by Terry Dunford (June 2011)

The critical literature on The Americans may be summarized as follows: the book is appreciated as long as it is viewed as a polemic rebuking American culture of the 1950s.

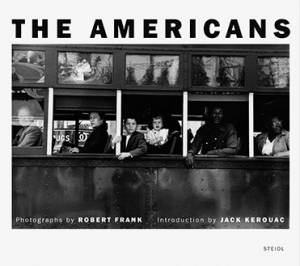

As 2009 was the fiftieth anniversary of Robert Frank’s chef-d’oeuvre, The Americans, Frank was honored with a retrospective at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Looking In: Robert Frank’s The Americans,” September 22, 2009–January 3, 2010, and an accompanying 500 page catalogue raisonné published by the National Gallery of Art. How’s that for validation?

First published in France as Les Américains (and hence the literal translation of the title into English unnecessarily retaining the definite article), The Americans contain some 83 black and white photographs chosen from a storehouse of photographs that Frank took as he traveled across the United States in 1954 through 1956 or so.

In the style not unlike the “street photography” of Henri Cartier-Bresson or closer to home Frank’s contemporaries, Rudy Burckhardt (like Frank, born in Switzerland), Louis Faurer and Vivian Cherry, Frank captures people working, eating, waiting for a bus, selecting a tune on a juke box, or watching a parade.

So why is The Americans afforded an exhibition at the Met (not to mention a recent documentary film, An American Journey: Revisiting Robert Frank’s ‘The Americans’)? What is it about The Americans that garners universal praised by academics and art critics? The answer, unhappily, has little to do with Frank’s art. Reading the literature on The Americans it is more than apparent that The Americans is appreciated as long as it is viewed as a polemic. There is an algorithm embedded in the minds of the literati that descriptions of American in the 1950s may only be done in caricature. If you do not agree that the ethos of the ‘Fifties is to be ridiculed and reviled, you are not a serious person. When we are told that Frank “exploded national myths and punctured the bland optimism of Eisenhower’s America,”[i] we are asked to accept a characterization of an era that is both popular and unproven. The Americans receives high marks from those who reduce the book to a jeremiad, a rebuke to an America, doomed to “ennui and alienation in the Eisenhower years, an era generally characterized as a high point of American complacency, hypocrisy, and superficiality,”[ii] Setting aside the fact that this characterization is a tad simplistic, the assumption that The Americans is contemptuous of its subject matter is all but the received opinion among Robert Frank’s admirers, repeated in tedious unison, echoing the same phrases and generalizations that tell us nothing of Frank’s art. Most of Frank’s admirers have this in common: bold assertions, little analysis, and no evidence. For example, without reference to any of the photographs in The Americans, an art critic writes that Frank’s book “depicted some of the same trends identified by David Riesman in his book, The Lonely Crowd. . .”[iii] Still another critic finds in The Americans a “sense of alienation, emptiness, and ennui of the kind discussed by Riesman in his sociological study of the 1950s, The Lonely Crowd.” [iv] Not to be outdone, yet another critic asserts that “Frank depicted America as a society with a deep-rooted sense of psychological isolation, what sociologist David Riesman called ‘the lonely crowd.’”[v] Reading commentary on The Americans is akin to reading menus from a dozen Chinese restaurants. They all sound the same. (And by the way, how can The Lonely Crowd be a “sociological study of the 1950s” when Riesman [and Nathan Glazer and Reuel Denney] wrote their book in 1949?)

A 1985 article on The Americans is so far off the mark it is necessary to read the offending passage at length:

At the time of publication, attention was focused primarily on the book’s iconography, specifically upon its doggedly downbeat tone. Frank dealt with a United States that Middle America preferred to ignore, particularly during the comfortable, prosperous Eisenhower years. Frank showed a seedy, grey America, the dark underbelly, populated by isolated, alienated people – hat-check girls, waitresses, truckers, midnight cowboys, ‘niggers,’ and ‘commie queers.’ He showed a landscape of desolation, that seemed to consist entirely of highway detritus, dingy diners, decrepit automobiles, and greasy gas stations, lit perpetually by the cold drizzle of an unfriendly dawn – an America, in short, filtered out of most Americans’ consciousness, despite its ubiquity.[vi]

We have come to expect yet another reflexive sneer at the Eisenhower years among the predictable conclusions, but here even the facts are wrong. There are no hat-check girls in The Americans. No truck drivers. No “midnight cowboys” (whatever that anachronism may mean). Far from being decrepit, the automobiles pictured in The Americans are mostly of recent vintage,[vii] and one is a futuristic concept car (“Motorama – Los Angeles”). The “dingy diners” are, in fact, uniformly bright and sparkling clean.[viii] But worst of all (worse even than the pretentious Kerouacian diction: the “cold drizzle of an unfriendly dawn,” indeed) is his ability to attribute (without reason) to contemporary viewers of The Americans such terms as “ ‘niggers’ ” and “ ‘commie queers,’ ” because, presumably, from a morally superior 1985 perspective, those ugly words would be typical descriptions of blacks and gays in the 1950s.

Reading the commentary on The Americans, one must wonder: has anyone looked at the photographs?

If all you knew of The Americans came from academic accounts, you would expect images of white-only drinking fountains and snarling police dogs. Without citing a single Frank photograph to illustrate her point, Sarah Greenough, Curator of photographs at the National Gallery of Art, asserts that The Americans “. . . speaks of the profound malaise of the American people during the 1950s. It reveals the deep-seated violence and racism, and the mind-numbing roteness [sic], conformity, and similarity of the ways Americans live . . .”[ix]

The conventional view of The Americans as a jeremiad is deemed the only valid interpretation, but such a reading often lacks empirical, internal evidence, and it fails to address a methodological problem, namely, does the apparent indictment of Americans in The Americans emerge from the subjects of the photographs in situ, with Frank merely recording the inevitable interpretation? Or did Frank have a premeditated theme to select images that illustrate a censorious objective? We are never told. Susan Sontag, for example, is unable to distinguish Robert Frank from Walker Evans, both of whom produce photographs that in her mind “reflect the traditional relish of documentary photography for the poor and dispossessed, the nation’s forgotten citizens.”[x] Since Sontag offers no examples, may we ask which pictures in The Americans exhibit “the poor and dispossessed”? It can’t be the wealthy couple in “Charity ball – New York City.” The blue bloods in “Cocktail party – New York City.” The owners of a brand-new Buick Riviera and Packard Clipper Deluxe in “Public park – Ann Arbor, Michigan.” What rigorous method of inquiry elicits a “sense of alienation, emptiness, and ennui” from which photographs in The Americans? What are the empirical sources that evidence “a deep-rooted sense of psychological isolation” in any one of Frank’s pictures? Apparently, evidence is not required when you can avail a Gnostic system of interpretation known only to art critics who have a grudge against America in the 1950s.

The conclusions predestine the observations, and Frank’s unique artistic vision is conscripted into serving snooty and stale opinions about American culture as perceived by academics and intellectuals. Indeed, the group thinking exhibits a troubling psychology that projects its demons onto every Frank picture. Why not just draw a moustache on Frank’s photographs and be done with it? On the occasion of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art’s recent retrospective, an article in Art in America informs us that The Americans is drawn from “. . . the country of J. Edgar Hoover’s sanctimony and the young Nixon’s shameless self-pity . . . ”[xi] despite the fact that none of the photographs in The Americans makes reference to J. Edgar Hoover or Richard Nixon or their presumed maladies. What is the critical mechanism that justifies such assertions other than the animating predisposition that America, and especially the America of the 1950s, must be reviled? What in the world motivates someone to write: “. . . nothing in the book [The Americans] directly indicates the witch hunt or lynch mobs or Senator McCarthy or Rosenbergs’ execution. . .”?[xii] Is it too obvious to ask if the litany of your villains is not directly indicated why do you bring it up? May we further ask: how are your villains indirectly indicated?

The all-too-common view of The Americans deprives Frank of his artistic vision and an aesthetic response (not to mention his mirth). Frank himself, lamenting reviewers who assumed that The Americans was meant as a rebuke of its subject matter, wrote “Reviews are bad. [They claim that] this book is sinister, perverse, anti-American. I am hurt, rather disappointed, but glad my work was used. The best I could hope for was that my book should be published.” [xiii]

Why can’t we take Swiss-born Robert Frank at his word? Mightn’t The Americans be Frank’s photographing what he saw, perhaps from a European (or for a European) viewpoint, as he traveled throughout America, making observations premeditated only by the artist’s eye? The results (long before the coercive rules of multiculturalism demanded it) record white people and black people, Christians and Jews, and yes, cowboys and Indians without submitting to sentimentality or pictorial conventions. The book’s title is “Americans,” not “America,” and there are no scenic photographs of sublime vistas; every photograph is of human beings or things human-made that may be characteristic of Americans.

Finally, one cannot fail to see that The Americans ends affirming life and love and cars. The concupiscence coda of The Americans: “Detroit” depicts an elderly couple riding in their car; “Public park – Ann Arbor, Michigan” captures young couples romancing in their cars; newly weds embrace in “City Hall – Reno Nevada.” “Indianapolis” portrays a young man and woman seated pillion as they ride a Harley-Davidson motorcycle and finally, the last photograph in The Americans, “U.S. 90, en route to Del Rio Texas,” features a woman and two small children in the front seat of car. But where is her husband? He’s taking the photograph; he’s Robert Frank lovingly dedicating his book to the companions on his journey looking at America.

As Francine Prose asked (with justification) upon visiting yet one more heavy-handed art show (in this case an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art):

Whatever happened to the quaint, old-fashioned notion that art should speak for itself, without explication, explanation, or apology? Whatever happened to the “visual” in visual arts, to the seeming self-evident idea that an image should be interesting, startling, original, engaging – or even beautiful – to look at?[xiv]

The ideological criticism that dominates academic criticism reduces art to the themes of class, race, and gender in a monotonous parade of essays and books substituting political purity for aesthetic response. In the absence of a shared iconography (replaced by a shared ideology), assigning significance to images becomes subjective, narrowing the possibility of complexity and aesthetic response, diminishing the artist’s imagination. While it’s tempting to say that the photographs in The Americans are misread, better perhaps is to lament that they are read at all, transforming the photographs into a narrative to accommodate the prejudices of the intelligentsia.

But Robert Frank is boxed in, the lid nailed shut: all those American flags, and even a Fourth of July picnic? C’mon, he has to be ironic. He has to be in the tradition of the documentary polemicists, producing tendentious images with all but cartoon balloon commentary. Frank is valued only if he is the American Hogarth.

Commentators of Robert Frank’s The Americans who assert that an essential characteristic of America in the 1950s was “mind-numbing conformity” demonstrate that that is something in which they all have broad experience.

[i] Anne H. Hoy, The Book of Photography (Washington, DC: National Geographic 2005), p. 297.

[ii] W.J.T Mitchell, What do Pictures Want? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), p. 275.

[iii] Philip Brookman in Robert Frank: Moving Out, ed. Sarah Greenough and Philip Brookman (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art), 1994, p. 148.

[iv] Graham Clark, The Photograph (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), p. 155.

[v] Vicki Goldberg and Robert Silberman, American Photography: a Century of Images (San Francisco: Chronicle Books 1999), p. 147.

[vi] Gerry Badger, “From Humanism to Formalism: Thoughts on Post-War American Photography,” American Images: Photography 1945-1980, ed., Peter Turner (New York: Penguin, 1985), p.15.

[vii] Newly minted cars are found in “Funeral – St. Helena, South Carolina,” “St. Petersburg, Florida,” “Drive-in movie – Detroit,” “St. Francis, gas station, and City Hall – Los Angeles,” “Chicago,” “San Francisco,” “Public park – Ann Arbor, Michigan.”

[viii] No dingy diners in “Ranch market – Hollywood,” “Luncheonette – Butte, Montana,” “Restaurant – US 1 leaving Columbus, South Carolina,” “Cafeteria – San Francisco,” “Drug store – Detroit,” “Coffee shop, railway station – Indianapolis.”

[ix] Sarah Greenough, Robert Frank: Moving Out, p. 114.

[x] Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus, Grioux, 1977), p.56.

[xi] Leo Rubinfien, “Another Trip Through ‘The Americans,’” Art in America (May, 2009), p. 138.

[xii] Ibid, p. 145.

[xiii] Robert Frank by Robert Frank (New York: Pantheon Books, 1985) no pagination.

[xiv] Francine Prose, “The Message Trumps the Medium at Whitney Biennial,” The Wall Street Journal, March 30, 2000, A28.

Terry Dunford, who received his doctorate in English from Marquette University (USA), is a retired college dean and humanities instructor. He has published in English Literary Renaissance, Art & Academe, Academic Questions, and other journals.

To comment on this article, please click here.

To help New English Review continue to publish interesting and thought provoking articles such as this one, please click here.

- Like

- Digg

- Del

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- Yummly

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Skype

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link