Linda Nochlin and The Imaginary Orient

by Ibn Warraq (June 2010)

Of this painting, Lisa Small of the Dahesh Museum wrote, “This particular image combines Gérôme’s two great themes, Orientalism and history, depicting a somber Napoléon retreating from Acre. As [Earl] Shinn [ 1837-1886, editor of one hundred photogravures of Gérôme’s paintings in ten volumes] describes it, the emperor, mounted on his ungainly beast of burden, in this burning and dreary march…with his discontented and defeated army around…experiences, for the first time, the bitterness of disappointed ambition.”[3]

Several points need to be made. First, history was one of Gérôme’s important themes. Second, the subject is Napoléon’s defeat; there is no colonial or imperialistic triumphalism. Many Orientalist painters tackled historical subjects, especially the presence of the French in the Near East and North Africa, though Nochlin insists that the French are always “absent.” Phillipe Julian’s excellent survey defines Orientalism as “a form of Romanticism just as it is a new way of painting history, with which it is often closely linked. The artists found fresh inspiration in political events. Between 1820 and 1830, the independence of Egypt, the liberation of Greece, and the conquest of Algeria brought the Near East and the Middle East into the mainstream of European affairs.”[5]

The

“Indeed,” continues Nochlin, “it might be said that one of the defining features of Orientalist painting is its dependence for its very existence on a presence that is always an absence: the Western colonial or touristic presence.”

If you have ever visited the Taj Mahal, the seventeenth-century Moghul masterpiece in Agra, you have not resisted the temptation to take a photograph of it. If you have taken a photograph, you were anxious not to include some fat Western tourist, in shorts, hat, and sunglasses, with a camera slung ’round his neck, in the frame. You waited until there were no tourists near to spoil the view; such tourists would have looked out of place and as inapproriate as their dress. Orientalist paintings were often commissioned by Europeans or Americans back home, and the latter certainly did not want to buy views that showed tourists. Evidence of this comes from the books of two very gifted modern Indian photographers, Raghu Rai and Raghubir Singh. No Western tourists disfigure their photos. In Raghu Rai’s photo portrait of Calcutta,click here.

Raghu Rai’s book of photographs of the Taj Mahal is pure Orientalism, using this term in a non-pejorative sense. Taken in the 1980s, his photos have a remarkable affinity to the work of the Orientalist painters of the nineteenth century. One shows what may be a camel skeleton lying in a river bed, bearing an uncanny resemblance to Gustave Guillaumet’s Le Sahara in the Musée d’Orsay. There are striking images of decaying monuments, Indian women in colourful traditional costumes, naked children playing on dirt roads, and women carrying copper or metal vessels on their heads.[8]

[10]in sight.

One can imagine what Nochlin’s criticism of an Orientalist work that did show a European in one of their paintings would be: “Of course, Gérôme would have to put in a European to remind us that it is really the European who is the master; there is no space that belongs to the Oriental, it has all been usurped by the colonialist. The Oriental cannot be left alone even in his own home…..”

Nochlin complains of Gérôme’s technique: it is too smooth, she thinks he is trying to hide his art. But Gérôme is famous precisely for his meticulous finish; it is a style of painting shared by other great painters, such as Ingres, with his superb draughtsmanship and precise Neo-Classical linear style, and without thick impasto. As Delacroix put it, “…the sight of a few Ruysdaels, especially a snow effect and a very simple marine where one sees no more than the sea in dull weather, with one or two boats, appeared to me the climax of art, because the art in it is completely concealed. That astounding simplicity…..”[12]

In any case, Gérôme’s technique was not followed or copied by all Orientalists. Some were even close to the Impressionists in their style, such Félix Ziem; some Impressionists, in the strict sense, such as Degas, Renoir, and Manet, also painted scenes from the Orient.

Nochlin complains about “a plethora of authenticating details,” especially the “unnecessary ones.” Orientalists are accused of painting an imaginary Orient, and then also accused of “insisting on authenticating details. One cannot have it both ways. Should they have left out the authenticating details? Would that have improved the paintings? And would not these details help dispel the mystery that seems to vex Ms. Nochlin? Surely it is the artist’s prerogative to decide which details are necessary and which not.

“Neglected, ill-repaired architecture functions, in nineteenth-century Orientalist art, as a standard topos for commenting on the corruption of contemporary Islamic society.” Has Nochlin ever been to the Orient? It is her Orient that seems to be imaginary. Even now, one of the most distressing sights, at least for me as someone originally from India, is the physical decay of so many beautiful historical palaces and monuments in contemporary India. It was even worse in the nineteenth century, until a British Viceroy, Lord Curzon, did something about it. The situation was, and is, similar in North Africa, Syria, Egypt, and other Islamic lands. The Orientalists painted what they saw. It is true that ruins do attract the Romantic mind, and have been popular at least since the ruins of ancient Rome were painted by Hubert Robert [1733-1808]. But delight in ruins is an aesthetic attitude, not a political statement.

New York Times journalist Alan Cowell wrote in 1989 that Cairo “oozes decay.”[15]

And, it is well-attested that tiles in Turkish mosques often fell off simply because of the poor quality of the glue used.

Nochlin complains that there are too many lazy natives in Orientalist paintings, not enough people doing their jobs, not enough activity. But she cannot have looked carefully. There is a rich-toned work by Rudolf Ernst in the Dahesh Museum of two men in their workshop, beating into shape copper objects; Charles Wilda’s A Coppersmith, Cairo [1884]; E. Aubry Hunt’s The Farrier, TangiersView of Constantinople of 1870, now in the museum in Nantes; Albert Pasini’s Bazar at ConstantinopleMarket Scene in CairoBarbers Working in a Square in Constantinople. Then there are busy port scenes in numerous paintings such as Carlo Bossoli’s Oriental Port. Dervishes are often portrayed, and they are hardly inactive. There are also paintings of hunting with falcons, guns, on horseback, and so on, as in the works of Eugene Fromentin. And what of the exhilarating sense of movement in Giulio Rosati’s Successful Raiding Expedition?[17]

.jpg)

View of Constantinople by Germain-Fabius Brest

[18]

Nochlin lets fly one baseless charge after another. One wonders if she has bothered to really look at, let alone enjoy, a work of Orientalist art. Here are her final thoughts on Orientalist art: “Works like Gérôme’s, and that of other Orientalists of his ilk, are valuable and well worth investigating not because they share the esthetic values of great art on a slightly lower level, but because as visual imagery they anticipate and predict the qualities of incipient mass culture. As such, their strategies of concealment lend themselves admirably to the critical methodologies, the deconstructive techniques now employed by the best film historians, or by sociologists of advertising imagery or analysis of visual propaganda, rather than those of mainstream art history.” Evidently, for Ms. Nochlin and her ilk, Orientalist art, as John MacKenzie pointed out, “exists on an entirely different plane from that considered by ‘mainstream art history.'”[20]

Orientalist art must be seen as a continuation of those aesthetic impulses that began at the dawn of Western painting. Many Orientalist painters and sculptors were motivated by the same artistic desires as those of the Renaissance. Gentile Bellini, Carpaccio and other Venetians, but also Rembrandt and the Flemish Pierre Coeck d’Alost, have been mentioned. Nochlin seems irritated by Gérôme’s Arabic calligraphy, but in fact, a little “mainstream art history” would reveal that from the late thirteenth century onward, Western artists were fascinated by Oriental scripts and used it in many of their works. Many artists, not knowing Oriental languages or scripts, invented pseudo-scripts for decorative purposes and used them on textiles, gilt halos, and frames for religious images: artists such as Duccio, Giotto, Fra Angelico, Andrea Mantegna, Gentile da Fabriano, and so on.

Artistic concerns were paramount: “Artistic concerns also played an important role in the various adaptations of Arabic writing and the Islamic objects on which such writing appeared. Giotto and his contemporaries developed an immediately recognizable version of the Eastern honorific garment to make their representations more vivid and, and in their view, more accurate. The imitation writing on halos and frames was ornamentally sophisticated, consistent with the Eastern garments, and perhaps also emphasized that these were images of a universal faith.”

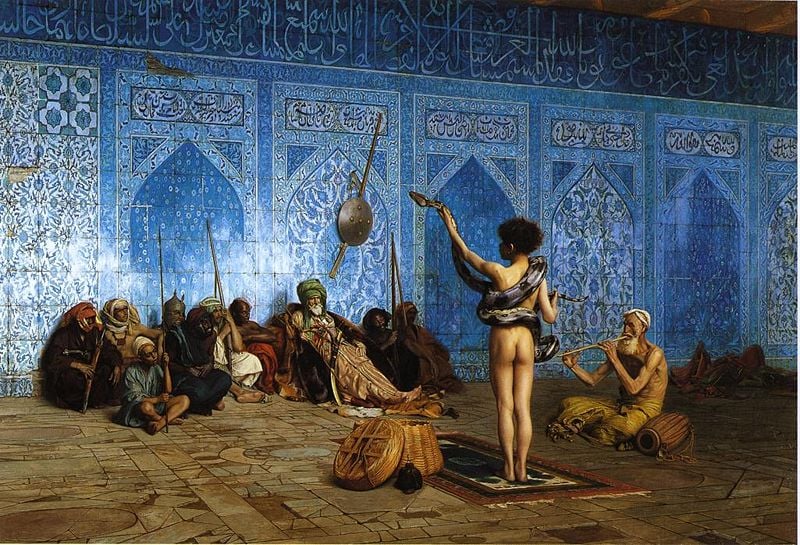

Gérôme and other Orientalists were more successful in rendering Arabic script; they also admired the aesthetic qualities of Arabic calligraphy. Referring to the Arabic inscriptions in Gérôme’s Snake Charmer, Nochlin quotes Ettinghausen, a great scholar and expert on Islamic Art, as saying that they could “be easily read.” Then Nochlin adds a contradictory footnote: “Edward Said has pointed out to me in conversation that most of the so-called writing on the back wall of the Snake Charmer is in fact unreadable.” Pace Said, the large frieze at the top of the painting, running from right to left, is perfectly legible. It is the famous verse 256 from Surah II, al-Baqara, The Cow, written in thuluth script, and reads,

There is no compulsion in religion—the right way is indeed clearly distinct from error. So whoever disbelieves in the devil and believes in Allah, he indeed lays hold on the firmest handle which shall never break. And Allah is Hearing, Knowing

Unfortunately, the inscription thereafter is truncated, so that the upper part is lost, but even then one can make out parts of it, probably not a Koranic verse but rather a dedication to a caliph; the name Uthman is just visible, and possibly the word Sultan. The Turkish artists and architects often added a dedication in mosques, and even on coats-of-arms, such inscriptions as, “The ruler of the Ottoman Empire, Sultan Abdülhamit who puts his trust in God.” Or was Gérôme simply copying faithfully a real wall with those very verses? I have learned from Professor Gerald Ackerman that Gérôme executed the painting in his Paris studio, copying a photo from the Topkapi Palace published by Abdullah Frères, the Istanbul photography firm. This discovery makes Nochlin’s remarks even further off the mark.

Many copper vessels, plates, and weapons decorated with silver and gold and produced in Egypt, Turkey, or Morocco, both contemporary and those manufactured a hundred years ago, show what purport to be Arabic scripts or inscriptions, but in fact are gibberish, since the artisan producing such objects is often illiterate, certainly ignorant of Classical Arabic, and the complex rules of Arabic calligraphy.[23]

Let me summarize: Does the frieze represent actual writing? The answer is yes. Is the writing in any sense legible? Here again, the answer is yes. It is not easily legible, but nor are all the stylized inscriptions in, for instance, the Dome of the Rock. It is simply a feature of Islamic calligraphic art, and in this case Gérôme was not inventing the writing. But even if Gérôme had invented the inscriptions, what conclusion would follow? Only that Gérôme did not know Arabic. But neither does Nochlin. If Gérôme’s ignorance of Arabic is an obstacle to painting about the Orient, why isn’t Nochlin’s ignorance of Arabic (or Turkish) an obstacle to writing about Orientalism in art?

There were at least four hundred Orientalist artists of stature

To comment on this article, please click here.

here.

If you have enjoyed this article by Ibn Warraq and would like to read more, please click here.