by Theodore Dalrymple (May 2024)

There are some countries that leave, even after the briefest of visits, an indelible impression on the mind. You leave the country, but the country doesn’t leave you. This may be for more than one reason, not the least of them political. I don’t think that anyone who has visited North Korea is likely to forget it in a hurry.

Of the same ilk is, or was, Albania under its communist regime. That regime exercises a fascination much beyond its apparent size, reach or importance to the rest of the world. The Albanians broke with three successive communist sponsor countries, Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union, and finally China, claiming thereafter to be the only truly Marxist-Leninist state in the world. Albania’s leader, Enver Hoxha, the most graphomanic of all the communist leaders, poured out his literary vitriol on all the others with an inexhaustible flow of bile. They of course deserved all the bile that could be poured on them, but not from one who was among the worst of the whole lot.

It is not possible in a paragraph or two to convey the full scope of the Albanian tyranny. My brief sojourn there—a week—was after Enver Hoxha had died, when the country was still ruled by his faithful disciple and acolyte, Ramiz Alia, and Hoxha might just as well not have died for all the fundamental changes there had been. The fact is that no dictatorship, no matter how personalised or totalitarian it may appear to be, relies on a cadre of servitors; and these servitors have much to fear from a real change of regime, for they have been the accomplices, often more than willing, of its crimes. They are like jugglers who must keep the balls in the air, or the whole act fails.

The cult of personality persisted though the personality had departed this life. He was known simply as Enver, no other name being necessary (I wonder how many children born today in Albania are given that name?) to identify the person referred to. On many hills—and a large part of Albania is mountainous—the words Enver – Parti were inscribed in white stones, like the menhirs of some primitive religion. Not, of course, that religion of any kind was permitted in Albania, which prided itself on being the first, and only, religion-free country in the world. Mosques and churches (the population was of 70 per cent Moslem descent) were used for purposes other than worship, for example the storage of grain.

Crime and paranoia were institutionalised, so to speak. There were no boats along the whole of the country’s coast, lest anyone tried to flee the people’s paradise (Corfu in Greece being only a couple of miles off). Anyone who tried to leave was executed; his family would also be held responsible, for collective responsibility was the reigning juridical principle.

The whole country was dotted with concrete gun emplacements, like smaller versions of Oscar Niemeyer’s concrete dome of the former headquarters of the French Communist Party in Paris. Their number has been variously estimated at between 500,000 and 750,000: a considerable, and mad, effort for a country of fewer than 3,000,000 people. Hoxha was convinced that Albania would be invaded by the imperialist powers; he never seemed to have grasped just how unimportant his country was to the rest of the world. On all the poles supporting vines there were steel pikes to impale the invading parachutists. The best thing one can say about the communist regime is that it left Albania the country the best-provided with public lavatories in the world.

Oddly enough, there were, in all western countries, groupuscules of sympathisers with the far left that took Enver Hoxha at his own estimate. Albania under his rule was to some communists what the Plymouth Brethren were to some Christians. There was a bookseller not far from where I once lived who was a communist of the Albanian persuasion. He was culturally extremely conservative, and he refused to use the internet to decide on the prices of his books because he regarded it as a means of enslaving the proletariat. Bargains were to be found in his shop, but in vain did I draw his attention to the fact that they were worth much more than he charged. Since he was ideologically opposed to the operation of the market, his prices reflected what he thought the books were worth rather than what they would fetch. His shop was well-stocked with the many volumes of Enver Hoxha’s bilious autobiography but, as far as I am aware, I was the only person who ever bought one. In vain, did he try to persuade old black ladies that they would be better off with Hoxha than with the bible or devotional literature, but he was convinced that history, or rather History, would vindicate his faith. I look back on him with both amusement and affection, as a harmless eccentric, though I might have felt very differently had I been an Albanian forced to live under the regime.

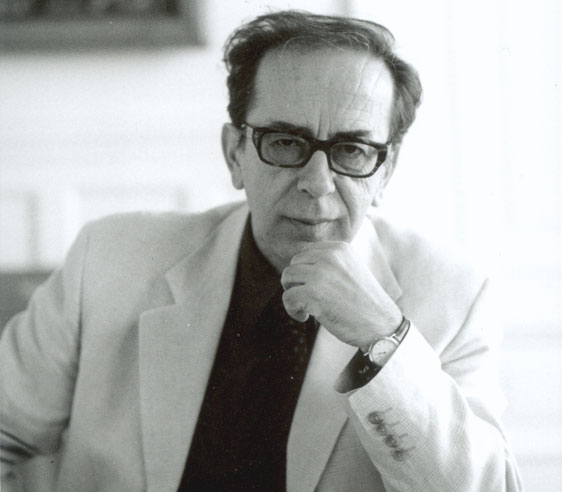

The strangest contradiction about Albania was that it was the home to one of the greatest of European writers of the epoch, Ismail Kadare, who would surely be a worthy recipient of the Nobel Prize (unlike some others who have recently received it). The puzzle is this: how is it possible that the most brutal and repressive of all European communist countries should nevertheless have tolerated such a writer, and even have allowed him to publish his books many of which were not merely unorthodox from the point of view of the official doctrine but clearly, albeit elliptically, opposed to it?

Could it be that the censors failed to understand the meaning of what he wrote? Hardly likely, since censors are not stupid just because they employed on a wrongful task on behalf of an evil regime. Their stupidity could not have lasted thirty years.

Could he have been used as a safety valve by the regime? This seems unlikely to me, for if nothing else the regime had the courage of its brutality and had had no compunction in shooting writers.

Could it have feared international reaction if it had imprisoned or executed Kadare? It is true that Kadare had become internationally celebrated in the 1970s, but a regime like Hoxha’s did not fear international opinion, for it could scarcely have been more internationally isolated than it already was. As, in its own eyes, the sole guardian of Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy left in the world, it might even had taken the world’s outrage as validation of the correctitude of its own action.

Was the relative freedom that Kadare enjoyed (only relative, I hasten to emphasise; he was the object of continual surveillance) a propaganda tool to demonstrate that Albania was not the tyranny everyone outside the country took it to be? Again, I do not think this likely, because the regime made no other efforts to prove such a thing. Its propaganda efforts were directed instead at something else, the supposed material and social progress it had made in Albania.

There remains a mystery about Kadare’s career, then, and about the man himself. In 1971, he joined the party and was for more than ten years a member of the country’s sham parliament. He left the country and claimed asylum in France only the year before the downfall of the regime, at a time when it must have been obvious that it was doomed and could not last long.

In 2006, he gave a long interview to Stéphane Courtois, the editor of The Black Book of Communism, a huge tome that gathered together all the crimes committed by communist regimes and movements around the world in the name of egalitarianism, a necessary book that confronted French and other European intellectuals with the ‘ideals’ to which they had for so long remained emotionally attached. (The book set off a vogue for similar ‘black books.’ exposing the crimes of various phenomena in the past, among them—to cite only those in my possession—colonialism, psychoanalysis and the French Revolution.)

Courtois touches, very lightly, on what seem to be paradoxes in Kadare’s career, for example, his adherence to the party. Kadare is obviously troubled by the question, and explains it as follows. His first passion in life had always been literature, and his only ambition to write. In a totalitarian regime, such a person is faced with a choice, either to compromise with the power or to remain silent. (Here I might add that, for many years, Kadare could not have left the country, neither if he had been able to do so could he have relied on a large enough Albanian-speaking diaspora to allow him to live by writing in Albanian.) Kadare chose compromise rather than silence, and membership of the party would give him some slight protection against the accusation that he was working towards the destruction of the regime as a ‘counter-revolutionary.’ He could get away with more implied criticism from within than from without; besides which, no less a figure that Enver Hoxha himself had suggested that he join the party, which was an invitation that it might have been ill-advised to refuse.

For years, Kadare played cat and mouse with the regime, coming not very far on occasion from a death sentence. Let him who has never had to face such dilemmas cast the first stone. Still, the demand for asylum so late in the day seems a little odd and might be taken by the suspicious as a flight not so much from the regime as from whatever was likely to come after it. The downfall of such regimes as Albania’s is often violent and vengeful: and Kadare’s life might have been interpreted by the Saint-Justs of post-communism as one of as much collaboration with, rather than of opposition to it, the better to hide their own complicity (it is one of the aims, or at least effects, of totalitarianism to implicate everyone in its crimes). Exactitude of justice, and the taking into account of circumstances, is not the first characteristics of the settling of accounts that occurs after the downfall of dictatorships, least of all after a dictatorship as horrific as Enver Hoxha’s, in which, according to some calculations, ten per cent of the population had experienced imprisonment, in terrible conditions even for prisons, at some time in their lives. Kadare says in the interview that, during his entire adult life in totalitarian Albania, there was never a time when he did not know someone who was in prison: and since such people continued to be tortured while they were in prison to betray others of their acquaintance, he always lived in fear of denunciation, a fear that lasted for decades.

His main fear though, he said, was that he would be prevented from writing. Cleverer than the regime, he managed to outmanoeuvre it, though it might well have gone the other way.

Courtois asked Kadare about the time he was obliged by the regime to pronounce an autocritique in front of high members of the party. It was sometimes claimed (usually by those who desired to minimise the criminality of communism) that such self-criticism was a mere formality, a kind of ritual to be gone through. Kadare says:

Self-criticism in communist regimes has nothing to do with conscience in the common meaning of the word. Nor with its purification, relief, or the slightest repentance. Such self-criticism is a tool designed to mutilate one’s being and obtain its submission. After a self-criticism, the person can never be again what he was. He remains handicapped. Like every recidivist, he can easily fall again. The immense legion of people who had been so marked was a legion of the sick.

Who, on reading this, could not think of the demands increasingly made on the academic staff of universities (and elsewhere) to adhere to doctrines with which they do not agree and which they know to be false? Once they have compromised with the demand, they can, in Kadare’s words, never be the same again. Their probity is destroyed once and for all, and they can easily lie again. They are henceforth mutilated, they become eunuchs. The people who demand the auto-mutilation may either believe in the supposed ultimate aim of the doctrine, or they may be mere careerists, but the end result is the same: lying as a means of survival.

Perhaps Enver Hoxha was right after all: for Albania has conquered the world.

Table of Contents

Theodore Dalrymple’s latest books are Neither Trumpets nor Violins (with Kenneth Francis and Samuel Hux) and Ramses: A Memoir from New English Review Press.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

3 Responses

It is terrible what the crowd will do to an individual.

There is one other element to take into consideration, which is not believable or understood by people from prominent countries like Italy, America, Britain etc. This will be incomprehensible to them.

In two-bit countries that have produced no famous international scientists, artists, athletes, performers and are, indeed, forgettable and worthless, the people become ecstatic if ONE person is talented enough to achieve international recognition. Britain, Spain, Russia, America have an embarrassment of riches, whereas ONE prominent individual in worthless countries is a source of intense national patriotism.

We saw this when Brazil became pre-eminent in soccer.

During the height of the Cold War, John Belushi, an Albanian, became famous as an actor in Hollywood (i.e., the world). Albanian newspaper gushed about him and the genius that was in every Albanian.

The ‘no’ in the following sentence should be deleted (or replaced with ‘any’):

“The fact is that no dictatorship, no matter how personalised or totalitarian it may appear to be, relies on a cadre of servitors; and these servitors have much to fear from a real change of regime, for they have been the accomplices, often more than willing, of its crimes. “