedexo.

Back on the ward, I was seldom asked about bowel movements either. If no one cares about input, output is mute. My wife brought food. We picnicked.

No one ever asked me, or even encouraged me, to take an escorted walk for my entire stay. There was a day, a half hour really, where a therapist ran me in the traces. That PT was my only authorized out-of-bed experience. I left the hospital with a nasty set of blisters on my left side, discovered by my wife I might add.

On day three, I knew why I was sticking to the sheets. The exit nurse concluded that I was allergic to something; vegetating in one spot for three days maybe.

Withal, I was glad to get out of the Hopkins version of Sibley, no fond farewell to the nurses this time around. As an observer of the human condition, I had more than a few takeaways, conclusions that contrast the old Sibley to the “new” Hopkins.

Whence Sibley ?

I suspect that the business and cultural model at Sibley has changed radically under Hopkins. New building and new memes notwithstanding, corporate health care seems to mimic the public school system-model, a kind of expensive, industrial mediocracy.

Like the school system, the chain hospital seems to be populated with minimum trained or minimum wage employees. In short, the folks with the most contact with clients seem to be the least motivated—or qualified. Alas, real RNs make courtesy appearances at shift change, mainly for data dumps it seems. Doctors blow in and out of rooms once a day as if their assets are on fire.

The hour-to-hour patient care, however, is left to scrubs anonymous at the bottom of the pay ladder. It’s not difficult to conclude that rote or ticket punching has become a standard of care. In a hospital fed by the French, ennui is the noun that comes to mind.

Nevertheless, a mind-numbing parade of factotums waddles in and out of patient rooms posting chalk boards, taking vital signs, and punching data into computers, some without so much as a “howdy.” At the same time, hall chit-chat from scurrying blue scrubs provides a day-long unintelligible cranial buzz for patients.

What ever happened to “quiet” in hospitals?

One night (4 AM really) I was jerked awake by a large women trying to wrestle a cuff onto my upper arm. Vital signs, like laxatives, might be sprung on an unwary victim at any hour. Working for Dick Davis is probably a lot like working for Steve Zuckerberg. It’s all about the data, apps, and tools. The healing begins, apparently, when enough data is collected?

Tools indeed!

Alas, recovery anywhere is about intangibles, small things like courtesy, care, food, rest, respect—and comfort. Methinks the comfort train left Sibley when the Hopkins chain crashed the Loughboro gate.

Surely the nursing shortage affects the quality of care, but illness, like war, has always been a tough sell. The personnel problem in hospitals today is not nursing numbers so much as culture. Caring culture, like many other things, seems to have been subsumed by a business, corporate, or data ethic where patients are more object than subject.

Our beloved niece matriculates at Johns Hopkins University this fall, possibly pre-med. We are praying that the Hopkins schoolhouse is not a mirror image of the corporate hospital.

______________________

G. Murphy Donovan, Colonel, USAF (R), usually writes about the politics of national security.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link