by Kevin Anthony Brown (June 2024)

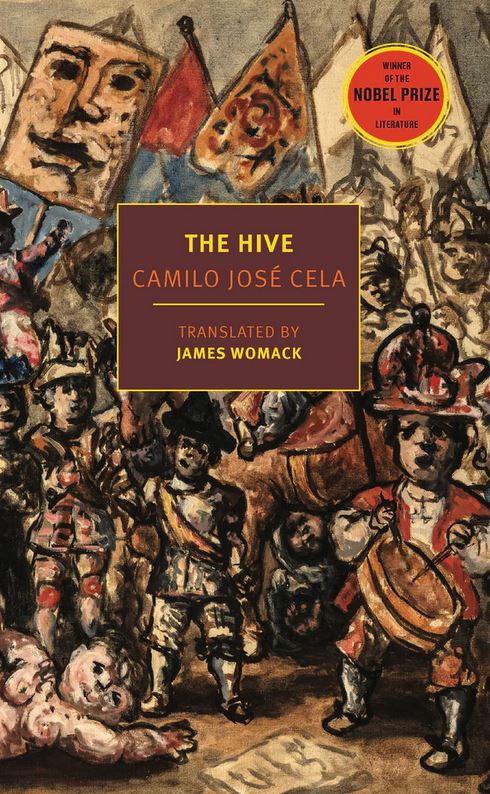

“People have said all manner of things about The Hive (1951),” gripes Camilo José Cela, “some of them good, some of them bad, and very few of them sensible.” Saul Bellow’s good review in 1953 was the exception to the rule. More typically, a different 20th-century reviewer conceded Cela’s “dark brilliance” while cautioning that libraries “beware.” James Womack’s translation is the first-ever uncensored and unabridged version in English. Now that the book has been reissued, Cela is in better hands. Because several of the novel’s 21st century reviewers—Tim Parks, Jack Rockwell, Adrian Nathan West—are themselves poets, novelists, translators and thinkers on language and the art of translation.

This novel resists Cliff Notes summarization. However arbitrary, careless, discontinuously episodic, fragmentary or willfully inconsequential it may seem on the surface, Cela’s lattice of recurring vignettes and storylines is perfectly adapted to his themes of loneliness and anomie.

