by Esmerelda Weatherwax (October 2010)

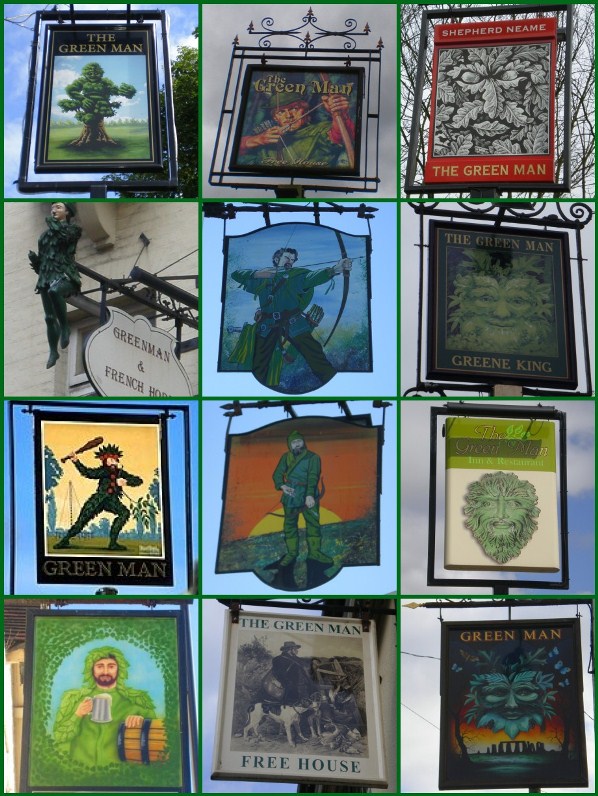

As you know I take an interest in pub signs of England, churches, and all sorts of other stuff. A popular name for a pub (less so since the advent of chain pubs all called Slug and Lettuce, or the Hogshead) is the Green Man. Further, the green man (as they are currently called) is an architectural feature ancient and modern.

I’m using as my main reference work here the Oxford Dictionary of English Folklore and the Pitkin Guide to the Green Man (which I bought in Norwich Cathedral, which has some of the most magnificent examples) which is followed by the small book Green Men of Gloucester Cathedral issued by the cathedral.

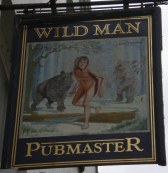

According to this there are two traditions currently going by the name Green Men. The first was originally often also called the Wild Men, or sometimes Wild Men of the Woods. In Elizabethan pageants they were often dressed in suits of leaves and carried cudgels. The Distillers Company had the Green Man and Still as their emblem and I think the sign (below 1) for the Green Man and French Horn pub in Covent Garden is a descendent of this. I don’t yet know why he had a French horn and how he lost it. The sign of the Wild Man pub in Norwich is left.

According to this there are two traditions currently going by the name Green Men. The first was originally often also called the Wild Men, or sometimes Wild Men of the Woods. In Elizabethan pageants they were often dressed in suits of leaves and carried cudgels. The Distillers Company had the Green Man and Still as their emblem and I think the sign (below 1) for the Green Man and French Horn pub in Covent Garden is a descendent of this. I don’t yet know why he had a French horn and how he lost it. The sign of the Wild Man pub in Norwich is left.

The other tradition is that of the foliate head, a carving which started to appear on churches around the 13th century, of a face either peeping through foliage or with foliage growing from it, often out of the mouth. These were given the name Green Men by Lady Raglan in an article she wrote in 1939 because she saw a resemblance between the carvings she saw in churches and the Green Man pub signs. The name has stuck, which in many ways is unfortunate as it has led to some churches underplaying their ancient carvings.

The Green Man/foliate head image is very popular at the moment. For some it symbolises ecological awareness and the ‘green’ movement. Others are more aware of ancient roots and trace the symbolism back into our Pagan ancestry. And not every church is happy about an association with what they perceive to be Pagan ancestry.

Last year on holiday I visited both Wells Cathedral in Somerset and Gloucester Cathedral. Gloucester is very proud of its Green Men, foliate heads, Flower faces and other strange carvings dating from the 15th century to the 21st. On the other hand when I inquired about the presence of green men at Wells the guide showed me the best example available to public view and said that at one time he was not allowed to present what a particular member of the clergy called ‘pagan symbols’ to the public but that the latest holder of that office thought differently.

Gloucester is so enthusiastic about foliate heads that over the centuries the Cathedral has commissioned new carvings. There are Victorian and 20th century carvings on the West Front. Very recently the Dean and Chapter and the City Council organised and funded the Storytellers bench in the grounds of St Mary le Crypt church which is the home of the National Centre for the Spoken word. This is a lovely project for children set near the local library, from which I hope generations get hours of enjoyment and inspiration.

The history of the foliate heads can indeed be traced back into to pagan history in that they are believed to have derived from the dignified leaf masks of late Roman art, which depicted Gods like Silenus. They became part of the repertoire of carving belonging to the style known on the continent as Romanesque which was introduced to England by the Normans. From the 12th century they became ever more varied and subtle, combining as they did two of the fascinations of the medieval artist, foliage and the human face. Some of the heads are animals, real or heraldic. This gentleman from Norwich to the left reminds me of Shrek.

The history of the foliate heads can indeed be traced back into to pagan history in that they are believed to have derived from the dignified leaf masks of late Roman art, which depicted Gods like Silenus. They became part of the repertoire of carving belonging to the style known on the continent as Romanesque which was introduced to England by the Normans. From the 12th century they became ever more varied and subtle, combining as they did two of the fascinations of the medieval artist, foliage and the human face. Some of the heads are animals, real or heraldic. This gentleman from Norwich to the left reminds me of Shrek.

I’m not going to attempt to list examples, and legends from the pre Christian and Christian traditions of North West Europe, such as that of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Robin Hood and the Jolly Green Giant, that may have influenced any individual carver who worked in both stone and wood, plain and painted.

There is a selection in the photographs below taken by either me, my husband or daughter over the last 2-3 years. So many places, all over England, over an 800 year period, trying to generalise too much could not do it justice. There are foliate heads in medieval glass as well, but I have not seen these personally. Later artists worked in ceramics and man-made materials. Victorian floor tiles of green kings at Rochester cathedral left.

There is a selection in the photographs below taken by either me, my husband or daughter over the last 2-3 years. So many places, all over England, over an 800 year period, trying to generalise too much could not do it justice. There are foliate heads in medieval glass as well, but I have not seen these personally. Later artists worked in ceramics and man-made materials. Victorian floor tiles of green kings at Rochester cathedral left.

Even the colour green is a misnomer. Where the carvings are coloured the leaves are frequently gold or brown (the best examples are in Norwich, in my opinion). They contain acorns or fruit rather than flowers, indicating that the figures are as much about harvest, autumn and fruitfulness, as they are about spring and new life, be that fertility or resurrection.

One theory is that early Romanesque ‘foliage spewers’ represented the sins of speech. Their position around doorways lead others to suggest that they may have been meant as Guardians of the Building. I know a 1930s art deco style Mecca Bingo hall with three above the main entrance. Many do suggest an inspiration from folk tales of wood spirits and creatures of the forest. They are often in out of the way places high on the roof boss or under a misericord.

Rochester is a good example of the contrast. The chap in the bottom left hand corner of the mosaic of photographs below is very high up. You wouldn’t want to meet him in the woods on a dark night. But barely 10 yards away on the ground is the tomb of Bishop Hamo who died in 1353. The foliate heads carved there (bottom row centre) are grave, dignified and thoughtful. Symbols of resurrection rather than ribald mischief.

It wasn’t until I walked into the cloisters of Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire that I realised a connection between foliate heads and the writings of St Hildegard of Bingen. As thoughts go it was original to me at the time – others had already made it in books that I have read since.

I don’t say there is a direct connection at Lacock although there could be. St Hildegard, a Benedictine Abbess died in 1179 and the Abbey was founded in 1229 as an Augustinian nunnery. I mean that both St Hildegard in her writings, the Abbess who commissioned the cloister carvings, and the artists who designed and made them were all working with an appreciation of the natural world as God’s great gift.

St Hildegard writing in Latin took great delight in the words vir, virgo, virga viriditas, man, maid, a flowering branch, the power to grow green. The first lines of her Song to the Virgin Mary have been translated as

Hail, O greenest branch, who came forth with the saints, like a gust of wind.

Lacock Abbey passed into private hands at the dissolution of the monasteries. A grand house was built where the Abbey church had been but few alterations were made elsewhere and the cloister is largely intact. So intact that it was used as a location for some of the Harry Potter films. The cauldron used when filming the Potions class was left as a reminder of a minor but fun episode of modern history. One of the first photographs ever taken was of the Oriel window at the Abbey by the pioneer William Fox Talbot in 1835.

The first thing you see when you walk into the cloister is the Green Lady, or foliate head of a beautiful young woman. Foliage comes from her mouth and intertwines with the plaits of her hair. If she is the Guardian of the Cloister she has done an excellent job since the 13th century. All the carvings of the roof bosses have a feminine air. There are dainty swans, several mermaids, a hind, four nun’s heads and a jolly dragon playing the harp. There are a few carvings of wild women about (eg Rochester again but I don’t have her photograph) but the lady at Lacock is the only definitely female foliate head I have heard of or seen.

To conclude, this is an enormous subject, of which I have barely scraped the surface and have not even attempted to decide where the Jacks in the Green of Mayday fit in. If, as I believe, the foliate heads and the green and wild men of the woods all come from our natural human appreciation of trees and growing things then they are connected in concept, despite their different recent histories.

I hope the photographs below give an idea of how wide and fascinating the subject is.

1 Green Man pubs – a history in miniature.

Left hand column from top to bottom

The Green Man Herongate Essex from 2009 – my absolute favourite showing the green man as a jolly tree spirit.

The Green Man and French Horn in Covent Garden.

The Green Man, Little Snoring nr Fakenham in Norfolk. I took this from the internet as it is no longer the sign of this pub. The leafy man and his pose is repeated at pubs elsewhere.

The Green Man, Plashet Grove, east London. I had to take this from the Pubsgalore website as the pub was demolished in 2008 and is now a block of flats. The leafy man enjoys a pint of best. RIP.

Centre row, top to bottom. The Green Man represented as that other figure of English legend, Robin Hood who dressed in Lincoln green and lived in Sherwood Forest. Work that out for yourselves. And a modern green man, a countryman in barbour coat, courduroy and green wellies.

The Green Man Edney Common

The Green Man Bradwell Waterside, facing left and right.

The Green Man Six Mile Bottom, Suffolk.

Right hand column from top to bottom. The modern preference for the foliate head.

The Green Man, Herongate 2010. The Shepherd Neame brewery have a policy of that their signs will be in house style ie black and white with red fittings. Their artists have produced some fine work within those limits, and this is an interesting example of the Arcimboldo technique but I miss my jolly green oak man. I hope he is safe somewhere and not gone to landfill.

The Green Man, Takely Street, Essex.

The Green Man Little Snoring, Norfolk 2009. The present sign.

The Green Man Toot Hill Essex. A sign which has taken the New Age interest in Folklore a little further. It’s a nice pub and next time we will indulge in the hog roast.

2 A selection of foliate heads. From top to bottom and left to right.

Two from the roof bosses in the cloisters at Norwich cathedral. The lady Chapel of Ely Cathedral.

A Flower face and ‘Mr Curly’ from Gloucester Cathedral. Wells Cathedral.

South Ockenden Parish church Essex, a roof boss removed to the ground in Southwark cathedral, above a door to the Boston Stump.

Rochester cathedral high roof boss, Bishop Hamo’s tomb Rochester, under an arch in Lambeth Palace, London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury.

3 The Green Lady of Lacock Abbey

4 Roof bosses of Lacock Abbey.

5 The Storytellers Bench Gloucester.

Detail of individual seats inset at bottom.

6 A 20th century example of foliate heads, unusual in that we know the names of the faces depicted. They are Mr Thompson and Mr McGinnity, the woodcarvers who worked in local oak to restore St Martins, Glandford, Norfolk. It’s a tiny church, a bit out of the way, but with the most finely detailed wood carvings.

Reference works consulted:-

Oxford Dictionary of English Folklore. Pitkin Guide to the Green Man. The Green Men of Gloucester Cathedral. A Little Book of the Green Man by Mike Harding.

For the quotations of St Hildegard of Bingen

The Wisdom of Hildegard of Bingen compiled by Fiona Bowie and Benedictine Tapestry by Dame Felicitas Corrigan.

Photographs E. Weatherwax and family unless stated from elsewhere.

To comment on this article, please click here.

If you enjoyed this somewhat eccentric piece and would like to read more by Esmerelda Weatherwax, please click here.

To help New English Review continue to publish interesting articles such as this one, please click here.

Esmerelda Weatherwax is a regular contributor to the Iconoclast, our community blog. To view her entries please click here.

- Like

- Digg

- Tumblr

- VKontakte

- Buffer

- Love This

- Odnoklassniki

- Meneame

- Blogger

- Amazon

- Yahoo Mail

- Gmail

- AOL

- Newsvine

- HackerNews

- Evernote

- MySpace

- Mail.ru

- Viadeo

- Line

- Comments

- SMS

- Viber

- Telegram

- Subscribe

- Facebook Messenger

- Kakao

- LiveJournal

- Yammer

- Edgar

- Fintel

- Mix

- Instapaper

- Copy Link