by Boyd Cathey (July 2019)

.jpg)

Lurelei, Karl Begas, 1835

German composer Max Bruch may seem an unlikely champion of the Romantic classical music tradition. Known mostly for his First Violin Concerto, his Scottish Fantasy, and his setting of Kol Nidrei (Bruch wasn’t Jewish, but was attracted to this theme), he stood in the shadow of the better known and more famous Johannes Brahms as representative of what is sometimes called German “musical conservatism” in the second half of the nineteenth century—a faithful continuation of the traditions of Beethoven, Robert Schumann, and Felix Mendelssohn, as opposed to the newer trends heralded by Richard Wagner.

Yet Bruch was no mere epigone of Brahms or the older nineteenth century classicists. In his day he was highly regarded, and not just for the works we now associate with him. He composed in nearly every genre: symphonies, chamber music, choral and liturgical music, songs, and opera. During his long life (1838-1920) he witnessed musically, first, the efflorescence of German Romanticism with Mendelssohn and Schumann, the advent of the “New German” school of Franz Liszt and Wagner, and then later, composers of the early twentieth century—Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Alexander von Zemlinsky—who seemed to bridge a chasm towards a kind of avant-garde musical anarchy, a period that Sir Simon Rattle has termed “sitting on a volcano.”

Yet Bruch was no mere epigone of Brahms or the older nineteenth century classicists. In his day he was highly regarded, and not just for the works we now associate with him. He composed in nearly every genre: symphonies, chamber music, choral and liturgical music, songs, and opera. During his long life (1838-1920) he witnessed musically, first, the efflorescence of German Romanticism with Mendelssohn and Schumann, the advent of the “New German” school of Franz Liszt and Wagner, and then later, composers of the early twentieth century—Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Alexander von Zemlinsky—who seemed to bridge a chasm towards a kind of avant-garde musical anarchy, a period that Sir Simon Rattle has termed “sitting on a volcano.”

The last years of his life saw the premiere of impressionist Claude Debussy’s scandalous ballet version of “L’Apres-midi d’un faun” (Paris, 1912, with dancer Vaslav Nijinksy simulating sexual activity on stage) and Igor Stravinsky’s equally controversial, “Le Sacre du printemps” (1913), and, lastly, the atonality of Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern and Alban Berg, and the Second Vienna School.

Until his death Bruch rejected any form of modernism in music, what he called “musical social democracy.” As a boy he had experienced the Revolution of 1848, and the same negative impressions he gathered then he expressed continuously up to his death after the fall of the German monarchy under which he had had his greatest successes and long after most of his former contemporaries had passed from the scene.

Read more in New English Review:

• From the Magical Land of Ellegoc to the First Man on the Moon

• Gratitude and Grumbling

• Jarrell’s Little Lady and the Race Police

By 1920 his style and aesthetic had been overthrown by the boldness and newness of the modern era. According to music critic Andrew Desiderio,

Bruch’s timelessness was at odds with the timeliness of his contemporaries. I say all of this because in order to appreciate…Bruch’s music in general, we need to listen not with 21st-century ears, which have been conditioned to embrace novelty and reject anything with a whiff of similarity to somebody else, but with human ears that can appreciate the intellectual and emotional beauty that exists in music of substance, irrespective of the time as we know it. [Andrew Desiderio, Review of compact disc of Bruch, String Quintet in Eb. String Quintet in A. String Octet in Bb, in Fanfare magazine, September/October 2017, vol. 41:1, p. 183.]

Years ago, I remember first encountering Bruch’s three symphonies. Like most classical music listeners, I was familiar with his “biggest hits,” but the symphonies I found incredibly attractive, well-composed and fine melodic examples of “high” Romanticism. And I wondered then why they weren’t performed more often, as they certainly seemed to merit that. After all there were complete and easily obtainable traversals by James Conlon and Kurt Masur on disc. Why wouldn’t some impresario begin programming them?

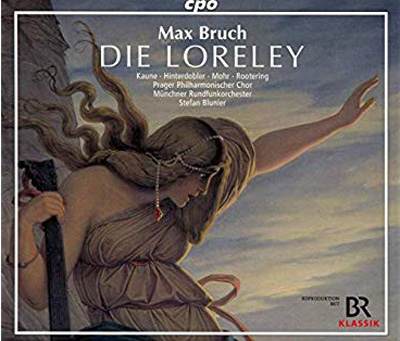

That same thought came to me as I listened to Bruch’s “grand romantic opera,” Die Loreley, released now on compact disc by the CPO label (cf. reviews in BBC Music Magazine, April 2019; Gramophone, March 2019; MusicWeb International, April 2019; and Opera, April 2019). Bruch wrote Die Loreley when he was only in his twenties (1863), and it was premiered in Mannheim with a starry audience that included conductor Herman Levi, composers Anton Rubinstein and Joseph Raff, and Clara Schumann. As Bruch’s biographer, Christopher Fifield, recounts, Schumann after attending the performance praised Bruch’s music and craftsmanship. Despite some weaknesses in the libretto, she found that

there are very beautiful moments in it, with the orchestra and chorus treated with such mastery throughout that I can hardly comprehend it from such a young composer . . . I will certainly not miss the chance to hear it again, for now I can only speak of my first impression, and please do not believe I would let this stand as my verdict . . . I found certain moments of Die Loreley wonderful. [Christopher Fifield, Max Bruch: His Life and Works, 1988, p. 45, quoted from a letter to musician Ferdinand Hiller.]

Emanuel Geibel, Bruch’s librettist, had originally written the text of Die Loreley for Mendelssohn, but Mendelssohn never finished the project. And Geibel’s libretto languished until taken up by Bruch who was captivated by its simplicity and folkish character. But Schumann’s view of the libretto was echoed in contemporary critical appraisals of the work. In addition to subsequent performances in Prague and Rotterdam, Die Loreley was taken up by only a half dozen opera theaters in Germany and soon disappeared from the repertory. A new version was staged in Leipzig in 1887, with Bruch’s approval, an apparent attempt to strengthen what was perceived to be the weakness of Geibel’s text. The Leipzig production was prepared under the young Gustav Mahler, and as performed was successful and then saw new life in Breslau, Cassel, and Cologne. Thirty years later, in the midst of World War I, composer Hans Pfitzner, director of the Strasburg Opera, revived it once again (March 26, 1916). Although the now-elderly Bruch disliked Pfitzner’s music, he warmed to the Strasburg project; and both men agreed to the staging of the earlier edition which they found preferable.

At first it may seem odd that Hans Pfitzner, whose musical language appears so foreign to that of Bruch, would champion the conservative Romantic. Yet, as Leon Botstein has written:

For Pfitzner, Bruch was a quintessential ideal German cultural figure. Furthermore, Bruch, far from being an academic and uninspired post-Mendelssohnian figure and rigidly anti-Wagnerian, was—correctly, in Pfitzner’s view—a great underrated composer with singular melodic and dramatic gifts who sought to participate in a German cultural renewal after the unification of Germany in 1870 . . . [D]espite the audible evocations of Wagner, Bruch sought to fashion an aesthetic alternative that redeemed traditional musical practices against Wagner’s dismissal of them . . . Just as Pfitzner used the sounds and contrapuntal techniques of the sixteenth century in a modern score, Bruch employed past models (particularly Bach and Handel) for his own ends. For both composers, the forms of the past were not, as Wagner suggested, dead, nor were the musical procedures on which these forms depended. [Leon Botstein, “Pfitzner and Musical Politics,” The Musical Quarterly 85(1), Spring 2001, pp. 63-75]

In November 2014 Die Loreley was revived in a non-staged concert performance in Munich (apparently the 1863 original version), and that revival is the source for the CPO recording.

CPO is a German label (Concert Produktion Osnabruck) founded in 1986, with the goal of recording and making available neglected repertory largely from the nineteenth and first part of the twentieth centuries. In so doing they have concentrated on composers from central Europe and Germanic lands, including August Klughardt, Felix Woyrsch, Heinrich von Herzogenberg, Felix Draeseke, Louis Spohr, Franz Lachner, and others. Regional, but uniformly excellent German-based ensembles have usually been featured, revealing relatively high standards of music-making in central Europe.

CPO is a German label (Concert Produktion Osnabruck) founded in 1986, with the goal of recording and making available neglected repertory largely from the nineteenth and first part of the twentieth centuries. In so doing they have concentrated on composers from central Europe and Germanic lands, including August Klughardt, Felix Woyrsch, Heinrich von Herzogenberg, Felix Draeseke, Louis Spohr, Franz Lachner, and others. Regional, but uniformly excellent German-based ensembles have usually been featured, revealing relatively high standards of music-making in central Europe.

Although the label is known widely for its issuance of the complete symphonic works of many of these unknown composers, it has also explored quite successfully the operatic repertory of the era, various once-popular but now largely forgotten works which have virtually disappeared from the boards. Thus, operas by Otto Nicolai besides his comedic masterpiece The Merry Wives of Windsor (e.g., Il Templario and Die Heimkehr des Verbannten), Franz Lachner (Catarina Cornaro), Emil von Reznicek (Donna Diana, with its famous “Sgt. Preston of the Yukon” theme), and others, have been recorded and released to critical acclaim, offering listeners a much broader musical understanding and appreciation of that period.

And CPO’s Die Loreley release, a co-production with Bavarian Radio, demonstrates that the opera merits more consideration in our age.

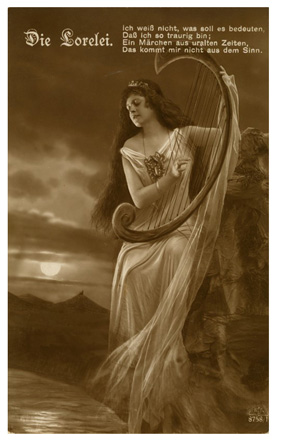

The legend of the Loreley is not ancient; it was in fact first created by German writer Clemens Brentano and published in his novel, Godwi (1800-1801), in which he narrates the tale of an enchantress of great beauty, spurned in love by men, who leads them to their death and then casts herself from a cliff into the Rhine River. As Florian Heurich writes in his album annotations: “In a variant of the Echo myth (out of grief for unrequited love the nymph Echo became a cliff from which her voice echoes), an explanation was supposed to be given for the echo by the Loreley rock [along the Rhine] as well as for the numerous accidents with river-going vessels in this place.” The German poet Heinrich Heine (1824) gave poetic familiarity and fame to Brentano’s tale of the love-spurned maiden who exacts vengeance by renouncing human love and pledging herself to the river lord. The Loreley story was subsequently treated by a number of German composers. In my view the new CPO recording makes a strong case for the Bruch opera.

A brief summary of the plot: Count Otto of a Rhenish principality has been having a dalliance with Lenore, the daughter of winemaker Hubert. But he is betrothed to Countess Bertha. In the first scene of the opera he dreamily reflects on his love for Lenore and his reluctant resolve to break off the relationship. Lenore appears, and in an emotional duet with her, Otto ends their romance.

In the very short Second Act (just one scene), the heartbroken Lenore resolves on vengeance: she will give herself as Bride to the Lord of the Rhine, in exchange for unparalleled beauty which, when observed, will break Otto’s (and men’s) heart. Fascinatingly, this short act parallels, in a striking way, the magical Wolf’s Glen scene in Karl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischutz (1821), and other unearthly  scenes in Louis Spohr’s version of Faust (original version, 1813) and Heinrich Marschner’s Hans Heiling (1833), when the dark supernatural is called upon, and, in this case, a kind of Faustian bargain is made. It’s a theme that runs through German Romanticism.

scenes in Louis Spohr’s version of Faust (original version, 1813) and Heinrich Marschner’s Hans Heiling (1833), when the dark supernatural is called upon, and, in this case, a kind of Faustian bargain is made. It’s a theme that runs through German Romanticism.

Lenore now appears at the wedding festivities of Otto and Bertha, startling all the guests, blinding them with her beauty, and causing Otto great consternation. The officiating archbishop orders her to stand trial as a sorceress, but she has committed no crime and is released.

Act four culminates in an extended a confrontation between Lenore and Otto, who has now renounced everything, his titles and estates, and his bride-to-be Bertha, to find Lenore: mesmerized, he must have her. But she is now Bride of the Rhine Lord, and rejects Otto’s entreaties. And he in turn has no other choice; in despair he jumps to his death in the river, as Lenore with her harp mounts the high rock overlooking the river as Queen of the Rhine.

Both Lenore’s “Song of the Loreley” during the wedding scene and the final scene with Otto demonstrate just what a fine musical craftsman Bruch was. Librettist Geibel did not directly use Heine’s poem for the text of the “Song of the Loreley”; rather, he penned new words for the scene at the wedding banquet:

Do you see it shining in the nuptial cup?

Do you see it shining, the red beam?

It signifies love and joy and torment!

But once it has conquered your soul,

It holds you spellbound as if with magic song;

Its anxiety lures you, and its bliss calls you

Almighty with tears of longing!

Do you see it . . . love shines

In the wine and joy and torment!

Bruch employs the haunting musical theme of Lenore’s song in the orchestral Introduction to the opera, and also in the final duet between Otto and her. And, in a sense, it is the motif of unrequited love.

Throughout, such moments illustrate Bruch’s command of very rich orchestral textures and an ability to write for the voice. He illustrates this not only in the opera’s dramatic scenes, but especially in more folk-like choral music for the winemakers and vintners. Although Bruch was no Wagnerian, there are certain pre-Lohengrin echoes in the music, or better said, the full continuation of a classical German Romantic tradition that includes Weber, Spohr, Nicolai, Marschner, and, symphonically, Mendelssohn and Schumann, and later, Brahms.

To present such a forgotten work, a superior cast is definitely needed. In the live performance from Munich’s Princeregententheater the cast is generally quite good. In the role of the love-struck Count Otto, the tenor Thomas Mohr is entirely believable, his voice both resonant and plaintiff, fully encompassing the range of emotions of his character. Mohr began his career as a baritone, and now sings a wide repertory as an heroic tenor. Soprano Michaela Kaune, the Lenore, is closely associated with the Deutsche Opera in Berlin. Possessed of an audible but controlled vibrato, her vocalism is, especially in the middle range, elegant and accomplished, notably in her scene with Otto in the first act, her aria at the wedding, and, finally, in the final scene of the work. Other roles are filled well, including Magdalena Hinterdobler as Bertha, bass Sebastian Campione as Lenore’s father, and the veteran bass baritone Jan-Hendrik Rootering as a knight minnesinger.

Read more in New English Review:

• Hollywood

• The Theory of Astrology

• Sloppy Words

Conductor Stefan Blunier leads the Munich Radio Orchestra who respond ably to his demands, and the Prague Philharmonic Choir offers stellar choral support. Indeed, Bruch’s choral work has been uniformly praised. During his lifetime, in addition to his violin concertos, his choral compositions earned him considerable renown. Now, after several listens-through of Die Loreley, my appreciation for the orchestral and choral writing only grows. Bruch invests his music with real orchestral color which enhances the drama, so that you can actually visualize the action occurring. And that is no small feat in opera productions on compact disc.

Yet, for me, that is what happens with Die Loreley in this recording. I can recommend this fine performance, with the hope that Bruch’s opera will become much better known to both opera and music lovers.

Reference notes:

Max Bruch. Die Loreley, grand romantic opera (1863), in 4 acts; Munchen Rundfunk Orchester, Stefan Lunier, cond.; Thomas Mohr, Michaela Kaune, Magdalena Hinterdobler, Jan-Hendrik Rootering; CPO set 777 005-2; 3 compact discs; 243’. Notes by Florian Heurich, cast biographies, act summaries, and a complete German-English libretto included. Co-production of CPO and BR Klassic, Bavarian Radio.

Leon Botstein, “Pfitzner and Musical Politics,” The Musical Quarterly 85(1), Spring 2001, pp. 63-75.

Andrew Desiderio, Review of compact disc of Max Bruch, String Quintet in Eb. String Quintet in A. String Octet in Bb (Nash Ensemble, Hyperion Records 68168), in Fanfare magazine, September/October 2017, vol. 41:1, pp. 182-183.

Christopher Fifield, Max Bruch: His Life and Works. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press, 2005.

«Previous Article Table of Contents Next Article»

________________________

Boyd D. Cathey was educated at the University of Virginia (MA, Thomas Jefferson Fellow) and the Universidad de Navarra, Pamplona, Spain (PhD, Richard M. Weaver Fellow). He is a former assistant to the late author, Dr. Russell Kirk, taught on the college level, and is retired State Registrar of the North Carolina State Archives. Has published widely and in various languages. He resides in North Carolina.

Follow NER on Twitter @NERIconoclast