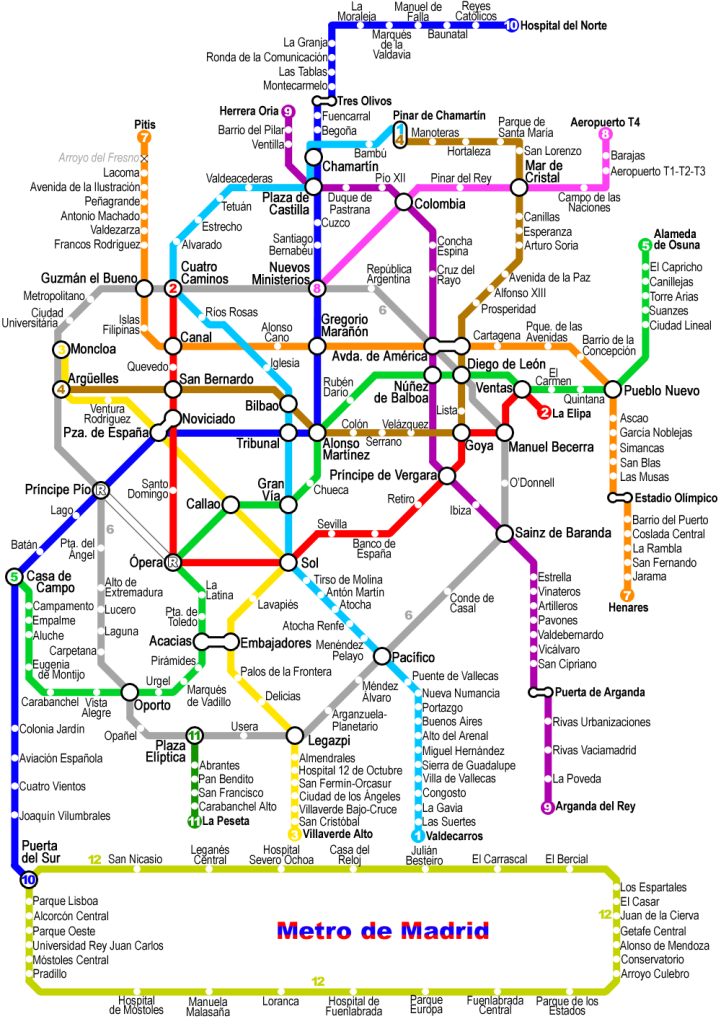

A honeycomb is a series of contiguous hexagons, with one cell bordered on all six sides by another cell. Compositionally, The Hive represents contiguous cell structures that seldom overlap. Six chapters subdivide into hundreds of brief sequences that honeycomb like tunnels through a subway. Think of The Hive as 215 exercises in style, variations on themes by turns anecdotal, compassionate, contemptuous, ecstatic, exasperated, hyperbolic, and/or understated in all their modulations. What may seem confusing are the rapid shifts between modalities; the modalities themselves are not confusing. The Hive is experimental but not haphazard or gratuitously difficult.

1. The Censor Uncensored

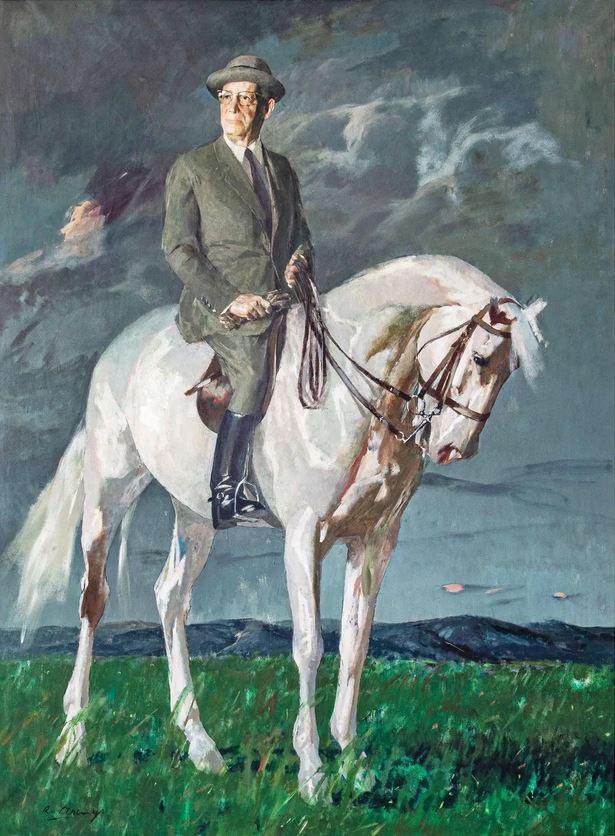

In The Hive, nothing is above ridicule—not political posturing, not literary pretension, not even his own work as government censor under Spanish generalissimo Francisco Franco. Cela’s duties? Scrutinizing newsletter content of kind caricatured in The Hive. An equal-opportunity provocateur like Cela would almost certainly be cancelled by sensitivity-readers today, as he was in his day, for his casual slurs against Chinamen, pansies, poofters, and punters.

In The Hive, nothing is above ridicule—not political posturing, not literary pretension, not even his own work as government censor under Spanish generalissimo Francisco Franco. Cela’s duties? Scrutinizing newsletter content of kind caricatured in The Hive. An equal-opportunity provocateur like Cela would almost certainly be cancelled by sensitivity-readers today, as he was in his day, for his casual slurs against Chinamen, pansies, poofters, and punters.

What was the perceived threat to Franco’s anti-communist, right-wing dictatorship? One can only speculate. Spain remained neutral during World War II, the years during which The Hive takes place. In the years preceding, when civil war broke out between Republicans and loyalist supporters of Don Carlos’ claim to the Spanish throne, Spain turned against and in upon itself. Posterity divides sharply on the question of how much blood was on Cela’s hands. Some criticize him for failing to distance himself from the Caudillo during Franco’s lifetime. Others allege that Cela falsely handed over to right-wing secret police the names of fellow-writers suspected of communist sympathies.

Cela does hint at how repressive life under dictatorship must have been. A telephone conversation is eavesdropped upon. An anonymous letter arrives certified mail: “A hundred eyes are watching you … we all know who you voted for back in ‘36.” Cela alludes to the “traditional Spanish parliamentary system” and ridicules “certain tendencies in contemporary political thought.” Yet, you can’t always infer Cela’s political position from what a given character thinks or says. Nobody in this novel seems bent on overthrowing the government: not the poet anti-hero who writes on scrap paper at the bank or post office because it’s warm and dry in there, who spouts empty leftist rhetoric about “the problem of society,” about the exploitation of the working class and price speculation, who idly ponders “the iniquities of economic distribution and the tax system,” scavenging the butts he rolls his cigarettes from (“what do I look like,” he asks, “a bum?”); certainly not the miserly café owner who sympathizes with Hitler. What these characters covet, if they already have money, is more money; or if they have no money a winter coat.

Cela’s social-realistic portrayal of migrants fleeing to Madrid from rural poverty belongs to a relatively backward and parochial World War II-era Spain, exhausted and famished. A child sleeps beneath a bridge in the cold or rain or August heat. Even those who aren’t yet homeless “tremble like schoolboys on the first of every month.” A musician lives on “two cups of coffee all day.” Landladies rent out rooms to those who rent their bodies out. This depiction could hardly have suited Franco’s mythic vision of what Rockwell calls “a unified, proto-fascist, Catholic Spain.” Maybe there’s a simpler reason The Hive was banned: chocolate éclairs. Fidel the Younger, a baker, catches a case of the clap. From that day on, he can’t stand the sight of long pastry tubes filled with a smooth, yellowy cream.

2. The Book of Names/The Book of Numbers

Cela’s censor-like dossier of proper nouns reminds this reader of the Old Testament Pentateuch. According to Wikipedia, the book of Numbers is so called because at the start God ordered a counting of the people (a census) in the twelve tribes of Israel. After counting all the men who are over twenty and fit to fight, the Israelites began to travel in well-ordered divisions.

Some names are more resonant than others; some numbers are meaningless.

Celestino, the tavern owner, recalls the name of a 15th-century novel written, similar to sections of The Hive, almost entirely in dialogue: La Celestina. The foul-mouthed parrot over there? That’s Rabelais. Cela might as well say, “novelists, poets, essayists, and philosophers there were, according to their kinds; from the Generation of 1898, Miguel de Unamuno, Pío Baroja, José Martínez Ruiz (aka Azorín) and others; from the Generation of 1927, Rafael Alberti, Vicente Aleixandre and Federico García Lorca; and, from the Generation of 1936, there was raconteur Camilo José Cela, who was wont to hold forth at El Gran Café de Gijón, or Café Comercial of the Glorieta de Bilbao.”

What Cela actually says, its absurdity being presumably the point, is: “Doña María Morales de Sierra—the sister of Doña Clarita Morales de Pérez, the wife of Don Camilo, the [podiatrist] who lived in the same building as Don Ignacio Galdácano, the man who couldn’t come to the meeting in Don Ibrahim’s house because he’s loco, is speaking to her husband, Don José Sierra, assistant in the ministry of public works.”

Cela seems to be hiding solid clues in plain sight amid red herrings. The sooner an impatient reader stops pulling his humorless hair out, realizes his leg’s being pulled, and gives up on the pointlessness of tracking these—166? 300?—names and apartment numbers on some asinine spreadsheet and relaxes into whatever kind of tale this joker’s confabulating, the more enjoyable his reading experience will be. A less idle speculation than the number of character-names in The Hive is how much does Benito Pérez Galdós owe to Balzac? And how much Balzac did Cela absorb directly from his own wide reading or from Galdós by osmosis? What Cela achieves is masterly and complex. It’s not that complicated.

Cela seems to be hiding solid clues in plain sight amid red herrings. The sooner an impatient reader stops pulling his humorless hair out, realizes his leg’s being pulled, and gives up on the pointlessness of tracking these—166? 300?—names and apartment numbers on some asinine spreadsheet and relaxes into whatever kind of tale this joker’s confabulating, the more enjoyable his reading experience will be. A less idle speculation than the number of character-names in The Hive is how much does Benito Pérez Galdós owe to Balzac? And how much Balzac did Cela absorb directly from his own wide reading or from Galdós by osmosis? What Cela achieves is masterly and complex. It’s not that complicated.

The Hive’s key integer is the number six, as in hexagon—a geometric shape both prevalent in nature and widely imitated in man-made environments for its ability to combine great strength with low surface area. A roiling honeycomb of hive-cells, like the crisscross of open-dot transfer-points, of vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines on a map of Madrid Metro stations,[1] personifies harried, siloed, jostled commuters.

Madrid was just a farming village when Rome ruled Spain. Publius Vergilius Maro, Roman poet, was a bee-keeper’s son. In Book IV of his Georgics, Virgil consecrates apiculture in about as many six-beat lines of Latin verse as there are characters in Cela’s hive. Virgil called his first collection of poems Eclogues. The Greek word means “selections” or “excerpts,” not necessarily bucolic idylls. There’s—almost—nothing syrupy about Cela’s Madrid eclogues. Counter-intuitive as it may sound, excess sugar is fatal to the honeybee. The Hive’s rare moments of sweetness stand out precisely because life for most of its characters—like that of an ailing bee, grounded, waiting around to die staggering over hot pavements in the pitiless sun with no hope of a Samaritan nursing her back to health with sugar-water—life is nasty, brutish and short.

Cela knowingly blurs names, faces, chronology. It’s coming on Christmas. It’s cold. We know it’s December. Beyond that, whether two or three days have elapsed is anybody’s guess. Because one queen bee attends mass seven days a week. Exchange rates and currency designators—reales, duros, pesetas, céntimos, cigarettes—matter less than what or whom or how much life money will buy or cost you: 20 roasted chestnuts; the obligation to walk a grumpy old hag around the Paseo; a visit to the doctor’s office; a hot meal; brief comfort in a sex worker’s cold arms; a teenaged-girl’s virginity.

Entomologists know the precise number of cells individual comb-frames have, know the number of bees in a hive. But sheer numbers matter less than does the division of labor. Sterile males drone on. Female workers flit to or exit from cell to cell within the hive. Some forage for pollen; others maraud their enemies or defend to the death against marauders; care for and feed their larvae; ceaseless groom their Queen; flee the hornet’s nest; or execute brutal cell-extractions, and unceremoniously dump their dead.

Bumblebee-flight is multi-directional; bees fly backwards, downwards, sideways or hover. Which makes swarms hard to swat. Botanists identify one part of the flower bees pollinate as its “style”. Cela’s style only seems to flit from pistil to flower. West notes that, in terms of content, Cela is a recognizably traditional novelist, despite The Hive’s novelty of form. Some of Cela’s sequences are very short, employing narrative devices every bit as conventional as those The Hive is wrongly accused of jettisoning: bad jokes & puns; cause & effect; description of interiors and exteriors (a park bench, an alleyway, a police station, an antique shop, a dive bar); a murder mystery; a suicide; shifts in point-of-view; motivational psychology; social observation. Endings cliffhanger; the pace quickens; the plot thickens. Line breaks and space breaks, even in scenes or dialogues that begin in media res, lend the text readability and breathing room. The rhythm and momentum never stall.

To casual observers all bees buzz alike. To warlike invaders or poet-entomologists like Virgil, the wiggle-waggle-dance of apiary signals intelligence is unmistakable. At the upper echelons of society, a marquis lies in state at the Escorial. At the lower depths and everywhere in between, a bartender says, “there’s all sorts of people out there” — beggars, bohemians, busboys, cops and con-artists, drunks, errand runners, night-watchmen, nuns, painters, porters, rumor-mongers (¡chismosos!), singers, snitches, street vendors.

Since they’re not fully rounded characters anyway, their names might as well be job titles like butcher, baker, candlestick maker. Had Cela put any more meat on these characters’ bones, The Hive would be what Cela, loosely translated, calls one long-ass novel.

3. Language Between Languages

Translation between languages is difficult because writing is difficult. Parts of speech are relatively few in number: adjectives, adverbs, conjunctions, nouns, prepositions, pronouns. Verbs have relatively few moods: imperative, indicative, passive or subjunctive. But the combinations are endless. In her essay “Translating from English into English,” Lydia Davis argues that writing is in itself an art of translation— “the activity in which a person brings something into being that did not exist before,” namely, “the raw data of the writer’s thought.”

Great writers are foreign-language writers, especially in their mother tongue.

Going back and forth between Cela’s Spanish and Womack’s English, sequence after sequence, chapter after chapter, is rewarding. Received wisdom has it that English, an unruly language with no time and less use for the subjunctive, is direct to the point of rudeness. Whereas Spanish, with its elaborate formalities, its dozen or more verb tenses and its peculiar redundancies of subject and direct/indirect object, is more circuitous, using eight words to express what could be said in five: a doña Montserrat le han robado el bolso. “They stole doña Montserrat’s purse.” She’s funny that way, la española.

But sometimes the opposite is true. Cela’s style is often startling for its speed and power. At the family dinner table, Victorita and her mother get into a shout-over match. Mamá le pegó dos tortas con toda su alma” — slapped shit out her, in other words.

Sense-for-sense fidelity to an author’s intent, to the extent knowable, is non-negotiable. Word-for-word infidelity to an author’s syntax or phrasing is often unavoidable. Not every linguistic problem has one right answer. Here, Cela’s original is unmatched for elegance and economy. Cada vida es una novela. “There’s a novel to be found in everyone’s life.”

Which is not to undermine the time and effort Womack invested in The Hive. On the contrary, it illustrates how very thoughtful his translation, that of a poet attuned to nuance, really is. In places, Womack’s pitch-perfect. The less vernacular, the more curricular Cela’s Spanish is, the closer Womack’s English tends to be. “What’s seven times four? Twenty-eight. And six times nine? Fifty-four. And nine squared? Eighty-one.” Here, it isn’t a question of being beautiful versus being true. It’s a matter of understanding that Cela’s not playing with language. He’s playing with interior monologue. An idler is caricatured by the numbing triviality of his preoccupations. Womack’s hard labor appears effortless when it comes to capturing the speaking voice of our Narrator, who tends to editorialize, “as you have already been told.” Whoever the Narrator is, he narrates in a cultivated, university-educated register whose lexicon corresponds to what West calls Cela’s “exacting, if sometimes showy, employment of the Spanish language.” In Womack’s translation and in the original, our Narrator’s syntax seems very close to that of so-called Standard English.

Where Tim Parks sees Womack struggling is when it comes to finding equivalents for Cela’s exuberant, dookie-stain-draws vulgarity. The problem a translator must solve for Cela’s juxtapositions of street slang and high Castilian, for the extent to which that slang—as Womack, having lived in Madrid from 2008 to 2017 is in a better position to know—may sound dated to 21st-century madrileño ears.

Cela’s frequency and subtlety of sly historical, literary and political reference, under dictatorship, are such that Womack would have needed footnotes or endnotes for almost every page. Scholarly apparatus New York Review Books Classics doesn’t provide can be found in the Royal Spanish Academy’s commemorative edition of La colmena, [2] which contains material censored from previous Spanish-language editions, as well as a glossary, bibliography, critical commentary and an index of character-names.

4. Languages Within a Language

More important than the number of names in The Hive is the variety of registers Cela deploys, what Rockwell calls “languages within a language.” Bravura is one word to describe the way Cela scales up, down and across Madrid’s linguistic registers—from prose poetry to melodramatic telenovelas to newsletter advertising copy. From the tertulia to the gutter, Cela documents jargon, doggerel poetry, journalism, legalistic syllogism, medical terminology and religious texts in a way technical translators would understand.

The Hive is, among other things, what Cela calls “an oral history of Spanish as she was spoken in the city of Madrid between about 1940 and 1942.”

As editor of the Diccionario Secreto (1969-1971), Cela compiled a glossary of profanities adopted by Spaniards as everyday usage. Even in one’s native language, much less a second language acquired fairly late in life, learning how to swear like a sailor is ranked an advanced proficiency.

The Hive’s literary and spoken languages extend to the irrational subconscious of Surrealism. Two dream sequences stick out: a black-cat nightmare composed as a solid block of text two pages long; and a loser’s delusions of martial grandeur. A fatuous windbag who shall remain nameless (he has six names), whom Flaubert would have butchered with sadistic glee, rehearses a speech full of empty postulations and expostulations, which “shine out with a blinding glory like that of the sun.” Chapter Six, which begins “Morning,” is an aubade, the tone-poem of a sleeping city coming to consciousness. The night before, Cela painted a nocturne of the city as living organism winding down to sleep, as bees do, when the last Metro clinks off to the yards: “you can hear [them]—old, rickety, falling apart, with the carriages working loose and their brakes harsh and violent—passing by, quite close, on their way back to the depot.”

English has its “linguistic” and “cultural heterogeneity,” to quote Rockwell. The American language, H.L. Mencken argues, is its own thing. Cela might agree with Zora Neale Hurston, a trained linguistic and cultural anthropologist, that Billy Bob Thornton’s genius monologue from Sling Blade is inextricably linked to Appalachia. The bewildering varieties of regional English as she’s spoken in West, East and Southern Africa, in the Caribbean, Europe, Southeast Asia and the South Pacific—these constitute languages within a language. It’s one thing that makes our vast literature rich.

A similar linguistic diversity exists within the Spanish-Speaking world. In Perú, you hear jijunagrandísima, roughly translated, hijo e puta. Queens, New York, is fairly typical of the many spoken varieties of Spanish. Seems only fitting Gregory Rabassa, who translated many works by the dozen Nobel Laureates representing the Iberian Peninsula and Latin America, should have taught so many years at Queens College.

Womack’s is a decisively British translation. You wouldn’t know it from the regionalisms he translates Cela into, but Womack was born and raised in the shire of and educated at the University of Cambridge. An American ear, one attuned to the varieties of English spoken in Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales (Llanfairpwllgwyngyll) may not readily distinguish where East Anglia ends and the East of England begins. Tactical risks Womack runs seem part of his larger strategy, as opposed to lapses in judgment, a strategy reviewers are bound to respect.

***

Cela’s extensive travels in Spain on foot became one subject of his many books. Some think The Hive his masterpiece. The 20 districts of its capital lie more or less at the geographic center of the nation. Greater Madrid tentacles out toward 49 other provincial place-names, from Asturias to Zaragoza. Fugitive houses, roads, avenues and sad cafés are a microcosm of the hive that is Madrid; Madrid is just one colony in an apiary of complex social structures called Spain; and the universe, which may or may not have a hive-mind of its own, is a macrocosm of which Spain is but an infinitesimal part.

Mario Vargas Llosa shares Cela’s admiration for José Ortega y Gasset. Vargas Llosa speaks of how, in The Dehumanization of Art (1925), Ortega “described, with a wealth of detail and great accuracy, the progressive divorce … between modern art and the general public.” Cela fought five years to reel this novel in working as fast as possible because he was as broke as his anti-hero Martín Marco, who somewhat resembles but isn’t necessarily Camilo José Cela, any more than narrator Marcel is necessarily Proust.

Marco reminds Bellow of Sartre’s Nausea (1938) or The Stranger (1942), by Camus. Is Cela’s flash-fiction “anthology of everything” greater than the sum of its parts? The question is tough but fair. One possible reply is that The Hive has aged so well because Cela was onto something. He understood that life as a fixed-duration construct of past, present, future is really just a dream. Loose ends don’t always get tied up neatly in literature, much less in life. Seen through a sometimes pixelated and other times high-definition lens, in Cela’s compound-eye view of what Hive reviewer Christopher Maurer calls the “uncertain and unforeseen ways in which human lives touch one another,” seemingly random events aren’t synonymous with meaninglessness.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Madrid-metro-map.png.

[2] https://www.buscalibre.us/libro-la-colmena-edicion-conmemorativa-de-la-rae-y-la-asale/9788420420684/p/47561849

Table of Contents

Kevin Anthony Brown is author of the essay collection Countée Cullen’s Harlem Renaissance: A Personal History (Parlor Press, 2024). At the City University of New York, he double-majored in Spanish as well as literary translation and technical interpreting (T&I), studying with Gregory Rabassa, translator of 100 Years of Solitude and many other works. Excerpts from Kevin Brown’s Spanish-into-English translation of Efraín Bartolomé’s Ocosingo War Diary: Voices from Chiapas (Calypso Editions, 2014) appeared at https://www.asymptotejournal.com. Essay-reviews by Kevin A. Brown on literature and translation have appeared in New English Review, Rain Taxi and The Threepenny Review, among others.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link

2 Responses

Hi, Kendra:

Great layout!

Kudos,

KB

Kevin,

Great content!

The package is complete.