Mao Then, Mao Now

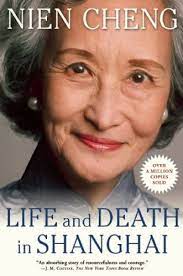

Thoughts on reading Nien Cheng’s Life and Death in Shanghai

by Albert Norton, Jr. (October 2022)

For those of us who’ve been around for more than a couple of decades, the events of the awful mid-twentieth-century wars still loom large in the imagination. We can see that the ideologies that drove the conflicts then are still very much in play now. But time rolls on, and with new generations, appreciation for the relevance of those events and ideas may fade. There is a historical record, however, and from time to time we should pull it out and review. Nien Cheng’s Life and Death in Shanghai (New York: Grove Press 1986) is an important part of that record.

In her book, Cheng recounts her experience of the Chinese cultural revolution commencing with Mao’s loosing of the rampaging Red Guards in 1966, when she was 49 years old. She was a political prisoner for six years in the “Number 1 Detention House” in Shanghai, and relates her experience there, but also her understanding of evolving political and cultural developments in China during that time.

In her book, Cheng recounts her experience of the Chinese cultural revolution commencing with Mao’s loosing of the rampaging Red Guards in 1966, when she was 49 years old. She was a political prisoner for six years in the “Number 1 Detention House” in Shanghai, and relates her experience there, but also her understanding of evolving political and cultural developments in China during that time.

The degree to which Chinese citizens tried to conform their speech and even their very thoughts to Maoism is alarming. And not just official Maoist dogma, but the various subtle revisions to it as different power factions came and went over the years. Another book suggests the unique vulnerability of Chinese society to this all-encompassing totalitarian communism: The Tyranny of History/The Roots of China’s Crisis, by W.J.F. Jenner (1992). They would have a block captain, for example, so imagine someone on your street is appointed leader of your street, and someone above them the leader of your neighborhood, and so on. Every time you go somewhere or interact with a foreigner or change jobs or anything of note otherwise, you have to check in with the police and keep them apprised. So the Chinese brand of communism has roots in its peculiar social structure dating back thousands of years.

A couple of anecdotes that bear witness to the long-standing effects of Maoism. Back in the early ‘oughts, my family hosted a group of Chinese visitors on a business trip. They found it noteworthy that in America we openly criticize (or at least did at that time), even about political matters. They described how, when they hear public pronouncements together (and that’s what they do, they’re compelled to hear them in groups) they never criticize, instead they make comments on how good the developing policy is; how advantageous for them, etc. There’s no thought of criticism, constructive or otherwise.

Then more recently we hosted a young Chinese man for a brief visit, and he was open to talking about religious belief. I asked him what he thought about the church service we’d just attended and that led him to say that in China “we don’t believe in God,” and though I asked in different ways, it struck me that this very intelligent young man was unable to consider a belief that deviated from that of the Chinese collective. “We,” not “I.” The very concept of forming an individual opinion was foreign to him. Acquiring truth on this subject (or any other) was a social matter.

We should ask to what degree we are becoming China. Cheng in 1966 was a rare individualist dissenter in that society. An American at that time would have a hard time imagining the collectivism of China under Mao. But how about today? Does it not seem that compared to 1966, Americans are much closer to the presumptive collectivism that obtained then in China, and that remains there, as its communism has evolved?

Cheng was persecuted for years because she wouldn’t “confess” even though she had nothing to confess to. What she was really guilty of was dissent from belief in socially-formed belief. She would not accept the factually false narrative concerning her life, and was therefore a thought criminal. At some point it was necessary to break her down because she wouldn’t acquiesce to what was yelled at her in innumerable struggle sessions. A struggle session is one in which your friends, neighbors, and co-workers assemble to scream accusations and completely made-up facts to break you down over your lack of worship of Our Great Leader Chairman Mao and every pithy saying he wrote in those idiotic red books written for barely literate soldiers and impressionable teenagers.

Here’s an illustration of how the thought control is premised on willingness to lie, and to deny objective truth. Cheng is in the Number 1 Detention House, being interrogated for the umpteenth time. Constantly being told to confess:

“I’m not a magician. I don’t know how to confess to something that did not happen.”

“Perhaps you are not ready yet. We are patient. We can wait.”

“A million years would make no difference. If something didn’t happen, it just didn’t happen. You can’t change facts, no matter how long you wait.”

“Time can change a person’s attitude. Your health will break down. Eventually you will be begging for a chance to confess. If you don’t you will surely die.”

“I’d rather die than tell a lie.”

***

“Am I not to expect justice from the People’s Government?”

“Justice! What is justice? It’s a mere word. It’s an abstract word with no universal meaning. To different classes of people justice means different things. The capitalist class considers it perfectly just to exploit the workers, while the workers consider it decidedly unjust to be so exploited. In any case, who are you to demand justice? When you sat in your well-heated house and there were other people shivering in the snow, did you think of justice?”

“You are confusing social justice with legal justice ..”

“[W]e are not concerned with the abstract concept of justice. The army, the police, and the court are instruments of repression used by one class against another. They have nothing to do with justice … The capitalist countries use such attractive words as ‘justice’ and ‘liberty’ to fool the common people to prevent their revolutionary awakening …”

Everything old is new again. This is Marxist dogma that was already tired and threadbare before these events in 1966-76. Capitalism (or in our day, “objectivity” or “whiteness” or logocentrism or fascism) stands in for imagined systems of oppression which seem to warrant oppression from the opposite direction. It’s a shift from idealism to naked power as the basis upon which we interact. It’s the reason civil war is not unthinkable now in the United States, and for the same reasons as in China in the early 30’s through 1949 when the Maoists prevailed and brought a locust horde of evil.

This idea that Cheng was expected to capitulate because of the sheer passage of time is of philosophical interest. We deviate from truth and may cave to pressure to live in lies because we fail to recognize the eternality of truth. If there is no God and no eternal portion of our being, then all is contingent and relative, and there really is no point in standing for supposedly universal and eternal values like justice and liberty.

The Maoists were right that people can manipulate or exploit while claiming they stand on principle. But that’s exactly what the Maoists themselves were doing; they just derived their principles from social process rather than transcendent truth. And that’s exactly what is happening around us right now, in the postmodern dispensation of the West.

In her delirium brought on by illness, cold, and starvation, Cheng suggested to her guards that her daughter could stay in the cell with her. It wasn’t entirely a selfish instinct to do so, because she worried her daughter would suffer a fate as bad or worse than hers. And in fact, (spoiler alert), unbeknownst to Cheng at this time, her daughter had been murdered already:

“I’m worried about my daughter. Could she be brought here to stay in this cell with me?”

“Of course not! She hasn’t committed any crime. Why should she be locked up in prison?”

“I haven’t committed any crime either, but I’m locked up in prison just the same.”

“I have no time to argue with you about that. Whether you committed any crime or not, I don’t know. In fact, I don’t know anymore what’s a crime and what’s not a crime … ”

The guard doesn’t know what’s a crime and what’s not because right and wrong is no longer pegged to the conscience, and to eternal and unchanging right and wrong, but instead to social process, exactly like what we’re seeing in our country now. The Maoists who “followed the Party line closely” were exquisitely attuned to little shifts in what is approved and what isn’t:

Because they seemed to maintain their positions through every twist and turn of the party’s policy, they became the example for the young generation of Chinese to emulate. The result was a fundamental change in the basic values of Chinese society.

Of course that is the result. The Chinese today continue to say they’re communists, but it’s obvious their society has moved on from the fundamentals of revolutionary Marxist/Leninist/Maoist doctrine. They’ve become fascist, because that is the correct word for centralized overpowering government that aligns with and reinforces other social power centers and does so by changing “basic values” from objectivity to relativism, governing through social norms.

How? Subtly. One of the newly-inculcated social norms is acceptance of social norms. This is why Maoism is relevant in the West today. As we’re fed new narratives to form social norms, we may overlook that one of the new norms is acceptance of new norms. In this way social norms take the place of objectivity. It’s a kind of large-scale Stockholm syndrome. You’re to be grateful for any break from grinding oppression, once oppression is normalized. But it’s not necessarily an oppression of privation and coercion, like in 1984; rather it’s an oppression of meaningless satiety, like in Brave New World. The individual self is enervated, hollowed out from the inside, so there’s no fight left, as there might be with insulting face-to-face Nazi-like force. You’re fed ideological dope to make you not care so there’s no more you to fight for.

Cheng had been in prison for years for no crime and not even provable dissension from the Maoist version of Marxism; kept in solitary confinement, dark and dirty conditions, starved, cold, and cut off from her family and the outside world aside from “news” that was plainly propaganda, when she experienced a moment of transcendence in stark contrast to the dark sea of sameness and persecution she was forced to navigate—a glimmer of hope originating in the “superstition” Marxism was supposed to sweep away. In solitary confinement, in the cold dark of night which she’d calculated to be Christmas Eve, she heard a soprano voice singing the Chinese version of Silent Night. Softly at first, but gaining confidence and piercing beauty, until she heard a rush of guards to where they supposed the sound to have come from. None of the prisoners, normally so eager to reinforce the social norm of ideological purity, would identify the songbird.

This book does not describe a long-ago historical anomaly, but is relevant right here, right now. And Cheng’s experience on Christmas Eve tells us how we begin to resist.

Albert Norton, Jr is a writer and attorney working in the American South. His most recent book is Dangerous God: A Defense of Transcendent Truth (2021) concerning formation of truth and values in a postmodern age; and Intuition of Significance, a 2020 work weighing the merits of theism against materialism. He is also the author of several award-winning short stories, and two novels: Another Like Me (2015) and Rough Water Baptism (2017), on themes of navigating reality in a post-Christian world.

NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast