Leadership Organizations Proclaiming to Promote Free Expression

by G. Tod Slone (December 2022)

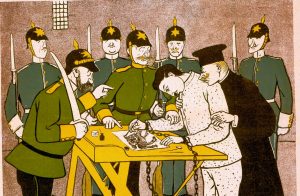

A Cartoonist and his Captors, from the German satirical magazine Simplicissimus, 1906

As a former college professor, one thing I certainly learned was that if one openly criticized the college administrators, one would inevitably be punished for doing so. I certainly experienced that at Elmira College, Bennett College, Fitchburg State University, Grambling State University, Davenport University, and American Public University.

As a poet, writer, critic, and cartoonist, I also learned that if one openly criticized CEOs, directors, publishers, editors, cultural apparatchiks, and other so-called leaders, one would inevitably be ostracized into non-existence. So-called “leaders” tend intrinsically to despise free expression because it inevitably threatens their leadership fiefdoms of control. Future leaders learn, while climbing the ladder to attain leadership positions, to turn a blind eye—see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil—the exact opposite of free expression. In a nutshell, leadership and free expression cannot coexist. And so, what to say when leaders decide to (sort of) promote free expression? Mind-boggling!

Inside Higher Ed published an essay advertisement, “A Free Expression Strategy,” penned by the top two leaders, Jim Douglas and Chris Gregoire, of the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Academic Leaders Task Force on Campus Free Expression. Douglas is a former Vermont governor (politician!) and current Executive-in-Residence at Middlebury College, while Gregoire is a former Washington governor (politician!) and CEO of Challenge Seattle, “an alliance of CEOs from 21 of the region’s largest employers.” Middlebury College has had a horrendous free-expression record for a number of years, while Seattle is a bastion of pc-ideology, the very opposite of free expression. For both Douglas and Gregoire to succeed in rising to the top rung of the political ladder, free expression had to remain behind on the bottom rung. Politics and real free expression cannot coexist, nor can careerism and real free expression. Democracy dies in careerism!

As for Inside Higher Ed, a corporate news entity, it is against free expression, especially when it concerns it and its editors, Doug Lederman and Scott Jaschik, not to mention its CEO (yes, it has a CEO!) Dari Gessner. It has censored and ignored my comments for over a decade. Read my essay, “To Censor or Not to Censor—Notes from the Censored: An Examination of Inside Higher Education’s Comment Policy,” which was certainly not published in Inside Higher Ed, but rather in the Journal of Information Ethics. IHE finally decided in 2020 to simply eliminate its comments sections. Read the justification for that termination of free expression by editors Lederman and Jaschik: “An End to Reader Comments.” Other criticism I’d written and sent to the two editors include “Censoring Conversation in the Name of Conversation: Only in Higher Education” and “Censored Yet Again on Inside Higher Ed,” as well as several aquarelles satirically depicting them: “Inside Moderated Ed” and “The Higher Education Moderator.” For an example of my censored comments, examine “As Tenured Academics Weep Crocodile Tears over the Faltering Economy….” Well, to my great surprise, I actually managed to extract a comment from editor Doug Lederman, regarding the criticism I’d cc’d to him on Professor Jonathan Zimmerman’s Inside Higher Ed opinion article, “My Amy Wax Problem.”

Great to hear from you, Tod.

And that was all! Snarky or bona fide embrace of free expression and vigorous debate? In any case, Douglas and Gregoire argue that “free expression controversies have eroded confidence in our colleges and universities as true homes to open inquiry and as forums to prepare the next generation of civic leaders.” Perhaps they should have then presented a three-step initiative, which would have certainly helped enhance their credibility. The first step would constitute an attempt to convince the two IHE editors of the importance of real free expression in higher education, as opposed to word-salad justification of its restriction.

The second step would be for Douglas and Gregoire to consider opening their own doors to criticism, especially with their own regard. The third step would be for them to vigorously encourage the current generation of so-called “civic leaders” (e.g., the department chairs, deans, and university presidents) to open their doors to criticism, especially regarding themselves and the organizations feeding them. Douglas and Gregoire’s failure to take any of those steps would be indicative of a virtue-signaling (vacuous) charade.

The two leaders note that “A recent national poll conducted by Morning Consult on behalf of the Bipartisan Policy Center found that while more than 80 percent of adults believe it is important for colleges and universities to teach students the skills of independent thinking (88 percent) and working with a diverse range of people (85 percent), only about half believe that colleges are doing well at teaching these skills.”

What the two leaders fail to delineate is what precisely constitutes those “the skills of independent thinking.” And are they really “skills”? When so-called leaders emphasize team-playing, as they tend always to do, they end up inevitably denigrating (and punishing!) “independent thinking,” which demands strong individuality and even stronger courage to stand up and speak… at the risk of being punished for doing so. Read my “Notes on Risk and Writing.” As a professor, I certainly exercised “independent thinking” and for doing so ended up fully ostracized and eliminated (see, for example, “Fitchburg State University (Fitchburg, MA)—Free Speech in Peril.” And yes, personal experience with academic corruption is fundamental to the real understanding of the problem, in this case, requisite absence of free expression. Most professors are careerists. Careerism demands team-playing and highly restricted “independent thinking,” a virtual oxymoron. So, are individuality and courage prime ingredients for “independent thinking” skills? Can they actually be taught in a milieu where team-playing and careerism are of utmost importance? Focus on one statement made by Ralph Waldo Emerson could serve in that endeavor:

I am ashamed to think how easily we capitulate to badges and names, to large societies and dead institutions. Every decent and well-spoken individual affects and sways me more than is right. I ought to go upright and vital, and speak the rude truth in all ways.

In essence, one would have to learn what academe generally does not teach. In creative writing, for example, one would have to learn to question and challenge, as opposed to simply admire the icons (the laureates, the Pulitzers, the inaugural poets, etc.) normally pushed by the professors. One would have to learn to question and challenge the entire literary establishment, which inevitably includes the creative-writing professors themselves. Yet how might an establishment professor encourage and teach that?

The two leaders state: “In the 2022 legislative sessions, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures’ bill tracker, bills touching on campus free expression have already been introduced in 19 states. As former governors—one of whom has spent a decade as a faculty member—we think that the solutions to these issues do not come from the statehouse, but from campus.”

Well, as noted, Douglas’ record as a faculty member at Middlebury College seems to have been fully ineffective, if not outright deplorable… regarding free expression. The campus absence-of-free-expression problem has only gotten worse, thanks to the metastasizing of diversity deans and their racist wokeism ideology. Public colleges and universities are legally bound to the First Amendment (i.e., free expression). Lawfare is the real problem. One can have rights. But one can also be punished for exercising them, legislative bills or not. If the latter occurs, one needs to hire expensive lawyers to rectify the situation, especially when pro-bono lawyers, whatever the reason, will not help. My case against Sturgis Library serves as a personal-experience example. The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression responded to my recent pro-bono request:

Dear Mr. Slone—

Thank you for submitting your case to FIRE. I have reviewed your submission and have discussed your situation with my colleagues. Unfortunately, FIRE is unable to offer direct assistance in this matter. Please do not interpret this as a judgment on the merits of your claims. FIRE simply has limited resources and receives a remarkable number of requests for assistance.

If you believe you might benefit from legal advice or representation, you should consider obtaining the services of a private attorney as you contemplate how to proceed in this matter. If you require assistance in locating an attorney in your jurisdiction, we recommend your state bar association’s Lawyer Referral Directory.

You should also be aware of the fact that failing to bring a claim within the time-frame set by the law could prevent you from pursuing a lawsuit or other action. We have not researched these time limits, which can be very narrow, and we are unable to advise you on what time limits may be applicable to your situation. We urge you to contact a lawyer promptly if you wish to pursue any legal claim you might have.

Again, I am sorry that FIRE is unable to offer specific assistance, provide legal advice, or represent you in this matter, but we wish you the best in your pursuit of justice.

Sincerely,

Adam B. Steinbaugh

Attorney

Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression

Douglas and Gregoire’s “task force” created “a strategic guide for campus leaders” (who tend inevitably to scorn free expression whenever they’re concerned): “Campus Free Expression: A New Roadmap.” The two leaders argue that “One focus for the task force was understanding why fostering a culture of free expression has become increasingly difficult as Generation Z has arrived on campuses. It’s not enough to have a free expression policy or statement.” In essence, de jura vs. the reality of de facto. And, again, to obtain de jura one normally has to hire expensive lawyers or if fortunate have a union lawyer, something I had way back when. Just the same, the latter did not succeed in protecting my free expression right and preventing me from getting axed.

The two leaders seem to be cautiously, if not obediently, employing terms that actually serve to kill free expression: “One challenge is the perceived tension that pits academic freedom and free expression against diversity, equity and inclusion in creating a respectful environment for all students.” “Respectful” is one such term. The two leaders do not seem to really comprehend the legal definition of free expression, which does not include “respectful.” They argue that “While not ignoring that there is expression that is hurtful, we believe profoundly that free expression is an essential means to an inclusive campus in addition to being essential to the mission of higher education. After all, it is through respectful, serious conversation that we understand others’ viewpoints and we learn empathy and compassion for those different from ourselves.”

Terms like “hurtful,” “respectful,” and “serious” tend to be highly subjective, thus highly manipulatable by so-called academic leaders… in an effort to kill free expression. Intrinsic cowardice seems to be a trait of most students, professors and academic leaders, which is why, “The other main challenges we [the two leaders] identify include a lack of viewpoint diversity on many campuses, the ability of a censorious minority to chill expression of opinions and self-censorship by students and faculty that subtracts from the fullest discussion of ideas and opinions.”

To keep ones job, one must self-censor. To rise to the position of “leader,” one must self-censor. Douglas and Gregoire fail to address that crux: “They [faculty members] must enjoy robust protection of their academic freedom in their classrooms, scholarship and extramural activities.” The problem, again not addressed, is, well, summed up quite nicely—rude truth’ely—by Charles J. Sykes in his book Profscam:

Tenure corrupts, enervates, and dulls higher education. It is, moreover, the academic culture’s ultimate control mechanism to weed out the idiosyncratic, the creative, the nonconformist.

The two leaders note that “The report includes a sample of tabletop exercises—hypothetical scenarios of free expression controversies—suitable for leadership teams, faculty and staff to think through how to build a campus free expression culture that suits their campus’s unique history and mission.” The first exercise, which no doubt is not included in their report, ought to be how to deal with a rogue professor who openly criticizes administrative corruption. The second exercise, which no doubt is not included, ought to be how to rectify the corporatization of free-expression-adverse academe and academic media, including Inside Higher Ed and the Chronicle of Higher Education. In essence, the leaders need to deal with their own problem first. Unfortunately, for Douglas and Gregoire, that problem seems not to exist. And indeed they conclude: “Building student resiliency for the adult world of active citizenship ultimately requires a campus culture of robust intellectual exchange, clarity, rigor, empathy, respect and humility, all of which reinforce widespread community trust.”

What is desperately needed is a statement that begins with: “Building leadership resiliency…” Also, highly subjective terms (e.g., clarity, rigor, empathy, respect and humility) need to be eliminated, for, again, they serve to kill free expression. So-called leaders, Douglas and Gregoire included, need to build backbone and not only brook hardcore criticism, but actually encourage it, especially with their regard. Otherwise, their free-expression strategies will be nothing but hot air flowing from the mire of academic business-as-usual. This is a war: ideology vs. free expression. One normally does not wear a tie and jacket on the battlefield, which is precisely what Douglas and Gregoire seem to have chosen to adorn.

This essay was sent to Douglas, Gregoire, Lederman, and Jaschik. No response has been received.

Table of Contents

G. Tod Slone, PhD, lives on Cape Cod, where he was permanently banned in 2012 without warning or due process from Sturgis Library, one of the very oldest in the country. His civil rights are being denied today because he is not permitted to attend any cultural or political events held at his neighborhood library. The only stated reason for the banning was “for the safety of the staff and public.” He has no criminal record at all and has never made a threat. His real crime was that he challenged, in writing, the library’s “collection development” mission that stated “libraries should provide materials and information presenting all points of view.” His point of view was somehow not part of “all points of view.” He is a dissident poet/writer/cartoonist and editor of The American Dissident.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast