Loneliness

by T. E. Creus (April 2021)

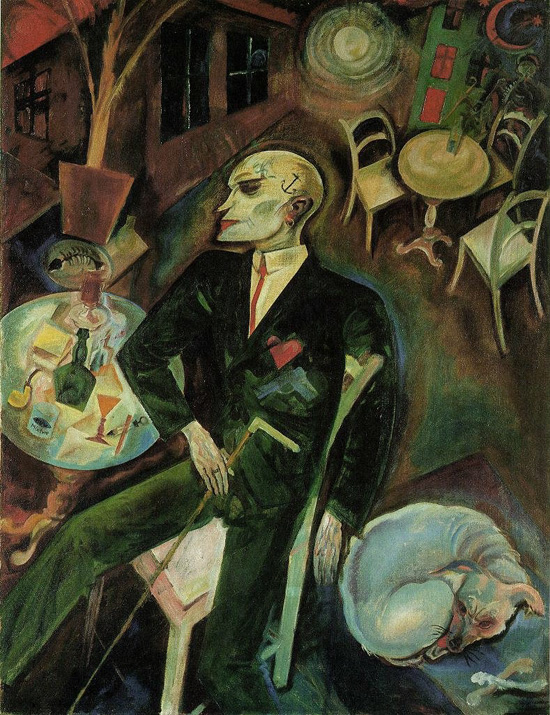

Der liebeskranke Mann, George Grosz, 1916

The man was sitting alone in a stool by the bar, drinking his fifth or sixth pint of beer. He seemed to be in his forties, or perhaps he was in his late thirties but he looked a bit older on account of his constant abuse of alcohol. He was wearing a dark leather jacket that had clearly seen better times.

Since he had no one sitting next to him and the place was quite empty, as it was very late, he was talking to the bartender, who could not get away and had to pretend to be interested, even though he probably was just counting the minutes to closing time.

“That bitch,” said the man, with that whiny tone typical of drunks who tend too much towards self-pity. “She took my money and the kids. I can’t even see them anymore. She put a restraining order on me, can you believe it? Accusing me of this and that. All lies. She hates me. She really hates me. I don’t even know why.”

“Right,” said the barman, who had heard that same story, from so many people, so many times.

“I miss the kids. I really miss them. I even miss her, you know? Ha-ha. I miss the bitch. And you know, I haven’t dated anyone in five years. Five years. Ever since the divorce. I haven’t been with anyone. Of course, who would date a loser like me? Haven’t even been able to keep a job after all that. I’m poor now. But I don’t mind the money, you know. Or losing the house. It the loneliness, man. It’s the loneliness that gets you in the end.”

“Ha!” said a voice in the back. He turned around with surprise and saw an old man sitting by himself in a table in a dark corner. He hadn’t noticed him before. It was the only other person in the pub. “Loneliness? What do you know ‘bout loneliness? Nothin’! You don’t know what real loneliness feels like.”

The old man spoke with a strange foreign accent that he couldn’t quite place; maybe Russian, maybe Eastern European.

“And who are you?” asked the man, getting up and walking, or rather stumbling towards the old geezer in the back of the room.

“No, don’t come any closer. I advise this for your own health. Just stay where you are. You can hear me well enough from there.”

The man stopped, unsure of what the old man was up to. He retraced his steps and sat down again, but kept looking back at the old man with derision.

“I’ll tell you what loneliness is,” said the old man. He picked up a vodka bottle from the shelf behind him and poured it up to the brim. He turned towards the barman, “Put it on the tab, Jack.” Then after drinking a full glass, he turned again to the man in the stool.

“I was born in Minsk. That is Belarus today, but it was in the Soviet Union at the time. My childhood was happy, and, I suppose, normal, or as normal as they could be under the circumstances. But when I turned thirteen,” and here he poured himself another glass. “When I turned thirteen is when trouble started.”

“My parents were university teachers; a somewhat dangerous profession at the time. My father published an academic article that had very little to do with politics but was considered contrary to the regime by the authorities, for some reason or other; perhaps it merely mentioned some historical character that had been popular years earlier with the former bureaucrats but fell out of favour when a new generation of Soviet politicians took their place. Or perhaps what had happened is that someone else at the university, envious of his father’s position, had denounced him with false accusations. I don’t know; things like that happened very often at that time. So after a trial, if you could call that farce a trial, he was condemned to the gulag. Ten years of forced labour, and not only him, but the whole family. Not all together, tough. My dad and I would be taken to a prisoner male camp, and my mother would be separated from us and taken to a female camp. My parents couldn’t accept that separation; and so, when we had just arrived at the prisoner triage centre, they tried to escape from the guards, taking me with them, of course. But I was little more than a child then; I couldn’t run very fast. We were easily captured again. And then my mom and my dad were shot.

“They left me alive for some reason. I was almost fourteen, I guess they figured there were still things to do and I was old enough to work. And so I stayed there in the gulag. Carrying stones, cutting timber, all kinds of work. Backbreaking work, I tell you. I never worked as hard in my life. That lasted for two, or maybe three years.

“But at some point people started to get sick. Typhus. First the prisoners, then the guards. That winter there had been an avalanche in the region, so transport and communication lines were all cut, and no one could call for help. In the end, they all died, prisoners and guards alike. I was the only one who remained alive.

“Some weeks, or maybe a month later, a group of soldiers came to inspect the camp and bury the corpses. They closed the camp; they had other larger gulags now, there was no point in keeping that small one active. I hid in the bushes so they could not see me and take me away.

“I was lucky that they forgot, or didn’t care enough, to take all the blankets and food reserves and medical supplies from the camp with them. Maybe they were afraid of catching typhus. They just left everything as it was. So there was a lot of canned food that remained there, and I could live on that for a few months. I also learned to hunt small game with a slingshot, and later a bow and arrow, that I made myself. Birds or squirrels if I was lucky. If I was unlucky, lizards and rats. I also learned to recognize the herbs and fruits that I could eat, and those that I could not. After much vomiting and diarrhoea, I learned pretty fast.

“I stayed there for several years. I don’t know how many, I didn’t count. Maybe fifteen. In total solitude. You see, I was afraid that they would arrest me again if I tried to go back to civilization. So I just stayed there. What else could I do?

“But one day, I was your age maybe, or maybe a bit younger, but not so much. I suppose about thirty-something. Anyway, I was watching some birds in a nest, and there was this mama bird feeding their baby birds. And I thought, not even animals are alone. Birds live with other birds, bears live with other bears, wolves live with other wolves. So I decided to risk it. I couldn’t take that lonely life anymore. And so I decided to walk away from the camp, and try to get back to society.

“But it wasn’t easy. That camp was really far from everywhere. There was only forest and mountains around. I started walking in the spring; it was almost the end of summer when I arrived finally at a place that looked like some kind of town.

“I was ready to meet other humans; I didn’t even care if they ended up being soldiers or soviet officials who could arrest me, I just wanted to see human faces again, and hear human voices, and touch human skin.

“But the town was empty. The whole town, do you understand? Houses, shops, offices. It was as if people had just abandoned it. I thought, maybe the world ended, maybe third world war happened, and I am the only survivor? I didn’t understand what had happened at all. Even when later I saw a sign with the name of the city, Chernobyl, I didn’t understand. You see, I did not have access to newspapers, radio, anything, for fifteen years. I had no idea what was going on in the world.

“It was starting to get cold, so I ended up spending the winter in that city. People had left food and clothes in their homes, as if they had to run away in a hurry. An invasion? A disease? It didn’t matter. Whatever had been the danger that caused people to escape, it was obviously no longer present, and I had a warm place to stay, with food and clothes, so I waited out the winter there.

“Then, when it was spring again, I resumed walking. I needed to see at least another town, you understand, if only to make sure if I was or wasn’t the only person left in the world. So I walked and walked. I walked through forests and two small ghostly villages, also empty. I was starting to lose hope, until one day I saw a barrier far away, and some military trucks parked at the end of the trail. I was so happy to see that there were people, living people, in the trucks! Soldiers, of course. But I didn’t care. It was the first sign of human life I was seeing in fifteen years, or twenty! Little did I know that my nightmare was only starting, that all I had lived until then had been only a prelude to a veritable symphony of horror.

“I walked towards the soldiers. I waved at them. “Hello!” I called. I thought they would arrest me. But no; actually, the strange thing was, that they seemed to be somewhat scared. Scared of me! They told me not to get any closer. They called someone on their radio transmitters. Then an ambulance came and I was taken to a hospital or lab somewhere.

“I was interrogated for hours. I told my story again and again; they didn’t believe me. I was kept in isolation in a chamber behind metal doors. They said there had been an accident at a nuclear reactor in the region. That was why the region was empty and entrance to the whole zone had been barred. They said that I was radioactive: the Geiger counter went crazy when they pointed it at me. They said, with my levels, I should be dead. But I wasn’t, and they couldn’t understand why.

“I was taken to the installations of Dr. Zabludovsky. I never forgot that name, nor that face. A vulture-like face: bald, with tiny eyes and a long nose. He was ugly and evil, and his nurses and assistants were perhaps even worse. I was submitted to hundreds of horrible, inhuman experiments. I don’t know what they wanted, I suppose they were trying to understand how I could be so radioactive and still remain alive. I had no cancer, no diseases, nothing. Well, until I was in their hands, that is. Under that demonic doctor’s guidance, I was injected with all kinds of substances, suffered all kinds of surgeries and blood transfusions, was electrocuted, measured, x-rayed, photographed. Some of the experiments were quite painful. Some of the medicaments they gave me made me sick. I begged them to stop, I cried for mercy, but it was useless. And when no experiments were happening, I had to stay in isolation inside a lead-covered chamber. Completely in the dark.

“It was on one of those nights that I prayed, for the first time in maybe twenty years. It was my mother who had taught me how to pray. She was an Orthodox Christian; even though the religion was officially forbidden by the regime and we couldn’t go to the mass, she would teach me to pray, and used to read out loud for me every Sunday a few pages from the Bible. So there, in the dark, desperate for help, for any kind of help, natural or supernatural, I prayed.

“And I don’t know if it was because of the prayer, or for some other reason, but eventually things started to change.

“I was tortured for months, maybe a year. But I had my revenge. They all started to get sick or die, from different forms of cancer. First a nurse, then an assistant, then finally Dr. Zabludovsky himself. Apparently I could contaminate other people with radiation, but it didn’t affect my own body somehow. I had become some kind of radioactive Typhoid Mary, an asymptomatic carrier of radiation. Go figure. The fact is that they were all scared of me after that, nobody wanted to get close to make any experiments, and eventually I managed to escape.

“Roughly at that same time, the Soviet Union was crumbling. The Berlin Wall fell, the whole communist world fell, almost in an instant. It was a chaotic time; I managed to buy from a gypsy merchant some false travel documents and use them to emigrate. I came to America. Lots of people from former communist countries were being allowed in at the time as asylum seekers. So I came too.

“But I couldn’t live a normal live. I couldn’t marry; I couldn’t fall in love; I couldn’t even have friends. See, I had this curse. Imagine that I fell in love and married someone, and had kids, and then, because of me, she ended up with cancer and then dying, and then the kids ended up dying too. Do you see? The idea that I would bring death to anyone I cared for, just by being close to them, was unbearable.

“So I avoided people as much as I could. I found a job as a night guard at a museum; the place was always empty during my shift, and I had very little contact with other employees, so it was an ideal position for me. Other than the job, I stayed mostly at home, and avoided meeting anyone.

“There was a woman once. A neighbour. She was beautiful, blonde; I used to watch her everyday as she walked out and then took the bus to go to work. Sometimes I watched her standing at her window, looking out. Sometimes I waited outside as she left her door, just to see her a bit better. Once, she waved at me and smiled. “Hello”, she said. I smiled back, from a distance of at least twenty meters. That was the closest I ever got to love.”

The old man sighed at this point. He reached for the bottle and poured himself another drink. “So, don’t talk to me about loneliness,” he said. “You don’t know what the hell you’re talking about.” Then he emptied his glass, and didn’t say anything else.

The man in the stool remained silent for several minutes, looking with awe at the old man. The story had sobered him up, and it was becoming late. He paid for his pints and got up. He also handed the barman a couple of twenty-dollar bills. “For the old man’s tab,” he said. He hadn’t asked his name.

He didn’t know if the story of the old man was true or a drunkard’s tall tale, but he had seemed sincere, even emotional as he told it. Just in case, he decided not to get too close to him; he just thanked him and waved from the distance, then left the seedy pub.

As he walked home he saw other drunks, coming from many other bars and pubs, slowly going back to their houses; some back to their wives or families, some to their lovers; others, like himself, back to a bachelor apartment somewhere. Regardless, they all seemed sad and lonely. Even those who had a wife or a family perhaps dreaded going back home, or they wouldn’t be out so late at night. At least that’s what it seemed from their expressions, from their slow and unwilling gait. But he was thinking about the old man’s story, and felt that, in many ways, he could consider himself lucky. The old man was right. He didn’t really know what true loneliness was like. The night was cold and he didn’t feel like walking, he thought about the frozen Russian forests that the old man had traversed alone, so he stopped a cab and went back home to sleep.

__________________________________

T. E. Creus is the author of Our Pets and Us: The Evolution of Our Relationship and the collection of short stories The Sphere. More info at his site contrarium.org

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast