Mandelstam by the Fence by György Faludy

by Thomas Ország-Land (October 2016)

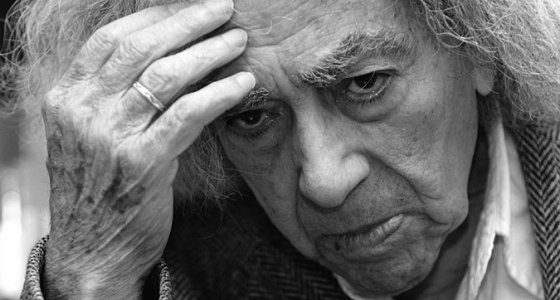

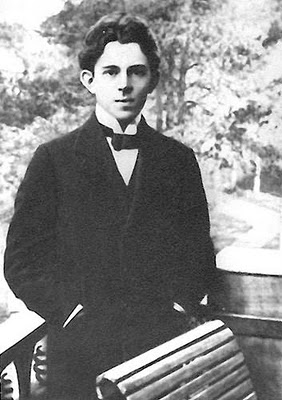

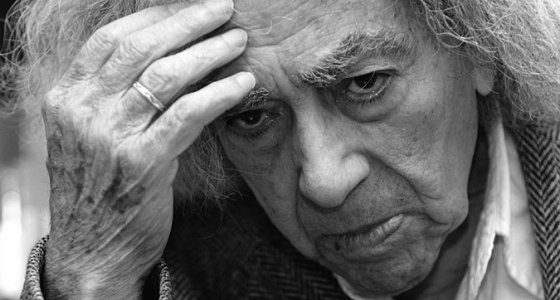

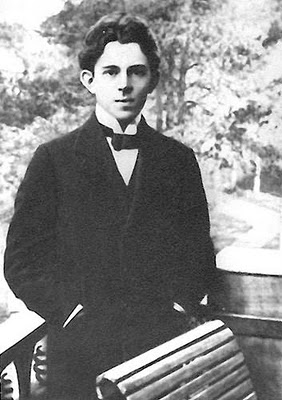

György Faludy (1910-2006), a Jewish-Hungarian humanist, was a towering figure of 20th century European literature and a dominant voice of the anti-Soviet and anti-Nazi resistance. His work in English translation is just beginning to take its rightful place in the bookshops, lecture halls and libraries of the West. He spent some of his most fruitful writing years in exile as well as political imprisonment where he had to entrust many of his poems – including the present piece, below – to memory. His work is once again heavily ignored by the servile Hungarian literary establishment under the country’s current, authoritarian rule. But the city of Toronto has adopted Faludy as its own poet and named after him a park beneath the apartment where he had spent 14 years of his exile. The poet Osip Mandelstam (1891-1938), another Jewish humanist, was murdered during Stalin’s purges in his native Russia, where his work is at last widely read.

FLEXING MUSCLES: A joint demonstration of power by Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany

Brest-Litovsk, 1939

Osip, you made me jump… Here I was squatting

near to the barbed-wire fence that runs along

the edge of this autumn woodland nearly bereft

of foliage, by the bed of a purple spring,

where I shed my role as a prisoner as soon as I

bent over the carpet of leaves beside my knees.

What wealth, what plentitude of colours and shades!

The melancholy brown of the horse-chestnut leaves

stretched out, their wrinkles straightened out, reshaped

by the smothering-iron of time, disintegrating

already in places but held together still

by networks of thread-like blood-vessels. Lying supine,

the leaves of oak trees still retained their spots

of green and red, reminders of bygone youth

and age, and here and there their surfaces blistering

like thickening porridge stirred on a cooking stove,

perhaps protesting the end of their sailing days

or mourning their flight with every passing breeze.

And then… two tiny leaves bent and conjoined

and shaped like flower petals or maybe a barge,

they must have fallen prematurely – but

from where? that leafless bush, I guessed, five paces

away, the one hardly taller than a dove.

I gently picked the pink one by two fingers

but did not sense a substance held between them.

Such leaves do not disintegrate, I mused,

they surely would evaporate tonight.

…And also hard and oval little leaves,

and others coloured like a bacon rind,

and tar-streaked, lemon-yellow leaves, like bygone

imperial flags, shed by a wild pear tree.

The other leaves did not expose the surface

to take the shape of tidy cigar wrappers,

I touched one, it rolled down along the slope

towards the shallow basin of the spring,

and many others fell in line behind it

until they stopped and huddled. Then I bent

down over their communal grave once more,

inhaled the heady, sylvan scent of death

shone through the branches. Even here, I sighed,

I am surrounded by such gifts of splendour,

and that was when I saw you standing there,

you, Osip Mandelstam.

Oszip Mandelstam

Beside the fence

you stood in your short jacket, with hat on.

The barbed wire fence was visible through your body.

Your face was very white and young and calm.

I knew that you would visit me. How often

I’d thought of you, at home, in bed, when I

lay drenched in sweat and tried to calm myself

by stroking my cool walls with my damp hands! and

how many times on my straw mattress here

when I am woken by the howl of bloodhounds!

Our destiny is one. We’ve much in common…

I do not like to bring this up, it may

sound bragging, still we two, and we too alone,

have dared to raise our voice in public poetry

to challenge Stalin in his own domain.

Why did you frown? I know we were not brave

(I take the liberty to speak for you

as we have shared one fate) we were not brave:

no, we were scared when we conceived our poems

and trembled while committing them to words

and we grew really desperate when the works

were finished and we found that they’d become

integral parts of us, our flesh, our bones…

Our images scared us from every mirror,

our constant fear drained out our very life-force

and, at our desks, we sat with shaking ankles

imagining them dangling in the air.

You raised your arm… what would you like to add?

I know. That this was very far from all.

That we were not just frightened, that we also

distributed our poetry, risking all,

perhaps because we sensed a hundred signs

that – verse or no verse – we would disappear

whatever we would do or fail to do,

not just for what we wrote, but who we were.

And we were not just scared, we were delighted

that some had at long last described our Genghis,

our linguist with the moustache of a cockroach,

the father of the nations gulping sickly

red Georgian wines upon a throne set high

on corpses… this our arid, biped death

whose orgasms explode not in his flesh

but in his cruel, calculating scull.

But why do I go on about the living

when you and I have so much more to say

as one corpse to another?... Or are you alive

in far Siberia in a camp, composing

verse after your dreadful daily load of labour?

How can you bear it? Or, have you surrendered?

Have you been beaten, worked or frozen to death?

Why don’t you answer?

Then the bell was sounded –

time for inspection, and I had to run

at once to try to make up for my absence.

Occasionally, I looked back. I thought

he might be gone. But no. He stood before

the fence in his short jacket and his hat,

barbed wire visible across his torso.

(Recsk slave labour camp, Hungary, 1951)

____________________________________________

THOMAS ORSZÁG-LAND is a poet and award-winning foreign correspondent who writes for New English Review on Europe and the Middle East. His last book was Survivors: Hungarian Jewish Poets of the Holocaust (Smokestack, 2014) and his last E-chapbook, Reading for Rush Hour: A Pamphlet in Praise of Passion (Snakeskin, 2016), both in England. His work appears also in current issues of Acumen, Standpoint and The Transnationalist.

To comment on this poem, please click here.

To help New English Review continue to publish translations of original poetry such as this, please click here.

If you enjoyed these poems and want to read more by Thomas Ország-Land, please click here.

FLEXING MUSCLES: A joint demonstration of power by Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany

Brest-Litovsk, 1939

towards the shallow basin of the spring,

and many others fell in line behind it

until they stopped and huddled. Then I bent

down over their communal grave once more,

inhaled the heady, sylvan scent of death

shone through the branches. Even here, I sighed,

I am surrounded by such gifts of splendour,

and that was when I saw you standing there,

you, Osip Mandelstam.

Oszip Mandelstam

Beside the fence

you stood in your short jacket, with hat on.

The barbed wire fence was visible through your body.

Your face was very white and young and calm.

I knew that you would visit me. How often

I’d thought of you, at home, in bed, when I

lay drenched in sweat and tried to calm myself

by stroking my cool walls with my damp hands! and

how many times on my straw mattress here

when I am woken by the howl of bloodhounds!

Our destiny is one. We’ve much in common…

I do not like to bring this up, it may

sound bragging, still we two, and we too alone,

have dared to raise our voice in public poetry

to challenge Stalin in his own domain.

Why did you frown? I know we were not brave

(I take the liberty to speak for you

as we have shared one fate) we were not brave:

no, we were scared when we conceived our poems

and trembled while committing them to words

and we grew really desperate when the works

were finished and we found that they’d become

integral parts of us, our flesh, our bones…

Our images scared us from every mirror,

our constant fear drained out our very life-force

and, at our desks, we sat with shaking ankles

imagining them dangling in the air.

You raised your arm… what would you like to add?

I know. That this was very far from all.

That we were not just frightened, that we also

distributed our poetry, risking all,

perhaps because we sensed a hundred signs

that – verse or no verse – we would disappear

whatever we would do or fail to do,

not just for what we wrote, but who we were.

And we were not just scared, we were delighted

that some had at long last described our Genghis,

our linguist with the moustache of a cockroach,

the father of the nations gulping sickly

red Georgian wines upon a throne set high

on corpses… this our arid, biped death

whose orgasms explode not in his flesh

but in his cruel, calculating scull.

But why do I go on about the living

when you and I have so much more to say

as one corpse to another?... Or are you alive

in far Siberia in a camp, composing

verse after your dreadful daily load of labour?

How can you bear it? Or, have you surrendered?

Have you been beaten, worked or frozen to death?

Why don’t you answer?

Then the bell was sounded –

time for inspection, and I had to run

at once to try to make up for my absence.

Occasionally, I looked back. I thought

he might be gone. But no. He stood before

the fence in his short jacket and his hat,

barbed wire visible across his torso.

(Recsk slave labour camp, Hungary, 1951)

____________________________________________

THOMAS ORSZÁG-LAND is a poet and award-winning foreign correspondent who writes for New English Review on Europe and the Middle East. His last book was Survivors: Hungarian Jewish Poets of the Holocaust (Smokestack, 2014) and his last E-chapbook, Reading for Rush Hour: A Pamphlet in Praise of Passion (Snakeskin, 2016), both in England. His work appears also in current issues of Acumen, Standpoint and The Transnationalist.