Lazy Eye

by Nancy Ford Dugan (January 2021)

Seated Woman, Richard Diebenkorn, 1967

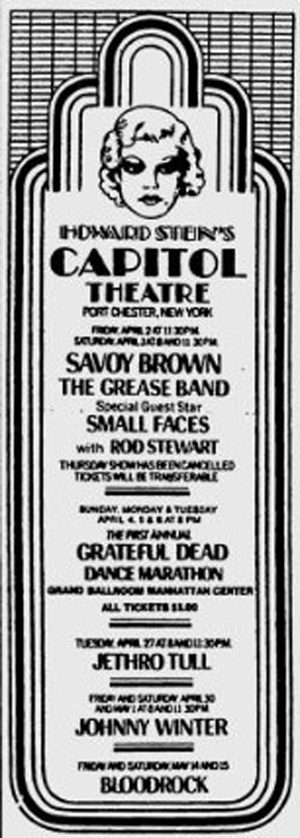

Patti once asked Ron Wood for a Wash ’n Dri. I considered this a perfect example of her confidence and quest for cleanliness, even in the dumpy backstage of the Capitol Theater in 1971.

Ron was quite nice about it and polite. “A wot, luv?” he kept asking. Patti kept repeating “A Wash ’n Dri? You know, to wipe your fingers?” She tried to act out ripping open a packet, using one on her hands.

Ron was quite nice about it and polite. “A wot, luv?” he kept asking. Patti kept repeating “A Wash ’n Dri? You know, to wipe your fingers?” She tried to act out ripping open a packet, using one on her hands.

They were standing about halfway down the skinny staircase that led to the toilet at the very top of the stairs. It had no door and no sink. Patti had just used it, hence her need for the Wash ’n Dri.

Ron’s hair was spiky and perfect. He was all dolled up for the stage in a lavender velvet suit. Patti had a scrubbed, heavy-eyebrowed Ali MacGraw thing going on back then but without Ali’s mysterious, refined sneer. Patti was more snaggle-toothed and funny. She had to be. She had no tits and a fang.

Ron peered at her and tried to register what she was saying, as if she spoke an entirely different language than his. “A wot, luv?” He was weaving a bit and hunched over, a cigarette held between his knobby and multi-ringed fingers.

I was watching this routine at the bottom of the stairs and was frankly impressed. Patti was not only engaging with a rocker about antibacterial products, but she had actually gotten us inside without any tickets and convinced one of the bouncers, a huge guy with a ZZ Top beard and a headband, to block the door frame, with his back to Patti, as she peed.

Patti and I had gone to the same sprawling suburban high school without knowing each other at all. We ended up as freshmen roommates at an urban university down South. We were home on spring break and hence available for mischief.

Patti had a plan to get us in with no tickets. She always had a plan. This one worked.

I had picked Patti up in her part of town, and we drove over to Port Chester in my dad’s Mercedes for the midnight show. My dad was a doctor, a man of science.

It was easier getting out of the house for this adventure than it had been a few years earlier when he and I got tripped up in a conversation that lasted a good five minutes:

Who are you seeing tonight?

The Doors and The Who.

What’s wrong with the front door?

Nothing’s wrong with the door.

Then who’s at the door?

No one’s at the door, Dad.

Who are you seeing?

I said The Doors and The Who.

Why can’t you give me a simple answer? Don’t give me any lip.

Dad, listen to me! The names of the bands are The Who and The Doors. For the love of God, please stop asking me!

What is wrong with your generation?

Patti’s dad was overprotective and drove a Chevy. He would never let Patti drive in the dark, much less to Port Chester, with its reputation for a Westchester version of motorcycle-riding thugs. He only agreed to let her go to the late show (“an ungodly hour for young women to be out and about”) once Patti told him we were meeting up with our other college roommate, Maria, and I was driving. He knew I was, like Patti, a good student, and somehow this meant I was a reliable driver (I was). He trusted Maria, maybe because her late father had been a judge or maybe because she had introduced their family to red onions and romaine lettuce, exotic ingredients they had never tasted before.

Patti bolted out of the house when I pulled up at her curb. She got into the car with a tin of cookies and seemed both excited and aggravated.

“How many times in my life do you think my mother is going to say, ‘Is that what you’re wearing?’”

“It’s only just begun, I’m afraid,” I said.

She laughed. “Yeah, you’re probably right. How’s the traffic?”

“Easy-peasy. Where’s your hat?” It was Patti’s trademark to always wear some kind of floppy hat.

She sighed. “Well, just as I was about to put on the green striped one…”

“Are you okay?”

“Can we smoke in your dad’s car? Want one?”

“No, but you go ahead. Crank the window.” Patti lit up a Raleigh and inhaled. She and Maria were loyal to the brand since coupons came on the pack. Their dorm room overflowed with unused coupons they would never redeem.

“Thanks. So just as I reached for the hat, my mom said, and I quote, ‘You look good in hats…they hide your face.’” Patti turned to me with a “can you believe this shit?” expression. “When she said the first part of that sentence, I actually thought she was giving me a compliment for the first time in history.”

I laughed. “That’s crazy. You know you’re stylish and great-looking. Don’t let her get to you.” At least Patti’s mom was awake. Mine was already in bed and snoring from her scotch and sodas.

“Thanks. Now, how are we going to hook up with Maria?”

Unlike us, Maria had tickets to the show and loved The Faces. She was traveling all the way from upstate New York to see them, so Patti concocted the idea to surprise her at the show.

“Well, first we have to get into the theater,” I said.

Patti’s plan was to bake cookies, wear her newly washed hair in braids, and look as wholesome as the girl on the syrup bottle. Patti’s plan was that she would try to tempt the security guys at the stage door with her cookies, and I was to wear a tight shirt and look sexy. “It’s perfect. I’ll look safe and you’ll look hot. You could also work that lazy eye thing you do that drives the guys wild.”

Patti was referring to my distant stare into the horizon that either made me seem mysterious, bored, or checking out someone else over a guy’s shoulder. Often guys would actually turn around to see who I was staring at. It was a pretty effective technique, I admit, for arousing male interest. My goal was to appear sultry and distant. But to be honest, I really was generally roving and scanning the landscape, looking for someone or something better to come along to intrigue or amuse me.

“They will let us in, I just know it,” said Patti.

That’s pretty much what happened. We got in, though I think Patti was hurt that the ZZ Top wannabe guy laughed out loud when his boss said to let us in since Patti obviously was NOT a groupie.

Once we were in, Patti had to pee and asked ZZ for the ladies room.

“The ladies room? What do you think this is? There’s no ladies room, girly.”

After Patti convinced him not only to show her somewhere to pee but also to block at the door, and after her encounter with Ron, ZZ said, “Okay, kid, that’s it. Now be quiet and stand over here.” He walked us to the side of the stage where we joined a bunch of emaciated, possibly underaged, straggly-haired dirty-blonds in granny dresses. They looked like they’d escaped from team Manson.

Patti tried to talk with them, but we both quickly realized they were incredibly drugged and listless; to be honest, the correct word would be stupid. I know what you’re thinking: who was I, a college girl, to judge them? There but for fortune, as Joan Baez drummed into us all.

Patti was horrified. “What are you doing with your lives?” she asked them. They talked about who slept with which band member, clearly swapping themselves to suit the band guys’ whims. “Don’t you get emotionally attached?” asked Catholic Patti. “Okay, ladies, we need some consciousness-raising.” Patti started to talk with them about Gloria Steinem, about education. We had a mini feminist session. Some of them asked us about college.

The first band started to play. New Riders of the Purple Sage.

Patti and I didn’t really care for them. The granny-dress girls swayed to the music even though it was hardly sway material.

“And where do you suppose Maria is?” Patti peered slightly around the curtain to glimpse the crowd. The drummer looked annoyed when he noticed this. He looked over at me and I lazy-eyed him.

“How will we meet up with her?” Patti spent the set figuring out a plan for that.

ZZ showed up after the first band had finished and asked Patti if she could manage the liquor distribution for The Faces as they performed. It had to be handed out to Rod Stewart and the other musicians, including Patti’s staircase buddy, Ron, in a particular logistical order: certain songs got certain bottles. “Sure,” she said. She had a job!

An elaborate rolling cart appeared. Patti got the set list and a crash course in when to provide the Mateus, Southern Comfort, Jack Daniels, etc. The cart was filthy, beat-up, and creaky but somehow distinctly elegant and grown-up. Or maybe just British.

“Wouldn’t it be funny if we served them hot tea instead?” said Patti. “Maybe that would help Rod’s gravelly voice. My grandmother had one of these tea trolleys, I think. Believe it or not, she was British.”

I believed it.

“Okay, now I have to concentrate on doling out the booze.” Patti started alphabetizing the clinking bottles. “Maybe you can keep an eye out for Maria?”

But I didn’t. I got into the music and danced throughout their set. Rod tilted way back at an angle when he sang, head facing up to the ceiling, tapping his front leg in front of him like a pre-Derby racehorse. After each number he seemed concerned. He’d turn expectantly and doubtfully in the direction of clean-cut Patti and the cart. She’d optimistically hold up what she hoped was the right bottle, and he’d nod, grab it, and take a swig, sometimes returning it to her, sometimes placing it on the floor of the stage.

I bet Patti was wondering if she should swoop on stage and get the bottles, giving her a chance to prove her general efficiency and also to stealthily try to spot Maria in the hopped-up crowd. But she didn’t.

Before the encore ZZ told everyone in the wings to take the stage and sing along to “Sweet Little Rock and Roller.” Patti and I marooned ourselves near the curtain and let the groupie girls get more stage space and dance room. It was the least we could do. We were intruders, they were the pros. We weren’t in the band, we weren’t with the Mansonites. We were just crashers.

That didn’t stop Patti from singing along, even though she really didn’t know the lyrics. Then I realized she was using the moment and the din to call out, “Maria, Maria, we have a car” while she waved and looked up at the cheap seats, just in case Maria could see us. Maria, Maria. It sounded like West Side Story all of a sudden.

But we never hooked up with her. Maria later told us that she did come out of her druggy, booze haze in the balcony boonies for a moment and thought she recognized us. “That looks like Patti,” she told her upstate friends. “Or I’ve had way too much to drink.” She started waving but Patti was suddenly yanked off the stage. Rod had been startled by her Sondheim routine and ZZ dragged her away. I reluctantly followed, bummed to be out of the spotlight.

We slunk outside to my dad’s car, evicted from the fun. I guess I was hoping for something more. I guess I was also annoyed that Patti may have ruined our chance—well, my chance, anyway—to party with the band. Without Patti I never would have thought to go to the show. But with her I was now restless and wondering if I had just missed out on some bigger, wilder adventure.

Instead we drove in the dark though the eerily quiet suburban streets. I was eager to drop Patti off and get home, to sort out my unsettled disappointment.

“Do you think maybe Maria saw us on stage?” asked Patti.

“It’s totally possible,” I said, though I doubted it.

Being with my roommates often made me feel like we were on the edge of something, a discovery of what the world could present to us, like the choices on the rolling cart. I yearned for a divine clue, a revelation about what we could do and be in this world, something different from our mothers, who were stuck in their suburban homes.

“My mom is going to freak out that I didn’t bring her cookie tin back,” Patti said. She yawned and patted her head. “Well, for a hatless night, it was pretty eventful. Though I am sort of bummed we didn’t get to see Maria. I hope she enjoyed the show.”

“Did you?”

“Sure. I’m sort of proud of us and surprised that we got in. Aren’t you? Gotta tell you, I was also surprised how small and skinny all those guys are. My left leg weighs more than they do.”

Patti and I were tall girls and proud of it. We didn’t try to shrivel and be petite. We liked to make an entrance.

I laughed. “Yeah, except for your friend the bouncer.”

“He was massive! Guess that’s the job. We owe this entire evening to him.” I pulled into her silent lane with its Tudor homes and sweet smell of spring from the newly blooming trees.

“Thanks, doll,” said Patti. “I guess, like Maggie May, we really should be back at school next week. See you then.”

Alone on the quiet ride back home, I felt like I was floating down the empty, curving streets or riding a wave I wanted to be on but didn’t know how to surf. I turned on my dad’s smooth jazz radio station, which made me feel even more disoriented. Shouldn’t jazz be raucous, not smooth?

No one was around. I considered running a stop sign or jumping a red light. Or speeding up to fly over the dip at the bottom of the hill on Jefferson Avenue. But I didn’t.

We had successfully crashed a concert, thanks to Patti. But I realized we were too cautious and we always would be. We were raised to be competent and dutiful, to remain on the edge but not really participate.

This seemed a tragic and deflating notion.

Patti and I would grow up. We’d graduate (unlike Maria, who had already flunked out yet continued to live and hide in our dorm room until she figured things out). We’d work at jobs in our fathers’ industries, for cruel bosses and kind bosses and everything in between. We’d put up with crap and bad politicians and occasionally march in the streets about it. We’d make our own money but less than we’d deserve. We’d lose touch with each other. We’d be independent and tall and carve out some kind of life with and without men who might love us or not love us, men who would crumble or dodge. We’d end up on thyroid medications, like our mothers. We’d take care of and comfort our family elders. Our hearts would break over things that happened and even more over things that didn’t happen. We’d wear seatbelts and stop smoking. Maria wouldn’t do any of these things.

I’d have to stop using the lazy-eye technique because it confused people.

Patti could wear any damn hat she wanted any old time.

Maybe we’d be forever bland and boring, but we’d pretty much be fine. We’d be lucky and self-preserving. We’d survive into another century. And so would Maria, even though she never really figured things out. But then neither did we.

But what I really want to know, what I still cannot seem to get an answer to and so I pose this question to you: Is being boring and lucky enough? Is it enough for the “one wild and precious life” the poet talks about?

I’d really like to know. Tell me now. Please.

__________________________________

Nancy Ford Dugan has been nominated twice for a Pushcart Prize and has appeared in over 40 publications, including The Diverse Arts Project, Dream Catcher Literary Magazine (UK), After Happy Hour Review, Blue Lake Review, Limestone, Caveat Lector, Crack the Spine, Cimarron Review, Cobalt Review, The Healing Muse, Passages North, The Minnesota Review, Hawaii Pacific Review, Glint Literary Journal, Euphony, The MacGuffin, Epiphany, Delmarva Review, Hypertext, The Doctor T.J. Eckleburg Review, Lowestoft Chronicle, Paragon Journal, Penmen Review, Slippery Elm, Superstition Review, and Tin House’s Open Bar.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast