by Pedro Blas González (July 2020)

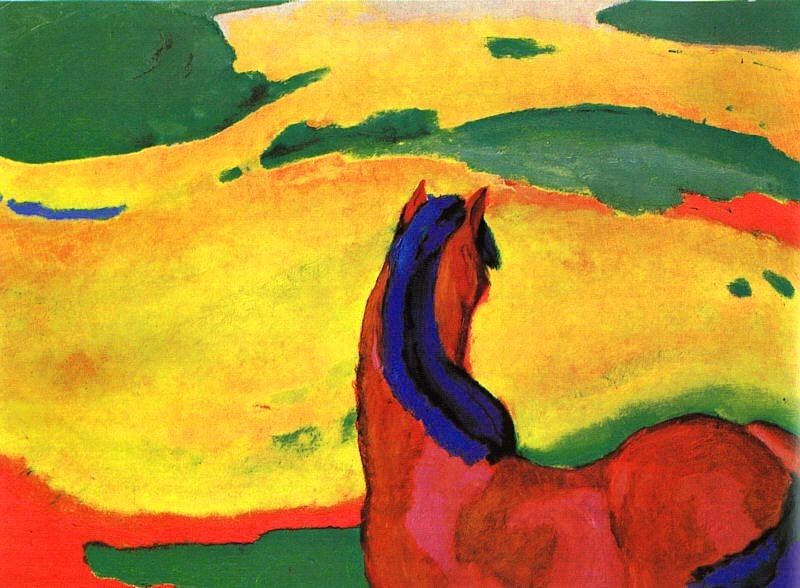

Horse in a Landscape, Franz Marc, 1910

The exploration of the American West by early pioneers is a story of possibility and promise. Tales of early American’s expansion into the West are a marvelous antidote to postmodernism’s cynicism, and intellectual and cultural stagnation.

Louis Dearborn L’Amour (1908-1988) explored universal themes in his prolific writing. While his novels are generally about the American West, they represent themes that speak to the human condition, even though inspired by the psyche of pioneering Americans. This is ignored by L’Amour’s academic critics, who allege that he and other western writers—for instance, Elmer Kelton—were merely proponents of American exceptionalism.

These critics, many whom are merely hollow chatter-boxes, miss the point of adventure stories. We do not encounter the breath of inspiration and self-rule of characters in L’Amour’s Hondo and Kelton’s The Time it Never Rained in postmodern writing.

There are three facets of L’Amour’s thought and writing that disarm intellectual dishonest critics: 1) He travelled extensively and has a lot of positive things to say about other cultures. In fact, L’Amour praises primitive cultures for being less primitive than some people believe. 2) L’Amour was an autodidact who had a burning desire for knowledge. This aspect of his work angers postmodern academic critics, elites who are self-appointed guardians of knowledge and culture. Other notable autodicacts include Mark Twain, Jack London, Eric Hoffer and Ray Brabury. 3) L’Amour was a consummate student; he researched the topic of his stories thoroughly.

Criticism of L’Amour’s writing comes from two quarters. The traditional critics of his work claim that western novels are not literature. Another criticism leveled at L’Amour is that he published paperbacks. He did so early in his career, for that’s how westerns were published in the genre’s infancy. These same critics also find fault with L’Amour’s characters: rugged individuals, who are often also righteous people. The charge levelled against these characters is that they are one-dimensional—too flat, the critics allege.

Yet these are the same critics who hail comic book and graphic novel characters as progressive. These critics applaud one-dimensional drug inspired counterculture characters in novels and cinema, whether from the West coast or the morally vacuous brainchild of Northeast literati.

The other type of criticism of L’Amour comes from postmodern deconstructionists. Lost in the virulent criticism of his work from intellectual elites is the understanding that his writing taps into what French philosopher, Gabriel Marcel, contends are objective values. Marcel, a Christian existentialist, argues that values are discovered, not invented. L’Amour’s writing explores the scale of human values.

