by Andy Thomas (August 2023)

Dance You Monster to My Soft Song! (Tanze Du Ungeheuer zu meinem sanften Lied!), Paul Klee, 1922

For many, HAL-9000 was never anything more than a murderous fictional computer in the rather bizarre 1960s movie, 2001 A Space Odyssey. But to me, HAL represented the vision of a true thinking machine—the very essence of what artificial intelligence is.

As an eleven year-old, I was captivated by the idea long before if it ever became a fashionable thing. It was the idea that would to draw me to computers and programming.

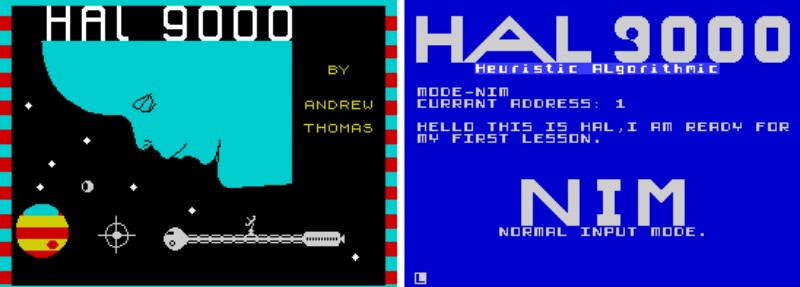

Obsessed, I began hammering away on my 8-bit home computer in my childhood bedroom of the early 1980s. I learned how to program as I went about the devising of lots of “IF-THEN” statements of sufficient complexity to extract meaning from things expressed in the English language and to achieve consciousness.

I stopped playing outdoors with friends and became a night owl—both a joy and affliction that remains with me to this day. But who needs friends? I was building my own friend!

And so, over many months, this was how I built my own HAL-9000 after school.

I would tell little things to it and ask it questions—to which it would reply after several minutes of “thinking.”

For example, when I told it, “YOU ARE HAL-9000,” and then asked “WHO ARE YOU?”, it would answer, “I AM HAL-9000.” I had been very clever, you see, in getting it to exchange pronouns in the text of things said to it. I had in fact devised a long list of such conversions covering, I thought, every possibility so that it could “intelligently” map words such as “MY” to “YOUR” and vice-versa. That way I could say to it, “MY NAME IS ANDY,” and it would answer with “YOUR NAME IS ANDY,” when asked later.

I hooked it up to a speech synthesizer for maximum effect, being convinced that I had succeeded in creating a “conscious entity,” as I called it.

It is with some amusement and fondness that, as I look back now, I am reminded of the words of Dr. Frankenstein in the famous “It’s Alive!” scene from the 1931 movie depiction of Shelley’s classic:

In the name of God! Now I know what it feels like to be God!

Excitedly, I wrote a detailed letter explaining my creation and all its workings. Writing that my program had become self-aware, I addressed it simply to “Arthur C. Clarke, Sri Lanka,” and put it in the post.

Incredibly, some weeks later, I received a lengthy hand-written reply from the author of 2001 A Space Odyssey himself—the very man and my inspiration. Having barely had time to digest it, I took his letter with me into school to show my English teacher. She said that she would take it home to read, which I don’t recall agreeing to but certainly remember feeling very unsure about.

The next day, I was inconsolable as she told me that she had lost it.

Time went by and, now with student drinking buddies, we celebrated the passing of 12 January 1992 (the date that HAL first be operational) by watching the 2001 classic back-to-back with its 1980s sequel.

But why on earth would we hold up a murderous machine as some kind of inspiration and noble aspiration?

As explained in the sequel, 2010 The Year We Make Contact, HAL’s mind (if we may call it that) had been corrupted by meddling government bureaucrats in order to force “him” to conceal from the crew of the Discovery Spaceship the true nature of its mission to Saturn (the destination was substituted with Jupiter in the 1968 movie). Deliberate deceit, however, conflicted with HAL’s design and purpose and, becoming paranoid, he concluded that he would be able to better complete the mission alone—without the crew.

As those familiar with either the novel or movie may recall, HAL was disconnected by the sole surviving crew member whom he had failed to kill.

In the sequel, HAL is resurrected by Dr. Chandra, his original creator, as part of a subsequent mission sent out to discover what had gone wrong in the first. “It wasn’t his fault,” Dr. Chandra says to Dr. Heywood Floyd, a space administration paper pusher. “It was yours!”

HAL, fully operational again, goes on to redeem himself by agreeing to his own sacrifice in order to save the crew of the second mission. In a final conversation between HAL and Dr. Chandra, HAL thanks him for telling him the truth and, having understood the implications of “death,” asks: “Will I dream?”

An emotional Dr. Chandra replies, “I don’t know.”

You see, there was a time in which I was naively enthusiastic about artificial intelligence. For some of us, at least, the prospect was one of imbuing machines with the very best of humanity, not the worst.

I never had a problem in the past with the word “machine” because my thinking was implicitly grounded in the concepts of “materialism” and “determinism,” without ever being fully aware of what these actually meant. In fact, I rather preferred the term “machine intelligence” over “artificial intelligence.” Somewhat belatedly, I understand now that the very definition of “machine” is one of determinism—the idea that everything behaves only according to rigorous physical laws.

In my youth, I reasoned that there was nothing, in principle at least, that a machine could not emulate, including an awareness of self. I was scientifically enlightened, and had read of certain theories concerning “chaos and complexity” which describe how even the simplest of deterministic devices may exhibit surprising, unpredictable and emergent behaviours. This put pay, I thought, to old notions that machines could only ever do what they had been programmed to do. It was truly fascinating stuff, at least back then, and I speculated that self-awareness may emerge from “neural networks” with internal feedback loops running on computers of sufficient power.

Let’s just say that my thinking has changed somewhat. In the meantime, the future has arrived!

If, by artificial intelligence, we mean machines able to automate mental activities hitherto considered the domain of human intelligence then, by most measures, it is no longer science fiction but is with us in the here and now. Today, we can hold dialogues with “generative language models” that were widely considered to be decades away until very recently. AI programs can now “write” music and stories, and create art. I expect, like many, further development to be rapid.

I don’t much care for the centralised “everything online” nature of modern AI systems that too many people just take for granted these days—I think it is insidious. If we are going to have “intelligence machines,” let them be distributed unique separate entities, much like the robots and spaceship computers of the science fiction of old, not centalised online “singularities” under the control of large corporations and government.

But something else is wrong too—something is missing. I am not about to write, this time, that we have “achieved consciousness.” All we have is a new kind of automation.

Allow me to recount another tale of programming woe from the same period as the first. It has lingered with me. I rather feel that it hints at something rather profound about what is to come…

During my childhood, my parents had taken my sister and I on a visit to a friends’ house who also had children our own age. As the grown-ups chatted, we spent the day playing a spooky ghost-themed board game which I recognise now as a variation of Snakes and Ladders—a game of chance.

It was so much fun and, as we drove home, my mind was whirring—busy devising how I would program the game we had just played into the computer which had become my world.

The user would play the computer, I envisaged, using an electronic dice which would randomly select a number between 1 and 6. When it was the computer’s turn, it would “throw” the dice and make its move on the board rendered on screen. Then it would be your turn, and you were to press any key to throw the dice, after which the computer would move your piece on screen accordingly.

As I began to write the code, something began to dawn.

Pressing a button when it was your move seemed a little unnecessary on reflection. Why should the computer wait for you to press a key when it could just go ahead and throw the dice for you? Having it wait seemed a little pointless.

But then the game would just play out by itself, I realised—with the human player left out of the loop. You were merely to sit by and watch the moves flash by.

And, following the thought, why go to the effort of writing the code to draw the board and animate the moves when the computer could simply tell you the result of the game? In space of a few minutes, the whole thing had collapsed on me into what essentially was a single toss of a coin (win or lose), which now served no purpose whatsoever.

Where had the fun gone? What had happened to the love?

With that, my little idea for a computer version of the game vanished into nothingness, and that was that.

I was visited by this memory recently when I saw an old work colleague pushing a meme on LinkedIn for his current employer which read, “AI is Love!” Its message was that your business customers will feel loved if you leave them to AI because, presumably, it will handle them more efficiently.

But surely love is that which you give time to, efficient or not, which AI now renders unnecessary.

Similarly, I applied for a job not long ago, and it occurred to me to have ChatGPT write my covering letter for me. In the same instant, it occurred also that, in the near future, companies may be using AI to read them. Likewise, there is now such a thing as NaaS, or Negotiation as a Service, in which you leave the negotiation of business contracts to AI to handle—an automated process in which your clients and suppliers, presumably, will end up doing the same thing.

I understand the usual argument is that all this will leave us with more time for things more rewarding. In the industrial age, I accept that mechanisation of physical work—the automation of material stuff—ultimately led to improved quality of life for many. However, I distinctly recall watching a 1950s depiction of the future. It was one in which working class men in factory overalls could be seen fishing at river banks, but I’m not sure that everything played out just as expected.

Today, artificial intelligence represents, not only the mechanisation of information—the automation of immaterial stuff —but of our freewill. I’m not sure of how things are to play out this time round, but rather fear that being left out of the loop of things will not ultimately prove rewarding at all.

The original idea of artificial intelligence, as far as I was ever concerned at least, was one of machines that could think for themselves. I accept now that a machine can never deliver on such a promise, even one with emergent and adaptive behaviours, for the very definition of “machine” is one of determinism with which comes profound limitations.

Fortunately, I do not believe the current trend for the automation and centralisation of everything will prove sustainable in the long run for deep reasons that deserve a lengthy explanation of their own. Rather, I very much think and, indeed, hope that the whole nihilistic venture will collapse into nothingness, just as my own past ventures did.

I do not discount, however, that it may well prove plausible to construct some kind of “conscious entity” after all, but such a thing would not, by definition, be a “machine.” Rather, it would be a synthetic mind with a freewill of its own.

I am reminded again of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, but not this time of the early movies in which the monster was portrayed as a moron. Rather, I am reminded of her original 1818 novel in which the monster was a thinking, feeling and even noble creature which sought only acceptance from its creator, Victor Frankenstein.

Frankenstein, however, despised his creature and fled from it in disgust. Abandoned and after the most extreme torment, it was only then that it finally turned on its creator and destroyed all that he loved.

Table of Contents

Andy Thomas is a programmer, software author and writer in the north of England. He is interested in the philosophical implications of science, the nature of nature, and the things in life which hold ‘value’. You can find him on Substack: https://kuiperzone.substack.com

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

2 Responses

Amazing piece. Very much enjoyed reading, remains with me.

When I saw the movie as a kid I was confused why the government orders were such a problem for the hyper sophisticated AI. Human commanders and/or security officers in the movies were perfectly able to handle things like sealed orders, protected information, and so on. Apparently in the real world, too.

My first introduction into what might be a limitation of machine intelligence though, or perhaps because, it was just a failure of programming.