by J.A. Marzán (September 2016)

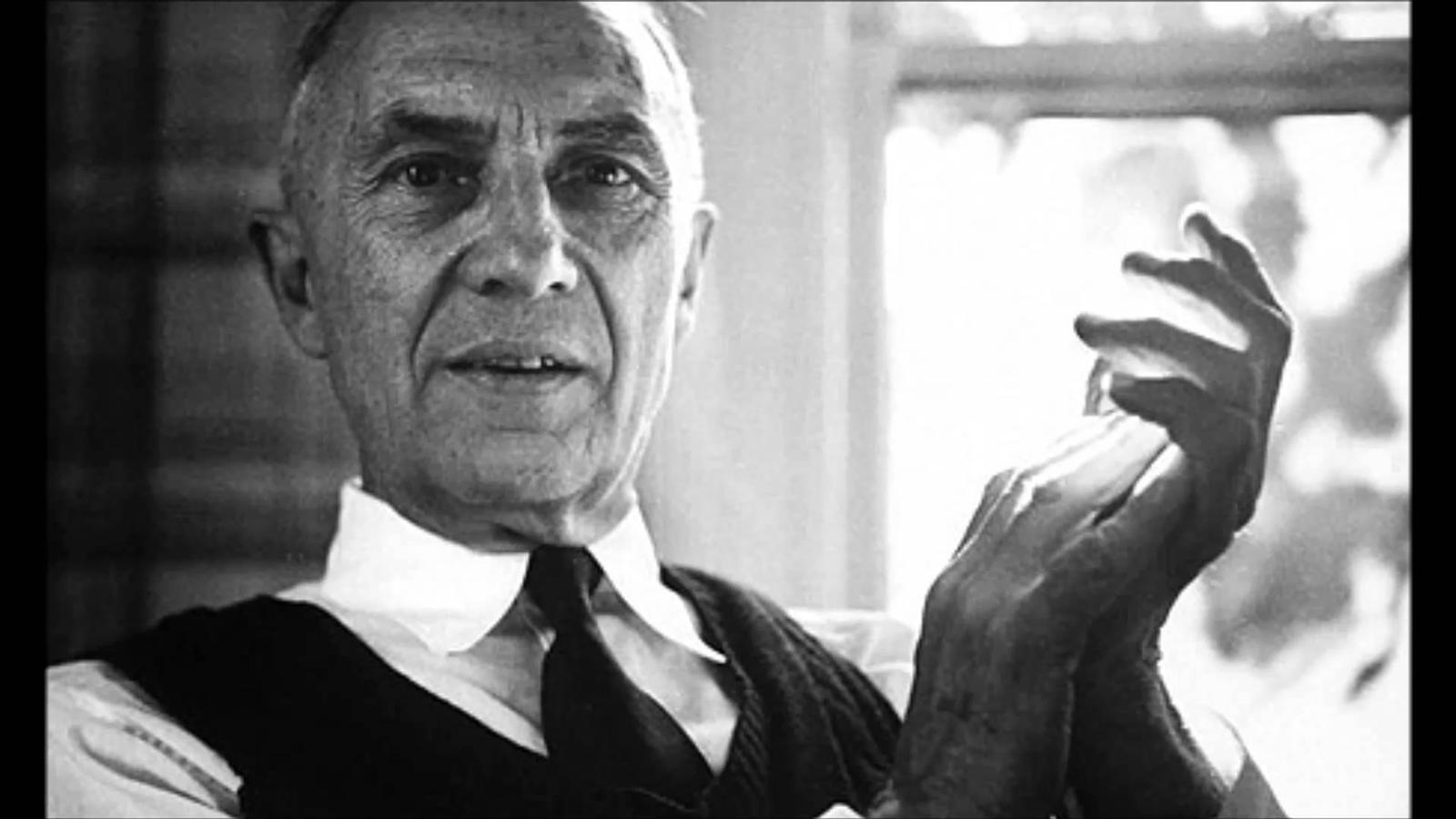

William Carlos Williams

This year, in which Lin-Manuel Miranda won the Pulitzer Prize and his musical Hamilton 11 Tonys, is also the eve of the centennial of Al Que Quiere (1917), the first important poetry book by William Carlos Williams, who in 1963 was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer for Pictures from Breughal and Other Poems (1962). Less known as playwright, through his mother Williams was of Puerto Rican descent, like Miranda, a shared lineage that explains Miranda’s invoking in Hamilton Williams as literary antecedent–if not consciously and not the New Jersey poet and playwright usually read in college but the bicultural Williams I introduced in my The Spanish American Roots of William Carlos Williams.

Williams’ mother Elena Hoheb Williams was born under the Spanish flag in Puerto Rico. His father was born in England but from the age of five grew up in the Caribbean a Hispanophile, preferring Spanish-speaking at home. Both parents gave him a Hispanic background, with the stronger intellectual influence ironically from his English-born dad, whose readings of Spanish classics to his son affixed the baroque Góngora and Quevedo on his son’s mental bookshelf next to Shakespeare.

This ingrained admiration for his Spanish literary heritage complicated Williams’ complying with the ritualistic shedding of his immigrant parents’ culture. His challenge, epitomized in Ezra Pound’s dig that he was a “foreigner,” only juiced his resolve to prove that not despite but because of the Carlos in his name as poet he embodied a truer American legacy than Pound and H.D.

In the American Grain (1925) reminded Americans that his Spanish forebears arrived a century before the English and came to “lay hands” on and baptize the Indian, whom they also married, whereas the “squeamish” Puritans came not to “touch” the native and in every sense never to truly marry America. An inclusive spirit was the litmus test that he applied in revisiting American history, why he identified with the robust, amorous human under the preserved stone monument of George Washington, about whom he wrote a three-act libretto for a grand opera. Prefiguring Hamilton, The First President, was intended to “galvanize us into a realization of what we are today.” Published in 1936, it was never produced.

In 1950, three years before Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, Williams compared the McCarthy hearings to the Salem witch trials in his verse play Tituba’s Children. The play’s setting alternates between the then-present in Washington and the New England colonial past, in which Tituba, a slave woman from the West Indies, is charged with introducing witchcraft to children. Williams again uses history to make us rethink the present, but not limited to the hysterical injustice of the hearings and foreshadowing Miranda.

Tituba’s trial was also a metaphor of Williams’ mother Elena’s trials with xenophobic, late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century America. Via a racially murky Dutch and West Indian lineage, she embodied Williams’ idea of the Caribbean as matrix of the most authentic American “mingling” spirit, which as he received from his mother the nation inherited as Tituba’s children. (Answering doubts of Carlos at work: the play’s eight-syllable verses imitate the style of the Spanish baroque.)

Lin-Manuel Miranda identified a Caribbean lineage in Alexander Hamilton, a bastard son from the island of Nevis, discovering Williams’ idea of the truly American-spirited in the first treasurer’s social impurity–in the line of Tituba and Elena. Miranda also invokes Williams in carrying out their patently shared dictum that a writer better confronts the threat of marginalization not with testimonial but with art. As Williams broke up the rigidity of the American imagination with Modernist poetry also as personal liberation from traditional American ethnocentricism, Miranda rewrites the Revolution both in music that braids tradition and hiphop and in recasting non-Hispanic white men as black and Hispanic players. “Our cast looks like America looks now,” he said to the Times’ Michael Paulson. “It’s a way of pulling you into the story and allowing you to leave whatever cultural baggage you have about the founding fathers at the door.”

That baggage is the traditional American Story, the simpler monocultural enchantment that has historically bulwarked the nation from its more complicated multicultural history. Not seeing himself in the country of that Story, in Hamilton’s closing number ‘‘Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story,” Miranda echoes Williams in reminding us that ultimately this nation is a narrative that, to be truly American, has to be properly told. Hamilton has just staged what almost a century before Williams performed in the essays of In the American Grain, among them an appreciation of a genuinely American-spirited Washington, which evolved into an opera.

Today Miranda exercises the multicultural freedom to be American and still see Puerto Rico as cultural “home,” as he expressed while visiting there. He also recently appealed to Congress, on HBO’s Last Week Tonight, to help out the island’s struggling economy. Williams, in contrast, having augured Miranda’s multicultural consciousness, didn’t have today’s latitude and necessarily subdued his biculturalism by dignifying with more formal posturings: at a time that predated Latin America’s emergence, Puerto Rico symbolized his Spanish literary heritage, and he ostensibly remained aloof from the post-WWII migration that delivered the parents of Miranda.

I say ostensibly because Williams, whose writing career was determined by his conflicted loyalty to parents who declined to become citizens, ineluctably had to have contemplated those newcomers who ironically arrived from Elena’s island as naturalized American citizens. Personally and socially he dissociated himself from their drama, but not as writer and not from its metaphors.

In the years that West Side Story ran on Broadway, an obviously germane theatrical event given no importance in his writings, and five years after his mother’s death, he accepted an invitation to read in her hometown Mayagüez.

While there he gathered material for the book about her that he had promised to write decades earlier. Yes, Mrs. Williams was published in 1959–the year of the film version of West Side Story and seven years after her death, when no one would have otherwise associated her with that migration. Williams being Williams, this celebration of Elena as a pure product of the Caribbean and specifically Puerto Rico also elevates her to a metaphor of spontaneous creativity in language, his maternal Kore.

The ostensible and the actual kept Williams’ two psyches in stasis. Carlos was his creative and sexual duende, encoded in tropes, baroque wordplay; Bill was his straightforward public speaker, his puritanical ballast, uptight when addressed as Carlos. With trepidation Bill welcomed his visiting acolyte, the American-spirited, pot-smoking Beat Allen Ginsberg–who didn’t know that he really had come to visit Carlos.

But affirming Jorge Luis Borge’s aphorism that, whether or not consciously, every writer creates antecedents, now Miranda knocks on his door as a bro. The canonical Bill stiffens but Carlos has already pollinated the American consciousness with the inclusive, “mingling” spirit that Miranda harnesses in his musical seance Hamilton. Their meeting, a dividend of diversity and immigration, is a gift outright to the nation from their Puerto Rican origins.

________________________________

J.A. Marzán is a poet and novelist. His most recent book is the paperback edition of his novel The Bonjour Gene. The influence of his work on Williams is evident in the introduction to the forthcoming centennial edition of Al Que Quiere (New Directions, 1917) and in The Cambridge Companion to William Carlos Williams (2016), which contains his essay “Reading Carlos: Baroque as Straight Ahead.”

To comment on this essay, please click here.

To help New English Review continue to publish interesting and insightful essays such as this, please click here.

If you have enjoyed this essay and want to read more by J. A. Marzán, please click here.

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link