The brilliance of L’Amour’s vision of man as a cosmic being is that values are not infinite in scope. In other words, values cannot be expanded ad infinitum by succeeding generations and expect them not to collapse in a great vat of contradictions. L’Amour’s work displays how moral collapse is the result of the balkanization of values, whether in the early American West, or circa 2020 postmodernism.

When we read L’Amour’s postmodern critics carefully—in the same manner that they “deconstruct” the thought of people who they suspect are their social/political adversaries—one uncovers glaring bad will and intellectual dishonesty.

The litmus test to expose intellectual dishonesty is to apply the techniques of deconstructionism to deconstructionists. If, as deconstructionism asserts, words only refer to other words, how can we take the claims made by deconstructionism seriously? Also, if texts subvert their own meaning, then deconstructionism deconstructs itself with every assertion.

Deconstructionism conveniently begins history at any random point. A spirited devil’s advocate can ask: Why not start with American Western expansion and disregard what came before? Deconstructionism is merely a destructive academic fad that promotes nihilism. Deconstructionism has discredited itself as being nothing more than neo-Marxist, pseudo philosophical fashion. Yet it has had a devastating negative effect on Western culture.

Bad will, which is the hallmark of postmodern critics—people who thrive on suspicion of the “other” as a potential enemy—is the corrosive cancer of radical ideology. Lamentably, this has found its way into philosophical and literary criticism. A thoughtful glance at these critics reveals the ugly face and raison d’être of people whose allegiance is not to literature, but radical ideology.

L’Amour, Avid Reader

L’Amour was a voracious reader. This is indicative of people who actually enjoy reading. L’Amour, a man who never completed high school, was fascinated with the acquisition of knowledge. He was interested in books that instruct people how to live and about man’s role in the cosmos. His reading was broad in scope. He discovered that great works also entertain. L’Amour used reading as a form of exploration. He embraced a manner of study that, like the great books, makes for a first-rate education.

Because L’Amour published 109 books, the wealth of his knowledge about the West and other subjects is dispersed throughout his collected work. But that is not why he wrote. He stated in interviews that story-telling was his forte.

Lifelong readers of the great books understand that human knowledge is a form of story-telling. Adventure, whether in Plato, Dante, Cervantes or Jules Verne, can be of the mind or physical exploration.

About L’Amour’s critics, one must ask: How many of them have cared to read a sampling of his work? This should concern critics whose aim is to dismiss his writing. Congenial critics who read a given number of a writer’s work discover recurring themes.

What is the purpose of literature? Why do we read? Regrettably, there exists a cottage industry that disparages the work of writers and thinkers out of envy, professional resentment, personal bitterness, and in postmodernity, radical ideology. These are motivations that dishonest critics will not admit. The German philosopher, Max Scheler, is correct that resentment is a profound emotion. Resentment, envy and other destructive human values exist in every culture. L’Amour taps into these dark values.

L’Amour’s short stories are equally replete with tales of good, evil and the rewards or retribution of human action. Often, his stories display the effects of self-destruction.

“Riches Beyond Dream,” traces the struggles of a man who has inherited land from his grandfather. Inheritance of land today, an age of legal deeds and a bevy of lawyers seems second nature. But how was this achieved in a previous age?

In “The Lonesome Gods” a lost man in the desert finds his way through the apparition of a mysterious Indian. In the “The Skull and Arrow,” L’Amour treats objective values as a template that people return to in order to make sense of reality, especially during difficult situations.

L’Amour’s novels are laboratories for the human condition condensed in several hundred pages. This appeals to readers. His novels serve as a web that exposes man’s dishonest interaction with each other. The latter is seemingly limitless in its variations. A brief sampling of his novels can offer us a glimpse into some of the themes L’Amour explores.

The Broken Gun

A writer, Dan Sheridan, investigates the mysterious disappearance of a family of ranchers and their large herd. The herd was stolen from them, including the deed of their ranch by the family of a thug named Colin Wells. How does a cultivated man respond to injustice?

The Haunted Mesa

The Haunted Mesa is perhaps L’Amour’s most enigmatic novel.

The work is a combination of southwestern motifs, horror and science fiction. In The Haunted Mesa the author uses his knowledge of the Zuni people and their Anasazi ancestor’s world of kachinas, kiva’s and the mysticism that these represent in developing a truly spectacular dream-world.

The Haunted Mesa is a work that deserves an essay of its own, for it is an original and refreshing science fiction novel. An investigator of paranormal phenomena discovers a portal to the other world, where the ancient ones (the Anasazi), operate a devilish, Big Brother state. Some of the dominant themes of the novel include reality and the possibility of other dimensions, including the afterlife.

L’Amour has a canny ability to describe landscape and create lively pacing. While some critics allege that L’Amour’s stories lack character development, he makes up with crisp storytelling, often making the landscape the protagonist.

The Tall Stranger

Rock Bannon is a loner, a tall stranger who helps a group of travelers going West. Their caravan is met by a cunning killer named Mort Harper. Harper wants to take away the vast land of Bannon’s stepfather, Hardy Bishop. Bannon is good will personified.

To the Far Blue Mountains

This is the second of the Sackett family saga novels. Barnabas Sackett, the patriarch, is wanted in England because of some coins that he found. He is accused of stealing them from the Queen. Barnabas tries fleeing to America. He is caught and taken to Newgate prison. He escapes with the help of friends.

To the Far Blue Mountains is a novel about the frontier; the discovery of America—especially the early settlements in the east coast—which L’Amour refers to as the frontier. America is the frontier.

Who is responsible for creating a nation? L’Amour suggests that in early American settlements, people had the opportunity to define their world socially, culturally and politically. This was a unique historical moment.

Describing the qualities of visionaries, one character says, “Also, he must have a rich, strong voice, but not one too cultivated. We tend to dislike and be suspicious of too cultivated a voice. A prophet’s voice should have a little roughness in the tones.” This reminds us of Plato’s contention in Laws that legislators must be virtuous.

The Warrior’s Path

The Warrior’s Path is the third of the Sackett family saga. The novel meanders from the mountains of North Carolina to the Caribbean, Jamaica, and back to America. Two young girls are kidnapped and forced into the slave trade. They are taken to Port Royal, Jamaica, a town teeming with cutthroats and pirates. Rin King Sackett goes with his brother Yance to rescue them.

It is often the case in L’Amour’s novels that his dominant themes take center stage, not plot. The Warrior’s Path is rather convoluted. Bravery, righteousness, law, order and civility carry this work.

High Lonesome

The novel takes its name from a mountain peak. An outlaw, Considine, and his gang rob a bank in the town of Obaro. They escape to Mexico. Considine wants to buy a ranch and leave the life of crime behind.

On the way to Mexico they encounter a young woman and her father who are pursued by Apaches. Considine must decide between saving the girl and her father or continue on his way. If he stops to help, he will be caught and executed. This is the type of hypothetical that academic teachers of ethics indulge in.

A life of crime never pays. Considine seeks redemption and the opportunity to practice virtue. He is not a hardboiled criminal, but has a weak character nonetheless.

The Ferguson Rifle

Ronan Chantry travels west after his wife and son die in a house fire. He meets up with fur trappers. He takes with him a Ferguson rifle—one of the first breechloading rifles—which was given to him by the inventor himself, Major Patrick Ferguson.

The Ferguson Rifle is an adventure story. A Spanish Captain named Fernandez wants to arrest Chantry for trespassing onto Spanish territory. Fernandez is accompanied by Ute Indians.

The Ferguson rifle motif is interesting because it enables a solitary man to have equal footing with gangs of men who do not fight alone and fair. The narrator suggests that hand to hand combat is more honest than fighting in groups.

Chantry is cultivated. He is considered a “scholar.” For this reason, he is thought of as being weak. The danger of over-intellectualizing reality informs L’Amour’s work.

Shalako

Shalako is a novel of action and adventure. While the work is about the American West, it follows the tradition of adventure stories of Melville, Stevenson and Conrad.

Shalako is a loner. Shalako’s introspection is reminiscent of Robinson Crusoe’s monologues. Crusoe’s reflective monologues are forced upon him by seclusion on a deserted island; Shalako’s reticence is forced upon him by the violence of other men.

Crusoe is a Londoner. His expects to return to England. Shalako is tainted by wild-country and uncivil men. Yet he is made more whole by the promise of love for a woman.

Hondo

Hondo explores several classical themes: Man’s injustice to man, romance and the lived-experiences of people who love each other; a fatherless boy who must come to terms with his own life.

In L’Amour’s work heuristic lessons do battle with the demands of daily life. L’Amour understood heroism as a form of being.

People who are unimpressed with the postmodern mania for naming—and how naming enables some people to maneuver superficially through reality—realize how intuitive L’Amour is as a writer.

As a form of being in the world, L’Amour’s conception of heroism follows in the tradition of Cervantes’ Don Quijote. L’Amour’s characters embrace quijotismo. Free will and individual essence are staples of people who cultivate contentment and the promise of a good life.

Last of the Breed

L’Amour wrote books and short stories other than western stories. In Last of the Breed, a Native American United States Air Force Pilot Major, Joseph Makatozi, is shot down by the Soviets and taken prisoner.

This is one of several L’Amour historical novels about the contemporary world. Self-perseverance, moderation and self-rule are dominant themes, only now the setting is a world that his readers better recognized.

L’Amour exposes a world of concentration camps, firing squads and depravity brought about by Soviet communism that still went mostly unreported by the free press in the late 1980s.

The Walking Drum

The Walking Drum is also a historical drama. This time the setting is 12th century Europe and the Middle East. The protagonist is Kerbouchard, a man who seeks knowledge and understanding, friendship, and love.

Kerbouchard is a natural aristocrat. Like Nietzsche’s Zarathustra or the ancient Greek philosopher, Diogenes, L’Amour’s protagonist cultivates stoic solitude, but is open to being surprised by a helping hand.

Kerbouchard is sure of himself: “Evil comes often to a man with money; tyranny comes surely to him without it. I say this, who am Mathurin Kerbouchard, a homeless wanderer upon earth’s far roads. I speak as one who has known hunger and feast, poverty and riches, the glory of the sword and the humility of the defenseless.”

The Hills of Homicide

L’Amour’s detective short stories are second to no other author in that genre. In The Hills of Homicide he takes his talent as a writer to the city, the urban landscape that is teeming with dereliction and cheap, disposable values.

In the introduction to this volume of detective and crime fiction, the author informs readers that “to become successful as a writer one must become story-minded, that is, he becomes able to perceive the story value of what he sees, hears, or learns.” This explains why deconstructionists and postmodern ideologues defile honest storytelling.

Louis L’Amour’s Frontier

This is a beautiful non-fiction coffee table book. L’Amour writes about the iconic places that inspired his fiction. The author uses the word frontier not only to mean the vast expanse of land that American settlers explored, but also as a description of America: “For some people the term ‘frontier’ may bring to mind only the way west. That is acceptable as long as one remembers that everything from where the Atlantic Ocean breaks upon the shore was west at one time.”

The beautiful pictures in the book are of rugged land, and, from a human perspective, lonely. If pictures tell a thousand stories, pictures of isolated, hard to get to places remind us of the natural aristocracy that exploration demands.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

________________________

Pedro Blas González is Professor of Philosophy at Barry University, Miami Shores, Florida. He earned his doctoral degree in Philosophy at DePaul University in 1995. Dr. González has published extensively on leading Spanish philosophers, such as Ortega y Gasset and Unamuno. His books have included Unamuno: A Lyrical Essay, Ortega’s ‘Revolt of the Masses’ and the Triumph of the New Man, Fragments: Essays in Subjectivity, Individuality and Autonomy and Human Existence as Radical Reality: Ortega’s Philosophy of Subjectivity. He also published a translation and introduction of José Ortega y Gasset’s last work to appear in English, “Medio siglo de Filosofia” (1951) in Philosophy Today Vol. 42 Issue 2 (Summer 1998).

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast